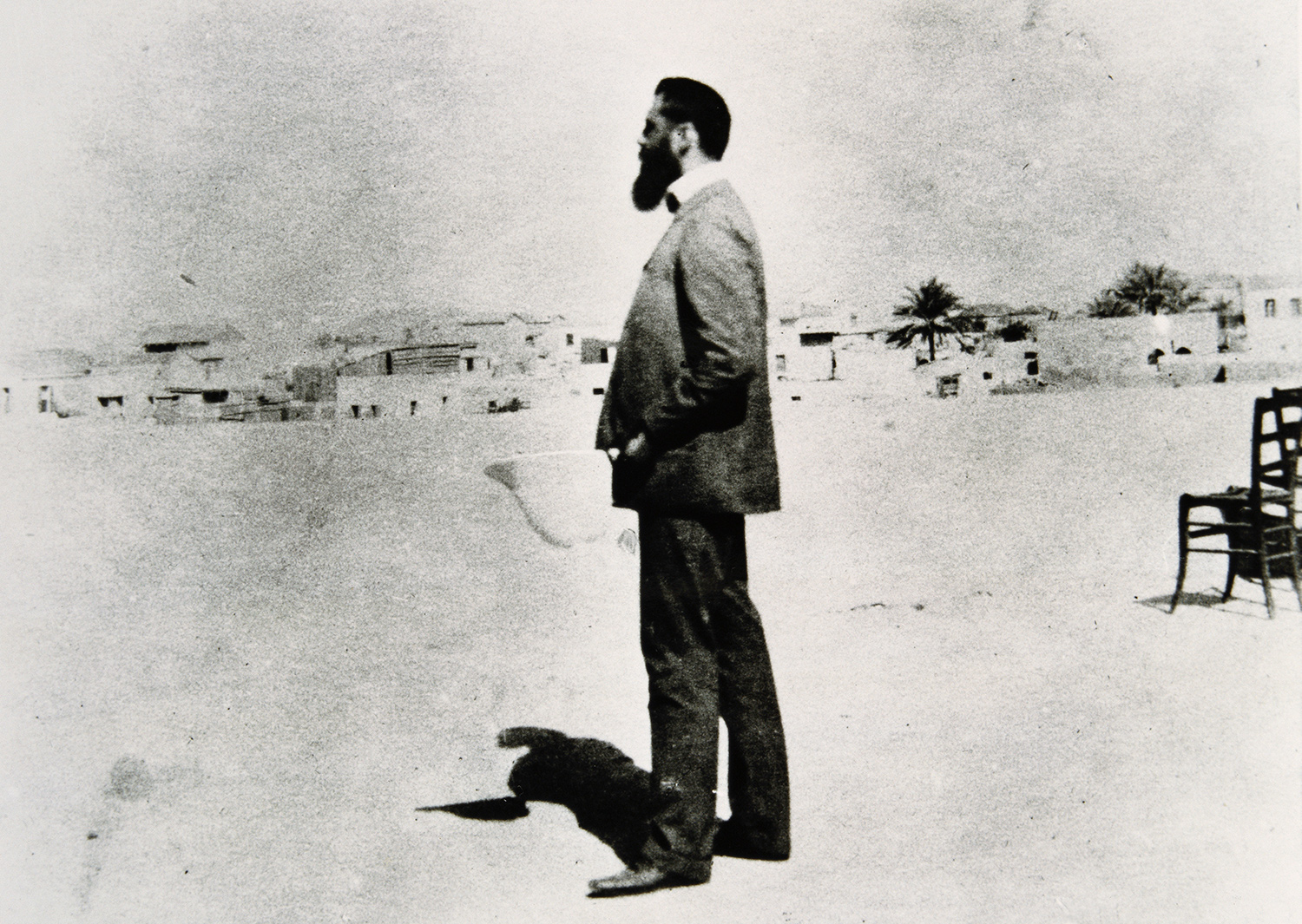

Theodor Herzl in Palestine in November 1898. David Wolffsohn, Imagno/Getty Images.

Not since Moses led the 40-year Exodus from Egypt did anyone transform Jewish history as fundamentally as Theodor Herzl did in the seven years from the publication in 1896 of his pamphlet The Jewish State to his historic pledge in 1903 on the subject of Jerusalem at the Sixth Zionist Congress. Then he died suddenly in 1904, at the age of forty-four.

In 2017, on the centennial of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, Britain’s historic promise to facilitate a Jewish national home in Palestine, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said the Declaration resulted “largely thanks to Herzl’s brilliant appearances in England.”

Herzl created something out of nothing. He turned Zionism into a mass movement. He created the organizational and economic tools for the World Zionist Organization. Perhaps above all, he gained access to kings and counts . . . and this was no small thing [because a Jewish statesman] did not exist at the time, . . . certainly not one who was a journalist and playwright, and who was only thirty-six years old. It was unthinkable.

How did a man opposed by Orthodox rabbis (who believed a Jewish state should await the messiah), Reform rabbis (who wanted a Jewish state relegated permanently to the past), assimilated Jews (who feared accusations of dual loyalty), Jewish socialists (who considered any type of nationalism reactionary), and Jewish public figures (who thought the whole idea absurd) create a worldwide movement? How did a young writer with no political connections, no ties to Jewish organizations, and no financial backing beyond his own resources negotiate with leading figures in the Western world’s ruling empires, engaging in what Netanyahu called “inconceivable diplomatic actions” that would lead to the Balfour Declaration and eventually the creation of the state of Israel?

Those are important questions. Even more important a question is that of why Herzl did all this, given his minimal ties to Judaism and the Jewish people during his early adulthood. While he had a bar mitzvah and attended a predominantly Jewish high school, he had sought assimilation ever since his days as a university student in Vienna. Nor was he religiously observant as an adult: when his son was born in 1891, he did not have him circumcised. On December 24, 1895, six weeks before the publication of The Jewish State, Herzl was at home lighting a Christmas tree for his three children.

For many years, biographers believed Herzl became a Zionist after covering the Dreyfus trial in 1894 in Paris, as a foreign correspondent for a Viennese newspaper. More recently, however, scholars have shown that Herzl’s embrace of Zionism had virtually nothing to do with that case.

The story of Herzl thus presents a mystery. He came, seemingly, out of nowhere. At the beginning of 1895, no one would have predicted that the thirty-five-year-old literary editor of Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse would propose the formation of a Jewish state, present the idea to London’s Jewish elite, publish his historic pamphlet, establish the political, financial, and intellectual institutions for a state-in-waiting, negotiate with emperors, kings, dukes, ministers, the pope, and the Ottoman sultan, hold six Zionist congresses attracting hundreds of delegates from more than twenty countries and regions around the world (their numbers increasing each year), produce two remarkable diplomatic achievements in 1903 that set the stage for the Balfour Declaration—and then die heartbroken, less than a decade after he began, in 1904.

In 1897, a few days after the First Zionist Congress concluded in Basel, Herzl wrote in his diary that he had “founded the Jewish state”:

If I said this out loud today, I would be answered by universal laughter. Perhaps in five years, and certainly in 50, everyone will know it.

