On February 10, 1896, just days before The Jewish State was published, Theodor Herzl wrote in his diary about another pamphlet he had recently discovered. He observed that it was very similar to his own book, and it was “a pity that I did not read this work before my own pamphlet was printed. On the other hand, it is a good thing that I didn’t know it—or perhaps I would have abandoned my own undertaking.” It is surprising that Herzl, a man who devoted his life to the Zionist cause, might have been so easily deterred from publishing The Jewish State and spearheading the Zionist movement.

The pamphlet, Autoemancipation!: A Call to His Brethren from a Russian Jew, was written by a physician named Leon Pinsker, after a wave of pogroms swept through southern Russia. Although Pinsker’s intended audience—well-to-do West European Jews with the resources and abilities to organize a national revival—barely noticed the book, it had an enormous impact on his fellow East Europeans. More than fifteen years before the First Zionist Congress, it would become a manifesto for the reconstitution of Jewish life in the Land of Israel. And it is every bit as essential to the story of the creation of a Jewish state as Herzl’s own work.

The history of Zionism typically begins with Herzl at the Dreyfus trial, which supposedly awakened him to the dangers of anti-Semitism, leading him to question his assimilationist assumptions and embrace the idea of a Jewish state. He then founded the Zionist Organization at the 1897 Basel conference, which would pave the way—after some hiccups and distractions—for the Balfour Declaration in 1917, and for Israel’s independence three decades later.

The trouble with this common story is that by the time Herzl arrived on the scene in Western Europe, Jews from Eastern Europe had already been migrating to Palestine in small but significant numbers for nearly a decade and a half. Migration and settlement were overseen by a loose confederation of local organizations known collectively as Ḥovevei Tsiyon (Lovers of Zion) and led by Pinsker. Even responsible historians, aware of the general faults of the potted narrative, tend to reduce this early iteration of Zionism to mere prologue, if not simply a failed first attempt. Walter Laqueur devotes eight pages of his nearly 600-page A History of Zionism to Ḥovevei Tsiyon, relegating it to a chapter aptly titled “The Forerunners.” David Vital’s magisterial three-volume history of Zionism gives more attention to Ḥovevei Tsiyon, but nonetheless makes clear that it is a precursor to the real thing.

This attitude is not unfounded. The Ḥovevei Tsiyon movement was beset by internal strife and lack of funds. Its devotees were mostly intellectuals who arrived in Ottoman Palestine entirely unprepared for the sort of agricultural work they dreamed of doing. Between 1881 and 1905, about half of the Jewish settlers are thought either to have returned to Russia or sought greener pastures in America. Judged by the standards of Herzl’s political strategy, which aimed to get support for the creation of a Jewish state from the Great Powers of Europe or the Ottoman empire, these settlements accomplished nothing.

Nevertheless, Autoemancipation! played a crucial and enduring role in the quest to attain a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. Its core idea is one that is crucial to the Zionist ethos: that Jews must take responsibility for their own fate, and cannot rely on the beneficence of Gentile regimes. For all the similarities Herzl noted between Pinsker’s manifesto and his own, it is only Pinsker’s that makes this idea of self-reliance its centerpiece. And that is why, where Herzl sought legitimacy from external sovereigns, Pinsker by contrast sought to establish facts on the ground, and so he presided over the first coordinated effort to reestablish a Jewish presence in the Land of Israel. Together Pinsker and Ḥovevei Tsiyon began a complementary alternative to Herzlian Zionism that persisted right up to the founding of the state, and whose lessons remain relevant today. It was the productive tension between the two approaches that made the accomplishment of 1948—75 years ago this month—possible.

