Early in November, a major sensation erupted when it was reported that some 1,400 highly valuable works of art, most of them unseen for decades, had been discovered hidden in an apartment in Munich, Germany.

The apartment’s owner, Cornelius Gurlitt, is an eighty-year-old art dealer and recluse whose father, Hildebrand, was one of four dealers commissioned by the Nazis to sell their looted art abroad in exchange for much-needed foreign currency. Many of the works in the Gurlitt apartment appear to belong to this category of art works stolen from their owners by the Nazi regime, while others may have been consigned to the elder Gurlitt by Jews and others fleeing Hitler’s Germany while they could. A significant number are by artists, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, officially condemned by the Nazis as “degenerate.”

Many thousands of such works remain unrecovered to this day. Nor have directors of the museums where some of them ended up in the postwar years been noticeably eager to cooperate with efforts to restore them to their original owners or their heirs.

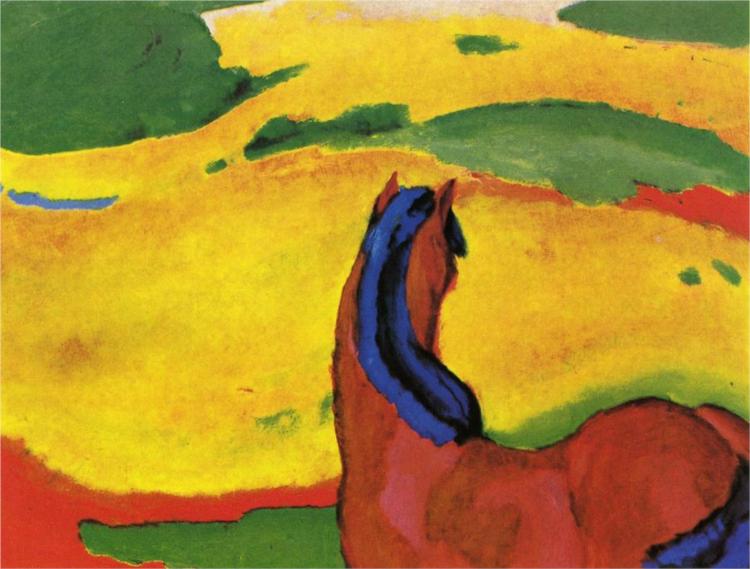

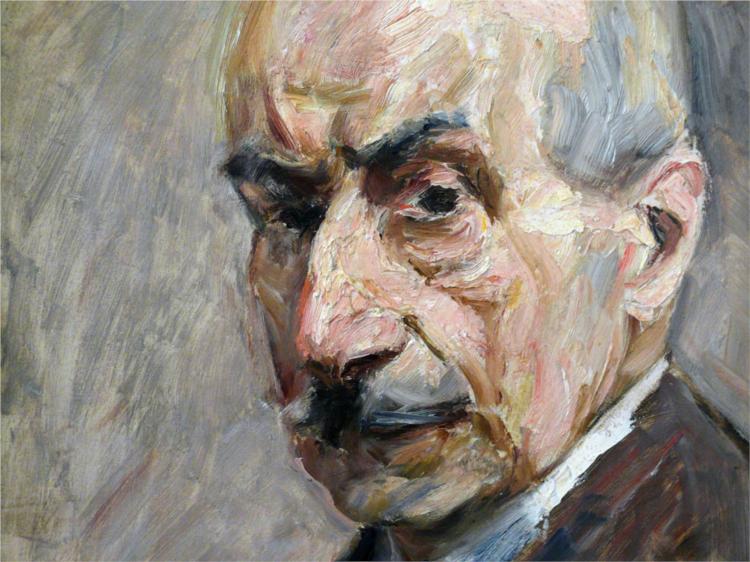

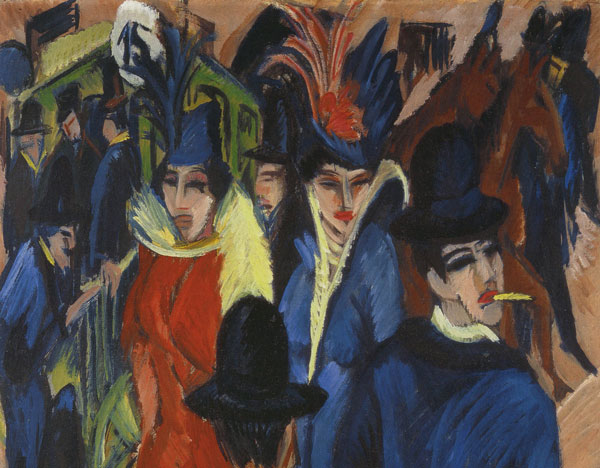

And little wonder: over time, the value of most of the works has appreciated enormously. After the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (not Jewish) committed suicide in 1938, a year after being included in the Nazis’ notorious exhibit of “Degenerate Art,” his widow was lucky to obtain several hundred dollars for one of his paintings; a few years ago, Kirchner’s Berlin Street Scene was auctioned by Sotheby’s and acquired by Ronald Lauder for $38 million. Another painting, Two Horsemen on the Beach, a particular favorite of mine by the “degenerate” Max Liebermann (Jewish, and the leading German Impressionist of his time), was virtually unsellable after the Nazis came to power. It was found among the works hidden in the Munich apartment; although Liebermann’s work has not yet come back into vogue, the painting would likely sell for at least $1 million today.

Self-portrait by Max Liebermann, the “degenerate” German-Jewish Impressionist whose Two Horsemen on the Beach was found in Cornelius Gurlitt’s apartment. Courtesy Wikipaintings.

But who are the Gurlitts? Although press stories on the Munich finds have tended to focus on the Jewish admixture in their history, the family, whose origin is German-Danish, is well known for other reasons to students of German art, music, and literature. Hildebrand’s grandfather, Louis Gurlitt, was a well-known landscape painter, and his son Cornelius—Hildebrand’s father and grandfather of the present-day Cornelius—was an architectural historian of note. Nor were these the only culturally prominent members of the clan. As for the Jewish link, which consists of Louis Gurlitt’s wife Elisabeth, that is rather attenuated by now.

