From the mid-19th century to the present, Russian writers and thinkers have tirelessly debated human life’s essential nature. Is life defined by the countless ordinary events or the few extraordinary ones? Should one focus on the forgettable prosaic moments or the memorable dramatic ones that make a good story? Which sentiment comes closer to the truth: the proverbial curse, “May you live in interesting times!” or Wordsworth’s enthusiasm that “to be young” during the French Revolution “was very heaven”?

Russia’s revolutionaries typically answered these questions one way, the greatest writers—especially Tolstoy and Chekhov—the other. For Isaac Babel, arguably Russia’s greatest prose writer in the 20th century’s first decades, they posed a dilemma. On the one hand, the romantic revolutionary ethos that had conquered the intelligentsia attracted him. On the other, Tolstoy’s antithetical ideas, which stressed the virtues found in life’s ordinary moments, could not be gainsaid. His values came much closer to the Jewish tradition in which Babel grew up.

In Tolstoy’s view, the more dramatic a life is, the worse it is. The eponymous heroine of Anna Karenina excites the reader’s interest with her melodramatic love affair and death, but the incidents illustrating a meaningful life lie outside the main plot lines. They belong not to Anna, but to the novel’s most prosaic central character, Dolly. If by a novel’s hero, we mean the character whose values are closest to the author’s, then Dolly is the true hero of Anna Karenina. She takes care of her children, helps those around her in small ways, and strikes everyone as entirely uninteresting, or in the words of her appalling husband Stiva, as “merely a good mother.”

For Tolstoy, that “merely” is entirely wrongheaded. What Tolstoy calls “women’s work” sustains the world, and the efforts of good mothers, which people usually take for granted, are far more important than the usual labors of men. Tolstoy therefore gives Dolly the scene that illustrates what makes a truly meaningful life. To save money, she brings her children to the countryside where Stiva was supposed to have arranged the house suitably, but he hasn’t. Having jury-rigged a few solutions, Dolly at last experiences a few precious moments when

the children were . . . repaying her in small joys for her sufferings. These joys were so small that they passed unnoticed, like gold in sand, and at bad moments she could see nothing but pain, nothing but sand; but there were good moments too when she saw nothing but joy, nothing but gold.

“Gold in sand”: far from dramatic, life’s key moments are so small that they pass almost unnoticed. In War and Peace, Tolstoy makes a similar point about the life of nations: History is shaped less by the dramatic actions of great men than by the sum total of countless prosaic actions undertaken by ordinary people.

Revolutionaries, and the intelligentsia generally, regarded this stress on the prosaic as profoundly mistaken. They disparaged lives focused on the prosaic as vulgar and bourgeois. The women they celebrated became terrorists, like Sophia Perovskaya, who directed the operation that succeeded in assassinating Tsar Alexander II, or Hesya Helfman, a young Jewish woman who helped her.

For the radicals, those immersed in the everyday miss life’s essence, which is lived at times of maximal intensity. The poet Alexander Blok (1880-1921), who celebrated the Revolution precisely because it disrupted tradition and daily life, discovered in violence an antidote to “the boredom, the triviality” of ordinary life. For him, the goal of terror mattered less than “the roar.” The famous terrorist Boris Savinkov also wrote novels evoking the romance and thrill of killing, thereby combining pre-Revolutionary Russia’s two most prestigious occupations. “What would I do if I were not involved in terror?,” asks the hero of his novel Pale Horse. “I don’t want to live a peaceful life. . . . What’s my life . . . without the joyful awareness that laws are not for me?”

Ideology did not concern Savinkov, who would ply his murderous craft for just about anyone. We may notice in him and others a progression to unrestrained violence for its own sake. First, the goal was Communism, and revolution merely the means. Then revolution became the goal in itself and terror was the means. Then terror became an end in itself and was revered as an art form. Pure violence, irrespective of purpose, became the goal. The presently influential cultural theorist Slavoj Žižek embraced and neatly summed up this way of thinking: “In every authentic revolutionary explosion, there is an element of ‘pure’ violence,” he explained. “An authentic political revolution cannot be measured by [the] extent [to which] life got better for the majority afterward—it is a goal in itself; . . . one should directly admit revolutionary violence as a liberating end-in-itself.”