I. Pinsker Himself

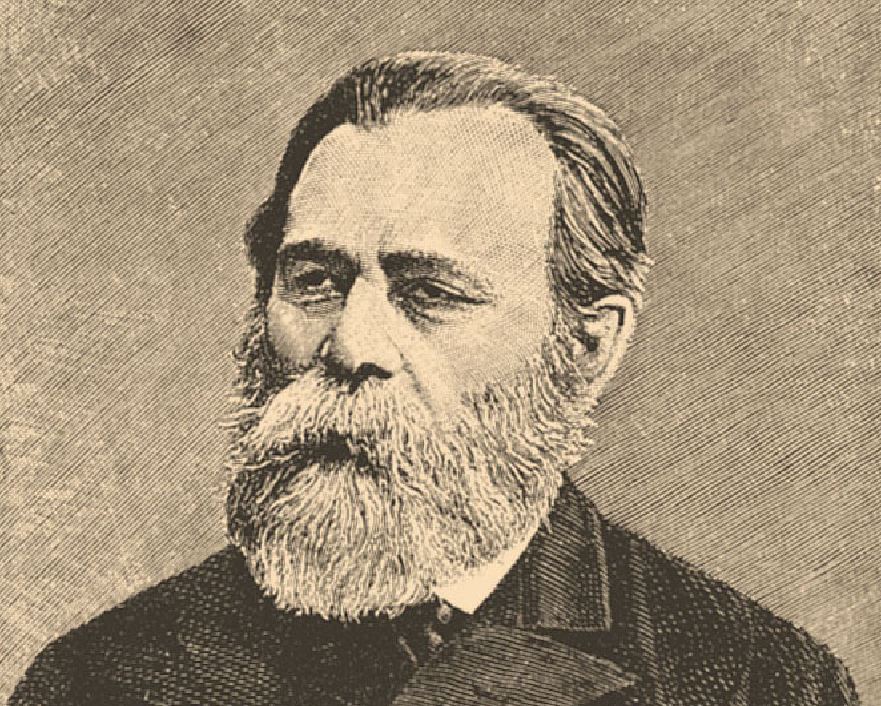

To understand this forgotten part of the Zionist story, we must begin with Pinsker himself. Pinsker was born in 1821 in the Polish town of Tomaszów, and was a small child when his father, Simḥah Pinsker, moved the family to the cosmopolitan port city of Odessa. A maskil, or devotee of the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah), Simḥah was a well-known scholar of the Karaites—a Jewish sect originating in the early Middle Ages whose rejection of the Talmud and other rabbinic traditions no doubt appealed to Haskalah sensibilities. In the 19th century, Odessa was a haven for maskilim and reformers eager to get away from the strict traditionalism of the shtetl. Simḥah helped to found the city’s first modern Jewish school, in which young Leon received his elementary education and learned the Russian language. There Simḥah taught the Prophets and Writings (sections of the Hebrew Bible usually neglected by more traditional schools), along with Hebrew grammar and practical bookkeeping skills. German—seen as a language of Western civilization—was spoken in the Pinsker household.

Thus, at a time when most Russian Jews spoke Yiddish, could read and write Hebrew to varying extents, and knew only enough of the local language (often Polish or Ukrainian) to conduct everyday business activities, young Leon was fully literate in two high-status non-Jewish languages. He was also shaped by Odessa’s laissez-faire atmosphere, where Jews interacted relatively freely with their Gentile neighbors, and were often lax in their religious observance. As early as the 1830s one could find Odessa’s Jews attending the opera alongside Russians, something that would be unseen for decades elsewhere in the empire. It is not for nothing that Jewish traditionalists would say “the fires of hell burn for seven miles around Odessa.”

Armed with his modern education, Leon became one of very few Jews permitted to study medicine at the University of Moscow. He returned to Odessa after his graduation, and would work there as a physician for much of his life. Though he maintained an awareness of his Jewish background and concern for Jewish affairs, in his daily life Pinsker spoke Russian, read Russian literature, and interacted with non-Jewish Russians on a regular basis. He believed that all Russian Jews should do the same. Anti-Semitism, maskilim of Pinsker’s ilk believed, was a product of the Jews’ foreignness and would fade as Jews integrated themselves into Russia society and showed their loyalty to the regime. Pinsker did the latter by serving as a military doctor during the Crimean War (1853–1856).

By the war’s end, the reactionary Tsar Nicholas I, whose policies toward Jews were characterized by bigotry and suspicion, had died. Alexander II, his son and successor, was by contrast a reformer, who in the 1860s freed the serfs, modernized the legal system, reduced censorship, and loosened some of the discriminatory legislation concerning Jews. Filled with optimism of the era, maskilim became increasingly confident that they would soon attain the sort of legal equality enjoyed by their coreligionists in the West.

This era saw the flourishing of the Russian Jewish press, of which Odessa became a major center. Pinsker contributed regularly to the Russian-language Jewish newspapers, often anonymously. In addition, he was one of three founders of the Odessa branch of the Organization for the Promotion of Enlightenment among the Jews, which championed secular education and knowledge of Russian in the liberal integrationist vein. But the hopefulness of Pinsker and his fellow maskilim would soon be shattered.

In 1871 a pogrom broke out in Odessa. This violent outburst, and the widespread (but mistaken) belief in the Russian state’s complicity, undermined liberal Jews’ faith in progress. The publishing and organizational activity of Odessa’s Jewish intelligentsia slowed, and a few of its members began questioning their assumptions about the Jewish future in Russia. Pinsker for his part went silent, and very little is known about what he was thinking during these years. It would take another, more severe, eruption of anti-Semitic violence to shake him out of this silence.

In April 1881, radical members of a revolutionary group assassinated Alexander II. A Jewish woman named Hesia Helfman was a member of the cell that carried out the attack. This piece of information combined with widely held anti-Semitic beliefs and rapidly spreading rumors to provoke a wave of pogroms, most of which took place in what is now Ukraine. These continued into 1882 and caused millions of rubles of property damage. In comparison to later anti-Jewish outbursts, relatively few lives were lost, but at the time the violence was shocking, even in a country where Jews experienced pervasive social and legal discrimination. For maskilim like Pinsker, however, the most disturbing feature of the pogroms was not the violence itself, but rather the response from educated and supposedly progressive Russians. Rather than express sympathy or indignation, Russian Gentile liberals generally responded with indifference. Worse still, the radicals cheered on the violence, seeing attacks on Jews by the urban working class as a legitimate assault on the oppressive bourgeoisie.

