The United States decision on December 6, 2017 to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and to transfer the American embassy there from Tel Aviv was one of the more momentous acts of diplomacy ever undertaken by a U.S. administration in Middle Eastern affairs. So much so that nobody believed President Donald Trump would actually do it, until he did.

When he did, most Israelis and most pro-Israel Americans approved or were positively delighted. By contrast, the American political class, Republicans and Democrats alike, was stunned—even though the president had merely fulfilled a legislative mandate, the Jerusalem Embassy Act, that had been passed near unanimously by both houses of Congress during the presidency of Bill Clinton 22 years earlier in 1995, only to be repeatedly deferred by successive White Houses for over two decades. Veteran Near East Arabists in the Department of State, for their part, put on a stern face and obeyed.

What came next was no surprise. The “international community,” from the United Nations General Assembly to the European Union, not to mention the Arab League and the World Islamic Conference, stridently rejected the American initiative. Two weeks after the decision was announced, 128 of the 193 member states of the General Assembly approved a resolution—ES-10/L.22—drafted by Turkey and Yemen and demanding that “all states comply with Security Council resolutions regarding the Holy City of Jerusalem and do not recognize any actions or measures contrary to those resolutions.” Only eight countries, including Israel, sided with the United States.

This international condemnation relied on a venerable notion: that the legal status of Jerusalem—does it belong to Israel? To the Palestinians? To both? To neither?—was a settled matter, and that the answer to those questions was “none of the above.” Instead, international law and legal precedent had carved out the city as an international ward.

There is, indeed, a long legal history, built of many resolutions and agreements, to just that effect. But there are two problems with this settled conviction. First, its roots in law have been egregiously misrepresented. Second, the claim that Jerusalem actually belongs to the state of Israel rests on strong legal, moral, and demographic foundations.

Let’s start with the law.

I. What International Law Is

What is international law? It’s easy enough to doubt, if not to mock, the idea that there is such a thing—that is, a universally recognized corpus of legislated rules binding the behavior of nations. Nevertheless, for our purposes, let’s posit that international law exists, that it enjoys an impressive pedigree, and that it compels or should compel the assent of the civilized world.

Today, it is commonly assumed that international law is decided mainly by the United Nations and adjudicated, if disputing countries consent, by the UN’s wholly owned arm, the International Court of Justice. Thus, almost every argument raised against President Trump’s decision on Jerusalem cites various UN resolutions saying that Jerusalem is not the capital of Israel. Particularly prominent is Security Council Resolution 470, passed on August 20, 1980, which condemned the enactment by Israel’s parliament of a constitutionally binding law enshrining Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, and called on the governments that had already established embassies in that city to withdraw them. Resolution 470 largely rested, in turn, on previous Security Council resolutions from 1967 and 1968 that denied Israel any right to change Jerusalem’s “status” as a result of the June 1967 Six-Day War.

But does the United Nations possess authority to legislate through such resolutions? After all, it is no more than an association of sovereign countries that, ultimately, remain free to abide by UN resolutions or to ignore them. And if the UN is not a supergovernment, what of its resolutions?

As is well known, these are of two types. Resolutions by the General Assembly—like, most recently, ES-10/ L.22—are passed by a majority of members. According to the UN Charter, they are not legally binding. Rather, they testify to a political view held by a majority of countries at a given moment that can change over time. Thus, the infamous Resolution 3379 of November 10, 1975, determining, by a majority of 72 to 32 votes with 32 abstentions, that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination,” was revoked sixteen years later by Resolution 4686 of December 16, 1991, by 111 votes to 25 with 13 abstentions.

Yet, while unauthoritative in themselves, General Assembly resolutions sometimes give rise to Security Council resolutions, some of which are formulated as “decisions” that are legally binding on all UN member states. Under Chapters VII and VIII of the UN Charter, such Security Council resolutions can impose economic or military sanctions on a rogue nation. All Security Council resolutions require not only a majority of the Council members but the acquiescence of the five permanent members, each of whom is invested with veto power.

So much by way of quick background. Even if one questions the UN’s legal authority out of hand, as many do, it is one thing to reject on those grounds its case against the recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel; it’s another thing to vindicate Israel’s case. As it happens, however, there is ample documentation of the Jewish people’s special relation to the Holy Land and thus to the city of Jerusalem.

First, that special relation was implicit in the Balfour Declaration of November 2, 1917 and in the various ensuing documents that referred to it, including the San Remo Conference resolution of April 25, 1920 and a joint resolution of the U.S. Congress on September 21, 1922. The claim was explicitly recognized by the June 3, 1922 British White Paper on Palestine, and in the preamble to the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine of July 24 of that year, which begins: “Whereas recognition has . . . been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country. . . .”