In 1947—50 years later—the United Nations endorsed a Jewish state in Palestine. Six months after that, David Ben-Gurion proclaimed its independence in Tel Aviv—a city that did not exist in 1897—under a massive photograph of Herzl, flanked by two flags identical to the one Herzl had hung in Basel.

In the long history of the Jewish people since their formation in the barren wilderness of the Sinai, no one had done so much, of such consequence, in so little time.

I. The Embodiment of the Assimilationist Ideal

Growing up, Herzl was the quintessential product of the new Jewish age. Indeed, as the historian Carl Schorske has noted, he embodied the assimilationist ideal. Born in 1860 in Budapest to cultured, upper-middle-class Jewish parents, he grew up in the decade that saw the emancipation of the Jews enacted into Hungarian law. His family was, in Schorske’s words, “economically established, religiously ‘enlightened,’ politically liberal, and culturally German.” Young Jews living in cities such as Warsaw, Berlin and Vienna had unprecedented opportunities in European society. In 1878, at eighteen, Herzl entered the University of Vienna to study law.

In early 1881, Herzl was admitted to Albia, a selective dueling fraternity that was part of the German nationalist student movement. At the time, German nationalism was not a threat for a Jewish student such as Herzl, but rather an attraction. This movement endorsed liberal values; it was a brand of progressive politics, opposed in Austria to the conservative rule of the Hapsburg empire—although anti-Jewish elements were present that would eventually overwhelm the movement. A number of illustrious Jews in the 1870s and early 1880s belonged to German nationalist student societies, including Gustav Mahler, Sigmund Freud, and Arthur Schnitzler.

With his admission into Albia, Herzl was joining the sons of aristocrats and professionals in a fraternity that formed a distinctive elite, with members wearing special insignia on campus. Herzl’s entry into the top echelon of student society was the kind of achievement Jews had been seeking for their children for more than a century. Fencing was an important social institution for students, through which they could demonstrate their courage. After joining Albia, Herzl spent four hours a day taking dueling instruction (two hours from the fraternity and two privately); in his initiation duel, he received a scar on his cheek as his badge of honor.

Herzl took as his fraternity name “Tancred”—the title character of Benjamin Disraeli’s novel, Tancred, or the New Crusade. Disraeli had just ended a six-year term as the first Jewish-born British prime minister. In the novel, Tancred is a young Christian aristocrat who studies at Oxford and then travels to the Holy Land. There he meets Eva, a young Jewish woman, who defends “the splendor and superiority” of the Jews, and changes Tancred’s view of them.

Tancred was Disraeli’s effort to uphold the Jews and express his view that the ideal faith was one that recognized both Christianity and Judaism. In taking the name “Tancred”—an enlightened Christian who learned first-hand about the Jews and came to admire them—Herzl chose a name laden with significance, suggesting that he viewed assimilation as a reflection of Jewish honor.

Over the next two years, however, things began to change for both the Jews as a people and Herzl as an individual.

In 1881-82, two seminal books appeared, only one of which the twenty-one-year-old Herzl read. The unread one was Auto-Emancipation: An Appeal to His People by a Russian Jew, written anonymously by Leon Pinsker, a well-educated Jewish physician in Odessa. Pinsker wrote it after pogroms swept through Russia, in more than a hundred towns, following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by an anarchist group that included a Jew.

Pinsker argued—in a book Herzl would not discover until after he wrote The Jewish State—that the “Jewish Question” could be solved only by national independence. The book had both intellectual force and literary grace, and it would become, in David Ben-Gurion’s words in 1953, “the classic and most remarkable work of Zionist literature.” But it wasn’t treated that way at the time. Pinsker wrote it in German, seeking to appeal to the educated Jews of the West. He traveled to Austria and Germany in search of Jewish leaders to support his ideas—and found none at all. The chief rabbi of Vienna dismissed him as mentally ill. Faced with no significant Western reaction to his book, Pinsker concluded dispiritedly in 1884 that it would take the messiah—or “a whole legion of prophets”—to arouse the Jews. He called them a “half-alive people.”

The book Herzl did read in 1882 was Eugen Dühring’s The Jewish Problem as a Problem of Race, Morals, and Culture, which was an extended pseudo-scientific argument for anti-Semitism—a word first coined three years earlier by Wilhelm Marr, a German agitator who believed “the Semitic race” was trying to destroy Germany. Unlike Marr, however, Dühring was a renowned intellectual and philosopher who drew on Charles Darwin’s influential ideas about the role of “favored races” in “the struggle for life.” Dühring argued that Jews were an inferior race that must be purged to save Germany, and his book was widely read not only by intellectuals and students, but also by the wider Austro-Hungarian public, making anti-Semitism broadly acceptable in Central European society.

Herzl was stunned by the book. It was, he wrote in his diary, “so well-written, [in] excellent German” by “a mind so well trained,” that he even agreed with some of Dühring’s criticisms of Jewish manners and social characteristics—although, unlike Dühring, he thought they were the result of centuries of social segregation rather than inherent Jewish qualities. He called Dühring’s claims about the “Judaization of the press” the “ancient accusation of Jewish poisoning of wells” expressed in “modern talk,” and believed Dühring had fundamentally misjudged the Jews: they had survived, Herzl noted in his diary, “1,500 years of inhuman pressure” through the “heroic loyalty of this wandering people to its God.”

Herzl later said his concern about the Jewish Question began when he read Dühring’s book, more than a decade before the Dreyfus affair. At the time, however, Herzl was confident that anti-Semitism would prove a passing phenomenon. He predicted “these nursery tales of the Jewish people will disappear, and a new age will follow, in which a passionless and clear-headed humanity will look back upon our errors even as the enlightened men of our time look back upon the Middle Ages.”

Herzl’s progressive assumptions about the ineluctable progress of European morals, however, would be dispelled—rudely—by something that happened in his own fraternity. It was there, in the heart of the society that had nominally accepted him, that Theodor Herzl would be mugged by reality.

Herzl was among the last three Jews admitted to Albia, reflecting the growing influence of anti-Semitism. On March 5, 1883, the issue came to a head for Herzl after a memorial for the anti-Semitic composer Richard Wagner, held by the League of German Students, of which Albia was a part, and attended by 4,000 students. Several speakers gave, in the words of a contemporary press report, “coarse anti-Semitic utterances.” One of them was a representative of Albia.

After reading the newspaper account of the tirades, Herzl resigned from Albia. He wrote to the fraternity to protest the “benighted tendency which has now become fashionable,” called it a threat to liberalism, and upbraided the fraternity’s failure to oppose virulent anti-Semitism. Affronted by Herzl’s letter, the fraternity instructed him to surrender his insignia immediately. In his reply, Herzl wrote that “the decision to resign has not been an easy one.”

It was also a lonely one: Albia had several Jews among its members and a significant number of Jewish alumni, but only Herzl resigned.

The new anti-Semitism, backed by pseudo-science, would be politicized in the following decade, resulting in opposition to any Jewish participation in public or social life. It was, moreover, fundamentally different from the old religious hatred. Racialized anti-Semitism considered Jews a lower form of life and a biological threat to society that could not be expunged by renunciation of Judaism, embrace of Christianity, or devotion to secular society—nor by demonstrating personal honor through dueling.