Thus, to use the metric applied by the Nazi-era Nuremberg laws, the reclusive Cornelius (Elisabeth’s great-grandson) is just one-eighth Jewish, while his art-dealer father Hildebrand, who died after World War II in a car accident, was a quarter-Jew. In Nazi Germany, this was considered a blemish but did not automatically mean Auschwitz. With a little effort and good will on the part of the authorities, one could always claim a fleeting episode of marital infidelity somewhere along the line, nugatory enough to turn a quarter-Jew like the Hildebrand Gurlitt into an almost-full Aryan. Of course, in order to remain unharmed, anyone so tainted was also well advised to exercise caution and above all not to make enemies.

As it just so happens, however, Elisabeth Lewald, Hildebrand Gurlitt’s embarrassing Jewish grandmother, came from a very interesting family herself, and their story is well worth telling—less because it somehow explains or excuses Cornelius’s behavior, as is typically insinuated by the press, than because of the window it offers onto the fraught and endlessly fascinating saga of Jewish assimilation in continental Europe.

In the case at hand, the story begins in Koenigsberg, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, a Russian enclave), where Elisabeth, one of nine children, was born in 1822 to David Markus and Tzipora Asur. Markus was a well-to-do businessman and banker who, in 1831, would change the family name to Lewald. Although the exact thinking behind his choice of name remains a mystery, in general Jews looking to embellish their backgrounds in those days had to be inventive. (A branch of my family that found itself in Russia around 1810, and made influential friends there, claimed the name de Laquière and a background among the French aristocracy. Some of their descendants have persuaded themselves that the story is gospel truth.)

If changing names was easy, changing religion was more complicated. When the Lewald parents gave two of their sons permission to convert and undergo baptism so as to marry out of the faith, the sons refused unless the parents agreed to convert as well. Gradually the whole family became Christian, if without much enthusiasm.

In this, they formed a contrast to an earlier wave of German Jewish converts to Christianity around the turn of the 19th century. Some of the young Jewish-turned-Christian ladies of that former time became the leading salonnières of Berlin, and were genuinely convinced of the spiritual superiority of the Christian dispensation; their number included the daughter of the great Enlightenment figure Moses Mendelssohn. Only for later converts—like Elisabeth’s elder sister Fanny—had conversion become, as it was for Heinrich Heine, merely an “entrance ticket to European civilization.” In her six-volume autobiography, Fanny confessed that she did not really believe in any of the dogmas of Christianity.

