“Severe, Jerusalem-generated mental problems.” Such, as characterized by the British Journal of Psychiatry, is the pathological derangement known as Jerusalem Syndrome. The madness is generally attributed to the city’s intoxicating spiritual powers, recognized over the centuries to inspire wild prophecies, orotund pronouncements, and utopian fantasies sometimes accompanied by predictions of imminent apocalypse.

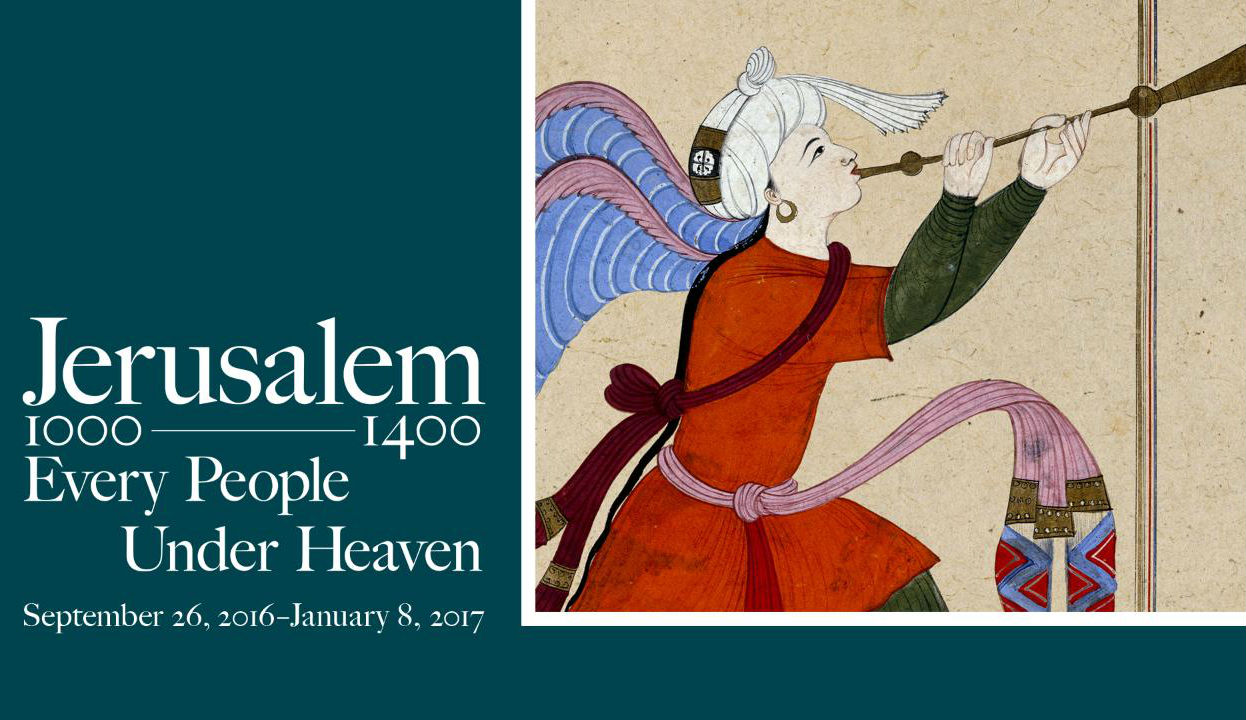

If you happened to visit New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in recent months, you might have detected a particular, very contemporary version of the syndrome lurking in the background of Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven, a sumptuous and ecstatically received exhibition that closed on January 8 after a three-month run. Or maybe not, if the contagion has spread as widely as now seems—since most visitors, and for that matter most reviewers and critics, were thoroughly seduced by the ravishingly beautiful items on display. These included illuminated manuscripts in exotic calligraphy like the ancient Hebrew script of the Samaritans; caches of gold and jewelry that until recently had been hidden in jars or lay sunk off the Caesarea coast; gilt pages of Qurans; handwritten letters by the medieval Jewish luminaries Moses Maimonides and Judah Halevi; intricately carved capitals from the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth; and much more.

I hope to unveil the syndrome’s symptoms, mostly unnoticed, that were enmeshed in these displays, and that also appear to have infected the show’s organizers in arranging and presenting them. In a lavishly produced catalog, the exhibition’s two curators, Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb, enthusiastically describe the attraction—they call it, approvingly, a “fever” and a “profound obsession”—exercised by medieval Jerusalem on the minds and spirits of “every people under heaven.” Elaborating further in the catalog’s foreword, Thomas P. Campbell, the director of the Met, finds medieval Jerusalem’s mixture of “multiple competitive and complementary religious traditions” to be so suggestive, with their “harmonious and dissonant voices passing in the narrow streets of a city not much larger than midtown Manhattan,” as to inspire the wish that the same mixture might “find resonance in today’s New York, with its similarly rich mosaic of heritages living side by side,” thereby serving as a corrective to our own fractious circumstances—a model to emulate.

The thesis is so reasonable, the exhortation so appealing, the hope so glossily enchanting, that the entire enterprise, along with its larger cultural and political implications, begs to be examined with cooler, less feverish eyes.

I. A City of Enterprise and Delight

As might be expected from an art museum where artifacts are selected not primarily to illustrate salient historical points but for their aesthetic or visceral power, the initial impression made by the Met’s Jerusalem 1000-1400 exhibition was indeed forceful. The first gallery—“The Pulse of Trade and Tourism”—pictured a city commonly associated with pious devotion and religious belief as, instead, a center of effervescent enterprise and sensual delight. This “crossroads of the known world” was, the curators write, an “economic hub, fed by the influx of religious pilgrims, adventurers, and merchants of many faiths, coming from Italy, India, and lands in-between.” In the wall text, a medieval Milanese visitor to Jerusalem exclaims: “What delighted me most was the sight of the bazaars—long, vaulted streets extending as far as the eye can reach.” Other medieval accounts cite the “hubbub” of streets where goldsmiths worked side by side with chicken vendors and merchants hawking spices, vegetables, and textiles.