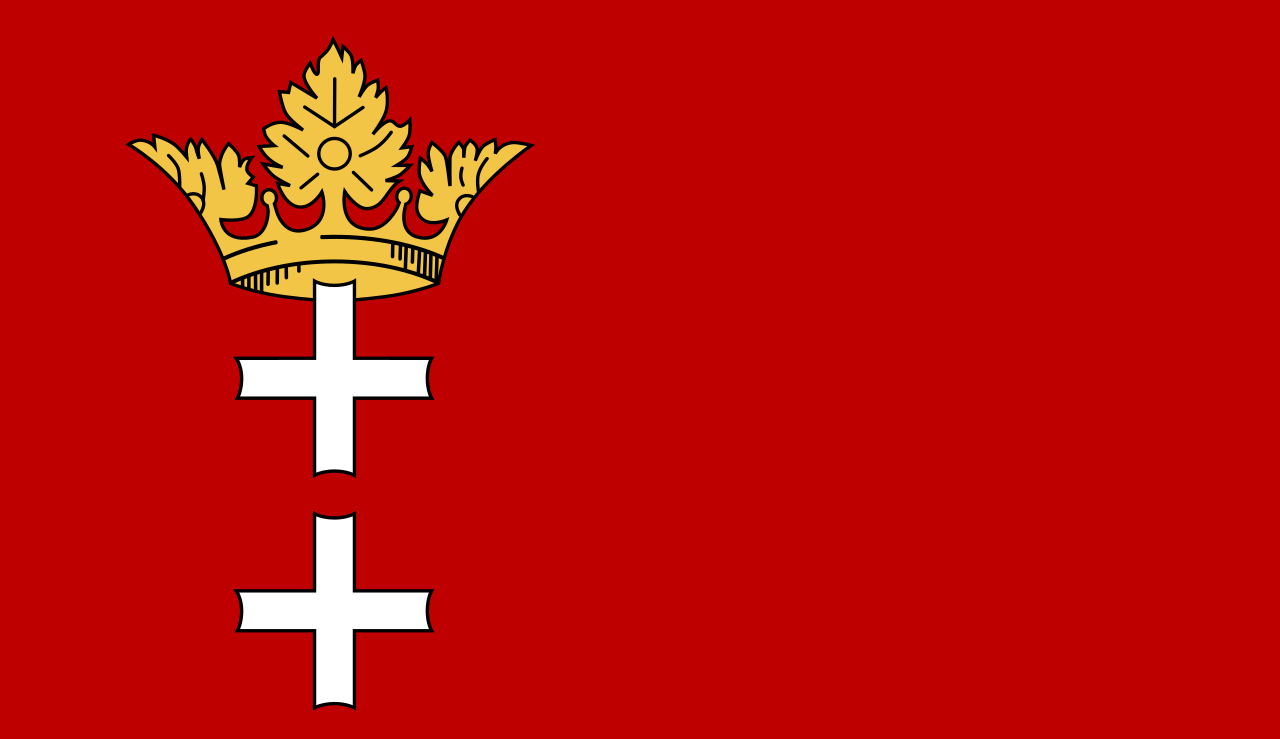

Second, Jerusalem was from 1920 to 1948 the seat of Palestine’s administrative government. True, the November 1947 UN plan to partition Palestine between the Jews and the Arabs proposed converting Jerusalem into an entity (corpus separatum) separated from both states—an issue to which we’ll soon return. But that plan, though endorsed by the UN General Assembly, was never more than a proposal. The Arab states and Palestine’s Arab leadership rejected the proposal, and it was never implemented. As Jerusalem was Palestine’s seat of government before Israel came into being, so it remained for the Jewish state after independence in 1948.

In addition, whatever may be the legal status of the 1993 Israel-PLO arrangement known as the Oslo Accords, that arrangement pointedly left the Jerusalem issue to a further stage in the peace process. Arguably that implicitly validated the status quo—Jerusalem as the capital of Israel—in the interim.

Third, those nations that engage in bilateral relations with the state of Israel also recognize Jerusalem de-facto as its capital, since their leaders or representatives regularly go to Jerusalem to meet Israel’s leaders or address the Israeli parliament there. Under international law, de-facto recognition is as valid as de-jure recognition for at least as long as the de-facto circumstances prevail.

In other words, it is both a gross inconsistency and a breach of the accepted rules of international relations for the many UN member states that recognize Israel and whose leaders or representatives visit Israel’s leaders and legislators in Jerusalem—a list that among the major EU powers includes Germany, France, and the UK— to denounce President Trump’s decision as legally inadmissible.

II. The Half-Life of an International Jerusalem

Why, then, if such long-established precedent exists for regarding Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, has the “international community,” including in some instances the United States, so strenuously disregarded Israel’s rights in the city? The answer can be expressed in terms of a metaphor: just as it takes particular isotopes a certain amount of time for their radioactivity to fall to half of its original strength, and then more time to decay completely, so some political facts or understandings enjoy a similarly ghostly “half-life” long after they have been swept away by real-world circumstances—especially when their survival serves the interests of a variety of parties.

This brings us back to the 1947 UN plan for the partition of Mandatory Palestine and especially its provisions regarding Jerusalem.

The partition plan was drawn up by the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). The UN General Assembly’s two-thirds majority vote in favor of the plan on November 29, 1947 was celebrated by Palestinian Jews (the yishuv) and by Jews abroad as a vindication of the Zionist dream. Even today, its anniversary is a national holiday of sorts in Israel. Palestinian factions and the Palestinian Authority remember the date mournfully as part of the unfolding of their national “catastrophe” (nakba) of those years.

In one respect, the UN plan was decidedly pro-Jewish and pro-Zionist: it explicitly provided for the creation of a Jewish state. But the plan was also deeply flawed, and its context has been grievously and often willfully misunderstood by the international community.