I. The Smell of Life and Death

Jews disagreed about revolution. On the one hand, Jews made up a disproportionately large part of the revolutionary movement. At least a third of the original Bolshevik leaders were Jews, as were about half of the anarchists. On the other hand, traditional Jews abhorred these renegades from the faith, whose violent actions were bound to be blamed on the Jewish people as a whole. Indeed, Jewish revolutionaries often conducted terror attacks in order to provoke anti-Jewish pogroms and thereby radicalize the population. As a Moscow rabbi quipped, “it’s the Trotskys who make the revolutions, and the Bronsteins who pay the price.” (Bronstein was Jewish Trotsky’s original name.) Some families sat shiva when a young man or woman joined the revolutionaries.

Brought up with a traditional Jewish education, but fascinated by the Russian intelligentsia’s cult of revolutionary violence, Isaac Emmanuilovich Babel (1894-1940) experienced the attraction to both radicals and traditionalists. In Babel, Trotsky, revolution, violence, and “the cult of dynamite” competed with Tolstoy, rabbis, mothers, and reverence for Jewish tradition. This combination of antithetical attractions still makes his stories especially exciting.

The Russian question about whether life’s essence lies in the prosaic or the dramatic obsessed Babel. To answer it, he incurred enormous risks. Curiosity consumed him, as his acquaintance, the Jewish writer Nadezhda Mandelstam observed, and he was willing to do almost anything to follow it. According to her, everything about Babel—“the way he held his head, his mouth, his chin, and particularly his eyes”—expressed “the unbridled curiosity with which he scrutinized life and people.”

In one autobiographical story, the young Babel learns to view his surroundings “in a special way, . . . and I was quite certain I could see in them what was most important, mysterious, what we grown-ups call the essence of things.” He writes that his grandmother told him, “You must know everything,” and with this demand shaped “my destiny, and her solemn contract presses firmly—and forever more—upon my weak shoulders.” In Russia, the way to “know everything” was to be a great writer and compete with Tolstoy.

Even at times of greatest danger, Babel tempted fate to learn more about life and death. At a time when any contact with foreigners amounted to a death sentence, Babel chose to live in a building where foreigners stayed. During Stalin’s great purges he conducted a love affair with the wife of the head of the secret police, the NKVD. (The NKVD did arrest and execute him, but not for that reason; exactly why is unclear, as it was for millions of others.) Indeed, Nadezhda Mandelstam recalled, Babel loved to hang out with NKVD agents. Her husband, the poet Osip Mandelstam, once asked Babel whether he was motivated by “a desire to see what it was like in the exclusive store where the merchandise was death.” Babel replied: “I just want to have a whiff and see what it smells like.” Odors, conveying what words cannot, figure prominently in his stories.