The pogroms became the moment that many educated Russian Jews were “mugged by reality,” to use Irving Kristol’s famous phrase. Russians’ unwillingness to help the Jews in their time of need led maskilim like Pinsker to question their most basic assumptions. Any solution to the Jews’ ills that relied on the goodwill and acceptance of Russian intellectuals and the Russian state, much less the uneducated Russian masses, was chimerical. Instead of seeking to integrate into a non-Jewish world that would never accept them, Jews needed to chart their own path. Jews needed a collective national movement, rather than a quest to win individual rights. In the summer of 1882 Leon Pinsker put these ideas on paper and argued that the only solution to the Jewish plight was the creation of an independent state. This was the pamphlet Autoemancipation!

II. Autoemancipation

Autoemancipation! was a short work; in the English version published by the American Federation of Zionists in 1916, it takes up only 23 pages. It begins with the famous words of Hillel in the Talmud, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And if not now, when?” (conveniently omitting the middle section, “If I am only for myself, what am I?”). From there, it carefully dissects the “Jewish Question” and the plight of Jews in both East and West, before offering a solution. Although it lacked anything like a detailed proposal for achieving its goals, it offered something more important: a complete reorientation in the Jewish fight for equality that resonated with those who read it. It concluded with a call to action: “Help yourselves, and God will help you!”

Pinsker rejected the assumption that anti-Semitism would gradually fade with Jewish integration into the non-Jewish world. The pogroms had convinced him that anti-Semitism was a permanent feature of Gentiles’ worldview, best understood in medical terms. “As a psychic aberration,” Pinsker wrote, Judeophobia (his preferred name for the condition) “is hereditary, and as a disease transmitted for 2,000 years it is incurable.” Therefore, Jews could not win acceptance by changing their behavior or demonstrating their fitness as citizens, or through the tools of rational persuasion.

What caused this pathological hatred? Jews, wherever they lived, were alien. In Pinsker’s view, it is only natural for nations to distrust foreigners who live among them, but Jews attracted special enmity as the “the strangers par excellence,” who were foreign not just in one place but everywhere they went. They had no home where they could live without the burden of foreignness.

Worse, nearly 2,000 years of exile had stripped the Jews of their nationhood, rendering them “the uncanny form of one of the dead walking among the living. The ghostlike apparition of a people without unity or organization, without land.” Having lost their “national self-respect,” it was only natural that they were despised by non-Jews. Pinsker observed that the Jews represented the opposite of what was considered good wherever they happened to live: “for the living the Jew is a dead man, for the natives an alien and vagrant, for property-holders a beggar, for the poor an exploiter and a millionaire, for patriots a man without a country, for all classes a hated rival.” In short, Jews would always be anathema, and could not hope for acceptance.

That assessment led Pinsker to an entirely new way of thinking about how Jews should improve their circumstances. Given the implausibility of Jewish acceptance in Gentile society, the continued Jewish quest for that acceptance was debasing. “In seeking to fuse with other peoples,” he wrote, Jews “deliberately renounced, to a certain extent, their own nationality. Nowhere, however, did they succeed in obtaining from their fellow-citizens recognition as native-born citizens of equal rank.” Even and perhaps especially in Western Europe, where Jews enjoyed full political equality, they never gained the acceptance of their fellow citizens and were constantly reminded that their political rights relied on the goodwill of non-Jews. That fragile contingency left them constantly anxious over the risk of losing these rights.

Herzl would later argue that a new political theory could answer these challenges, and Pinsker reasoned his way to a similar conclusion. For if the problem of Judeophobia, that hereditary psychic aberration, resulted from the Jews’ lack of nationhood and their dispersion, its solution would be to revive the Jewish nation. In Pinsker’s words: “It is our bound duty to devote all our remaining moral force to re-establishing ourselves as a living nation, so that we may finally assume a more fitting and dignified role.” Once the Jewish nation is returned to life, the Jews would take their place among all the other nations as equals. “The relations of the nations to one another may be adjusted fairly well by an explicit mutual understanding, an understanding based upon international law, treaties, and especially upon a certain equality in rank and mutually admitted rights, as well as upon mutual regard.” Even then, the Jews would still be distrusted, since a 2,000-year-old hatred would not simply disappear—an assessment that has so far proved more accurate than Herzl’s more optimistic prognosis—but they would at least enter the “tolerable modus vivendi” characteristic of relations among other nations.