From Berlin Street Scene 1913 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. A previously unknown painting by the “degenerate” Kirchner was discovered in the Munich apartment. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Fanny, a novelist, was by far the most famous of the Lewald children; her collected works were published in the 1860s, and some have recently been reissued in Germany. More important than the novels is her autobiography, part of which is available in English translation (The Education of Fanny Lewald, 1992). In these recollections she cites some curious (to her) Jewish customs and traditions, like shiva, that in her youth, she writes, both attracted and repelled her. She also states that she and her siblings were never told they were Jewish; instead, they learned it in the street when, clothed in their beautiful little fur coats on their way to school, they were greeted with obscenities on the part of the neighborhood riffraff.

Fanny eventually moved to Berlin, where she established a literary salon attended by some of the leading German writers of the day as well as visiting foreign luminaries like Giuseppe Garibaldi. She fell in love with a German writer—married, with five children—who eventually left his family to join her.

There were instructive differences between Fanny’s salon and its predecessors of 50 years earlier. Where Mendelssohn’s daughter Dorothea Schlegel and her friend Henriette Herz conducted mainly literary gatherings, Fanny was at least as interested, if not more so, in social and political issues. True, the salons of 1800 had also become gradually politicized, willy-nilly, as many of their non-Jewish frequenters developed strongly nationalistic and even anti-Semitic attitudes. In general, history has not been kind to the Jewish salonnières of 1800 and their high-strung followers with their darkly negative attitude toward their origins. For Rahel Varnhagen, the central figure of that wave, Jewishness was a horrible injury that would never heal; “I shall never accept,” she wrote to a male friend, “that I am a schlemiel and a Jewess.”

For her part, Fanny Lewald writes in her autobiography that even as a child, before she went to school, she was aware that her Jewishness was a disaster. But she reacted differently, becoming in later years not only an important (if not, indeed, the most important) fighter for women’s rights of her era but also a staunch champion of emancipation for the Jews.

By the time Fanny died in 1889—her sister Elisabeth would outlive her by twenty years—the Jewish origins of the Gurlitt-Lewald clan were all but forgotten. Germany had changed: women, although they hadn’t yet secured the vote, had won most other rights, and a Jew who had been properly baptized could be a minister of the crown.

Take the case of Theodor Lewald, Fanny and Elisabeth’s nephew, born in 1860. A senior civil servant, he was highly educated, of impeccable manners, and sufficiently diffident in his behavior as not to raise suspicion. He made friends everywhere, faithfully serving not only the last German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and then the Weimar Republic, but eventually even Hitler’s Third Reich. Photographs show a man of imposing stature, far more Nordic-Aryan in appearance than the “typical” Jew of Nazi race theory.

It was, in fact, owing to Theodor Lewald that Nazi Germany achieved one of its major early triumphs: the Berlin Olympic Games of 1936. This is a story with a back story. Uninterested in sports as a youngster, Lewald, who spoke English well, had become involved in the St. Louis World Fair of 1904 and counted many influential Americans among his friends. It was thus that he found himself on a German committee dealing with the international Olympics organization.

The 1916 games, which had been planned for Berlin, never materialized because of the outbreak of World War I; in the war’s aftermath, Germany was barred from participating in the 1920 and 1924 games. Only in 1928, thanks to Lewald and his networking, was Germany fully reinstated; two years later, Berlin was chosen as the site of the 1936 games. For Hitler and Goebbels, the risk in hosting an international event of this kind, with so many non-Aryans competing and possibly even winning the gold, was outweighed by the potential propaganda value of the event and the unique opportunity to enhance the Third Reich’s standing in the world.

Lewald’s prior successes had, however, created enemies. One of them was a high Nazi-party official named Hans von Tschammer und Osten who also bore the title of “Reich Sports Leader.” In April 1933, an article appeared in the Nazi paper, the Voelkische Beobachter, declaring it intolerable that someone of part-Jewish extraction should be playing a key role in the forthcoming games. But Lewald’s rivals had greatly underestimated his ability to pull strings while keeping discreetly in the background. He alerted his American connections, who in turn mobilized much of the Olympics world in a wave of protests that turned out to be effective.