At the time of the plan’s passage in 1947, any authorized international support for a Jewish state was an asset that the Zionist movement could not turn afford to down, whatever the actual nature of that support and whatever the proposed state’s shape or size. No doubt most members of the special committee, like those who worked to get the plan approved, fully understood what was at stake and were mindful not only of the international community’s failure to rescue European Jewry during World War II but also of the plight of hundreds of thousands of stateless Holocaust survivors still confined in DP camps.

The drafters thought that a territorial partition, for which precedents existed earlier in Ireland and very recently in India, was a step toward approval of a Jewish state by Britain, the United States, and the international community as a whole. But the flaws, to repeat, were many and deep. The two-state plan, as enunciated in UN Resolution 181, gave more land to the Arabs than was envisioned by the Jewish and British fathers of the Balfour Declaration and the Palestine Mandate.

Moreover, each of the two states envisioned by the plan consisted of a few largely disconnected enclaves that were strategically unviable and economically bereft of federal or confederal arrangements—in turn implying the need for international supervision and perhaps limitations on both states’ sovereignty. Last but hardly least, by severing Jersualem from the Jewish state and creating a corpus separatum for that predominantly Jewish city, the plan incorporated ideas that belittled the Jews’ historical connection with Jerusalem and impugned their ability to safeguard the holy sites of all religions there.

One may understand, accordingly, why some (mainly right-wing) Zionists rejected the partition plan from the outset. But the official leadership, dominated by left-of-center parties, believed that the main political gain—a UN-endorsed Jewish state—outweighed any shortcomings: better a state through partition than no Jewish state at all. In fact, Jewish leaders in Palestine had floated their own partition plan a year earlier that included an international zone in Jerusalem.

There was also a deeper reason for the Jewish leadership to be open to a compromise scheme: chances were that, at the end of the day, any such scheme would not really matter. Once a Jewish state was created, its actual shape would no longer be determined by any pre-established UN plan but rather by facts on the ground. In the speech he delivered to the central committee of the Jewish labor movement on December 3, 1947, the essence of which he would reiterate in the May 1948 deliberations over the text of Israel’s declaration of independence, David Ben-Gurion hinted at this logic:

Clearly, the UN resolution mutilates our ambitions and infringes the international promises delivered in the wake of World War I. Quite obviously, it reduces the Jewish country’s area. One cannot fail to notice that Jerusalem is to become an international city, . . . that almost all the mountains have been taken away from us, . . . and that the Jewish state’s borders are bizarre, to say the least. For all that, I think that this is the greatest asset ever granted to the Jewish people throughout its entire history. So long as such a state is born and thrives. . . .

Besides, a sovereign Jewish state would instantly absorb hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants and become strong enough either to fight if, as was likely, the Arab side opted for war. or to negotiate on more favorable terms. Even many UNSCOP members, including the committee’s chair, Sweden’s Emil Sandström, admitted that partition could not be implemented “without resorting to force.” Also, in secret negotiations, the Hashemite kingdom of Transjordan made clear that it would both go to war and lay claim to the Arab-populated areas in Cisjordanian (roughly, “West Bank”) Palestine, thus in effect ensuring that the Palestinian Arab state controlling the West Bank would be Transjordan and not a new Arab state.

If this explains why a partition of the land could be endorsed by the Zionists, at least as a tactical and temporary move, the same reasoning applied, mutatis mutandis, to their willingness to forgo an argument over Jerusalem: the place that, by any measure, was the most Jewish entity in the whole country.

In strategic terms, the Jews were much weaker in Jerusalem than elsewhere. The Holy City was comparatively isolated from the bulk of Jewish Palestine, which lay on the Mediterranean coast and in Galilee. The large ultra-Orthodox community in the city had for decades remained apart from the main organizations of the yishuv, and its residents were largely unfit for military or paramilitary training. Complicating matters further, although some Jews in Jerusalem had in fact joined self-defense networks, they tended to favor the units associated with the Jabotinskyan wing (Etzel and Leḥi) rather than the pro-leadership units (Haganah and Palmaḥ) that were in charge elsewhere; coordination between the two was far from easy.

Under such circumstances, a corpus separatum was a sensible temporary option. And “temporary” is again the key word. Were a Jewish army to take and hold ground in Jerusalem, the corpus-separatum idea might be forgotten as part of a partition plan that never came into effect. Were the Jews to fail there, the corpus-separatum scheme might allow Jewish leaders to win some international protection for Jews remaining in the city. In the meantime, showing a willingness to compromise was an important diplomatic asset.

III. A Christian-Ruled City

One reason for compromising over Jerusalem was this: at the time, “internationalization” was a code word for the continuation of, specifically, a Christian presence in both Jerusalem and the Holy Land; in turn, Jewish acquiescence in such a continued presence was necessary for Christian agreement to, or support for, a Jewish state. This crucial but often overlooked point merits a brief summary.

For about a century since roughly the 1850s, a steady Christian revival had taken place in Jerusalem. While weaker than the Jewish revival in demographic terms, it was much more visible, and spectacularly so, in terms of institutions, buildings, and property. Under the Ottoman Land Property Act of 1857, most Christian sects and communities were allowed to buy as much land as they could afford, including large tracts of desert or semi-desert outside the Old City’s walls, either in order to protect existing Christian shrines or buildings or to create new neighborhoods. So much land was accumulated that from the 1920s on, Christians began leasing property to the Jewish National Fund or private Jewish developers.