Herzl received his doctorate in law in May of 1884 and was admitted to the bar in July. He clerked in the courts for a year, grew bored with the work, and decided to pursue his real interest: playwriting. He would go on to write eleven plays—mostly light comedies—in the decade before he published The Jewish State. Some were produced on stages in Vienna, Prague, Berlin and, in one case, a German theater in New York. But most received disappointing reviews, or did not find a theater interested at all, and Herzl supported himself instead as a journalist. He became an accomplished writer of feuilletons, the stylish, ironic essays that were one of the principal journalistic genres of the time.

In 1889, at the age of twenty-nine, Herzl married Julie Naschauer, eight years his junior, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessman. The marriage was troubled from the start, and as success as a playwright eluded Herzl and his relations with his wife worsened, he suffered from depression. But his feuilletons were widely admired, and in 1891 the Neue Freie Presse—one of Vienna’s most respected newspapers, owned by two assimilated Jewish editors—asked him to become its Paris correspondent.

In Paris, Herzl did not personally experience anti-Semitism, but he remained troubled by the Jewish Question. In 1883, he thought about challenging prominent anti-Semites to duels to demonstrate the honor of the Jewish people. Then he toyed with an idea he thought, as he wrote in his diary, could “solve the Jewish Question, at least in Austria, with the help of the Catholic Church.” He would meet the pope and propose a “great movement for the free and honorable conversion of [young] Jews to Christianity,” in ceremonies “in broad daylight, Sundays at noon, in Saint Stephen’s Cathedral, with festive processions”—in exchange for a papal promise to fight anti-Semitism. (His editors not only rejected the idea, but told him he had no right to suggest it.)

At the end of 1894, Herzl addressed the Jewish Question for the first time in a play that he ultimately called The New Ghetto, which he wrote in what he called “three blessed weeks of heat and labor.” It featured a young liberal Jewish lawyer named Jacob Samuel—a stand-in for the author—who rejects both Jewish materialism and Christian anti-Semitism. Samuel tells a rabbi that while the “outward barrier” of the Jewish ghetto is gone, Jews still had “inner barriers” that “we must clear away for ourselves.” Samuel dies defending Jewish honor in a duel with an Austrian nobleman, and his dying words—the final words of the play—are: “O Jews, my brethren, . . . get out! Out—of—the—Ghetto!”

Despite months of effort, Herzl could not find a theater to stage the play. It would not be produced until three years later, after he had achieved fame as a Zionist, and even then it received only modestly favorable reviews. But after writing it, Herzl told a friend it had opened a “new path” for him—and “something blessed lies in it.” In his diary, Herzl wrote:

I had thought that through this eruption of playwriting I had written myself free of the matter. But on the contrary, I got more and more deeply involved with it. The thought grew stronger in me that I must do something for the Jews.

For the first time I went to the synagogue in the Rue de la Victoire and once again found the services solemn and moving. Many things reminded me of my youth and the Tabak Street temple in Pest.

The following year, Herzl wrote The Jewish State, after an extraordinary experience in June 1895 that both consumed and confounded him. The experience had an unmistakably biblical echo from the book of Samuel—one that Herzl seemed to recognize near the end of his life. It did not involve the trial of Alfred Dreyfus.

Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish captain in the French army, was arrested for providing secret documents to Germany on October 15, 1894, the week before Herzl began writing The New Ghetto. Dreyfus’s four-day closed court-marital ended in late December with a unanimous conviction by the military judges after an hour of deliberation. The court sentenced Dreyfus to life imprisonment and “degradation” (shaming by stripping off his insignia and breaking his sword in public). Two years later, evidence appeared that Dreyfus had been framed to cover up a senior officer’s act of treason. Only in 1898, when Emile Zola published “J’Accuse,” did the affair become the subject of public debate.

In 1894, almost everyone thought Dreyfus was guilty, an opinion Herzl shared—as evidenced by the articles he filed at the time. Herzl never suggested in his contemporaneous press reports that he thought the case had any special significance, nor did he make any reference to it in his diary during June 1895, when his historic transformation into a Zionist occurred. Indeed, in the four volumes and 1,631 pages of his Zionist diaries, covering the nine-year period from 1895 to 1904, there are only twelve brief mentions of Dreyfus, none suggesting Dreyfus played any role in Herzl’s transformation.

What happened to Herzl in June 1895, leading him to reject the assimilation to which he had, to that point, devoted his life, came from a different source.

II. The Chief Actor

In early 1895, Theodor Herzl was living alone in Paris at the Hotel Castille. When he had become the foreign correspondent in 1891, his parents had moved to Paris to be near him. But they disliked the city (and his wife Julie), and they had moved back to Vienna in mid-1894. Herzl’s tempestuous marriage had worsened even further, and in November 1894 Julie had moved back to Vienna with their children.

At the age of thirty-four, Herzl was at a personal crossroads. After his initial, modest success as a playwright, his literary career had declined. He was a journalist and writer of light essays for a respected newspaper, but the work did not strike him as important. Neither his plays nor his journalism had brought him the kind of success he had craved since his student days at the University of Vienna.

A third path, however, would open before him. He was about to become—in the words of his first English biographer, Jacob de Haas—“the chief actor in a world drama of his own devising.” Herzl himself would be mystified by how it happened.

At the end of March 1895, Herzl spent four days in Vienna visiting his family, and he thus witnessed Vienna’s April 1 municipal elections, in which Karl Lueger’s Christian Social Party finished first. Lueger’s movement wasn’t just anti-Semitic; it made anti-Semitism a central plank of its platform. It was the beginning of a process by which Vienna would soon become the first major European city with an overtly anti-Semitic government.

Vienna was Herzl’s home, the capital of the Hapsburg empire, the heart of Central European high culture, where a Jewish population nearly twice as large as that of all of France resided. In Vienna, political anti-Semitism could not be dismissed as “a salon for the castoffs,” as Herzl had described the Paris version. It was scoring significant political success and social influence. Austrian Jews were being accused of polluting the culture they had for a century longed to join, and not simply by a benighted clergy but by politicians and the populace at large, in a democratic election.

Later that year, Herzl would witness Lueger’s party win an even greater electoral victory, recording in his diary that he had personally observed “the hatred and the anger” at a polling station, when Lueger had suddenly appeared and been met with thunderous acclaim:

Wild cheering; women waving white kerchiefs from the windows. The police held the people back. A man next to me said with loving fervor, . . . “That is our Führer.” More than all the declamation and abuse, these few words told me how deeply anti-Semitism is rooted in the heart of the people.

Returning to Paris after his spring visit to Vienna, Herzl was overwhelmed with thoughts about the Jewish Question. They came to him while he was “walking, standing, lying down; in the street, at table, in the dead of night when I was driven from sleep.” He wrote innumerable notes, feeling a mystical compulsion to do so: “How I proceeded,” he recorded in his diary, “is already a mystery to me, although it happened in the last few weeks. It is in the realm of the unconscious.”

At first, Herzl thought he would write a novel about the Jewish situation. The French novelist Alphonse Daudet encouraged him to do so, suggesting it could be another Uncle Tom’s Cabin—a story that might galvanize readers. But Herzl decided instead to draft a letter to Baron Maurice de Hirsch, one of the wealthiest men of the era. Hirsch had been financing settlements in Argentina for Russian Jews after the devastating 1881-82 pogroms. As of 1894, however, the project had proved a failure, producing a total of four colonies and only 3,000 settlers in all. In his letter, Herzl asked Hirsch—twenty-nine years his senior, whom he had never met—to “to discuss the Jewish Question” with him.