II. Cossacks and Jews

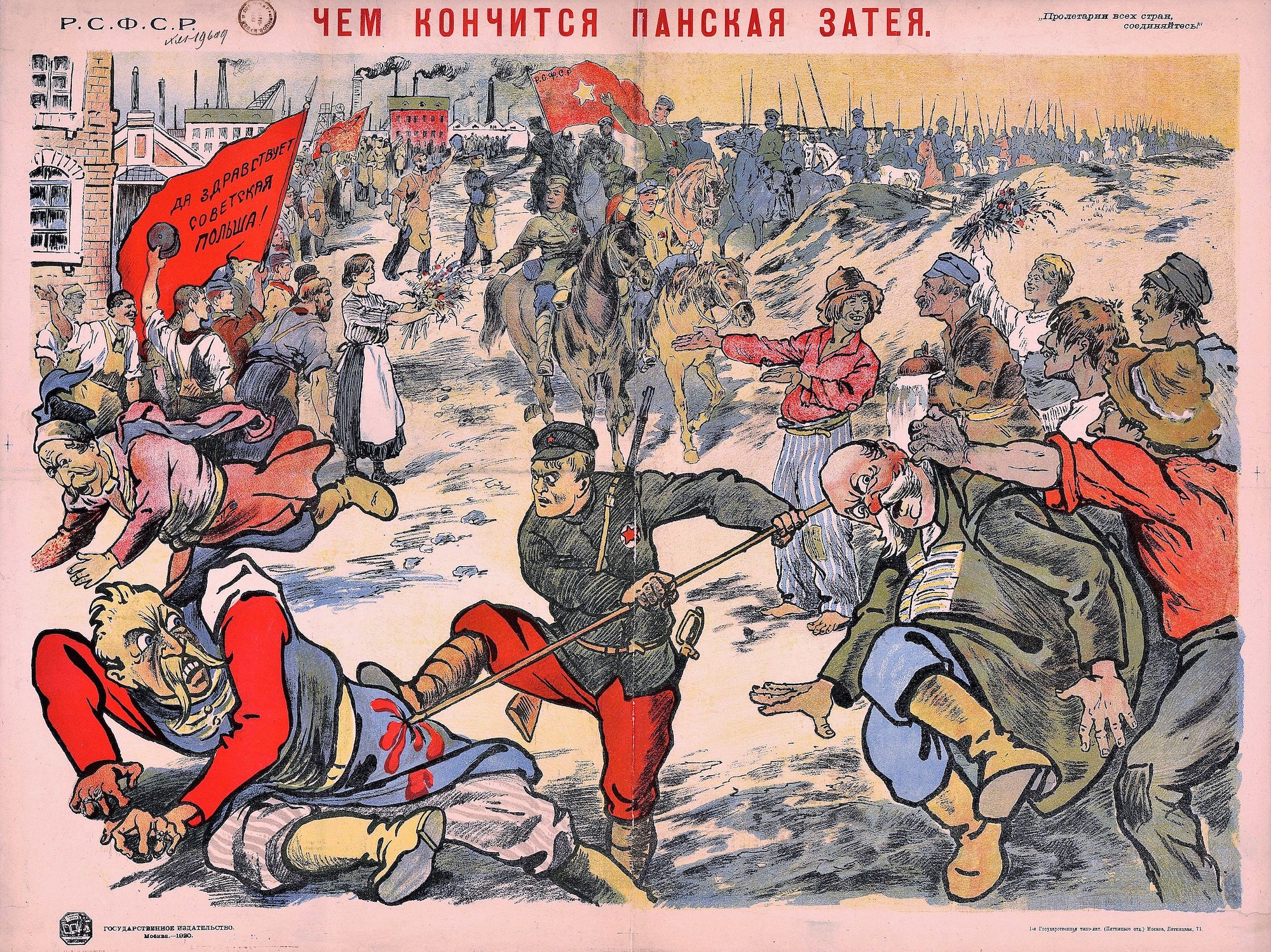

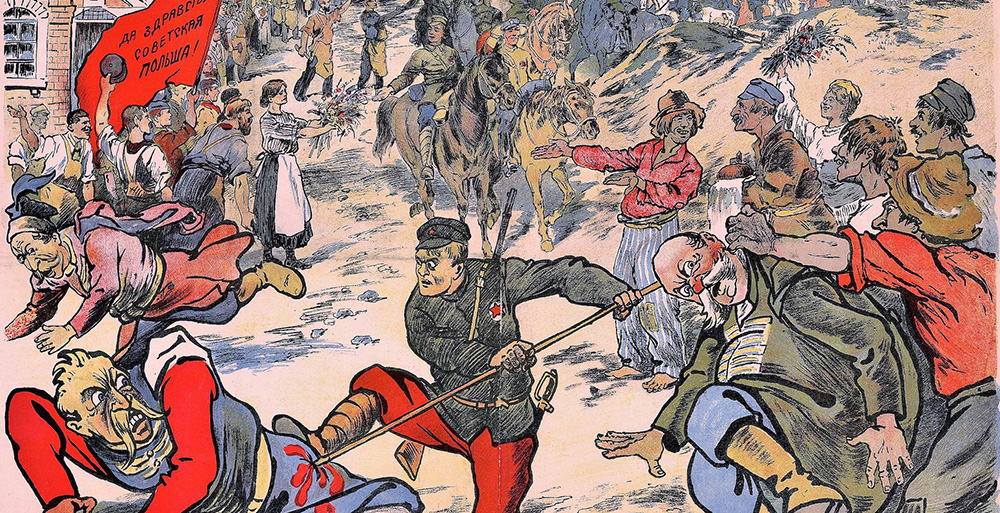

After serving as a soldier on the Romanian front of the First World War in 1917, Babel’s curiosity prompted him to fight in the Russian civil war (1918-1920), which pitted the new Soviet regime (the “Reds”) against a heterogenous alliance of their opponents (the “Whites”). Then he became a war correspondent with the Bolshevik armies that invaded Poland with the goal of bringing the Revolution to Europe and eventually the world. His regiment consisted mainly of Cossacks, militarized horsemen from the steppes who celebrated a violent freedom and were famous for their anti-Semitism. Babel assumed the very Russian name of Kiril Vasilievich Lyutov (Lyutov means “ferocious”) and concealed his identity. Jews comprised a large proportion of the population in the areas invaded, and Babel felt alternately repelled by and attracted to them. “Talking to the Jews,” he wrote in his diary, “I feel kin to them. They think I’m Russian, and my soul is laid bare.” Babel transformed the experiences recorded in the diary into his cycle of stories known in English as Red Cavalry. The diary’s raw observations about gratuitous and terrifying violence inspired a work that create a peculiar, grotesque beauty saturated with blood and redolent of unsolvable mysteries about good and evil. One of Dostoevsky’s characters asks if it is possible to find beauty in ugliness (“Sodom”), and Babel’s stories demonstrate that it is.