Much of this Christian activity increased after 1917-18 when the British conquered Palestine from the Ottomans in World War I. For various Christian denominations and for Christian-oriented Europeans, this development looked very much like a long-delayed opportunity to repair the humiliating defeats incurred in the Crusades, especially (after the creation of a predominantly Christian country in Lebanon) Europe’s defeat at the hands of Saladin in the 13th century.

With that in mind, no wonder that, in the early post-World War II years, the Christians of Palestine and their allies abroad now feared that the imminent British withdrawal from the country would jeopardize their world-historical opportunity. A predominantly Arab Palestine would be a predominantly Muslim Palestine, with little patience for Christianity; for some, a Jewish Palestine raised similar concerns. Such concerns needed to be calmed, even if at a high cost—hence the significance of a Jewish willingness to turn Jerusalem into an “international” enclave.

Recall that this was still 1947: a decade before the final dissolution of the European colonial empires. The United Nations and the “international community” remained largely dominated by Christian countries. An international Jerusalem was thus expected to be, for all practical purposes, a Christian-ruled city.

Factored into these calculations were, in addition, the ongoing negotiations between the Jewish leadership and the Catholic Church in particular.

Until 1944, the Holy See had adamantly opposed both Zionism and Jewish immigration to Palestine. In the immediate postwar years, however, Pope Pius XII took a more nuanced position. Meeting with an Arab Palestinian delegation in early August 1946, the pontiff preached peace and deplored “the persecutions that fanatical anti-Semitism” had unleashed on the “Hebrew people.” He made sure his words were reported in the New York Times, seen by the Church as the supremely influential “Jewish paper” in America.

Following discreet talks between the Holy See and Jewish and Zionist representatives, and the latter’s evident readiness to entertain the idea of international rule in Jerusalem, the Vatican dropped its anti-Zionist stand and professed neutrality in the dispute over Palestine. In June 1947, Monsignor Thomas MacMahon, the American prelate in charge of Christian Arab affairs at the United Nations, confided to UNSCOP:

We are completely indifferent to the form of the regime which your esteemed committee may recommend, provided that the interests of Christendom, Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox, will be weighed and safeguarded in your final recommendation.

One month later, Brother Simon Bonaventure, a Franciscan representative of the Custody of the Holy Land, using exactly the same argument, set “the protection of Christian services” as his order’s sole concern. In turn, the Holy See’s “indifference” or neutrality made it easier for UNSCOP and the representatives of Catholic countries at the UN, especially Latin American ones, to support the partition plan.

This Christian angle also explains why the corpus separatum, as envisioned by UN Resolution 181, was extended geographically well beyond the Mandate-era borders of the Jerusalem municipality. It aimed to put under “international”—that is, Christian—control as many Christian communities and holy sites as possible, including Bethlehem and Bayt Jalla.

By the same token, however, outlying Muslim communities were also to be included, with the effect that the Jewish majority in the new “international Jerusalem” would be diluted from its then-60 percent of the municipality’s populace to 49 percent—still a majority in relative terms but short of the absolute demographic dominance in the city which Jews had enjoyed since the 1870s.

But here we are getting ahead of ourselves. In the event, the Jewish leadership’s tactical calculations proved correct, and the corpus separatum was never implemented. The war, which started immediately after November 1947 as an intergroup conflict and then, after the British withdrawal in May 1948, developed into a full-fledged international war between the new state of Israel and seven neighboring Arab countries, was largely won by the Jews. The ceasefire lines, agreed upon by early 1949, gave 75 percent of Mandate Palestine to Israel. And the country’s demographic balance also changed overnight as more than a million Jewish immigrants, mostly Holocaust survivors, poured in while over a half-million Arabs fled to the Arab-controlled areas of Palestine or other Arab countries.

As foreseen, the most difficult fighting took place in Jerusalem, but at the end of the day Israel managed to retain most of the prewar Jewish city. The one glaring exception was the Jewish neighborhoods of the Old City. These had been pounded by the Jordanians at the inception of hostilities, and in May 1948 their 2,000 Jewish inhabitants had been forcibly removed.

Israel did manage to keep Mount Scopus, the first seat of the Hebrew University, as an enclave in northern Jerusalem, and Mount Zion as a second enclave just outside the walls of the Old City. It also managed to link the Israeli sector in Jerusalem to the rest of the country. But the Old City’s Jewish holy sites, including its 35 synagogues, were either destroyed or, in the case of the Western Wall and the cemetery on the Mount of Olives, left in Arab hands. Several Jewish settlements outside the municipality’s boundaries, including Atarot, Neveh Yaakov, and the five Gush Etzion communities, had likewise fallen to Arab forces.

In fact, as defined by the 1949 ceasefire lines, Israeli Jerusalem was encircled by hostile forces on three out of four sides; only the western side was open, linked to the rest of the country by a corridor less than ten kilometers wide. After the war, sporadic terrorist incursions, shelling, and sniper fire would occur not only on the Israel-Jordan and Israel-Syria ceasefire lines but also in the Jerusalem area. Veteran Jerusalemites still remember the large no-man’s-land and buffer zones, complete with barbed wire, that for two decades separated the Israeli sector in Jerusalem, or “West Jerusalem,” from the Jordanian-held sectors.

All of this would of course be transformed by Israel’s spectacular victory in the Six-Day war of 1967.