Herzl received a polite but dismissive reply, with Hirsch saying he would be in London for the following two months and thus unable to meet Herzl. But Herzl persisted and eventually won an audience on Sunday, June 2, at Hirsch’s palatial residence at 2 rue de l’Elysee.

Herzl prepared 22 pages of notes for the meeting. He began by asking Hirsch to commit to “at least an hour” for the conversation; Hirsch smiled and said, “just go ahead.” Herzl then told Hirsch that pure philanthropy was a mistake—“it debases the character of our people”—and that small-scale colonization was ineffective. Asked what he advised instead, Herzl said the morale of the Jewish people “must first of all be uplifted,” and then they would have to emigrate—whereupon Hirsch promptly terminated the meeting. Herzl had covered only six pages of his notes.

Herzl wrote to the baron the next day, blaming himself for the truncated meeting;

I still lack the aplomb which will come with time and which I shall need in order to break down opposition, shatter indifference, console distress, inspire a craven, demoralized people, and traffic with the masters of the earth.

It was a single-sentence description of what the thirty-five-year-old Herzl would proceed to do over the next eight years.

Shortly after the meeting with Hirsch, Herzl began to keep a diary devoted to his new project. The first paragraph recorded how an all-consuming idea had taken over his life, a “work of infinite grandeur” that “accompanies me wherever I go, hovers behind my ordinary talk, looks over my shoulder at my comically trivial journalistic work, overwhelms me and intoxicates me.” He felt in the grip of something beyond himself, writing in his entry on June 12: “Am I working it out? No! It is working itself out in me.”

In that initial diary entry, Herzl recorded his basic conclusions: (a) that the new anti-Semitism “is a consequence of the emancipation of the Jews”—a reaction by those who perceived the Jews’ new political and economic rights as a threat to their own; (b) that it was a mistake to believe “that men can be made equal simply by publishing a law to that effect;” and (c) that the Jews were still psychologically “Ghetto Jews,” even though they had physically left the ghetto. They needed, Herzl believed, to change their minds—to recover their honor as Jews, to recognize that assimilation in Europe could not succeed, and to embrace a different solution: a new Exodus.

The initial phase of Herzl’s intellectual frenzy ran from June 5 to June 16, with about 150 diary entries during that time, covering 83 pages in printed form. He wrote every day (except Thursday, June 13), composing between eight and 57 entries each day, ranging from single sentences to several pages each.

Herzl’s diary entries would eventually become the basis of The Jewish State, the pamphlet he would publish eight months later. They covered every aspect of a planned and orderly exodus. He outlined new economic and political institutions (“the Jewish Company” and “the Society of Jews,” the forerunners of what would become, respectively, the Jewish National Fund and the Jewish Agency). He proposed large-scale public works, education “for one and all,” creation of inspiring songs (“a Marseillaise of the Jews”), and an enlightened seven-hour workday (with two shifts, so each workday would encompass fourteen hours of work by two sets of workers). He noted that his project had aspects that were not only “moral-political” and “financial,” but “technical, military, diplomatic, administrative, economic, artistic, etc.” He wrote in his diary that he had made plans for them all.

At several points in these entries, Herzl noted both the simplicity of his idea and the magnitude of the concept: “It took at least thirteen years for me to conceive this simple idea. Only now do I realize how often I went right past it.” But its execution would be a world-historical event that would eclipse its predecessor: “The Exodus under Moses bears the same relation to this project as does a [popular play] to a Wagner opera.”

Herzl’s friends and acquaintances worried he had gone mad. He confessed in his diary that he sometimes shared that worry:

During these days, I have more than once been afraid I was losing my mind. This is how tempestuously the trains of thought have raced through my soul. A lifetime will not suffice to carry it all out. But I shall leave behind a spiritual legacy. To whom? To all men. I believe I shall be named among the greatest benefactors of mankind. Or is this belief already megalomania? . . . I think life for me has ended and world history begun.

What possessed Herzl to think he would be leaving a legacy not just to the Jews, but “to all men”? How would he be a player not only in Jewish history, but “world” history? He gave what we may deem his answer in another diary entry the same day:

[T]he Jewish state will become something remarkable. [It] will be not only a model country, . . . but a miracle country in all civilization. . . . The Jewish state is a world necessity. . . . One of the things, perhaps the main thing, that we shall have learned from the civilized nations will be tolerance.

Herzl planned not only to lead the Jews out of Europe, but also to take European liberalism with them; to use it in a land where the Jewish spirit could flourish, as Europe began to destroy liberalism (and eventually itself) with its Jew-hatred. In other words, he wanted not only to save the Jews, but also to save the liberalism he had grown up with, with a single idea: a Jewish homeland that, by its existence, would address the problem of the Jews, solve the problem the world had with the Jews, and avoid the emerging threat to liberalism—all at once.

In mid-June of 1895, Herzl drafted a long address to the Rothschild Family Council, the forum of the other immensely wealthy Jewish family of the time. But he was unable to elicit any interest. He published The Jewish State in February 1896, analyzing anti-Semitism as a “national question” that could “only be solved by making it a political world-question.” It was translated that year from its original German into English, French, Russian, Yiddish, Hebrew, Romanian, and Bulgarian. In an essay in November 1896, entitled “Judaism” (by which Herzl meant something closer to “Jewish identity” than to the religion itself), Herzl supplemented his argument, writing that Judaism was the key to the “lost inner wholeness” of the Jewish people, and that his generation’s distancing from Judaism was the source of its disquiet and disunity.

The Jewish State received a cool reaction from the Jewish Chronicle, then as now the leading Jewish newspaper in London, which printed a long pre-publication summary of it by Herzl in its January 14, 1896 issue. In an adjoining editorial, the Chronicle called it “a scheme hastened, if not dictated, by panic,” saying it was notable for coming from “a man of Dr. Herzl’s type,” one who “does not lay claim to a deep loyalty to Judaism,” and upbraided him for his “dark and discouraging view.” The Chronicle—today a staunchly pro-Israel publication—concluded that “We hardly anticipate a great future for a scheme which is the outcome of despair.”

Undeterred, Herzl organized the First Zionist Congress virtually singlehandedly, and he underwrote its cost out of his own pocket. In mid-1897, however, two months before it was scheduled to begin, he faced a professional crisis that almost derailed the entire effort.

Herzl had decided to start a newspaper devoted to the Zionist movement, calling it Die Welt (“The World”), and he published the first issue on June 4, 1897. When the publishers of the Neue Freie Presse—both vehement anti-Zionists—got wind of this endeavor, they urged him to shut it down, complaining that it was a source of “great embarrassment” to them. But despite their repeated requests, Herzl remained, as he wrote in his diary, “inflexible,” even with the knowledge that it might get him fired.

Proceeding in the face of opposition from his employers carried both professional and personal risks for Herzl. He owed much of his reputation to the Neue Freie Presse, with its wide readership not only in Vienna but throughout Europe. Without that position, Herzl might jeopardize both his personal finances and his intellectual influence at the same time. But he was undeterred.