The quest for emancipation—the common term for the removal of the discriminatory legislation that until the 19th century circumscribed Jewish life throughout Europe—relied ultimately on Gentile good will. By the Autoemancipation of the title, Pinsker meant that Jews would have to become masters of their own fate:

We are no more justified in leaving our national fortune entirely in the hands of the other peoples than we are in making them responsible for our national misfortune. . . . We must seek out honor and our salvation not in illusory self-deceptions, but in the restoration of a national bond of union.

To restore this national bond, recover their national honor, and accomplish what Pinsker termed “the greatest work of self-liberation,” he initially advocated that Jews find land available for purchase and fertile and productive enough to sustain a potential population of millions. It must be “uniform and continuous in extent” because dispersion is the cause of Jews’ lack of nationhood. There the Jews could create a state of their own, a safe haven to which their oppressed coreligionists could immigrate en masse. Pinsker was committed to finding a territory anywhere that would fit these conditions.

While writing Autoemancipation! Pinsker was aware of a small but steady migration from Russia and Romania to the Land of Israel, but he believed this “irresistible movement toward Palestine” was “mistaken.” This Ottoman backwater was inhospitable, with few natural resources and land that was difficult to cultivate, especially for East European Jews unfamiliar with the climate and inexperienced in agriculture. By 1884, however, in response to the question of where Jews might find asylum, Pinsker answered: “Wise men answer this question with a shrug of their shoulders, but the plain common people answer without hesitation—by migrating to Palestine.” He came to recognize the value of popular passion and embrace the unhesitating answer of the rank and file of the Jewish nation, who desired the creation of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, regardless of the practical difficulties the land posed.

III. The Lovers of Zion

On November 4, 1884 Pinsker gave the opening address to the first public assembly of the Ḥovevei Tsiyon, or “Lovers of Zion,” in the city of Kattowitz, in what is now Poland. The Kattowitz Conference preceded Herzl’s First Zionist Congress by thirteen years. The men attending the conference were representatives of independent local organizations, based mostly in Russia, that raised money and facilitated emigration and settlement in the Land of Israel. These grass-roots groups had limited financial backing and no diplomatic ties. Because tsarist Russia had little freedom of association, these organizations were technically illegal, which is why the conference took place in the then-German city of Kattowitz, just across the border. But the Lovers of Zion were not willing to wait for more favorable circumstance and, in the spirit of Pinsker’s pamphlet, had no desire to leave themselves dependent on Gentile largesse.

At the conference, the various local groups agreed to a loose form of organization, unofficially centered in Odessa. The attendees also committed to raising money and providing financial support for already-established colonies in the Land of Israel like Petaḥ Tikvah and Gedera. These settlements struggled to survive on subsistence agriculture and relied on philanthropy for survival. Conflict arose almost immediately between secular and religious activists regarding the religious character of the settlements, and of the eventual state that was to be established in the Land of Israel—a conflict not unlike those that divide the Jewish state today. As Pinsker commanded the respect of both religious and secular factions, he was able to forge a compromise by bringing religious leaders, alongside secular ones, into Ḥovevei Tsiyon’s leadership. Nonetheless, some members of both secular and religious factions walked away from the negotiating table unsatisfied and tensions over the question of religion persisted. These would come to the fore again in 1887 over the question of whether the settlements should be encouraged in observing the sabbatical year.

Much more pressing and divisive was the controversy over the purchasing of land. He argued, with characteristic caution, that Ḥovevei Tsiyon should focus on supporting existing settlements and helping them to become self-sufficient before organizing further migration and new settlements. Younger activists, like Menachem Mendel Ussishkin, fought against this approach, urging an acceleration of the pace of settlement. They feared that failure to seize the moment would allow inertia to set in and bring about the collapse of the whole project. Here too, the conference reached a compromise: new settlements would be encouraged, but at a slower pace than Ussishkin’s camp desired.

As these disputes show, Ḥovevei Tsiyon was by no means the effort of one man alone. Pinsker’s colleagues included Moses Leib Lilienblum, whose autobiography The Sins of Youth led many Jews to both Haskalah and Zionism, and Rabbi Samuel Mohilever, who led the movement’s religious faction. These, and others, are egregiously underrepresented in English-language scholarship, and fare little better in Israeli scholarship. But Pinsker’s life story perfectly encapsulates the Russian Jewish intelligentsia’s shift from integrationism to belief in autoemancipation, and he alone produced the movement’s manifesto. Despite his cautious approach to the pace of settlement, Pinsker was a key figure in supporting the Jewish returnees to Zion in the 1880s. Without his work and the support of Ḥovevei Tsiyon, the first settlements in the Land of the Israel were unlikely to have survived.

IV. Herzl’s Shadow

As early as 1902, mere years after Herzl published The Jewish State and organized the first Zionist Congress, a contributor to the Russia based Hebrew language newspaper ha-Ts’firah lamented that “the new Zionists don’t know Pinsker, the true founder of political Zionism.” Why were Pinsker and Ḥovevei Tsiyon so quickly overshadowed by Herzl?