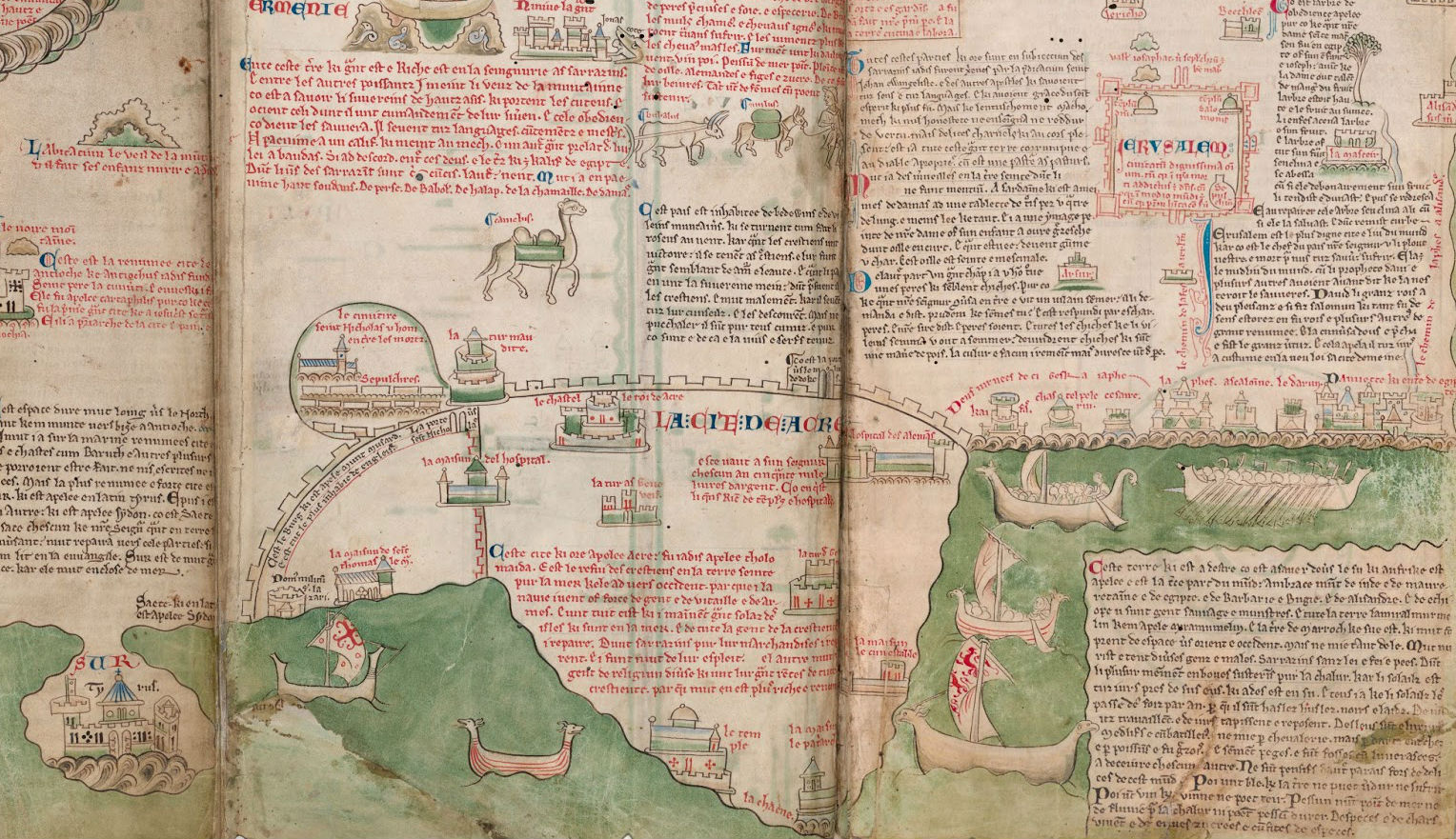

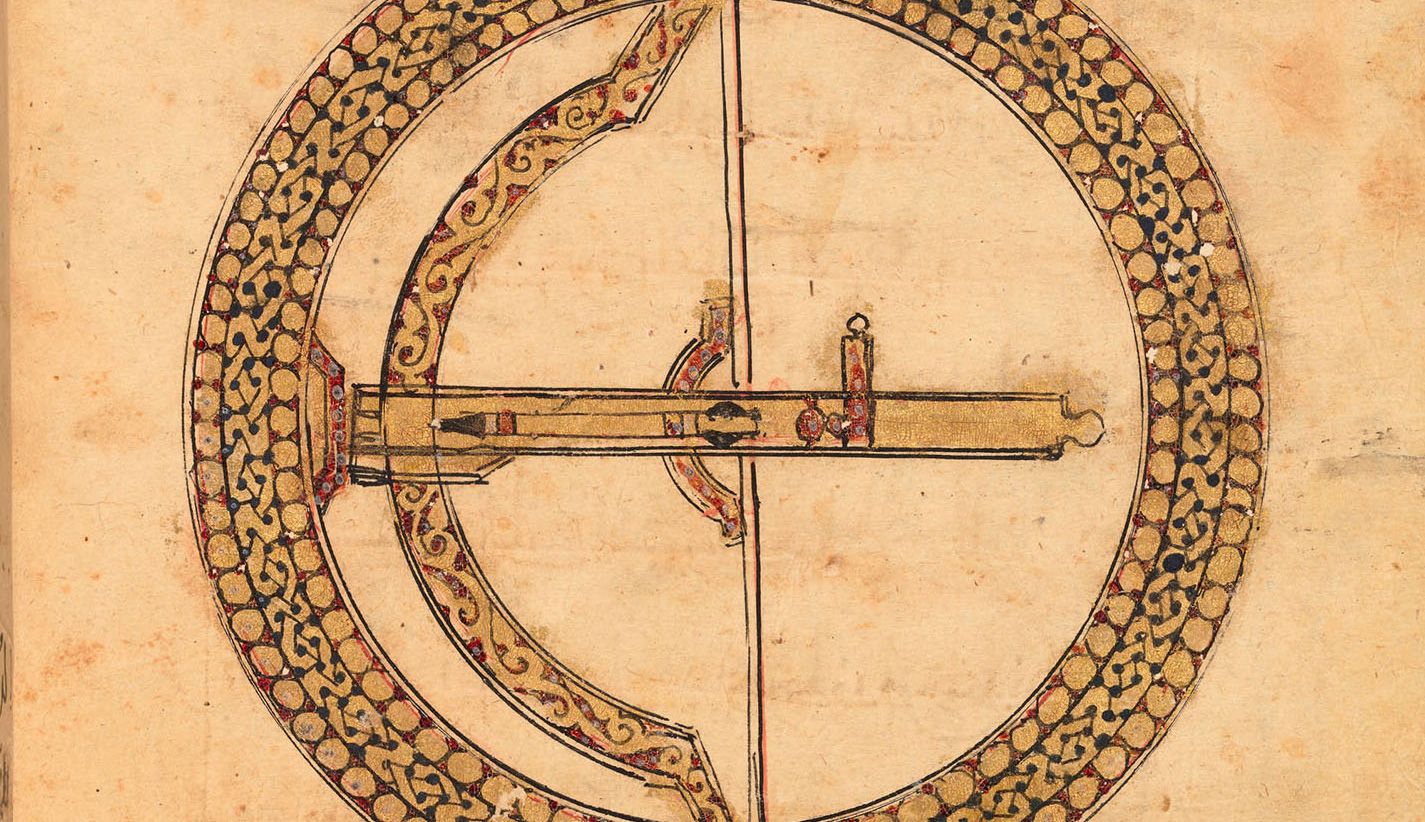

This multinational and multi-vocal atmosphere, the curators instruct us, “provided common cause and afforded peoples from different worlds the opportunity to meet through the shared language of commerce.” And indeed the fruits of this commerce lay all around us, beginning with a horde of 24-carat gold dinars discovered in 2015, moving on to 11th-century gold bracelets ornamented with delicate filigree, medieval glass- and tableware, bronze storage vessels, and bejeweled reliquaries meant to hold fragments of the holy cross (just the thing for titled tourists to bring back to Europe). Further attesting to Jerusalem’s impact on the consciousness of the time were European maps of the city and three astrolabes from the 11th and 14th centuries—one Christian, one Muslim, one Jewish; on each, “Jerusalem” is included as a site for which the instrument provided precise celestial calculations.

The next gallery highlighted “The Diversity of Peoples” to be found amidst the city’s throngs. “Jerusalem’s streets were never empty of strangers,” read the gallery’s epigraph, by the Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi (ca. 946-991). The wall panel elaborated:

No visitor failed to notice the rich mix of people on the streets of Jerusalem. Its astounding variety occurred across multiple dimensions: religious, linguistic, ethnic, and cultural.

The catalog, for its part, cites John of Würzburg, who, visiting Jerusalem in the 1160s and 1170s, listed the foreigners he encountered there: Greeks, Bulgars, Latins, Germans, Hungarians, Scots, Navarrese, Bretons, Angles, Franks, Ruthenians, Bohemians, Georgians, Armenians, Jacobites, Syrians, Nestorians, Indians, Egyptians, Copts, Capheturici, Maronites—and “many others.”

Each religion also harbored its own multiple sects. Thus, “Karaites and Rabbanites debated matters of [Jewish] religious law,” “Shiite and Sunni Muslims prevailed at different times,” and “nuances of doctrine and questions of allegiance split Christians.” But, we are assured, all shared a pacific and inspiring unity: a common reverence for the written word. In fact, “the city’s many madrasas, yeshivas, and monasteries” turned Jerusalem into “something of a college town, with a steady stream of students and scholars always coming and going.”