This was a little surprising. Avery Brundage, the head of the American Olympics committee, was rather sympathetic toward the Nazis and not known as a friend of the Jews. But the appeal to Olympic ideals—peace, fair play, friendship among nations, and the rest—was irresistible. The Voelkische Beobachter was put on notice, and Lewald retained his position. Only after the games, when the Nazis no longer had much use for him, did the going become rougher for Theodor. Still, even during the war years he was able to obtain extra food rations and help a girlfriend escape deportation to Theresienstadt. He died in Berlin in 1947 at the ripe age of eighty-seven.

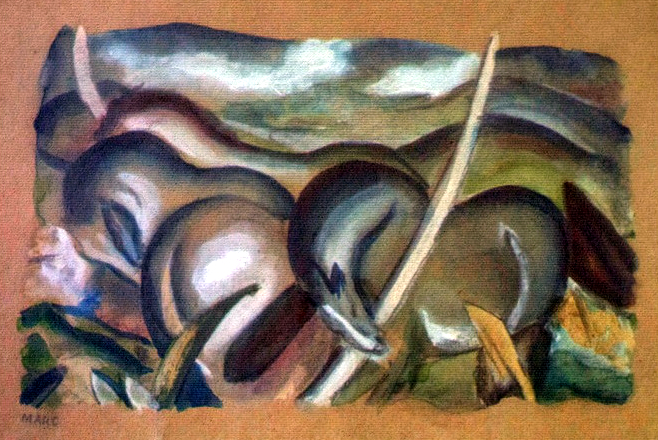

Horses in Landscape by Franz Marc. This painting was discovered in Cornelius Gurlitt’s apartment. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

By this winding path we can now return to the 1,400 artworks recovered in Munich and claimed by Cornelius Gurlitt as his family property. Although a full inventory does not yet exist, some number of them, as I mentioned early on, seem to have come from the Nazis’ notorious “Degenerate Art” exhibit of 1937. The whole concept of degenerate art was confused and controversial. Included in the 1937 exhibit were works by two of the most prominent figures of German Expressionism, August Macke and Franz Marc; neither was Jewish, and both happened to be war heroes, having been killed in battle in World War I.

Another early Expressionist included in the exhibit was Emil Nolde, a German nationalist and an early Nazi whose work had been supported by Goebbels and others. But Hitler, who abominated all forms of modernism in art, overruled them. After the war, Nolde received the Grand Order of Merit from the West German government. Two years ago, Sotheby’s sold his Flower Garden for $3.2 million. As for specifically Jewish painters, the most prominent at the time was Liebermann; but he, too, should never have been included in the exhibit since he never produced abstract paintings.

In addition to products of German art, Jewish and otherwise, the Gurlitt collection also boasts works by such eminent non-German modernists as Picasso and Chagall, probably bought by German collectors before 1933 or seized in occupied France, as well as perfectly respectable items of older vintage by the likes of Canaletto and Rodin. It is said that eventually some 600 paintings in the Gurlitt collection will be made available for viewing on the Internet.

What will eventually happen to these pictures? Even if the original owners or their heirs or representatives can be located, it is quite possible that few will be able to prove a legally valid claim. So Cornelius Gurlitt might keep at least some of his treasure after all. What will it be worth? The highest price ever registered at auction for a single work, $268 million, was paid by the government of Qatar in 2011 for Cézanne’s Card Players. It is unlikely that any picture in the Gurlitt collection would command a similar price—but there may be no end of surprises in this saga.

Indeed, the final such surprise may belong posthumously to Fanny Lewald, who spent the last years of her life in a hotel in Dresden. Since 1993, a street in that city, Fanny Lewaldstrasse, has been named for her. Its original name was nothing less than Friedrich Auguststrasse, honoring the last emperor of Saxony. Under the Communists, it became Wilhelm Pieckstrasse, after the president of the former East Germany.

But if things were different in 1889, when Fanny died, they are more different now. Even in her wildest dreams she could not have imagined that one day not only would women in her homeland have equal rights but a woman would be serving as prime minister. Perhaps most surprising to her of all, a day would come when a Jewish grandmother in the family closet would no longer be regarded as a shameful embarrassment but as a mitigating circumstance, an excuse, even an asset.

__________

Walter Laqueur is the author of, among other books, Weimar, A History of Terrorism, Fascism: Past, Present, Future, and The Dream that Failed: Reflections on the Soviet Union. His newest book, Optimism in Politics and Other Essays, is due out from Transaction in January.