At first glance, Pinsker and Herzl share many similarities. Both were raised in Jewish families that were relatively integrated into non-Jewish society, and both spent their formative years in diverse and generally tolerant cities, Odessa and Vienna respectively. Both grew disillusioned with integration and although they envisioned different strategies to achieve it, they both proposed the same solution to the problem of anti-Semitism: the creation of a Jewish state. In terms of personalities, however, Pinsker and Herzl were radically different.

Pinsker was cautious and taciturn. He did not turn suddenly to Jewish affairs as did Herzl, but was invested in them throughout his career, an interest he inherited from his father. Even in his Ḥovevei Tsiyon activism he urged restraint and favored slower settlement activity. He preferred to stay out of the limelight and led Ḥovevei Tsiyon reluctantly, only at the urging of others. When he wrote for the Russian-Jewish press, he usually did so anonymously. This was a man who was more comfortable in his study than speaking in front of crowd.

Herzl, meanwhile, relished being the center of attention. He had an established career in journalism—always under his own byline—before turning to Zionism. Attractive, young, and charismatic, Herzl stepped confidently into his role as leader of the Zionist movement and won people’s loyalty with ease. His commitment to grandeur, and even showmanship, helped make the Basel Congress such a moving event. Some Jews even named their children after Herzl, and wherever he went local Jews came out to greet him in huge numbers.

The differences between the two men came across on the page as well as in person. Autoemancipation! was a powerful work in its own way, but one hurriedly written and lacking the stylistic verve and eloquence of The Jewish State. In addition to its literary superiority, The Jewish State also benefited from better timing. When it was published, West European Jews were encountering more anti-Semitism than they had when Pinsker wrote Autoemancipation! The election of the vehemently anti-Semitic Karl Lueger as mayor of Vienna—a city with a large and prominent Jewish population—and the Dreyfus Affair, among much else, forced Western Jews to reckon with the same hatred with which the Russian Jews had continuously struggled. While Jews outside of Russia largely ignored Autoemancipation!, they were primed for the similar message of The Jewish State in 1896.

Finally, Herzl was more programmatic than Pinsker. He created a compelling historical narrative with a clear-cut beginning and end. Herzl’s characters were nation states, diplomats, and monarchs. The plan was simple: diplomacy would convince the Great Powers to create a state for the Jews. Pinsker’s pamphlet relied on the movement of the Jewish masses, and never explained exactly how they were supposed to be transported to their new homeland, or how that was supposed to lead to a Jewish state.

Political Zionism, based on diplomacy, played to Herzl’s strengths and his own forceful personality. By cultivating extensive networks of influential people, he gained access to the world of high politics, and sought to win over prominent politicians to the Zionist cause. In this respect, it diverged from the more democratic ideological foundations of Pinsker’s vision: what Herzl advocated was not self-emancipation, but reliance on Gentile goodwill. And it would be wrong simply to see Herzl’s movement as succeeding where its predecessor failed. His attempts to win the support of the Ottoman sultan and the German Kaiser left him emptyhanded. His diplomatic efforts brought the movement no closer to securing a Jewish state. Nonetheless, he cemented the idea that a Jewish state could only be attained with the help of the Great Powers as a central feature of Zionist thought.

When the First Zionist Congress met, Pinsker had been dead for six years, but many of the Russian delegates who attended were representatives of the organization Pinsker had founded, and brought his ideas with them. Herzl opposed Ḥovevei Tsiyon’s settlement plans because Jewish emigration to Ottoman Palestine was illegal under Ottoman law, and he feared they would undermine his position with the governments whose support he sought. Disagreement between Herzl’s followers and the settlement-oriented Russian Zionists posed an immediate threat to the unity and viability of the Zionist Organization, much as the conflict between Pinsker and Ussishkin. As at Kattowitz, a compromise would be found, but this tension between the desire to get Jews into the land by any means possible and the need to win international support for statehood continued right up until 1948.

Leon Pinsker and his pamphlet Autoemancipation! cannot be credited with initiating migration to the Land of Israel, which was already in progress, although it did much to encourage it further. Likewise, the intensification of settlement and the building of the infrastructure that contributed to the creation of the state of Israel only began after Pinsker’s death. But Autoemancipation! formulated a clear rationale and purpose for the return to Zion. It is no exaggeration to claim that Pinsker, through publishing his pamphlet and leading Ḥovevei Tsiyon, played a crucial and under-appreciated role in the Zionist movement. Without the followers won over by Pinsker’s arguments and the efforts of Ḥovevei Tsiyon, those early settlements, and the early Zionist movement, would likely have petered out. Had that happened, Ḥovevei Tsiyon’s organizational structure wouldn’t have been present to join Herzl’s Zionist Congress and—as we shall see—there would not have been the demographic facts on the ground in the Land of Israel on which later Zionists could build.