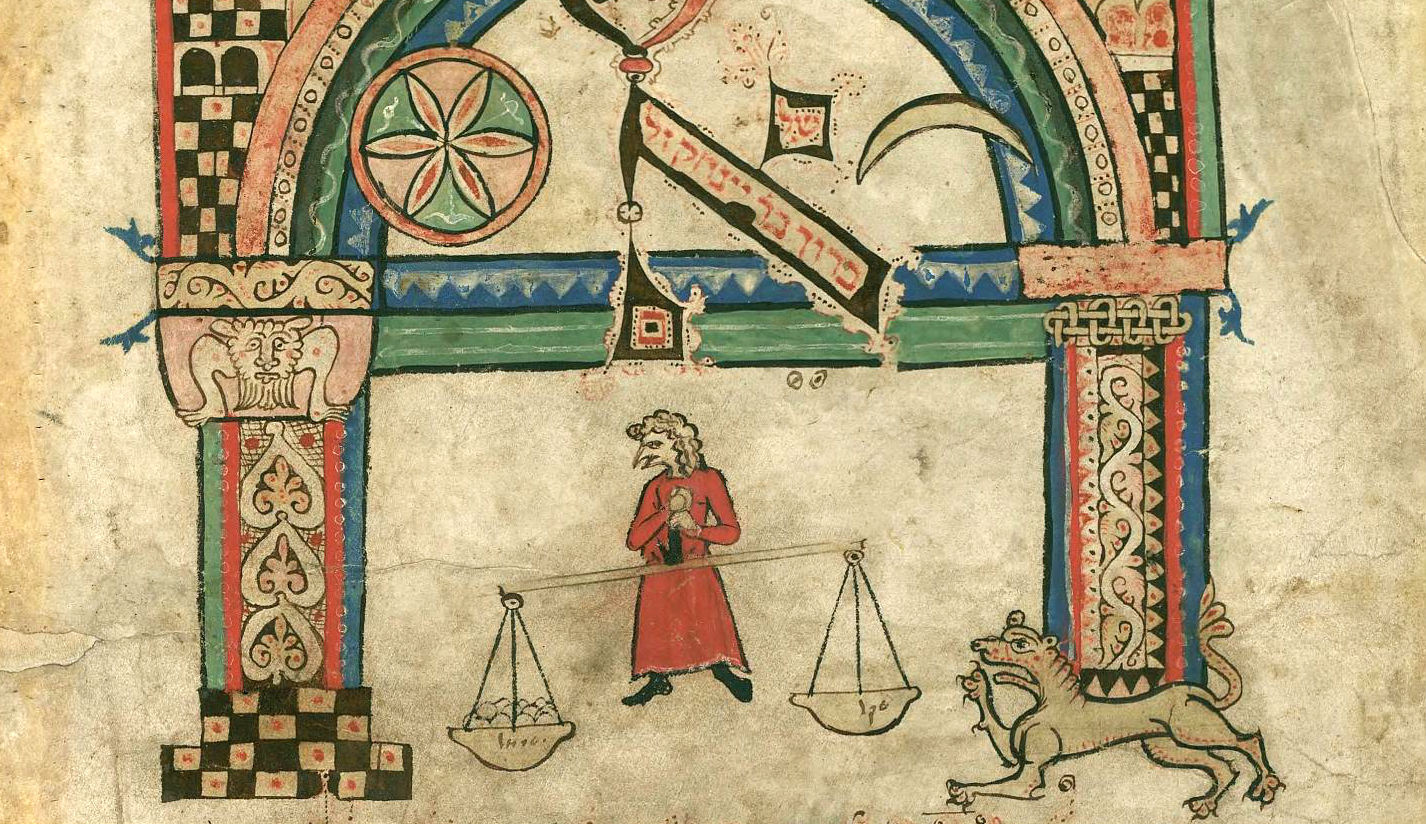

The artifacts assembled to substantiate this bustling and companionable diversity included a 15th-century cross from an Ethiopian church built as a surrogate for the Jerusalem churches considered lost to Christianity after the defeat of the Crusaders; a 1346 Quran open to a Sura hinting at the imminent Day of Judgment when, “according to Islamic belief, all will be brought to Jerusalem”; a page in Hebrew by Obadiah the Proselyte, an Italian Christian nobleman who became a priest before subsequently converting to Judaism; a 14th-century copy of the Four Gospels written in Arabic; a 13th-century Hebrew Bible in Samaritan script; a 13th-century New Testament in Syriac.

Underscoring the same ecumenical theme, each of the major religions then received a gallery of its own, devoted to its central religious structure: for Judaism, the Second Temple; for Christianity, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher; for Islam, the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque. The Christian gallery, for example, included objects attesting to the venerable church’s global significance along with such artifacts as a 12th-century missal used by its priests to celebrate Mass and fragments from a Crusader tomb once housed within its walls.

I’ll return later to the Muslim and the Jewish galleries, and to another gallery that sounded the one discordant note in the exhibition. But in the final hall— “The Promise of Eternity”— the three main religions were brought back together to reprise the symbolic importance of Jerusalem to each and to all. Here the reverential lighting, with scenes of modern-day Jerusalem projected onto the walls, with still more exotic artifacts displayed in full gleam and glitter, and in the presence of rare and gorgeously illuminated sacred manuscripts, the “fever” induced by the show was indeed intoxicating—as it was meant to be.

II. A Multiethnic, Multireligious, Multilinguistic Stew

What lesson, what single mental image of Jerusalem, emerges from a tour of these galleries and from the exhibition catalog? I’ve already alluded to it, and the organizers are hardly shy about enunciating it. The cultural phenomenon that most fires their enthusiasm, that forms their touchstone of both cultural and social excellence, is “diversity,” which they see not just as one aspect of life in medieval Jerusalem but as fundamental to its character. The front jacket of the catalog, taken from a 13th-century Syriac lectionary, shows a cross-section of Jerusalemites awaiting the arrival of Jesus. Visible on parapets are a man and a woman, side by side. “He has black skin,” the curators nudge us; “hers is white.” And they continue:

Another light-skinned woman, also with her head covered, holds a child with black hair, whose tawny hand reaches out to a lighter-skinned boy in a nearby tree. Young and old, men and women, people of many races, all cluster in the colorful context of a vibrant urban landscape.

This gathering of tawny, black, white, and light-skinned people may come from a 13th-century painting, but it is used here to convey a 21st-century message, as if a real medieval city had miraculously anticipated today’s progressive ideal, the determining principle by which the success of any society should be judged. Emphasizing the point, the curators draw a contrast between medieval Jerusalem, with its “spectacularly international character,” and Venice, Rome, and Paris at the same time: “None of these cities tolerated the same degree of religious diversity.” Moreover, they insist, Jerusalem’s “multiethnic, multireligious, multilinguistic stew” was good for everybody in it, shaping a “vibrant urban landscape” that embodied the values of “pluralism” and “extreme multiculturalism.” Most pertinent of all, and most emblematic of that spirit, was Jerusalem’s “interfaith” dialogue, which, as any visitor to the exhibition could see, engendered “art of great beauty and fascinating complexity.”

How did such a marvel come about? It developed, we learn, out of a long period of unusual stability. First, in the 1030s, “the Fatimid caliph who ruled over Jerusalem forged an agreement with the Byzantine emperor to rebuild the Holy City”: an ecumenical enterprise if ever there was one. Then, in 1099, European Christian Crusaders, having “achieved their improbable dream of conquering Jerusalem” from the Muslims—it was, admittedly, a “bloody victory”—created glorious buildings and works of art for almost a century. In 1187, the Muslim military leader Saladin “retook the city and rededicated its Islamic sanctuaries.” Afterward, from the late 1200s through the 1300s, “Mamluk sultans blessed with stable reigns promoted the city as a spiritual and scholarly center.”

“Throughout these years,” the curators conclude, “the city was home to more cultures, faiths, and languages than ever before,” in turn creating the environment from which “the city’s artistic and intellectual culture benefited” and transforming medieval Jerusalem into the “college town” that so captures their imagination.

True? It doesn’t require a surfeit of historical knowledge to bring these spirited declarations up short. To begin with, a mere glance at a map discloses that Jerusalem was hardly at the “crossroads” of anything. Situated in the Judean hills, it was on no major trade route and boasted no nearby large body of water. Its major features were its religious sites and artifacts and the pilgrims drawn to them. But its population during the centuries in question oscillated widely, and at one point was said to be no more than 2,000; one demographic study suggests that by the beginning of rule by the Ottoman empire—just after the period celebrated by the exhibition—Jerusalem’s population was at fewer than 1,000 households.