IV. Descending into Fantasy

As we’ve seen, the main legal consequence of the 1947-1949 war and the ensuing ceasefire agreements was the death of the 1947 partition plan, including its special provisions for Jerusalem, which Israel’s Arab neighbors had rejected. Nevertheless, officials of various countries argued illogically that the plan’s Jerusalem provisions somehow still remained alive. Of this descent into fantasy, the Catholic Church, eager to ensure the preservation of Christian power in Jerusalem, was the prime promoter.

On October 24, 1948, in the wake of an Israeli operation to enlarge the western corridor out of Jerusalem, Pope Pius XII issued an encyclical “commending” a special regime for Jerusalem and the neighboring areas, to be “grounded in international law and guaranteed by international law.” A second encyclical, issued in April 1949, three months after the Israeli-Jordanian ceasefire, called again for an “internationally guaranteed regime” in the Holy City. Notably, neither in the first nor in the second instance did the Holy See claim the partition plan’s provisions to be still valid as such: it just demanded that, whatever the final outcome of the Arab-Israeli conflict, some kind of international control or supervision be retained in greater Jerusalem.

Over the following eight months, the Vatican lobbied intensively at the United Nations to reinstate the corpus separatum—and actually succeeded. Resolution 303 (IV), passed by the General Assembly on December 9, 1949, boldly called for the city to be “established as a corpus separatum under a special international regime” and “administered by the United Nations.” No less boldly, it delineated the corpus separatum’s borders to include “the present municipality of Jerusalem plus the surrounding villages and towns, the most eastern of which shall be Abu Dis; the most southern, Bethlehem; the most western, Ein Karim (including also the built-up area of Motsa); and the most northern, Shua’fat.”

This extravagant petition ignored both the legal implications of the 1947-1949 war and the resulting facts on the ground; no subsequent UN resolutions would ever quote it verbatim. Seen at the moment as a diplomatic triumph for the Vatican, Resolution 303 (IV) would in the longer run prove a non-starter for Catholics and other Christians. Jordan hardened its anti-Christian stance in Jerusalem and its environs until the area was taken by Israel in 1967; Yasir Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas would follow the Jordanian example when, under the 1993 Oslo Accords, the PLO became entrenched in the West Bank and Bethlehem.

Nevertheless, the fantasy created in 1949 would grow and increase as Resolution 303 soon became the main inspiration for the doctrine, endorsed by the U.S. Department of State until 2017 as well as by almost every other foreign ministry in the world, according to which even “West Jerusalem” was not part of Israel.

Diplomacy is based on routine, repetition, and cross-reference. Once a resolution has been voted, it can be constantly mentioned or quoted in further resolutions—or in the discussions that lead to their writing. The more a resolution is mentioned or quoted, the more untouchable it is assumed to be. As soon as it has been embraced by one international organization, others are likely to endorse it, as are their ever-multiplying branches and subsidiaries. General Assembly resolutions are cited by resolutions of the Security Council and of UNESCO, WHO, other UN agencies, the EU, the African Unity Organization, the Arab League, the World Islamic Conference, the Non-Aligned Movement, and every “progressive” NGO under the sun.

Diplomats and law professors then claim that the resolution has become “international law,” even if it stands in blatant contradiction to longstanding principles of international law. The claims are further amplified through political networks among like-minded parties who call themselves the “international community.”

For most of the cold-war era, the United Nations and its agencies grew enormously, accreted dozens of recently established states, and departed from the largely Western and democratic political culture of its founding members. As a result, General Assemblies and other councils or commissions were increasingly dominated by anti-Western, anti-American, and anti-Israel majorities. More often than not, they have encountered no other check than an American veto at the United States Security Council. Worse, there are instances when the United States itself, inadvertently or deliberately, does not employ its veto and lets things pass.

Thus, on July 4, 1967, less than one month after the Six-Day War, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 2253 (ES-V). It read:

The General Assembly, deeply concerned at the situation prevailing in Jerusalem as a result of the measures taken by Israel to change the status of the city, (1) considers that these measures are invalid; (2) calls upon Israel to rescind all measures already taken and to desist forthwith from taking any action which would alter the status of Jerusalem.

When asked what the “status of Jerusalem” was, UN experts and other commentators cited both the Israeli-Jordanian ceasefire of 1949, which had been superseded by the June 7, 1967 Israeli-Jordanian ceasefire, and Resolution 303 (IV) of 1949. Both of the two latter actions negated the terms of the 1949 ceasefire. But the UN experts knew what they were doing. Till today, many foreign-ministry officials, including in the UK’s Whitehall and the French Quai d’Orsay, still claim both that the 1949 armistice line in Jerusalem—the “green line” that till 1967 divided Israel from Jordan—is an “international border” even though it merely marks the 1949 ceasefire lines. They also inconsistently claim that the part of Jerusalem on the Israeli side of that armistice line did not belong to Israel. By and large, officials of the U.S. State Department similarly subscribed to that inconsistent position.

For one reason or another, the U.S. representative at the UN abstained from the vote on the 1967 resolution. Ten months later, on May 21, 1968, that resolution served, among other texts, as a precedent for Security Council Resolution 252, which employed stronger language against Israel on the Jerusalem issue:

The Security Council . . . deplores the failure of Israel to comply with the General Assembly resolutions mentioned above, [and] considers that all legislative and administrative measures and actions taken by Israel . . . which tend to change the legal status of Jerusalem are invalid and cannot change the status of Jerusalem.