The opposition to his Zionist Congress came not only from his employer but from various elements of the Jewish community. Herzl had planned to hold the Congress in Munich, a city convenient for delegates to reach, with a significant Jewish population and many kosher restaurants. But the Munich Jewish community protested, and Herzl and his organizing committee had to shift the location to Basel.

Herzl worked simultaneously on the Congress and Die Welt, in addition to his Neue Freie Presse work, “exhausting all my strength.” The amount of work, he wrote in August, has been “enormous.” On August 23, with the Congress only a week away and the outcome still uncertain, he wrote in his diary that if it did not produce serious results, he would “withdraw from the campaign and confine myself to keeping the flame alive in the Welt.” Herzl was also haunted by the fear that he might die before he could finish the task he felt destined for, and for good reason: he had a heart condition that he had disclosed to no one outside his family.

The First Zionist Congress attracted 204 delegates from twenty countries and regions. About half came from areas within the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires (where 80 percent of the Jews in the world then lived). The rest came from Germany, Italy, Switzerland, England, France, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, Serbia, Belgium, Sweden, Palestine, and the United States.

The Congress lasted three days and adopted the platform that would govern Zionist efforts for the following twenty years, culminating in the Balfour Declaration, defining the goal of Zionism as “establishing for the Jewish people a publicly and legally assured home in Palestine.”

Herzl insisted the delegates dress in formal attire to reflect the dignity of the event, and he hung a flag in the conference hall with a white field (symbolizing a new Jewish future), two blue strips (making it resemble a tallit), and a Star of David at the center (reflecting the centrality of Jewish identity to the movement). Herzl had spent considerable time working on the flag with the Russian Jewish businessman-turned-Zionist activist David Wolffsohn, since he viewed the flag as extremely important. In his letter to Baron Hirsch in 1895, he had written, “Men live and die for a flag; it is indeed the only thing for which they are willing to die. . . . Visions alone grip the souls of men.”

Herzl’s appearance on the first morning of the Congress caused, as Michael J. Reimer notes in his annotated translation of the official proceedings, “prolonged and forceful clapping, cheering, foot-stomping, and cane-pounding.” In his address, Herzl described the “pain and anger” the Jews saw in the renewal of the “old hatred” in modern times. He then discussed what he saw as the critical first ingredient of Jewish nationalism:

We have, so to speak, come home. Zionism means a returning home to Jewish identity before the return to the country of the Jews. . . . A people can only be helped by itself; and if it cannot do that, then it is quite beyond help. We Zionists want to arouse our people to self-help.

Herzl told the delegates the goal was public legal guarantees of “the historic homeland of the [Jewish] nation, precisely because it is the historic homeland.”

On the final evening session of the Congress, Arthur Cohn, the thirty-five-year-old Orthodox rabbi of Basel, gave his address. He received, according to the official minutes, “a thunderous welcome.” Rabbi Cohn praised Herzl, declaring that “his heart swells with deep emotion” after hearing the speeches. But Cohn also expressed his concern that, “if the Jewish state were to arise now, its party leadership, which we know does not honor [religious Jewry’s] views, would attack the Orthodox.” He asked for some clarification about this issue.

Herzl responded by thanking him, “our erstwhile opponent,” for “the frankness of his request,” and told him: “I can assure you, Zionism intends nothing that might violate the religious conviction of any orientation within Jewry,” which produced another round of “thunderous applause.”

Herzl had created an atmosphere—out of nothing—that made the delegates feel that they were the National Assembly of a Jewish state. One of the delegates, in a letter written soon after the Congress, observed that “attitudes toward Zionism have changed completely. This is true of the rabbis, the intelligentsia, and the community as a whole.”

That Zionism had transformed not only the delegates, but Herzl himself, is apparent in a tale he published in Die Welt later that year, about an artist who had long ignored his Jewish roots and was living comfortably when “the age-old hatred re-asserted itself under a fashionable slogan.” The artist’s soul is a “bleeding wound,” but he experiences a “mysterious affection” for Jewish identity as the solution to Jewish suffering. A “strange mood came over him”—the memory of Hanukkah as a child. He buys a menorah and tells his children about the Maccabees. The “great radiance” of the menorah, reflected in their eyes, satisfies his “longing for beauty.” The artist sees the week-long candle-lighting as “a parable for the kindling of a whole nation”:

First one candle; it is still dark, and the solitary light looks gloomy. Then it finds a companion, then another, and yet another. The darkness must retreat. The young and the poor are the first to see the light; then the others join in, all those who love justice, truth, liberty, progress, humanity, and beauty. When all the candles are ablaze everyone must stop in amazement and rejoice at what has been wrought.

Scholars and biographers have viewed “The Menorah” as a charming autobiographical story, reflecting Herzl’s return to his Jewish identity, expressing what he had achieved in only two years. Herzl himself viewed it as reflecting something greater than his personal evolution: he told Jacob de Haas it represented his ability to see in the Menorah the “brilliantly lit-up new Jerusalem,” while others saw only melted wax.

Perhaps in retelling the story of Hanukkah, Herzl was also recalling a part of Tancred—the Disraeli novel from which he had chosen his fraternity name—which devoted an entire chapter to Sukkot, described by the Jewess Eva as “one of our great national festivals,” the “celebration of the Hebrew vintage, the Feast of Tabernacles.” The novel noted:

The vineyards of Israel have ceased to exist, but the eternal law enjoins the children of Israel still to celebrate the vintage. A race that persist in celebrating their vintage, although they have no fruits to gather, will regain their vineyards.

In 1899, the wife of a South African diplomat interviewed Herzl and, in an article based on that interview, wrote that, listening to his “warm, expressive voice” and “vibrant, moving words,” she was reminded of that passage from the novel.

In two years, Herzl had taken his ideas to the major Jewish philanthropic families (who refused to support them); to the Jewish intelligentsia (who generally dismissed them); and then to the Jewish public (who endorsed them in numerous countries). He had established a Zionist Congress that formally adopted the goal of a Jewish state.

But, as we will see presently, even greater challenges were yet to come.

III. The Transformation of the Jews, and of the Jewish Question

It is frequently noted that Herzl did not originate the idea of a Jewish state—he said so himself in the opening sentence of his book. His contribution to Jewish political thought was rather his understanding of the intellectual transformation necessary to achieve statehood.

He captured his approach in an epigram—“If you will it, it is no dream” (in the original German, “no fairy tale”). A Jewish state did not exist simply because previous thinkers had thought it. Herzl’s fundamental insight was that, before the Jewish people would be ready for a state, they would first have to change their character—through a process not unlike what their ancestors had undergone in the desert with Moses—and revive their will as a people.

Herzl’s second principle was that it was necessary to convert the Jewish Question from a philanthropic matter, supported by the wealthy Jewish families of the era, to an issue of international relations to be faced by the world.