Next, consider the material evidence. In the first gallery, the elaborate array of gold, decorative ornaments, and antique textiles might certainly have seemed to suggest great enterprise, but where did these objects come from? The medieval gold jewelry was found in Ashkelon; the metalwork was unearthed in Tiberias and the port of Caesarea; the gold coins were likewise discovered near Caesarea; the golden bracelets are said to be from Egypt or Greater Syria; the textile fragments were from Egypt, Spain, and western India. In this entire gallery, only two artifacts were actually from Jerusalem: a 12th-century golden reliquary cross and a 14th-century clay-stem cup that may have been made by “potters working in the shadow of the al-Aqsa mosque.” Neither supported the large claims being entered for the artistic productivity of the city as a whole.

The paucity of local material evidence turned out to be characteristic of the exhibition as a whole. Only about 30 of its 200 objects were actually from the city being discussed. Nor, in the two galleries that did contain a high concentration of native objects, did those objects support the praise being whipped up for them. Thus, the gallery devoted to “The Diversity of Peoples” included four manuscripts from Jerusalem on loan from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York—including a late-9th- or early-10th-century Karaite commentary on Psalms and a transliteration in Arabic script of the Hebrew text of Jeremiah 20:3-5—plus a variety of Muslim documents, among them the only Quran in the exhibition identified as being of local origin. Similarly, the gallery devoted to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the most Jerusalem-laden of all, contained, as I noted earlier, the 12th-century missal used in the church and portions of crusader-era tombs and panels.

Neither of these two galleries, however, evoked the bustling give-and-take of an open city of the kind limned by the curators’ rhetoric. The Jewish manuscripts bespoke intra- and intercultural influence and argument—but such traces of external influence, linguistic variety, and disputation are as common on any page of the much earlier Babylonian Talmud as in these artifacts from Jerusalem in the High Middle Ages.

Meanwhile, in stark contrast to what could be seen in the gallery devoted to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the one devoted to the Islamic Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa mosque showed no major artifact directly associated with either of those two buildings or with their religious purpose or with Jerusalem itself. Direct connections came only from two exquisite 1909 watercolors by William Harvey and a 19th-century albumen print showing the mosque’s intricate 12th-century pulpit or minbar (which would be destroyed by arson in 1969 and rebuilt in 2007). Among the artifacts, a large 13th-century Quran was from either Egypt, Jazira (upper Mesopotamia), or Syria; a 14th-century Quran, open to a chapter about the Virgin Mary—a bit of museological ecumenicism—came from 14th-century Egypt or Syria; exquisite 14th-century mosque lamps were again from Egypt or Syria; a 13th-century lamp was from Damascus, and Egypt was the source of the textiles on display.

Was it impossible to procure any artifact or document that might illuminate the place of these two important Islamic sites in the history of, specifically, medieval Jerusalem? Were such things considered (by whom?) too sacred to be displayed in a museum? Or was omitting certain particularities of Islamic history and belief the only way the museum could maintain its gloss of interfaith harmony?

Whatever the answer to that last question—I’ll say more about it, and about the gallery devoted to the Temple, soon—the visitor was being told something that wasn’t being shown and shown something that wasn’t explained.

III. The Jarring Appearance of Holy War

For reasons of both history and the requirements of display, one gallery, “The Drumbeat of Holy War,” sat in the center of the exhibition, where it played a jarring role. “Intimately bound up with the belief in Jerusalem’s sanctity,” the text intoned, “was the ideology of Holy War.” And not just the ideology; from the 11th to the 14th centuries, we learn, “esteemed and learned men used the city as a lure, an excuse, a trophy, and an inspiration to wage battle in the name of God against those perceived as infidels.”

Wait, you might interject: in a city blessed with centuries of political stability, with a culture of cosmopolitan intercourse, an economy based on healthy commerce, and a populace that was the beau ideal of diversity—how have we suddenly arrived at something so incongruous as the energetic justification and actual pursuit of war, and Holy War at that?

Admittedly, a few puzzling hints could be found scattered elsewhere in the exhibition to the effect that things in Jerusalem were not completely harmonious: a quick mention of “conflict” alongside “coexistence,” or the lightly passed-over comment that “minorities of various kinds fared better or worse depending on the moment.” But such mild qualifications were invariably qualified in their turn. In the case of minorities, for instance, we were instantly reassured that, occasional mistreatment aside, “what remained constant was the city’s insistent heterogeneity,” along with that heterogeneity’s self-evident blessings and emoluments.

How, then, did the exhibition reconcile the idea of Holy War with the idea of medieval Jerusalem as a multicultural beacon? First, as one moved through the gallery, the idea of “wag[ing] battle in the name of God against those perceived as infidels” became more limited and attenuated. The main practitioners of this form of warfare, it emerged, were the Christian Crusaders who arrived from Europe “to claim Jerusalem as rightfully theirs,” a campaign that ended in victory in 1099 “with the merciless slaughter of the city’s inhabitants.” And indeed, most of the artifacts in this gallery were associated with the Crusaders or invoked them: a 12th-century charcoal image of a military “saint” on horseback, a 12th-century marble capital showing a rider trampling his enemy underfoot, a 13th-century tomb of a French knight, a 12th-century map of Crusader Jerusalem, and so forth.

The gallery “Holy War” was thus really meant to be an intrusion, an anomaly. The Crusader conquest of Jerusalem was, we were to think, a kind of one-off example of “extreme ethnic and religious cleansing.” But what, then, of the Islamic reconquest of the city, and what of the role of Islamic jihad in general? Strikingly, only one significant artifact in this gallery was associated with Islam: a gilded Treatise on Armor from early-12th-century Syria that “belonged to Saladin, famed to this day for bringing an end to European control of Jerusalem” and for “rededicat[ing]” its Islamic sites. Was Saladin, then, also involved in Holy War? Not according to the curators, who write in the catalog that it was the Crusaders who “fueled” the idea of Holy War, turning jihad—until then a concept of spiritual struggle alone—into one of military struggle. So the Crusaders not only introduced Holy War, they also caused Muslim leaders to distort their own religious teachings by adopting a kind of Holy War in response.

If this argument sounds familiar, it should: a similar argument has gained much traction in recent years among those who regard 9/11 and other Islamist terrorist attacks as a form of deserved blowback for prior Western offenses against Muslims. Intent on its own version of this judgment, the exhibition portrayed the Crusaders as both the single exception to, and the primal cause of any further disruption of, the multicultural paradise of medieval Jerusalem.