Once again, the United States abstained. But this time, it was a Security Council resolution. Building on both resolutions, more Security Council resolutions on Jerusalem were passed in 1969, 1971, and 1980, without being checked by Washington.

The upshot: “international law” was continually invoked to Israel’s disadvantage, so much so that, for many years, Israeli diplomats or jurists avoided serious discussions about it, even when (or especially when) its absurdities were egregiously evident.

V. The French Example

Thus has the Church’s intervention on behalf of “internationalizing” Jerusalem lived on—even in the minds of those who aren’t aware of it and would consider themselves well past such parochially religious concerns. I am speaking here of the European countries and in particular of France.

French support for the Zionist cause ran high in the 1945-1948 years, and it is no coincidence that so many covert activities, including the tragic 1947 odyssey of the SS Exodus bearing 4,500 Holocaust survivors to British Palestine, only to be denied entry and returned to France, were masterminded in Paris or operated on French soil. In the 1950’s, France and Israel became close strategic partners; Israel’s military victories in 1956 and 1967, both of which owed much to state-of-the-art French armaments, were celebrated as French victories by proxy.

Even in later years, after the alliance lapsed, large sectors of the French public retained sympathy for and curiosity about the Israeli experience. Aside from its achievements in security, science, medicine, and high-tech, Israel is still praised in the French media, and even by the political class, as in many ways a model country. Indeed, on July 1 of this year, Anne Hidalgo, the socialist mayor of Paris, had no qualms inaugurating a Place de Jérusalem (“Jerusalem Plaza”) in front of the city’s newly built Jewish European Cultural Center, thus underscoring the Jewish character of the Holy City. Attending the ceremony as an honored guest was Moshe Leon, the Israeli mayor of Jerusalem.

For all of that, however, the French foreign ministry in particular has been so utterly obstinate in its denial of Israel’s legitimacy, especially when it comes to Jerusalem, as to arouse suspicions of institutional anti-Semitism. Some observers have half-seriously wondered whether the secret agenda of the Quai d’Orsay, more or less in line with 19th-century European fantasies, is not to wage a ninth crusade in the Holy Land, almost 800 years after the failure of the French-led seventh and eighth crusades—this time not against the Saracens but against the Hebrews. Old habits of mind die hard.

Even more rigidly than did the Obama State Department, the Quai d’Orsay insists both that the 1949-1967 “green line” is an international border and, contradictorily, that Jerusalem is an entity unto itself, separate from Israel. Visiting French officials are warned not to set foot in “East Jerusalem” and above all not to come near the Western Wall. (Not all of them comply.) French citizens in Israel voting in French elections are divided geographically between those residing “in Israel” and those residing “in Jerusalem.” There is only a single French consulate-general in the city, squarely in the West Jerusalem sector, which works essentially as an embassy to the “State of Palestine” while reluctantly also catering to the general populace and to the overwhelmingly Jewish French expatriate community.

What’s going on in these weird passive-aggressive slights becomes clear when you consider the Quai d’Orsay’s insistence that France should play a special role in Jerusalem as the protector of holy sites. Many of these sites happen, of course, to be Catholic, but one that has recently come to wider public attention is not: the Tombs of the Kings, located in the “East Jerusalem” neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrakh.

An intricate and beautiful complex of rock-cuts tomb, the site is believed to be the ancient burial place of Queen Helene of Adiabene and her sons, a royal family in northern Mesopotamia who converted to Judaism in the 1st century CE. Jerusalem Jews regarded it as a holy place even before it was fully excavated, and there were always groups of people praying or reciting Psalms there; Muslims did not interfere.

In 1863, Louis-Félicien de Saulcy, a French adventurer, numismatist, and amateur archaelogist, unceremoniously stole the sarcophagus of Queen Helene, bones included, and presented it to the Louvre. The bewildered Jewish community in Jerusalem appealed to the chief rabbi of France, who in turn requested the help of Amélie Bertrand, a rich Christian lady of Jewish origin who was known to be concerned with Jewish issues. Through the French consul in Jerusalem, Bertrand bought the site in the early 1880’s and, as a marker attests, entrusted France “to allow the Jerusalem Israelites to pray there.”

After Jerusalem was reunited in 1967, the French consulate declined to re-open the tombs to Jewish worshippers and instead renamed the site as an “East Jerusalem Palestinian landmark.” going so far as to allow a Jerusalem Festival of Arab Music there in 1997. A 2000 issue of Palestine-Israel Journal, a militant pro-Palestinian publication, lauded the event for “developing burgeoning cultural links between Palestine and the rest of the Arab world.”

A Jerusalem foundation dedicated to the Tombs of the Kings has challenged France not just on the issue of the Tombs proper—which the French closed for renovation in 2010 and only now have grudgingly re-opened —but also on the sarcophagus and bones illegally “donated” to the Louvre. Ironically, the same Quai d’Orsay that is so highmindedly devoted to alleged “international decisions” regarding Jewish Jerusalem turns adamantly parochial when it comes to perceived French interests, especially where its relations with Arabs are concerned.

But then, France has no monopoly on hypocrisy; its example is all too representative of its main EU partners as a whole, thereby providing us with yet another reason to dismiss arguments—putatively on the basis of international law—against Israel’s possession of Jerusalem.