V. Ben-Gurion and the Spirit of Autoemancipation

The tensions between Herzlian political Zionists and Pinsker-inspired Lovers of Zion did not disappear after the deaths of these two men. Indeed, it can be seen in the contrast between the activities of Israel’s Herzlian first president, Chaim Weizmann, and its first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. It was the former who achieved the Balfour Declaration, but the latter who declared Israel’s independence in an act of self-reliance in the tradition of Pinsker.

To understand the difference between the two, it’s necessary to go back to the initial wave of immigration to the Land of Israel following the Russian pogroms, known in Zionist historiography as the First Aliyah. Although, as mentioned above, the First Aliyah suffered from attrition and limited economic success, it brought somewhere between 20,000 and 35,000 Jews to Palestine. Among these olim was Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the force behind the revival of Hebrew. The First Aliyah inspired and paved the way for the Second Aliyah which began in 1903 and brought an additional 35,000 pioneers. From then on, purchase of land and immigration increased steadily until the 1939 British White Paper, which effectively closed the door to further Jewish settlement. By that time, the Yishuv’s population had reached an estimated 450,000. It included basic foundations of self-government and a burgeoning civil society with schools, newspapers, and other institutions—most of which used Hebrew as their language.

All of this began before the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which was the quintessential achievement of Herzlian Zionism: a decision by a Great Power (Britain) to grant the Jews a homeland, achieved through Jewish diplomacy and cemented by international law. It was the high point of Weizmann’s career. A declaration of course was not the same as an actual Jewish state, and was dependent on continued British good will. But it made further Jewish immigration legal, and allowed the Yishuv to continue to grow. It also gave legal status to the Jewish Agency, led by Ben-Gurion, which became the Yishuv’s de-facto government. After World War II, when the Great Powers—now the United Nations, the USSR, and the United States—again took up the question of Palestine, they had to address the real presence of a large Jewish population in the territory, not merely the theoretical benefits of creating a Jewish state.

Chaim Weizmann, whose Zionist activism was inspired by the Herzlian approach, spent his career cultivating and maintaining productive relations with British politicians so that they might aid in the creation of a Jewish state. Weizmann was shaken by the White Paper because it essentially reneged on the commitment made in the Balfour Declaration. Even in his opposition to the White Paper, however, Weizmann never lost his faith in the British government and its legal processes. Reflecting on the blow dealt by these new policies, Weizmann wrote: “We took note of the fact that hardly a statesman of standing in the House of Commons had failed to declare the White Paper a breach of faith; and we felt that not we, in opposing the White Paper, were the law breakers, but the British Government in declaring it to be law.” British law, therefore, reigned supreme and even though the government erred in this decision, there was reason to maintain faith and continue the diplomatic work of winning British politicians over to the Zionist cause. Weizmann was not a lackey of London, but he maintained his faith that the Jewish state would be attained with the help of the British.

Even in these dire moments Weizmann focused on recruiting allies rather than despairing over the setback. He proudly noted, in his memoir Trial and Error, that Winston Churchill gave “one of the great speeches of his career,” condemning the White Paper in the House of Commons. But Churchill’s oratory was not enough to prevent the White Paper from passing, though Weizmann clarifies that the government victory was “extremely narrow.” As he left the House on the day the White Paper was issued, he “could not help overhearing the remarks of several Members, to the effect that the Jews had been given a very raw deal.”

David Ben-Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency and de-facto leader of the Yishuv, was far less sanguine than Weizmann about this “raw deal.” Before the White Paper was issued, Ben-Gurion ensured that the Jewish Agency acted only within the bounds of British Mandate law. The White Paper led him to change course. Its severe limitations on immigration and land purchase were a grave threat to the future of Zionism. In response, Ben-Gurion began to organize and facilitate illegal immigration. Additionally, he proposed purchasing more arms and expanding the Haganah, the Yishuv’s defense force, with the intention of carrying out armed resistance to British rule. With war looming, and an overwhelming sense that the survival of the Yishuv was dependent on the British, the Zionist Executive rebuffed Ben-Gurion’s proposal to strengthen the Haganah, eager not to antagonize the British.

Initially frustrated by the Zionist Executive’s decision, Ben-Gurion came to agree with it when World War II broke out. Hitler was a much graver danger to the Jews than the White Paper and therefore the Zionists would support the British war effort. Yet Ben-Gurion was not prepared simply to ignore the White Paper. He thus proclaimed that the Zionists “must assist the English in their war as if there were no White Paper, and resist the White Paper as if there were no war.” As a result, Ben-Gurion and the Haganah ceased violence against Mandate authorities, but continued to facilitate illegal immigration.