“I am an outsider,” Babel wrote in his diary, a Russian among Jews and a secret Jew among Cossacks. Cossacks cultivated an ethos of violent masculinity that seemed diametrically opposed to Jewish culture. “What sort of person is our Cossack?,” Babel asked himself. “Many-layered: looting, reckless daring, revolutionary spirit, bestial cruelty. We [as a Bolshevik regiment] are the vanguard, but of what?” Having suffered atrocities committed by Polish forces, some local Jews welcomed the Bolsheviks as liberators and avengers, only to receive similar treatment from them. “The hatred is the same, the Cossacks just the same, the cruelty the same, it’s nonsense to think one army is different from another. . . . There is no salvation. Everyone destroys them.” Babel recorded how “our men were looting last night, tossed out the Torah scrolls in the synagogue and took the velvet covers for saddlecloths.”

In the story “Berestechko” (named for the shtetl where it takes place), Lyutov, quartered with a red-haired Jewish woman “who smelled of the grief of widowhood,” witnesses how the Cossack soldier Kudrya gracefully, almost ritually, slaughters a Jewish inhabitant. He “got hold of his head and tucked it under his arms. The Jew quieted down and spread his legs. With his right hand Kudrya drew his dagger and carefully cut the old man’s throat, without splashing himself.” The reader wonders whether this scene’s details—the placement of the victim’s limbs and body, the precision of the blade, Kudrya’s slitting of the Jew’s throat—is meant to seem like a cruel inversion of the Jews’ ritual slaughter of kosher animals.

Everyone murders and plunders Jews, Babel laments. The combined depredations of Poles, Whites, and Reds lead Babel to wonder whether the Jewish people have any future at all: “Can it be that ours is the century in which they perish?,” he asks in the diary. In the story “Zamoste,” one character remarks: “The Yid stands guilty before everybody . . . After the war, only the smallest number of them will be left.”