Ahad Ha’am, the most prominent Hebrew-language essayist of the time, and a leader of the Russian “Love of Zion” movement that Pinsker had helped to found, attended the First Zionist Congress as a skeptical observer—and did not come away swayed. Shortly afterwards, he wrote an essay asserting that a Jewish state was “a fantasy bordering on madness.” He argued instead for building in Palestine a “center for the spirit of Judaism” that would “breathe new life into the Diaspora.” The “secret of our people’s persistence,” he wrote, was that “the prophets taught to respect only spiritual power, not to worship material power.” In contrast to Herzl’s slogan, Ahad Ha’am endorsed one drawn from the book of Numbers (24:17): “I shall see it, but not now; I shall behold it, but not nigh.”

It was the beginning of a fierce clash between the “cultural Zionism” of Ahad Ha’am and the “political Zionism” of Herzl—between those who wanted a spiritual center to save Judaism, and those who wanted a state to save the Jews. There would eventually be other types of Zionism—religious Zionism, Chaim Weizmann’s practical Zionism, Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionism, and of course Labor Zionism—each seeking a Jewish home but on different ideological grounds. The sheer breadth of these varying approaches made Zionism an ideology that could attract Jews from left to right. The intellectual competition between them sharpened Zionism as a whole.

Herzl’s insistence on seeing Zionism through the lens of international relations stemmed from his realization that—as he told the Second Zionist Congress in 1898—Palestine was “by reason of [its] geographical position, of immense importance to the whole of Europe.” To Britain, a Jewish state could be a gateway to India; to the Ottoman empire, a way to secure international re-financing of debilitating debt; to Russia, a solution for its large and rebellious Jewish population; and to Germany and Austria-Hungary, a strategic asset in their competition with the other empires.

Finally, Herzl connected the nationalism of the Jews to the wave of nationalist efforts of others: as he told Lord Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild (head of the English branch of the family) in 1902:

In our own time, Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, Bulgarians have established themselves [in independent states]—and should we be incapable of doing so? Our race is more efficient in everything than most other peoples of the earth. This, in fact, is the cause of the great hatred. We have just had no self-confidence up to now. Our moral misery will be at an end on the day when we believe in ourselves.

In the years following the First Zionist Congress, Herzl began to establish a Jewish national bank, went to Palestine in 1898 to meet the Kaiser in Jerusalem, met with the president of the Austrian ministry, had an audience with the grand duke of Baden, met with Sultan Abdul Hamid II in Constantinople (twice), and convened the Congress annually in Basel—except in 1900 when the Congress met in London as part of an effort to engage Britain. In 1902, Herzl testified in London before the British Royal Commission on Alien Immigration, which had been established to investigate the influx of Jewish refugees from Russia and Romania. The British Jewish population had risen to about 100,000, prompting alarm about the continuing inflow.

Three days before his testimony, Herzl met privately with Lord Rothschild, who sat on the Commission and who saw Zionism as a threat to the acceptance of British Jews as loyal subjects. He asked Herzl to support the idea of Jews as Englishmen in his testimony—and Herzl flatly refused, insisting that he would “simply tell them what frightful misery prevails among eastern Jewry, and that the people must either die or get out.” A stunned Rothschild asked Herzl not to tell the Commission that, because the government was already worried about excessive Jewish immigration. Herzl characteristically dug in his heels.

Three days later, Herzl told the Commission “the state of Jewry is worse today than it was seven years ago when I published my pamphlet;” that in Eastern Europe—where most of world Jewry lived—things were “becoming worse and worse day by day;” and that the solution was “recognition of Jews as a people, and the finding by them of a legally recognized home,” so they would arrive “arrive there as citizens . . . because they are Jews, and not as aliens.”

During the questioning, Lord Rothschild asked Herzl to define what he meant by “Zionism.” He asked whether it was a “movement to re-establish a Jewish state in Palestine, or whether . . . you simply mean that some great endeavor should be made to colonize some part of the world entirely with Jews.” Herzl knew it was a loaded question, and he responded by telling the Commission it was both.

Herzl’s answer reflected the dual nature of Zionism as of 1902. It had both an ultimate objective (a Jewish state in Palestine) and an urgent need (an immediate refuge for Jews under existential threat). It was not clear if those goals could be pursued together, or whether at some point they would necessitate a choice. Herzl was trying to keep both options open. He informed the Commission that he received “30 or 40 letters” every day from Russia, where Jews lived in “a permanent state of misery [because they] cannot better their condition; they cannot go into another town to find work; they are under a constant pressure,” with no one “sure of his life tomorrow,” living “in a perpetual fear with the madness of persecution.” In Romania, he testified, more than 37,000 starving Jews had petitioned the First Zionist Congress for help, and their conditions had not improved; in Galicia, about 700,000 Jews were in “very deep misery,” living in cramped quarters, sometimes four families in the four corners of a single room. The worst slums in London were a comparative “paradise.”

Herzl’s testimony was eloquent, but he felt he had performed poorly, confiding to his diary that he had spoken and understood English badly. The next day he met the chairman of the Commission, Lord James of Hereford, hoping to “repair the bad impression which I felt I had made.” Lord James told him a Jewish colony somewhere could only be achieved with the help of Lord Rothschild, and so Herzl met with Rothschild again the next day, and promised to send him a plan for an immediate Jewish colony. He suggested Cyprus, while emphasizing he would not give up on the long-term goal of Palestine.

On July 21, 1902, Herzl wrote again to Lord Rothschild, attempting to put the Zionist case in terms of British interests, telling him “you may claim high credit from your government if you strengthen British influences in the Near East by a substantial colonization of our people at [a] strategic point.” He emphasized that immediate action was necessary, because if the opportunity were missed:

Then it will turn out that we Jews, we smart but always outsmarted Jews, will once again have missed the boat. The thing can now be done: big and quick, through the [land company] of which I sent you a general outline.

Lord Rothschild replied on August 18, 1902, not only rejecting Herzl’s plan but telling him that he “view[ed] with horror the establishment of a Jewish Colony pure and simple.” All it would mean, he said, was relief for a few thousand Jews; he preferred instead that Jews “live amongst their Christian brethren.”

In his response, Herzl countered that the Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, and Bulgarians had all recently established themselves as nations and there was no reason the Jews could not do so as well.

Two months after his testimony, Herzl began discussions with (as he described him in his diary) “the famous master of England, Joe Chamberlain.” Joseph Chamberlain, the father of the future prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, was Britain’s colonial secretary and the most influential member of the cabinet. Herzl wanted him to dedicate some territory for a Jewish colony within Britain’s far-flung empire.

On October 23, 1902, Herzl spent an hour with Chamberlain, writing afterwards that “my voice trembled at first, which greatly annoyed me,” but that after a few minutes “I was able to talk calmly and incisively, to the extent that my rough-and-ready English permits it.” Addressing Chamberlain’s “motionless mask,” Herzl “presented the whole Jewish Question as I understand it and wish to solve it.”

Chamberlain told Herzl he sympathized with Zionism. Herzl asked for territory either in sparsely populated Cyprus, or in El Arish on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, which was largely vacant. Either location, he told Chamberlain, would be “a rallying point for the Jewish people in the vicinity of Palestine.” The next day, Herzl sent a memorandum, outlining a plan for a Jewish colony in El Arish. Chamberlain sent it to Lord Evelyn Cromer, the consul-general in British-ruled Egypt. Herzl noted in his diary that he had so worn himself out that his heart had been “acting up in all sorts of mysterious ways.” But he thought his exhaustion might presage something historic: “Is it possible that we stand on the threshold of obtaining a—British—charter and founding the Jewish state?”