As the war turned in the Allies’ favor in late 1943, Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Agency ramped up assistance to the British war effort in order to accelerate the Allied march toward Berlin. By contrast, Menachem Begin’s Irgun militia, which had initially joined the Haganah in ceasing armed struggle against the British, renewed its fight against the Mandate. Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Agency urged the Irgun, along with the smaller and more extreme Leḥi (also known as the Stern Gang), to show restraint, but to little avail. The four months from November 1944 to February 1945 became known as the Saison, or the Hunting Season, in which the Ben-Gurion and the Haganah aided the British in capturing Irgun and Leḥi members.

True, Ben-Gurion sided with the Mandate authorities against his fellow Zionists. But this should not be interpreted as a sign of immovable, Weizmann-esque faith in the British. The Saison, like the war itself, was simply an instance in which interests temporarily aligned. For Ben-Gurion, it was an opportunity to assert the authority of the Jewish Agency over the secessionist organizations that rejected it. Weizmann, in contrast, cooperated with the British as a long-term investment that would lead to the creation of the Jewish state. Weizmann approached the British from a place of collaboration; Ben-Gurion approached the British from a place of opposition and autoemancipationism. The cooperation with the British that characterized the war years would rapidly deteriorate in the second half of 1945.

VI. A Return

As the war drew to a close, the Zionists eagerly expected the British to annul the White Paper and remove the restrictions on immigration and land purchase. They had an ally in Winston Churchill, and the Labor party, then in the opposition, had in 1943 reaffirmed its commitment to the creation of a Jewish national home. But in July 1945, Churchill was voted out of office. A few months later the new Labor government repudiated the party’s wartime promises and announced that the White Paper would remain in effect.

Ernest Bevin, the new foreign secretary, threw his support behind the White Paper. While not particularly anti-Jewish, Bevin believed that Jews were not a nation, only a religion, and therefore did not need a state of their own. Weizmann related that in the press conference immediately following this announcement, Bevin said “If the Jews, with all their suffering, want to get too much at the head of the queue, you have all the danger of another anti-Semitic reaction through it all.” Weizmann found this statement “gratuitously brutal” and was fully aware of Bevin’s lack of sympathy for the Jews and the Zionist project. Despite his frustrations, Weizmann continued cooperating with the British and trying to build friendly relations with members of the new government. He never lost faith that working with the Great Powers as the best means of realizing the Zionist movement’s aim.

On the ground in Palestine, the news that the White Paper was upheld was a call to more vigorous action, to which the Haganah responded with increased efforts to bring in more immigrants. Displaced Persons camps all over Europe were filling up with Holocaust survivors who, having faced the worst possible outcome of relying on non-Jewish political authorities for their security, were eager to settle in the Land of Israel. Ben-Gurion recognized this population as a vital resource and tasked the Haganah with sneaking them into the country.

The British authorities continued to interdict the Jewish refugees streaming into the Palestine, detaining them in Palestine or Cyprus. One of the most dramatic stories of this era is that of a ship acquired by the Haganah and named Exodus 1947—which inspired the titular vessel of Leon Uris’s novel. In July 1947, as the ship approached Palestine with 4,200 refugees on board, the British surrounded it and ordered it return to Europe. The Jewish refugees were eventually forced to disembark in Hamburg. The British argued that they were simply upholding the law, but as the horrors of the Holocaust were coming to light, sending Jewish survivors back to Germany provoked public outrage among Jews and non-Jews alike. It also led the Haganah to cooperate with the Leḥi and Irgun in resisting the British, blowing up bridges and interfering with the Mandate authorities’ ability to function.

The clash between Ben-Gurion’s camp and Weizmann’s supporters came to a head at the Twenty-Second Zionist Congress in Basel, December 1946. The first congress after World War II presented in microcosm the impact of the Holocaust on world Jewry. Weizmann recalled standing at the podium, looking down at the delegates, and “finding among them hardly one of the friendly faces which had adorned past Congresses. Polish Jewry was missing; Central and Southeast European Jewry was missing; German Jewry was missing.” The Zionist movement was now dominated by delegates from America and Palestine.

In addition to heart-wrenching demographic change, Weizmann observed a difference in spirit. There was a pointed “absence—among very many delegates—of faith, or even hope, in the British government, and a tendency to rely on methods never known or encouraged among Zionists before the war.” Weizmann opposed active armed resistance to the British rule by calling on the legacy of Herzlian Zionism. Standing at the podium, Weizmann pointed to Herzl’s portrait on the wall above him, crying “This is not the way! . . . If you think bringing the redemption nearer by un-Jewish methods, if you lose faith in hard work and better days, then you commit idolatry and endanger what we have built. Would I had a tongue of flame, the strength of prophets, to warn you against the paths of Babylon and Egypt. Zion shall be redeemed in Judgment—and not by any other means.” Weizmann, becoming a prophet of political Zionism, preached against anti-British violence as a sort of idol worship, completely foreign to the ways of Zionism. As the prophets’ pleas often went unheeded, so too were Weizmann’s. The people turned in a different direction.