To accomplish this sleight of hand required some significant historical manipulation and revisionism. As the exhibition described it, for instance, the ecumenical rebuilding of Jerusalem under the Fatimid caliph in 1130 was necessary both because of earlier earthquakes and because of the “malfeasance” of the preceding caliph. Malfeasance? Earlier in the century, that caliph had ordered the destruction of all churches and synagogues in his Islamic empire; in Jerusalem alone, thousands of buildings may have been destroyed; the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was razed. Why was the nature of this malfeasance not mentioned? No doubt for the same reason that no mention was made of the Muslim massacre of Christians in Jerusalem in the 10th century—long before the Crusader conquest. As Eric H. Cline points out in Jerusalem Besieged: From Ancient Canaan to Modern Israel:

When the Byzantine armies won a series of victories in the field against the forces of Islam toward the end of May 966 CE, the Muslim governor of Jerusalem—who was also annoyed that his demand for larger bribes had not been met by the patriarch of the city—initiated a series of anti-Christian riots in the city. Once again churches were attacked and burned in Jerusalem. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher was looted and was so damaged that its dome collapsed. Rioters even killed the patriarch, John VII, who was discovered hiding inside an oil vat within the Church of the Resurrection.

In 1070-71, the Turkic emir Atsiz ibn Uvaq al-Khwarizmi captured the city, and six years later he murdered 3,000 Islamic rebels who had plotted against him, including some who had taken shelter in the al-Aqsa mosque. En route to Jerusalem in 1187, Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, slaughtered Christian communities throughout the Holy Land. Later, in 1229, despite the city’s alleged centrality to Islam and just decades after the fall of the Crusaders, a subsequent Ayyubid ruler offered Jerusalem to Frederick II, the Holy Roman emperor, in return for military assistance against a Muslim rival for power. In 1244, another Ayyubid ruler lost control of Jerusalem to Khawarezmi Turks who murdered much of the city’s population. In 1263, almost at the center of the era covered by the show, the Mamluk general Baibars attacked Acre and other cities held by Crusaders. As the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore relates in Jerusalem: The Biography, Baibars “received Frankish ambassadors surrounded by Christian heads, crucified, bisected, and scalped his enemies, and built heads into the walls of fallen towns.”

Nor did brutality, some of it intra-Islamic, stop there. Sacking, warfare, disruption, and rebellion extended all the way through the 14th century—the last span covered by the exhibition and hailed as the apex of “stable reign”—which featured a Mamluk sultan installed at the age of ten and later strangled in a coup and numerous other revolts and upheavals, a chronological account of which would be impossible to relate without seeming to have concocted an extravagant version of the very opposite of the exhibition’s claim for it.

IV. The Absent Presence of Jews

When the Iberian Jewish scholar Abraham Abulafia visited Palestine in 1260, he could get no closer to Jerusalem than Acre in the north because of the ceaseless fighting. Seven years later, the visiting Iberian eminence Moses Naḥmanides succeeded in making his way to the city and found there only two surviving Jews (or possibly two surviving Jewish families).

And this brings us to the subject I’ve largely postponed till now: namely, the situation of Jerusalem’s Jews. Although Jews and Jewish artifacts were certainly present in various ways throughout the exhibition, their presence was an exceptionally vague and fleeting one, functioning mainly to round out the museum’s picture of three supposedly equal and equivalent monotheistic faiths coexisting in some kind of balance. Thus, if Islam was represented by the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosque, and Christianity by the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Judaism had what the organizers describe as “The Absent Temple.” Solomon’s Temple, we were told, had been a “vast complex that housed the Ark of the Covenant”; centuries later, after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE, the site became “the focus of Jewish devotional practice both locally and from afar.” Jews, the exhibition noted, would visit Jerusalem “to mourn the destruction” of the Temple and to pray for its rebuilding.

How to present this absent Temple? Instead of artifacts connected to the structure (as in the gallery assigned to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher), or objects from other regions allegedly similar to those in the structure itself (as in the gallery assigned to the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock), the gallery assigned to the Temple offered medieval images and illustrations evoking either it or Roman-era Jerusalem more generally: a painted menorah in a 13th-century Italian manuscript of the Bible, an image of Jerusalem’s Gates of Mercy in a 13th-century maḥzor from Worms, enchanting wedding rings from the 14th-century Rhine valley of which one was decorated with a three-dimensional golden model of the Temple.

The show’s forced equivalences among the three monotheisms thus led to a severely skewed perspective. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher was materially substantial in the exhibition, possessing both a history till this day and a continuous (if periodically rebuilt) physical presence. The al-Aqsa mosque was granted an almost sublime aura as if it dwelled outside of history even as it, too, like the Dome of the Rock, remains very much physically present on the Temple Mount. The “absent Temple” was left as a ghostly image from the distant past, with no substantial reality.

Judaism’s presence in Jerusalem, in other words, was not just vague but itself an absence—a “poignant absence,” as the catalog puts it, especially when contrasted with the “richly appointed Christian and Muslim shrines of medieval Jerusalem.” But this poignancy is based on a false parallel. What, after all, was the meaning of Jerusalem for Jews? It was a meaning reflected not in art or artifacts of the kind that might fill galleries at the Met but in a millennium and more of liturgical, theological, philosophical, and legal texts bespeaking an unbreakable attachment as well as in sporadic, short-lived moments of messianic speculation and movements of return.

And that’s only part of the problem. Almost everything we know about Jewish life during the period of Christian and Islamic rule is at odds with the exhibition’s desire to evoke a wondrous world of diversity: a “college town” in which learning, debate, and cross-cultural fertilization conjoined in a thriving renaissance. Jerusalem in the 11th through the 14th centuries could not be considered a center of Jewish learning or indeed of Jewish life. There were such centers elsewhere, but in Jerusalem the community was not thriving at all; instead, it lived subject to extraordinary pressure.