Some Jews ask Babel whether under the Bolsheviks they will still be able to trade in goods. Babel knows they will not but tells them otherwise to comfort them. He reports in his diary that he knowingly deceived them—he calls this practice “my usual system”—by painting a glorious picture of the future: “They listen with delight and disbelief. I think . . . everything and everyone will be turned upside down and inside out for the umpteenth time, and I feel sorry for them.”

III. Violence as Experiment

All this violence was not a byproduct of the Revolution but an essential component, as Lenin understood with chilling clarity. While other revolutionary movements, in Russia and elsewhere, sought to create loosely organized mass movements, he fashioned the Bolsheviks into a small, tightly disciplined party ready to commit any violence at the leader’s command. Constituting a tiny minority of the empire’s population, the Bolsheviks relied entirely on terror, the more brutal the better, to retain power. Lenin lost his temper at anyone who refrained from killing, looting, and hostage-taking, and in order after order he demanded his followers be “merciless.” (The word became the highest praise in Soviet rhetoric.) Feeling that Russians were too soft-hearted and inefficient, he relied as much as possible on other ethnic groups. It was therefore obvious to Babel that the Cossack’s brutality was “simply a means to an end, . . . one the party does not disdain.”

Babel tried to look on everything he witnessed with anthropological detachment. According to Russian tradition, writers were regarded as discoverers of ultimate truths about human nature accessible in no other ways, and Babel took this tradition to an extreme. Witnessing endless killing, he was doing research, trying to “know everything,” to become a great writer and to discover life’s essence.

It turned out he was not the only would-be anthropologist. The most memorable story in Red Cavalry, “The Life and Adventures of Matthew Pavlichenko,” concerns a Bolshevik officer returning to the estate where his master, Nikitinsky, had forced himself on his wife. Readers expect a revenge story, but it turns out that revenge is only secondary. Sensing his absolute power, Pavlichenko uses it above all to understand the depths of the human soul. As a writer, Babel witnesses extreme horror to probe the soul, but Pavlichenko goes one step further and conducts experiments himself. Instead of simply shooting his former master, as Nikitinsky anticipates, Pavlichenko experiments on him by killing him slowly.

I trampled my master Nikitinsky. I trampled on him for an hour or more than an hour, and in that time, I got to know life in full. Shooting—I’ll put it this way—only gets rid of a person, shooting is an act of mercy for him and for you it’s wicked easy. Shooting won’t get at the soul, to where it is in a person, and how it shows itself. But, some of the times, I don’t spare myself, some of the times, I trample an enemy for an hour or more than an hour, seeing as I wish to get to know life, this life that we live.

Pavlichenko doesn’t spare himself here: a sort of social scientist, he undertakes the difficult process of acquiring precious knowledge, knowledge about the naked soul, with all protective coverings removed. Far from self-serving, this explanation of torture is entirely sincere, and it is all the more horrifying for that reason.

The Nazi experience gave rise to Holocaust literature, which showed how the extreme conditions of the death camps revealed unsuspected truths about human life. Soviet literature about the slave labor camps known as “the Gulag” did much the same thing. Anyone who has read Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation or Varlam Shalamov’s stories about Kolyma, where prisoners worked at 60 degrees below zero in inadequate clothing and with insufficient calories to sustain life, recognizes how well Pavlichenko’s curiosity would have been satisfied by conditions to come. In this sense, Babel’s story is prophetic.

IV. Gedali’s Wisdom

Several stories in Red Cavalry convey the opposite perspective. Instead of riveting the reader with violence, they focus on the beauty of daily life’s traditional forms. Like Tolstoy’s novels, they celebrate the prosaic. In these tales, Babel breathes the delicious air of Jewish rituals and celebrates the arrival of the Sabbath. “Do you remember Zhitomir, Vasily?” the book’s final story begins. “Do you remember the River Teterev, Vasily, and that night when the Sabbath, the young Sabbath, crept along the sunset, crushing the stars beneath her little red heel?”