Moreover, as I mentioned earlier, there are still other other grounds on which to base the claim that Jerusalem is Israel’s. To these we can now turn.

VI. The Jewish Jerusalem

The apportioning of territory and the delimitation of borders are intricate matters under international law. As it happens, many territorial disputes have been decided instead by referenda on self-determination citing facts on the ground, preeminently including demographic facts on the ground, or by bilateral or multilateral agreements taking such realities into account.

This is true of cities as well as of extended territories: one precedent is the incorporation of the culturally Italian city of Trieste into Italy under the London Memorandum of 1955 and the Treaty of Osimo in 1975.

By this important precedent, how does Jerusalem stack up?

The first-ever reliable demographic survey of Jerusalem was conducted in 1845 by the Prussian consul Ernst-Gustav Schultz. Out of a total population of 16,410, living mostly in the old walled city, he found 7,120 Jews, 5,000 Muslims, 3,390 Christians, 800 Turkish soldiers, and 100 Europeans. In other words: well before the modern onset of Zionist-inspired immigration, the Jews, at 43 percent of the population, already formed the single most populous group.

Twenty-three years later, in 1868—about the time of Mark Twain’s famous journey to the Holy Land narrated in The Innocents Abroad—the Jerusalem Almanack, a publication intended for Western visitors, divided the population evenly between Jews (9,000 inhabitants out of 18,000) and non-Jews (5,000 Muslims and 4,000 Christians), with Jews once again being the single most populous group.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Jerusalem started to develop, outside Sultan Suleiman’s walls, along Jaffa Road to the west, Nablus Road to the north, and Jericho Road to the east. Rings of new neighborhoods were built, along with many public facilities. In the process the city took on, as we’ve seen, a more pronounced Christian character with impressive new buildings including churches, convents, and hospitals funded by the Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant powers.

But the city’s demographic expansion owed essentially to the Jews. By 1889, out of 39,175 inhabitants, Christians numbered 7,115 (18.1 percent), Muslims 7,000 (17.8 percent), and Jews 25,000 Jews (63 percent).

The growth of Jerusalem as a chiefly Jewish-inhabited city continued apace until World War I. While, according to the historian Martin Gilbert, “the population of Jerusalem nearly doubled between 1889 and 1912,” the Jewish population almost tripled.

One of the most revealing sources in this respect is the Guide de Terre Sainte (Guide to the Holy Land) published in the early 20th century by Father Barnabé Meistermann, a French Franciscan friar, under the aegis of the Custody of the Holy Land. A monument of religious, historical, and aesthetic erudition, the work offers a detailed, practical report on the various entities involved: the Holy Land proper, which is to say present-day Israel and Jordan, plus Italy, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Asia Minor, and Constantinople.

According to the Guide’s first edition, published in 1907 and quoted by Gilbert in his Jerusalem: Illustrated History Atlas, there were at that time 58,900 inhabitants: 10,900 Christian Arabs (18.percent), 8,000 Muslim Arabs (13.5 percent), and 40,000 Jews (67 percent). An updated edition, scheduled for release in 1914, was suspended at the outbreak of World War I and was afterward edited to reflect the geopolitical consequences occasioned by the fall of the Ottoman empire and the end of eight centuries of Muslim control in Jerusalem and the Land of Israel.

Regarding the population of Jerusalem, the second edition cites a later prewar survey conducted in 1910 by the German statistician Davis Trietsch. Out of the city’s 92,000 inhabitants, Trietsch recorded 17,000 Christians (18.4 percent), 13,000 Muslims (14.1 percent), and 62,000 Jews (again at 67 percent).

Broadly speaking, this early-20th-century ratio between Jews and Arabs (about two-thirds/one-third) remains a demographic reality to this day, despite both strong Jewish population growth on the one hand and repeated episodes of violence on the other hand, the latter including anti-Jewish riots and pogroms, wars, terrorism, and forced migrations of both Jews and Arabs.

Thus, in 1944, according to a British census, there were 97, 000 Jews in Jerusalem out of 156,980 inhabitants (61.7 percent); in 1967, when the city was reunited under Israeli rule, there were 195,700 Jews out of 263,307 inhabitants (74.3 percent); in 2017, 564,897 Jews out of 882,652 inhabitants (64 percent).

If one were to consider “greater” Jerusalem as a metropolis rather than a municipality, the ratio would still hold. Such a metropolis would include, in addition to the present Israeli municipality of Jerusalem, the pre-1967 Israeli municipalities of Mevasseret Zion, Motza Ilit, Tzova, Even Sapir, Ora, Abu Ghosh, Ma’aleh Haḥamishah, and the post-1967 Israeli municipalities of Ma’aleh Adumim, Pisgat Ze’ev, Gilo, and the Gush Etzion area, as well as the Palestinian Authority municipalities of Ramallah, Birah, Abu Dis, Bayt Jalla, Bayt Sahur, and Bethlehem—in all, a population of roughly 1.2 million.

Of these inhabitants, Jews would number 764, 000 (63 percent) and Arabs 450,000 (37 percent). If one were to exclude the 150,000 Arabs in the PA municipalities but include those in the pre- and post-Israeli municipalities, the Jewish proportion would stand at 72 percent and the Arab proportion at 28 percent.