For a minor part of the exhibition’s four centuries, Christians ran the city; for the rest, it was ruled by Muslims of one dynasty or another. As for the Jews, the best that can be said is that they survived. And when Jewish migration to the Holy Land picked up under Mamluk and later Ottoman rule—often as a result of persecutions in Europe—the way Jews could get physically close to the location of the “Absent Temple” was by seeking permission to pray along the Mount’s Western Wall. Everything adjoining the Wall was owned by Islamic authorities, and shops and dwellings proliferated there up through the period of the British Mandate. Not until after the June 1967 war did Israel clear the area in order to provide access to a holy site from which Jews had long been restricted and, for decades of Jordanian occupation, forbidden. Such was the ecumenical nature of medieval Jerusalem and its enduring heritage into the 20th century.

A letter from Maimonides, written in 1170 from Egypt, tells all. It was displayed in the gallery devoted to “The Diversity of Peoples”—presumably because it was written in Arabic using Hebrew script and involved an international issue. But its real “diversity” lay in the unique issue under consideration: the letter was written to raise funds needed to rescue Jews who had been abducted and were being held for ransom. In another letter on display, from 1125, the famous poet Judah Halevi, writing from Toledo, Spain, expresses his longing for Zion. But this letter, too, was related to the same matter, as the catalog informs us: the poet, as a community leader, “was involved in fund-raising for the ransoming of Jews taken captive by Crusaders.”

But it wasn’t just Crusaders who did the abducting. Though we would not have learned this from the exhibition, such kidnappings of “infidels,” including Jews, were for centuries commonplace Islamic tactics (and a source of many slaves)—so common, that an entire corpus of Jewish law was devoted to the means of responding to these extortionist demands: an aspect of “multiculturalism” that seems to have made a bad fit with the exhibition’s confident enthusiasms.

Not only was no notice taken of these matters but, among the three faiths, a tendentious impulse was at work in the exhibition to celebrate Islam above the other two and, in particular, to claim benignity for Islamic rule.

This sometimes went to absurd lengths. The catalog, for example, cites a cloth merchant commenting in 1488 on the styles of dress in Jerusalem and noting, for example, that “Moors wear white, with head wraps of fine cotton or toile de Hollande.” The hat of the Mamluk, he further states, was red, secured by a white cloth with a striped border. As for Jews, they wore yellow; and as for Christians, blue and white linen. The roster is taken as further evidence of diversity, in this case sartorial—in oblivion of the fact that where Jews and Christians were concerned, the color of items of clothing was regularly mandated by Islamic authorities who treated these populations as dhimmis, lacking important rights and required to pay additional taxes. If Jews were wearing yellow, it was likely not because of their taste in color.

Another example: in the catalog, Martin Jacobs, a professor of rabbinic studies at Washington University, suggests that in this period, “Jewish-Muslim relations seem to have been largely peaceful.” Lest we wonder what equivocations might lie behind the use of words like “seem” and “largely,” Jacobs gives an example: even during the relatively calm Mamluk period, he writes, certain places, like the Tomb of the Patriarchs (for Jews, the Cave of Makhpelah), were “off limits” to non-Muslims. Yet “even so,” he soothingly adds, although Jews couldn’t actually enter the site, they could stand “at a window in the outer walls of the sacred compound.”

A more disturbing description of these regulations actually appears in Jacobs’s book, Reorienting the East: Jewish Travelers to the Medieval Muslim World:

Under . . . Mamluk and Ottoman rule, Jews were permitted only as far as the seventh step outside the Haram al-Khalil’s [the Cave of Makhpelah’s] southeastern entrance, where they prayed next to a hole that was believed to reach the cave.

In the catalog, by contrast, deference rules: “modern readers,” Jacobs condescends, might be surprised to learn about such adverse regulations, but they needn’t be: after all, “Jewish pilgrims voiced little disappointment about their unequal access.”

A final example: Christian Crusaders, we were told, fled Jerusalem as Saladin’s army approached, abandoning elaborate pieces of carved marble. “These items were often so appreciated,” the wall text informed us, “that they were incorporated into the building fabric of the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsa mosque.” Was “appreciation” really the reason they were used? The Met would have us believe that the Islamic re-conquerors were as aesthetically fastidious as the Met’s own curators, and perhaps even more ecumenical.

Actually, of course, the deliberate reuse of building material by conquerors accompanied the equally deliberate practice of destroying the religious sanctuaries of the conquered population and building new religious structures on their ruins. Sometimes, no rebuilding was needed: in the 12th century, Saladin visibly marked his possession of the defeated party’s sacred spaces by turning Jerusalem’s Church of St. Anna into a mosque and its convent into a madrassa. Nor was he merely reacting to the prior cruelty of the Crusaders. In the early 8th century, the basilica of St. John the Baptist in Damascus had been leveled and became the foundation for the Great Mosque of the Damascus. The extraordinary Great Mosque in Cordoba, Spain, was built in the 8th century on the site of the destroyed ancient church of St. Vincent, using columns and capitals taken directly from it and other Christian and Roman-era buildings. In the 20th century, the Jordanians plundered tens of thousands of tombstones from the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives and used them for paving blocks.

This is not “appreciation”; it is theft and degradation, and well understood as such. Some magnificent capitals were on display in the Met exhibition, built during the Crusader period for the church in Nazareth. They were extraordinarily well preserved. Why? Because, as the Crusaders fled, they had been buried to protect them from Saladin’s invasion, lying safe in the earth until being exhumed in the 20th century.

V. A Refusal to Confront History

The final gallery of the exhibition, “The Promise of Eternity,” summed up and extended the themes adumbrated throughout. “Whatever their differences,” we were told, the three religions all held “that Jerusalem serves as the meeting place of God and humanity, the gateway to heaven, and the terrestrial threshold of the eternal world.”

It would take another and even longer essay to examine this assertion carefully. For example, Jerusalem is not mentioned at all in the Quran, and later interpretations vary widely; does Islam generally subscribe to the Met’s formulation on its behalf? In Christianity, is Jerusalem really considered the gateway to heaven, or the place where God and humanity meet? In fact, the three faiths’ different approaches to the city reflect fundamental differences in the nature of their beliefs—another large issue at odds with the roseate view that the keys to the best aspects of Jerusalem’s past lie in its supposed cosmopolitanism and internationalism, and should become our own lodestars today.

In each of the major galleries, this impression and its attendant message were reinforced by video interviews with contemporary Jerusalemites hailing the themes of diversity and ecumenicism and hoping for even more of both in the future. One scholar offered a prescription that could have been crafted by the Met’s PR firm: “I think there was much more interaction [in earlier eras] than we appreciate today. Instead of focusing on the history of Jerusalem as a sequence of wars, it would be more about the exchange—the cultural exchange—the debate.” An Israeli writer, far from reacting to the missing Jewish presence, seemed perfectly willing to suppress or abrogate his own identity: “I feel that the absent Temple is not just a Jewish symbol. I feel that it is a universal symbol. Every person, every culture, can relate to a lost dome of innocence.”

Diana Muir Appelbaum was one critic who recognized that something was seriously awry in this “take” on Jerusalem as a place inhabited by three different faiths and traditions living side by side and really quite similar, perhaps even identical, in their vision of the city. (Another unfooled critic was Maureen Mullarkey, who sharply exposed the denigration of Christianity and the blatant promotion of Islam.) In her online review, Appelbaum fastened on a wall label identifying the Temple Mount as a place “variously understood as the site of Abraham’s sacrifice, the location of the tabernacle in the Temple of Solomon, and the point of departure for the Prophet Muhammad’s Ascent to Paradise.” Appelbaum commented acidly: “Muhammad’s ascension to heaven and Abraham’s near-sacrifice of his beloved son are legendary accounts. The location of the ancient Temple, by contrast, is an archaeological and historical fact.”

In today’s climate, one cannot but hear in the Met’s conjoining of fact with legend the suggestion that the fact in question is itself just another legend, if not a fabrication. For several decades, indeed, explicit statements in exactly this mode have multiplied with abandon. At the Camp David peace summit in July 2000, Yasir Arafat declared to President Bill Clinton that “Solomon’s temple was not in Jerusalem, but Nablus.” In 2002, Ikrima Sabri, the mufti appointed by Arafat, announced: “There is not even the smallest indication of the existence of a Jewish temple in Jerusalem in the past. In the whole city, there is not even a single stone indicating Jewish history.” In 1996, Walid Awad of the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) ministry of information stated: “The fact of the matter is that almost 30 years of excavations did not reveal anything Jewish. . . . Jerusalem is not a Jewish city, despite the biblical myth implanted in some minds.” In November 2010, the PA released a study arguing that the Western Wall was actually part of the al-Aqsa mosque: “This wall was never part of the so-called Temple Mount, but Muslim tolerance allowed the Jews to stand in front of it and weep over its destruction.”

The virus has gone international. United Nations documents and resolutions now typically omit any Jewish attachment to the Temple Mount. And of course the recent Resolution 2334 of the UN Security Council, which the outgoing Obama administration did not veto and likely went out of its way to encourage, deliberately specifies that “East Jerusalem”—an area that includes the Temple Mount—is “occupied Palestinian territory.” As if to lend ex-post-facto credibility to such contortions, the Islamic waqf that controls Islamic edifices on the Temple Mount has been systematically excavating and destroying millennia of archaeological evidence and disposing of it as garbage.

Obviously, the Met doesn’t support anything like Temple denial; but its inability to characterize the “absent” Temple’s importance or to give a sense of the Jewish historical experience in Jerusalem, along with its exaggerations of the glories of Islamic rule and its relentless focus on “internationalism,” unmistakably lends itself to the purposes of those who engage in that nefarious activity—and at least one essay in the catalog, on the Dome of the Rock, silently endorses it. That essay, by Robert Hillenbrand of Edinburgh University, simply omits any mention of something called the “Temple Mount”—this, despite the fact that early Islamic sources did the exact opposite, referring to the site as Bayt al-Maqdis (Hebrew: beyt hamikdash) and to Jerusalem itself as madinat bayt al-maqdis (“the city of the Temple”). Instead, Hillenbrand locates the Dome of the Rock “on the “Haram al-Sharif, the vast open esplanade that, . . . largely empty in the late-7th century,” was described variously as a rubbish dump and a “place accursed” since the Temple was destroyed there. In other words, the Dome of the Rock was erected on unused land—an assertion that is in itself a complete perversion of the very reason why it was built there in the first place. The Mount was called a “dungheap” by St. Jerome in the 5th century: a fulfillment of Christianity’s triumph and the Jews’ curse. Today a comparable historical erasure is being advanced by other parties.

The show’s refusal to confront history in any serious way; the failure to find artifacts that match its multicultural thesis; the depiction of the Jewish presence in Jerusalem as an “absence”—all of these contribute to the impression that, for the organizers of this exhibition, the undeniable facts of ancient Jewish history were the very things that could never be acknowledged. (As, in an opposite way, were the undeniable facts of medieval Islamic history.) Better by far to imagine Jerusalem in this fantasy as an international city without a hint of historical Jewish sovereignty, and a mythical place in which all faiths enjoyed equivalent standing.

In 1995, Edward Said, writing in polemical opposition to continued Israeli control of Jerusalem, yearned for the triumph instead of the “massive Palestinian-Muslim-Christian-multicultural reality in Jerusalem.” Said’s view of Jerusalem’s supposed “multicultural reality,” which he desired to enhance and advance, was just as distended as the view on display at Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven, preserved now in its catalog and in the message it has so effectively promulgated. At least Said, a pro-Palestinian radical, was being open about his ambitions. In the Met’s soft-focus presentation, a variant of the same view came bearing the imprimatur of one of the most imposing aesthetic authorities in the West, and was thus all the more easily gulped down by viewers and reviewers besotted with its dreamy and meretricious promise.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of Jerusalem’s reunification in the Six-Day war of June 1967, it is necessary to bear this fact in mind: one of the few times in Jerusalem’s history when conquest was not followed by the demolition and appropriation of major holy sites was in the aftermath of that war, when Israel became the sites’ guardian and expanded access to them while ceding control to the authorities of different faiths. This ongoing relationship has hardly been untroubled, but it is far closer to an ideal of genuine diversity than any yet dreamed of while in the throes of Jerusalem Syndrome or its latest mutations.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Jerusalem