Revealing his Jewish identity for a moment, away from the soldiers, Lyutov prays in the synagogue. As he joins in practices performed by countless Jews over centuries, he feels closer to life’s essence and to the memories of childhood that shape his core self. “On Sabbath eves I am afflicted by the dense melancholy of memories,” the story “Gedali” begins. “The old woman in her lace cap would trace fortunes with gnarled fingers over the Sabbath candles and sob sweetly. On such evenings my child’s heart pitched and tossed like a little ship upon the enchanted waves. Oh, the rotted Talmuds of my childhood!” Here, as elsewhere in the stories, “rotted” but cherished objects transmit the odors and spirit of precious daily rituals. Surely it is here, not in Cossack violence, that true life is to be found!

The old Jew Gedali speaks the opening words of the story “The Rebbe”:

All is mortal. Only the mother is destined for life immortal. And when the mother is not among the living, she leaves behind a memory none yet has dared to defile. The memory of the mother nourishes us in compassion like the ocean, a boundless ocean that feeds rivers dissecting the universe.

“The dying evening” envelops Gedali “with the rose-tinted haze of its sadness” as he explains that Ḥasidism, though its “doors and windows have been smashed, . . . is immortal, like the soul of the mother. . . . With oozing sockets Ḥasidism still stands at the crossroads of the raging winds of history.” Accompanying Gedali to the Rebbe Motale, Lyutov senses the beauty and incomparable value of a rich and probably doomed tradition. “A shy star was kindled in the orange strife of the sunset,” he explains, “and peace, Sabbath peace, rested upon the crooked roofs on the Zhitomir ghetto.”

V. The Hidden Gospel

How precious is the prosaic, the tradition, and the ordinary people who sustain it! Revolution and all movements that romanticize extreme situations look instead to the thrill of great moments and the dramatic overthrow of the burdensome past. The Russian experience shows how dangerous disparagement of the prosaic can be. Babel understood from the regime’s first day that danger, not only for Jews but for other traditions as well.

After all, not only Jews appreciate peace and the prosaic. Among the Catholics, Lyutov encounters Pan Apolek, a painter with the ability to perceive the sacred in the most ordinary of people and the most quotidian of rituals. With the same lyric voice that praises Ḥasidism and the immortal mother, Lyutov writes: “The wise and wonderful life of Pan Apolek went to my head like an old wine. In Novograd-Volynsk, among the twisted ruins of that swiftly crushed town, fate threw at my feet a gospel hidden from the world.” The beauty of Apolek’s heretical, hidden “gospel” overcomes Lyutov’s misanthropic resentments and for a moment he renounces “the sweet spite of daydreams, my bitter scorn for the curs and swine of mankind, the fire of silent and intoxicating revenge.” Instead, “surrounded by the simple-hearted glow of halos, I then made my vow to follow Pan Apolek’s example.”

Pan Apolek outrages the local priest by depicting biblical figures with the faces of his neighbors, ordinary men and women known to be not especially virtuous. Gathered to see the church frescoes he has been commissioned to paint, dignitaries are shocked to “recognize Yanek, the lame convert, in Saint Paul, and in Mary Magdalene a Jewish girl named Elka, daughter of unknown parents and mother of numerous stray children.” The priest orders the sacrilegious frescoes covered and the vicar of Dubno complains that Pan Apolek has made saints of sinners. But limping Vitold, who fences stolen goods, defends Apolek: “Isn’t there more verity in Pan Apolek’s pictures, which suit our pride, than in your words, full of reproach and lordly wrath?” And don’t people understand the Gospel best when they locate the sacred within the reach of everyone?

Pan Apolek also repeats apocryphal tales about Jesus as a Jew among ordinary Jews. In one, a young Jewish bride named Deborah, thirsting for her husband and yet terrified of him, disgraces herself by vomiting. Shame falls on the virgin. But Jesus “placed upon himself the groom’s wedding clothes and, full of compassion, joined with Deborah, who lay in her vomit.” She goes forth to the guests in triumph. “And only Jesus stood to the side. A deathly perspiration had broken out on his body, the bee of sorrow had stung his heart. No one noticed him as he departed from the banquet hall and made his way to the wilderness east of Judea, where John awaited him.” Jesus, too, had a sin to be forgiven; or can what is called sin sometimes be sacred?

VI. Mothers

If life’s essence lies not in violence or extreme situations, but in the gradual accumulation of ordinary family life, then, Babel’s stories suggest, it resides among women, especially among the mothers who make life possible and feed not just the body but also the soul. Women nourish, men destroy; men eviscerate, women give birth. Tired of the soft beauty of the prosaic, men cultivate the terrible beauty of hatred. These oppositions structure Red Cavalry.

Women, of course, do not figure among the soldiers, but from the first story they define the civilian world the soldiers invade. And their values are present symbolically elsewhere—for example, in Lyutov’s coachman Grishchuk, who can appreciate all that women prize. In “The Death of Dolgushov,” Grishchuk and Lyutov see a wounded man whose guts are hanging out. “Why do women bother?” Grishchuk asks mournfully. “What’s the point of matchmaking and marriages and kin dancing at weddings? . . . Makes me laugh. . . . Makes me laugh why women bother.”

The dying man asks Babel to shoot him so the Poles won’t find him and “play their dirty tricks” on him, but Lyutov, who cannot kill anyone, walks away. His cowardice costs him his friend Afonka Bida, who does the job for him. Enraged at the cruelty of Lyutov’s refusal, he almost kills him, too. As the story ends, Lyutov laments to Grishchuk that he has lost his friend. The coachman offers consolation with the most prosaic of gifts. “Grishchuk took a shriveled apple from under his driver’s seat. ‘Eat,’ he said to me, ‘Please, eat.’”

Grishchuk’s pacific values give Lyutov pause, because he has longed to overcome his stereotypically Jewish and effeminate abhorrence of violence. “My First Goose,” one of Babel’s most famous stories, recounts how Lyutov, who has just arrived in the Cossack regiment and is mocked for his intellectual demeanor, earns respect by brutally killing a goose and rudely demanding a woman cook it. “The lad will do,” one of the soldiers concludes, and they all listen to Lyutov read Lenin’s recent speech. Lyutov’s violence and enthusiasm for Lenin’s muscular prose win the wary Cossacks over. They all fall asleep, “all six of us, warming one another, our legs intermingled, beneath a tattered roof that let in the stars.” The story concludes: “I had dreams and saw women in my dreams—and only my heart, crimsoned with murder, squeaked and flowed.”

Raw sexuality appears in these tales whenever Lyutov passes a test of masculinity.

In another story, Lyutov befriends a man who “would talk to me of women with such thoroughness that I was embarrassed and delighted to listen. This, I think, was because we were both delighted by the same passions. Both of us looked on the world as a meadow in May, a meadow traversed by women and horses.”

VII. Messiahs Old and New

In one of the shocking paradoxes in which Babel delights, Jesus, with his infinite compassion, also figures as a symbol of Jewish values in these stories.

Lyutov, for instance, discovers an arresting image of impending violence when a group of soldiers come across a church statue. It depicts a fleeing, bearded figure, whose expression of horror makes the onlookers cry out. Evidently just about to be overtaken, “his hand was bent to ward off the impending blow, and the blood flowed carmine from that hand.” The figure is “Jesus Christ, the most extraordinary image of God I had ever seen in my life.” This Jesus, trying to escape from hatred and violence, strikes Lyutov as “a curly-headed little Yid with a ragged beard and a low, wrinkled forehead. His sunken cheeks were crimson-hued, thin red brows arched over his eyes closed in agony.” Since Jesus is destined to be crucified, the story seems to ask, are the Jews also about to face ultimate punishment, to be killed for others’ sins?

To Christians, Jesus, the lamb of God, represents an alternative to the violent masculinity embodied, for Babel, in the Cossacks. And for all his efforts to become less like Jesus and more like the cavalrymen, Lyutov never overcomes his Jewish reluctance to kill. In “After the Battle,” one of the soldiers, Ivan Akinfiev, reveals that Lyutov has gone into battle with his gun unloaded, so as not to kill anybody. “You must be either insane or a Molokan” (a member of a pacifist Christian sect), Akinfiev shouts. “I got a law about Molokans,” he asserts. “You can get rid of them, they’re God worshippers.” As the story ends, Lyutov remembers, “evening flew skyward like a flock of birds, and darkness covered me in its water wreath. I was exhausted and . . . I kept on, imploring fate to grant me the simplest of abilities—the ability to kill a human being.”