Lord Cromer responded in a long letter on November 22, 1902, noting various political and other difficulties but urging further study. Herzl and the British authorities reviewed the issue over the following months, and Herzl commissioned a draft agreement from the law firm of David Lloyd George. But eventually the Egyptian administration objected, and the project was dropped in mid-1903.

The collapse of Herzl’s efforts for El Arish coincided with a horrific pogrom in Kishinev (now Chisinau, Moldova), about 90 miles northwest of Odessa. Kishinev was not a remote shtetl; it was Russia’s fifth-largest city, a provincial capital with 110,000 residents, about one-third to one-half of them Jewish.

The two-day rampage in Kishinev began on April 19, 1903—four months before the Sixth Zionist Congress was scheduled to convene. Forty-nine Jews (including children) were murdered; women were raped; injuries ran into the hundreds; about a thousand homes were destroyed or damaged. On April 26, in its Sunday edition, the New York Times reported, “Scores of Jews Killed: Details of the Anti-Semitic Riots . . . Add to the Horrors”.

Jacob Kohan-Bernstein, director of the Zionist Organization’s press department, lived in Kishinev, and he used his contacts in the Western media to publicize the pogrom. In the United States, the atrocities received significant press coverage: there were demonstrations in 27 states; 80 newspapers published more than 151 scathing editorials; senators, congressmen, and mayors gave public addresses. The Hearst newspapers sent Michael Davitt, a respected Irish-born journalist, to Kishinev to interview survivors and he published vivid reports.

The B’nai B’rith prepared a formal petition to the tsar, signed by 12,544 prominent American political figures, publishers, and Christian clergy, and asked President Theodore Roosevelt to submit it to Russia. Secretary of State John J. Hay at first rejected the idea, but the president eventually directed the U.S. ambassador in St. Petersburg to seek an audience with the Russian foreign minister to deliver the B’nai B’rith petition and say the “cruel outrages . . . have excited horror and reprobation throughout the world.” But the Russian government refused to receive the petition, and the Roosevelt administration dropped the issue.

It was Theodor Herzl who took Kishinev beyond protest and petition.

On May 8, 1903, he published an article in Die Welt promising that what had happened to “our brothers in distant Bessarabia” would not be forgotten. He vowed that, unlike with previous pogroms, there would be an effective response, and not merely an outpouring of public sympathy.

Herzl had been seeking to meet with the Russian government since 1896, but his requests had been rebuffed. In the wake of Kishinev, he wrote again on May 19, 1903 to the powerful Russian minister of the interior, Vyacheslav Plehve, requesting support for an “organized emigration” of Jews from Russia. Plehve was widely known as harshly anti-Jewish. Shortly after the pogrom, the Times of London published a letter—shown decades later to have been a forgery—from Plehve to the Kishinev police before the pogrom, signaling government support for the coming violence. Many Zionists thought it was shameful that Herzl would consider meeting with such a man.

But Herzl saw that Plehve and he had a mutual interest: Plehve didn’t want Jews in Russia, and Herzl wanted them to leave, with a place to go. He believed Russia could influence the sultan to permit a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and he knew Plehve needed his help to improve Russia’s image in the West, since Kishinev would be discussed at the upcoming Zionist Congress, with the international press in attendance.

Plehve and Herzl met on August 8, 1903, and Plehve agreed that Jewish emigration was the answer. He promised to make an “effective intervention” with the sultan for a charter in Palestine and to permit Zionist activity in Russia. On August 12, Herzl received a formal letter from Plehve, stating that Russia favored the creation of “an independent state in Palestine.” Plehve told him the letter had been reviewed by the tsar and thus was an official declaration of the Russian government. Herzl published it in Die Welt and considered it extremely important: it was the first formal governmental endorsement of a Jewish state, and he could use it as a diplomatic lever elsewhere.

On August 14, 1903, the second major endorsement of a Jewish homeland came when the British made a formal offer of land in East Africa for Jewish settlement. The name of the settlement was to be “New Palestine.” Herzl thought the British offer was another important step forward: he told his ally, the major European intellectual Max Nordau, that “we have, in our relationship with this gigantic nation, acquired recognition as a state-building power.” But most importantly, there had to be, Herzl thought, “an answer to Kishinev, and this is the only one” immediately available. He arranged for a draft charter to be prepared by David Lloyd George’s firm.

At the Congress in August, now with 592 delegates in attendance, Herzl presented his two great diplomatic triumphs—the official recognition of Zionist goals by both Britain and Russia, two of the world’s largest empires. He expected to receive praise for his efforts. But the sizeable Russian delegation reacted in a fury, believing Herzl had been used by Plehve and that the British offer was a dangerous diversion from Palestine. Some accused Herzl of a willingness to abandon the Promised Land altogether.

Max Nordau urged the delegates to view East Africa as a Nachtasyl, a “shelter for the night,” offered by the greatest power on earth. It would be irresponsible, he argued, not to form at least an exploratory delegation. The delegates ultimately approved a committee to visit the site and report to the next Congress, but the resolution passed by only a plurality: 295 in favor, 176 against, 143 abstentions. Most West European delegates voted yes, while most from Russia and Poland voted “no.” A journalist covering the Congress wrote that the vote was greeted by “cheers and groans.” The entire Russian delegation stormed out. Herzl eventually persuaded them to return, but they had sullen expressions on their faces.

In his concluding address—the last he would ever deliver to a Zionist Congress—Herzl praised it as “our first institution, and I trust it may ever remain the best, highest, and most worthy until we transplant it to the beautiful land of our fathers, the land which we need not explore to love.” He reminded the delegates that “[w]e cannot always follow the crow’s flight” and “if it were possible to proceed by the straight cloud-path, no leader would be required.”

Herzl then said he wanted to offer the delegates an assurance. He raised his right hand and uttered in Hebrew the pledge from Psalm 137: “If I forget thee O Jerusalem may my right hand forget its cunning.” The gesture, the sentence, and the rendition in Hebrew produced deafening applause.

After the Congress ended, Jacob de Haas escorted Herzl to the train station, where Herzl embraced him and said the next Congress would be “the Congress of the Exodus.” In his diary, Herzl wrote that he had told Nordau that if he lived until the next Congress, “I will by then either have obtained Palestine or have recognized the impossibility of all further effort.” In the latter case he would “retire from the leadership and advise the creation of two bodies, one for East Africa, one for Palestine,” and let the delegates decide which way to go.

The rift between Eastern and Western Zionists continued after the Congress, and Herzl was castigated in the press for the East Africa proposal. The Jewish Chronicle asked editorially “whether the history of Israel was . . . to end in an African swamp [with] the suggestion that Jews are to be vomited forth from Western lands and banished into barbarism.” On September 3, 1903, twenty-seven-year-old Chaim Weizmann published a scathing attack on Herzl in the Warsaw Hebrew newspaper Hatsofeh (“The Observer”). He asserted that Herzl was not really a Jewish nationalist, but merely a “promoter of projects” who, in suggesting East Africa, ignored the “psychology of the people and its living desires.”