The impressive demographic strength of Jerusalem Jews, in absolute as well as relative terms, is the result of both migratory influxes (including immigration from foreign countries) and high birthrates (especially among the Orthodox and ḥaredi communities). The demographic resilience of Jerusalem Arabs rests on similar trends: on the one hand, relatively high birthrates; on the other hand, migration from other Middle Eastern countries until 1947, then an influx of refugees from other parts of Palestine after the 1948 war, followed by economically or politically induced migration from Arab Palestinian villages and semi-nomadic Bedouin tribes in the West Bank from the 1950s on.

This is true at least of Muslim Arabs in particular; it does not take account of the great demographic change that has occurred within the Arab population of Jerusalem. Until the early 1920s, Christian Arabs outnumbered Muslim Arabs, but they have steadily declined ever since. By 2015, there were only 12,400 Christian Arabs in Jerusalem as against 307,300 Muslim Arabs (3.8 percent of a total Arab population of 319,700 or 1.4 percent of the total Jerusalem population of both Arabs and Jews). Even in an enlarged Jerusalem metropolis encompassing the mainly Christian municipality of Bayt Jalla and the formerly Christian but now predominantly Muslim municipality of Bethlehem, there would be no more than 30,000 Arab Christians in all (2.4 percent).

More than demographic factors alone (e.g., lower birthrates and lower rates of inmigration) have been at work here. From 1949 to 1967, as we noted earlier, Jordan’s Hashemite government ruling the Arab sector in eastern Jerusalem steadily enforced a policy of Islamization. Quite naturally, Arab Christians, fearing for their future, began to emigrate en masse, their numbers dwindling by almost two-thirds from 1944 to 1967.

Under Israeli rule from 1967 onward, the numbers of Christians have stabilized but not improved, especially as similar hardships have been inflicted since 1993 in areas under the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority. Indeed, the declining Christian population under Jordanian and Palestinian Authority rule suggests that only the Jewish state can effectively protect the Christian minority.

And so to return to the Jews and to sum up: Israel’s claims to Jerusalem are supported not only by the moral and legal considerations we’ve reviewed earlier but by compelling demographic data showing that, for nearly two centuries, the Holy City has hosted a Jewish plurality, and for the past century and a half an absolute Jewish majority.

VII. The Myth and the Reality

What does this history teach us? It rebuts the widely held idea that Jerusalem’s status is the subject of an international “agreement.” That idea is nothing but a myth—a myth that serves the political purposes of certain interested parties. Those parties argue that Zionism was an interloper in the city, a newcomer throwing chaos into the mix of a calm, stable, mostly Arab-Muslim town that for centuries had existed sometimes under Christian control, at other times with a heavily Christian element.

None of this is true. The truth is that, even in earlier times, Jerusalem was always in ferment, a kind of Wild East in which all major groups, not just arriviste Jews, were scrambling to build something for themselves. As for the modern proposal to “internationalize” the city, it was first and foremost a device to please the Catholic Church, then in itself a formidable world power and a foreign one in the Holy Land. In this context, the idea of Jerusalem as an “international city” is a piece of Western “colonialist” history, while the Jewish connection to Jerusalem is ancient and indigenous.

Fortunately, the global drumbeat of condemnation had no effect on the White House decision. The United States embassy was effectively transferred on May 14, 2018 (the 70th anniversary of Israel’s independence according to the Gregorian calendar) from the Tel Aviv seaside promenade where it had been located since 1966 to a large compound in the Arnona neighborhood in Jerusalem that had been used for a couple of years as a consular facility. The older consulate in Jerusalem, which had hitherto functioned as the de-facto U.S. mission to the PLO, and reported not to the American ambassador in Tel Aviv but directly to the Secretary of State, now also, like almost all U.S. consulates everywhere, reports to the State Department through the local U.S. ambassador. In line with this policy of normalization and recognition of reality, the administration has also recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights and the U.S. ambassador has acknowledged that Israel will someday incorporate into itself the major Israeli West Bank settlements.

What is more, the administration’s example soon inspired other nations, even some who had voted for the UN resolution condemning the move. In its aftermath, smaller countries like Guatemala and Moldova emulated the American initiative. Several EU countries—Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania—have spoken about deciding similarly, and have also blocked a newly drafted statement reiterating the EU’s denunciation of the American embassy transfer. Larger countries like Brazil and Australia have said they might consider moving their embassies in the future, or if not their embassies then at least some diplomatic offices: measures that, if not always bold—diplomatic habits of caution die hard, too—are at variance with the judgment of People Who Matter.

Even more significantly, the 2017 decision failed to generate a backlash against President Trump’s Middle Eastern policies, as Mahmoud Abbas and other anti-Israel hardliners had expected, or to prevent Arab or Muslim countries from getting involved with the Trump administration’s “peace plan” and upgrading their own economic, cultural, and/or strategic ties with Israel.

In this context, the American recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel should not just be praised as a contribution to the Jewish state’s vital interests and as an innovative approach to the Middle East’s problems. Groundbreaking as those achievements are, they also remind us of the need to remain alert to how the international order came about and whom it was designed to serve; what exactly is the role of international law and how it should be approached; and, when it comes to the history and destiny of Israel and the Jewish people, what is the irreplaceable value of optimism, grit, leadership—and numbers.

Tuesday, July 9, 2019: Some passages in this essay have been updated for clarity and precision since its publication on Monday, July 8.—The Editors.

More about: Catholic Church, International Law, Israel & Zionism, United Nations