Weizmann came to the Twenty-Second Congress as president of the Zionist Organization, but was not re-elected. In his memoirs, Weizmann reflects that he “left the Congress depressed.” As a result of his dogged faith in the British and opposition to armed resistance, he recognized that he became “the scapegoat for the sins of the British government.” The delegations from Palestine, led by Ben-Gurion, and from America, under the direction of Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver, agreed that the movement had entered a new phase. Reflecting on this moment, Weizmann mourned that “not only were the giants of the movement gone—Shmarya Levin and Ussishkin and Bialik, among others—but the in-between generation had been simply wiped out; the great fountains of European Jewry had been dried up.”

Weizmann viewed this new phase as Zionism’s nadir. He believed that the turn to active resistance was something new and foreign to the Zionist project. In a sense, however, it was actually a return to the attitude of earlier Zionists, the Ḥovevei Tsiyon, and the pioneers of the First and Second Aliyot. It was a return to Pinsker and Autoemancipation!

VII. The Foundations

As the termination of the British Mandate drew nearer, recognition of the Jewish state by the newly formed United Nations grew increasingly important to Ben-Gurion and the Zionists. The Zionists did not put much faith in the United Nations, but looked at it with great suspicion, fearing that they would fare no better in the hands of the UN than they did with the British. Yet they knew they needed it to give the Jewish state legitimacy.

The turn to the UN was, in a sense, a reversion to Herzlian political Zionism, but a number of crucial differences must be kept in mind. While political Zionism approached non-Jewish authorities as supplicants, seeking permission to create a Jewish state, Ben-Gurion approached to the UN with the understanding that however it might vote, Jews would act on their own to secure their independence. On the night of November 29, 1947, the streets of the Yishuv filled with Jews celebrating the UN’s acceptance of the partition proposal which guaranteed the formation of a state. Ben-Gurion, however, did not participate in the celebrations. He was painfully aware that the UN’s vote meant little to the Arabs on the ground who would take to violence in order to destroy the incipient nation. Ben-Gurion, as it turned out, was right and war broke out shortly thereafter. In the end, the Jews would have to fight for the statehood granted by the UN on the battlefield.

The state of Israel gained international recognition and survived its early years due to the complex interplay of legal and illegal activities, of diplomacy and autoemancipation, that drew on the legacies of both Herzl and Pinsker. True, international recognition of Israel was crucial, and it is exceedingly unlikely that the state would have survived, or even come into existence, without it. Nor is it possible that the Yishuv would have developed as it did without the Balfour Declaration 30 years earlier. Nonetheless, even Zionist diplomacy at the UN was rooted in Ben-Gurion’s autoemancipationst resistance to British rule. The acts that Weizmann imagined to be totally foreign to Zionism made the situation in Mandatory Palestine so untenable for the British that they turned the “Palestine question” over to the UN where the General Assembly voted in favor of partition. The Arabs violently rejected Partition and started a war with the intent to destroy the newly created state of Israel. It took the Haganah and its weapons to defeat them.

Israel won its independence and survived its early years due to the infrastructure, both physical as well as political, laid over the course of the first two Aliyot. The small settlements that Ḥovevei Tsiyon founded and supported in the 1880s led to the creation of larger towns and cities. The first neighborhoods of what would become Tel Aviv—Neve Tzedek and Neve Shalom—were built on the outskirts of Jaffa during the First Aliyah, long before Herzl arrived on the scene. Tel Aviv proper, which took its name from Herzl’s book, was founded during the Second Aliyah by Russian Jewish migrants to Israel. Meanwhile kibbutzim, the self-defense organizations that later became the Haganah, labor unions, and the Hebrew University all originated in this crucial early period of settlement. On the cultural front, Israeli literature, song, and folk dance also emerged in full force during these years. Though these migrants, young pioneers carrying the spirit of autoemancipation, numbered only in the tens of thousands, they created much of Israeli society as we know it today.

Israel succeeded because it built a country—with a civil society, government, and defense forces—before attaining statehood. As countless examples illustrate, efforts to secure a state through purely diplomatic means, through the UN or recognition by the Great Powers, without the foundations of a civil society, often result in low-functioning states. Herzl’s contributions, and his legacy as carried out by Weizmann, contributed crucially to the development of the Zionist movement and Israel and ought to be celebrated. But Pinsker’s legacy, the autoemancipationist spirit, is recognizable in the efforts of Zionists across the ideological spectrum, from left-wing Labor Zionists like Ben-Gurion to Revisionists like Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Menachem Begin. And as Israel reckons with its changing relationships with the Great Powers, and with the benefits and drawbacks of its dependence on the U.S., Pinsker’s message continues to resonate. Autoemancipation! had a far greater impact than Pinsker, sitting at his desk in 1882 writing this brief pamphlet, could have imagined. The Zionist movement and the Jewish state were built on the foundations laid there.

More about: Israel & Zionism