Stories about Jews and violence frame Red Cavalry. In the cycle’s opening tale, “Crossing the Zbruch” (the river the separates Ukraine from Poland), the narrator, whom we still do not know is Jewish, conceals his identity from the Jewish family with whom he is billeted. Disgusted at the squalor in which these Jews live, he demands they clean up their hut. At last a pregnant woman gives him “a featherbed that had been disemboweled” to sleep on, and he lies down next to another, “already sleeping Jew.” He wakes up from a dream about a man shot in the eyes when “the pregnant woman was groping my face with her fingers.” She reveals that they have played a terrible joke on him: the Jew next to him, her father, is not sleeping, but dead, with “his throat torn out, his face cleft in two.”

The woman describes how the Poles murdered her father. He begged them to kill him outside so his daughter wouldn’t witness the horrible scene, “but they did as they saw fit. He met his end in this room and was thinking of me. And now I should wish to know,” the daughter says suddenly, “I wish to know where in the whole world you could find another father like my father.” Violent men like the ones Lyutov has joined murder family and desecrate the prosaic.

In the cycle’s final story, “The Rebbe’s Son,” Lyutov encounters the young man of the title, whom he had met earlier in his adventures. Ilya, the son of the same rabbi whom Gedali took Lyutov to visit—“a youth with the face of Spinoza, the mighty brow of Spinoza, [and] the wan face of a nun”—was then disrespectfully smoking and shivering “like an escaped man caught and returned to his cell.” Since Ilya is the Russian form of Elijah, who is supposed to precede the coming of the messiah, we may be inclined to detect irony in the name. But it turns out that the young man has turned from the traditions of his father to serve a different messiah, Lenin—a betrayal that entails being cursed by pious Jews like his family.

As the cycle closes, Lyutov encounters Ilya as he is dying, shot in battle after he has answered the summons of his new faith and become a Bolshevik commander. When the narrator investigates the dying man’s trunk, he discovers “dumped together” relics of the two cultures—Judaism and Bolshevism, tradition and destruction, intellectuality and weaponry—that have captivated Ilya:

Portraits of Lenin and Maimonides lay side by side. The knotted iron of Lenin’s skull and the faded silk of Maimonides’ portraits. A lock of woman’s hair lay in a booklet of the resolutions of the party’s Sixth Congress, and the margins of Communist leaflets were crowded with crooked lines of ancient Hebrew verse. They fell upon me in a mean and dreary rain—pages of the Song of Songs and revolver cartridges.

Lyutov reminds Ilya of how they met months ago, before he had joined the party. Ilya replies that he had already joined the party, but concealed it “because I couldn’t leave my mother behind.” But at last, when the Bolsheviks summoned him, he did. “In a revolution,” he explains, “a mother is an incident.”

Or does it just seem that way? Hearing Ilya speak thoughts he himself has entertained, what is Lyutov’s reaction? He seems to ask whether the reverse is true, that the prosaic and everything symbolized by “mothers” matters more than Revolution? He may recall Gedali’s faith that for Jews—and all who value tradition and life’s prosaic rituals—“only the mother is destined for life immortal.” In the very first story in Red Cavalry, Lyutov, a Bolshevik posing as a Gentile, bullies a Jewish woman and her family. But it is with Ilya’s death that Babel chooses to close the cycle. Violent men leave a legacy of death, while the mother “leaves behind a memory none has dared to defile. The memory of the mother nourishes us in a compassion like the ocean, a boundless ocean that feeds rivers dissecting the universe.”

More about: Arts & Culture, Bolshevism, Communism, History & Ideas, Isaac Babel, Literature, Russian Jewry