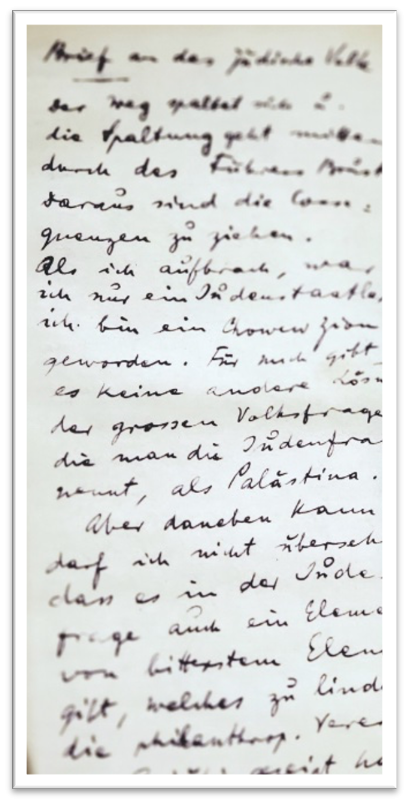

Herzl had left Basel in August exhausted from the extraordinarily emotional debate. “Palestine is the only land where our people can come to rest,” he wrote in his diary, “but hundreds of thousands need immediate help.” By November 1903, he had made no more progress in his diplomatic efforts to persuade the Ottoman empire to permit a Jewish home in Palestine. Given the continuing rift in the Zionist movement, he concluded he could no longer serve as its head. On November 11, 1903, he drafted an impassioned “Letter to the Jewish People,” resigning as president of the Zionist Organization.

Herzl’s letter began with this sentence: “The path splits, and the split goes straight through the leader’s heart.” He had been only a “Jewish statist” at the beginning, he wrote, but he had eventually become a Ḥovev Tsion (a “Lover of Zion”), and yet he remained torn between the ultimate goal of a home in Palestine and the immediate goal of a Jewish refuge wherever possible:

For me there is no other solution but Palestine for the great national question which is called the Jewish Question. But I cannot and must not overlook the fact that the Jewish Question also contains an element of bitter distress which the philanthropic organizations have proved incapable of alleviating.

To bring relief to this distress, he needed land, and the only land on offer was in East Africa.

Herzl concluded his resignation letter with an evaluation of what he believed he had achieved in his six years of leadership:

In accordance with my modest energies I have created some instruments for the awakened Jewish people. I shall certainly not leave embittered or dissatisfied. . . . I was richly rewarded far beyond what I merited and deserved, by the love of my people—a measure of love such as has seldom been bestowed upon individuals who had a far greater claim to such love than I did. I am not owed anything. The Jews are a good people, but unfortunately also a profoundly unhappy one. May God continue to help them.

Herzl never sent the letter. The handwritten draft was found among his papers eight months later, after his death. It was not published until 1928. Herzl remained president of the Zionist Organization in 1903, even as his health deteriorated and further diplomatic success eluded him. In his last eight months, he met with the pope, the king of Italy, the Austrian foreign minister, and others, before dying of a chronic heart condition on July 3, 1904.

In a January 24, 1902 diary entry, Herzl wrote that “Zionism was the Sabbath of my life,” and he credited his accomplishments to his principled pursuit of his idea:

I believe that my effective leadership is to be attributed to the fact that I who, as a man and a writer, have so many faults and have been guilty of so many mistakes and follies, have been in this matter of Zionism pure of heart and wholly unselfish.

At the beginning of 1904, concerned about Herzl’s health and finances, some of his Zionist associates had offered to arrange an annuity for him, but Herzl refused, telling David Wolffsohn, “what about my self-respect? Why would I accept money [to] act according to my convictions?” Israel Zangwill assured him it would be kept secret, to which Herzl responded, “You say no one would know. One person would know. I would know.”

Herzl died in poverty. His wife and their three children would depend on financial support from the movement after his death. Julie died in 1907 at the age of thirty-nine; the three orphaned Herzl children led difficult lives and died at young ages, one by drug overdose, one by suicide, and one in the Holocaust.

Herzl did not live to see the resolution of the East African controversy that had split his heart. At the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905, the delegates formally rejected the East Africa idea. Twelve years later, however, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration, and many historians believe Herzl’s efforts involving important British figures—including Arthur Balfour (prime minister at the time of the East Africa negotiation) and David Lloyd George (his lawyer and later the prime minister at the time of the Balfour Declaration)—set the essential stage for the seminal British endorsement in 1917 of a Jewish national home in Palestine.

Was there a divine element in Herzl’s emergence on the world stage? The question is of course unanswerable, but Herzl’s story bears a certain resemblance to that of the prophet Samuel—one that may have struck Herzl himself, as his health began to decline precipitously in late 1903 and early 1904.

In the opening chapter of the book of Samuel, a barren Hannah prays for a child, pledging to dedicate him to the Lord. Her prayer is granted; she names him Samuel and sends him to live with the high priest Eli. Late one night, Samuel hears someone calling his name; he goes to Eli and says, “Here I am.” Eli tells him he didn’t call. Samuel goes back to sleep; the Lord calls again; Samuel goes to Eli, and Eli again says he didn’t call. When it happens yet again, Eli recognizes it is the Lord calling Samuel, and he advises Samuel to say, “Speak, Lord, for Your servant is listening.” The Lord calls again; Samuel says he is listening; and the Lord tells him: “I am about to do something in Israel that will make the ears of everyone who hears of it tingle.” Through Samuel, the Lord will prevent Eli from passing the priesthood to his sons, and eventually crowns Saul the first king of Israel.

Samuel’s story played a role in a dream Herzl had when he was twelve years old. He recounted it, about six months before his death, to his Zionist colleague, Reuben Brainin. In his dream, a majestic old man (the “King-Messiah”) had taken him into the clouds, where they met Moses. The King-Messiah told Moses, “It is for this child that I have prayed,” and tells Herzl, “Go, declare to the Jews that I shall come soon and perform great wonders and great deeds for my people and for the whole world.” Herzl told Brainin he had never disclosed the dream to anyone.

As a child preparing for his bar mitzvah, Herzl may have known the stories of both Samuel and Moses and subconsciously combined them in a dream. His recollection and disclosure, three decades later, reflected not self-importance but rather a certain wistfulness: his health was failing; his heart had been broken at the Sixth Zionist Congress; he was eight years into his project and a Jewish state was nowhere on the horizon; the way forward was unclear and he was thinking of stepping down. He had already drafted his resignation letter. But through him, the ears of the Jewish people had tingled.

Perhaps the story of Samuel can serve as a parable for Herzl’s life: he thought he had a calling as a playwright, but he was wrong; then he thought his calling was as an essayist and reporter, but writing gave him only a small success. Then, in June 1895, he was possessed by an all-encompassing idea—one that came from a mysterious source, like a voice in the night, that he could not identify. But on his third try, Herzl had found his calling. Or perhaps his calling found him.

Herzl’s life and his achievements were of biblical proportions. As a writer, as an institution builder, and as a diplomat, he bore on his shoulders the weight of the Jewish future. At the appointed hour, his prophecy, written on the final page of The Jewish State, miraculously came true:

I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again. . . . The Jews who wish for a state will have it. . . . And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity.