Over the last decade, there has been a growing debate in Europe, initiated primarily by animal-rights groups and environmentalists, about the desirability of banning religious ritual slaughter in the name of animal welfare. This debate has caused concern among Jews not only in Europe but also in Israel and North America, as the ban means for them—and many Muslims—the end of the production of the only meat they can eat.

It is difficult for Jews not to see, lurking behind the argument against animal suffering, the sly face of an anti-Semitism that has always been able to drape itself in the ideals of the moment. This fear is legitimate, but we must also keep in mind that it should not obscure the legal, political, and economic dimensions of the problem. For, when looked at from the right angle, the seemingly narrow controversy over ritual slaughter widens into a prism for better perceiving how a continent and culture are being torn between contradictory values.

I. The Carnivorous Challenge

To understand the sensitivity of Jewish communities toward the issue of ritual slaughter, it is helpful to discuss some basic notions about their relationship with animals in general and meat in particular. That relationship is strikingly close. According to Genesis, man was originally made by God to be a vegetarian, as in the Garden of Eden, where “every green plant shall be food.” (Later, however, the consumption of meat became an integral part of Jewish worship.)

Secondly, the Torah strictly prohibits the mistreatment of animals. It is forbidden for any human being to cut off a limb of a living animal and to eat it. Jews are also obliged to feed their animals before themselves, to relieve their suffering, and in general to cause them the least pain. They must make them rest on Shabbat and it is prohibited to muzzle animals to prevent them from feeding themselves during their work. One may not harness together an ox and a donkey.

Further, it is by saving the animals in his ark that Noah discovers the meaning of the human condition: responsibility. Indeed, the permission to eat animals was granted to mankind only after the flood and only on condition that blood, considered as a carrier of life force, would not be consumed. This ban on blood is central to Judaism.

Later, additional regulations appeared. After leaving Egypt, the Hebrews learned that they were only allowed to eat the meat of certain mammals, such as cows and sheep that have split hooves and chew their cud, and that they could partake of those specific animals that were permitted for sacrifice in the Tabernacle. Then, once they entered the land of Israel, Hebrews were allowed to eat “in every desire of [their] soul,” meaning even animals slaughtered outside the Tabernacle and outside the Temple for the pleasure of consumption. At this point, the Temple service became primarily sacrificial.

Now, the sacrifice (korban) was in no way an offering to God in exchange for benefits. It was in most cases a sin offering (korban ḥatat), which consisted of, after having unintentionally transgressed the law, making peace with oneself and getting closer to God by an act of giving. The meat of the animals slaughtered in that service was shared with those who had no land and therefore no basic food resources: the priests (kohanim), in charge of the ritual sprinkling of the blood.

Did these sacrifices have a pedagogical purpose, allowing the Hebrews to realize that the object of the sacrifice could only be destined for others and not for a deity who had no use for it, and that the material needs of their fellow Hebrews should be their own spiritual needs? And that, by the way, such a way of life formed an absolute difference from the surrounding peoples, who made offerings to their idols? This is what Maimonides assumed in the Guide of the Perplexed. Did the sacrifices have a cathartic function, of preventing violence by diverting “aggressive tendencies onto real or ideal victims, animate or inanimate but always not likely to be avenged,” as the rabbi Joseph Albo implied in the Book of Principles and the French philosopher René Girard thought? Whatever the answer, slaughter, in the Jewish view (although, of course, this is debated), remains an abnormal act, a concession to an imperfect world and that will end in the messianic era, when humanity will return to its original vegetarianism. Reflecting this, the rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook only ate meat on Shabbat, an exceptional event for an exceptional day.

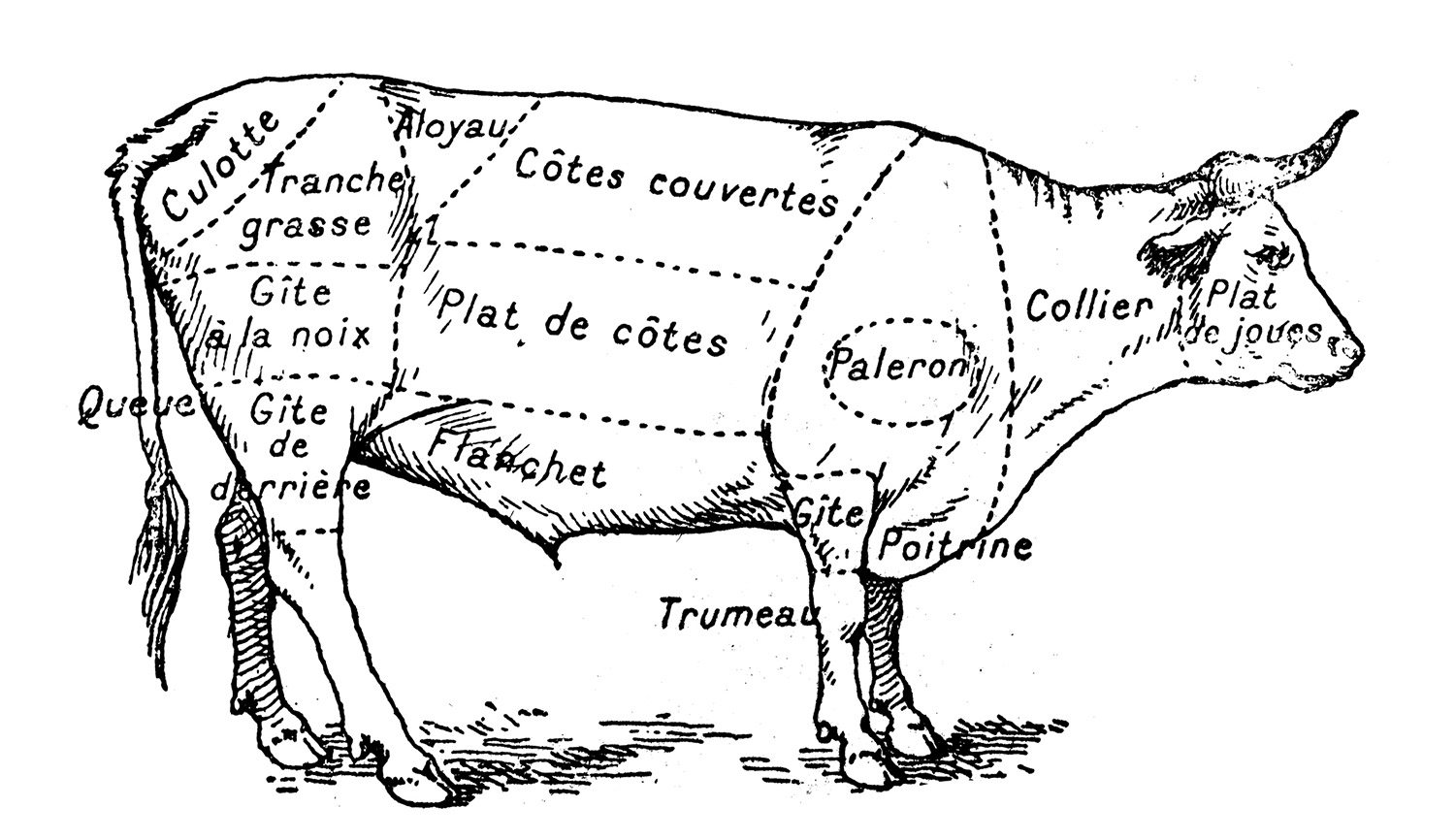

In the meantime, the Jews have developed an extremely meticulous method of slaughter that meets the dual requirement of ensuring that the meat of an animal contains no blood and of limiting the suffering of the animal as much as possible. This happens by the cutting of the trachea, carotid arteries, and jugular veins all at once and without pressure. In this way, about 70 percent of the total blood of the animal is spilled. Yet if the animal is stunned beforehand, as is now common in non-kosher slaughter, only about 30 percent is spilled. Hence the importance of the animal’s state of consciousness at the time of bleeding. There is also a prohibition against consuming animals’ sciatic nerve in memory of the biblical forefather Jacob’s wrestling match as described in the book of Genesis. All this is so important that it occupies an entire Talmudic tractate, Ḥulin.

It follows that the slaughterer (shochet), far from being the executor of the community’s dirty work, must be a scholar. This is impossible to explain to anyone who sees slaughter as solely the transformation of an animal into an object of human consumption. By taking a life to feed others, the shochet is responsible, to those who will eat the animal’s flesh, for ensuring that their consumption conforms to the norms on which the Jewish community is based. It takes him eight years of training to be able to change the status of the animal by an act that does not reify it but sanctifies it—that is to say, separates it from the material realm and shepherds it into the spiritual realm. Without the rite and the appropriate blessing, slaughter would be murder, just as without the prior Jewish blessing, the consumption of any product of nature is theft.

To give everything a meaning, to introduce one into the world where it does not exist, is characteristic of the Jewish approach to any act—including killing, one of the most degrading of all. In traditional Ashkenazi communities, the shochet, because he engaged in the most inhuman action tolerated by a human community, had to compensate for it with the most humane action possible: the duty of hospitality was incumbent upon him first and foremost.

After the animal has been killed as quickly as possible by the shochet (an act known in Hebrew as shechita) and the bleeding is complete, certain organs are checked by a specialist (bodek) to ensure that the animal is kosher. If the animal was not alive at the time of slaughter, or if the organs show signs of serious illness, it is considered carrion, forbidden for consumption. Today, animals declared unfit for Jewish consumption (which number more than 50 percent), are returned to the normal meat-processing circuit as soon as the veterinarian has given his approval. (The same is done for the hind parts containing the sciatic nerve.) It is quite possible that this obsession with ritually evacuating the blood was at the origin of the Christian accusations of Jewish ritual murder, recurrent since the Middle Ages. Indeed, in the Christian world, the killing of the animal, at best provided with a material soul, is a quite banal phenomenon; it raises no other question than that of limiting violence to what is strictly necessary in order not to give man a taste for it.

Muslims, on the other hand, borrowed their approach from the Jews by humanizing the killing of the animal as much as possible and by invoking God to grant themselves permission to kill it. However, one will not find in Islam as strict a code of rules as one finds in Judaism for the training of the slaughterer and the modalities of killing. Islamic ritual slaughter (dhakat), by cutting the throat (dabh) or by thrusting a blade into the supra-sternal fossa (nahr), is simpler than shechita. It does not involve any control of the animal before and after death, no specification of the quality of the killing instrument, and no professionalization of the slaughterer’s function. Any Muslim man can slaughter an animal as long as he respects basic criteria of faith, conscience, and morality. The means to reduce animal suffering are left to individual discretion. Prior to the great revival of rigorism in Islam in the 1980s, many Muslim decision makers in developed countries even allowed the consumption of animals slaughtered by methods acceptable to other members of the “People of the Book” tradition.

For the broader European public and especially for European judges, Jewish and Islamic ritual slaughter methods fall into the same category. In reality, they are very different. This misunderstanding and its consequences will recur later in this essay.

The awakening of a certain social sensitivity about the particularly brutal practices in slaughterhouses is recent; until the 19th century in Europe, only Jews paid any attention to animal welfare. It should be borne in mind that the stoning or public torture of animals was an ordinary street spectacle in Europe until the 18th century. At the end of the 20th and especially in the 21st century, this sensitivity was considerably heightened, in particular because of the recurrent series of scandals such as the spread of mad-cow disease. Consumers have become increasingly attentive to production methods. This has led to an even stricter control of the production conditions of all foodstuffs and the development of new techniques to limit the suffering of animals intended for slaughter. And this in turn means Europeans no longer consider Jewish ritual slaughter an unnecessarily fussy production but indeed a form of animal cruelty, even though very few people in Europe were at all interested in the issue until the 1960s.

Everything changed with the massive increase in the Muslim population over the last several decades. Today, Muslims represent about 7 percent of the European population—about 50 million people. The revival of Islam over that time, the radicalization of communities, has helped to put ritual slaughter back on the European public agenda. This phenomenon has also profoundly transformed the meat market, especially since Europe exports a considerable quantity of meat to Islamic countries, meat which must therefore be ritually slaughtered before shipping. At the turn of the century, the global halal market was estimated at 150 billion dollars annually, a huge number that gives some sense of why European producers might have some interest in meat export.

The sacrificial rite of Eid-el-Kebir played a special role in the transformation of public opinion. To commemorate Ibrahim’s (Abraham’s) sacrifice of the ram in place of his son, every Muslim father must kill an animal himself, though many prefer to delegate this rite. Then, one third of the meat is given in charity to the needy. Since Europe’s slaughterhouses lack sufficient space to satisfy such widespread demand, since the male participants lack skill or experience in slaughter, and since the whole situation lacks the usual legal and sanitary and animal-welfare precautions, the Eid-el-Kebir festival offers Europeans the spectacle of a yearly massacre carried out in abominable conditions. Animal-welfare organizations have raised an outcry, and European states have gradually been forced to take appropriate measures by creating temporary slaughterhouses that meet minimum technical requirements to avoid scenes of sacrifice in fields or backyards. Still, these sites have in turn attracted the further ire of the animal-rights activists, who have tried to ban them. In 2015, however, a Belgian judge refused, arguing on the basis of religious freedom and on the grounds that Muslims strive to avoid animal suffering and respect public-health requirements.

II. The Limits of the Legal Framework

The main concern that is raised about ritual slaughter has to do with the state of the animal in the moment of death: primarily, whether it is conscious or not. Thus, in the second half of the 20th century, legislators across Europe progressively adopted the principle of stunning before killing, which is forbidden by Jewish law. The aim is to limit the animal’s unavoidable suffering as much as possible, though reasons of hygiene, food safety, and the safety of slaughterers also play into the change. Jewish ritual slaughter, which, needless to say, is in the extreme minority of all animal slaughter on the continent, has been allowed to continue by virtue of a status of legal exception endorsed over decades by the European Convention on the Protection of Animals for Slaughter.

Yet a status of exception is not a status of right, and there is increasingly frequent questioning of the Jewish exception in the press and in the changing attitude of judges, in response to which the Jewish community has become increasingly nervous. In 2019, the Court of Justice of the European Union, whose function is to interpret EU law and ensure its uniform application in all member states, concluded that EU law does not allow products from animals that have been slaughtered without being stunned beforehand to be marked “organic.” The concept and appellation “organic,” the court concluded, implies that the welfare of the animal has been considered in every moment of its life, including its last, and not simply in the way it is raised and fed. In this way, it spontaneously extended the notion of “organic” far beyond what people tend to believe it means.

Another ruling, made by the European Court of Justice on December 17, 2020, has caused even greater concern in Jewish communities. The ruling announced that the protections for animal welfare outlined by one of the primary treaties of the European Union must, in certain circumstances, give way to the even more fundamental objective of guaranteeing religious freedoms and convictions. Yet in the end the Court ruled that a decision by the Flemish government to mandate ritual slaughter only after stunning would ensure “a fair balance between animal welfare and freedom of religious worship.” This is a strange formula, as there is no balance in it at all, since for Jews and many Muslims, eating meat from animals that are stunned before slaughter is simply forbidden. The Simon Wiesenthal Center therefore decided this judgment was one of the ten worst anti-Semitic events worldwide in the year 2020. Ironically, the EU had announced that in 2021 it was going to devote more effort to combating anti-Semitism. To prove its good intentions, it started the year by upholding a ban on a central Jewish ritual.

Is the EU in charge here? Or do the individual member states retain their sovereignty on this matter? It’s a blend of both. The states remain sovereign—as long as their actions don’t break EU law. It is therefore up to the states to decide whether they wish to allow Jews and Muslims to benefit from an exception. Since the decision-making process of states is democratic, a majority vote in domestic parliaments is sufficient to end the religious exception and prohibit ritual slaughter.

Which means, inevitably, that the state of exemption rather than state of right will not be strong enough to protect ritual slaughter. Already, many individual states are moving to prohibition. Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Slovenia, six Austrian provinces, and the Belgian regions of Flanders and Wallonia do not allow any exemptions from the stunning requirement. The idea is also gaining ground in Germany, the UK, and the Netherlands. In Poland, the High Court reversed its own 2012 ban on ritual slaughter in 2014 following an appeal by the Union of Jewish Communities on the grounds of religious freedom. The economic stakes are high, since Poland is one of the main exporters of kosher and halal meat not only to the rest of Europe but also to Israel and Turkey. The production chain is fighting to keep this market of more than 5 billion dollars, but the parliament keeps coming back to put an end to it. There is one exception, at least: in Finland, a constitutional law committee this year voted, in the name of religious freedom, against a bill banning kosher and halal slaughter.

The evolution of the European attitude is dictated, on the one hand, by the conviction that ritual slaughter is cruel, and on the other hand by the idea that the law is meant to translate the expectations of a society in a given time and place into normative form. For Jews, this second stance is an absurdity: law should be reflection of a universal and absolute principle that does not have to be adapted to the tastes of the day. As for the first idea, the debate is complex. Some of the issues in it relate to the socio-technical context of the slaughterhouse—the way in which the work is mechanized, the pace of work, the know-how and tools of the slaughterers, the restraining devices, and so on, all of which affect animal welfare. Here we will focus on a couple of the main issues. The first concerns the reality of suffering during slaughter, and the second concerns the choice of which principle should prevail: animal welfare or freedom of religion.

In the 19th century, observers still considered Jewish slaughter to be more humane than ordinary slaughter. Today, secular scientists and experts argue the opposite. They estimate that mammals can remain conscious for two to six minutes of suffering after cutting, whereas Jewish and Muslim experts believe that these animals lose consciousness after ten to fifteen seconds. (Dhakat, which is less meticulous than shechita, makes the agony a little longer.) The Court of Justice of the European Union thus found in 2019 that methods of slaughter carried out without prior stunning are not equivalent to methods of slaughter after stunning, in terms of ensuring a high level of animal welfare at the time of killing.

To understand the debate, it is important to know that there are three stunning techniques used in slaughterhouses. The first is mechanical, caused by perforating the cranium by a metal rod—an act which sometimes happens imperfectly, causing great suffering. (It has a 2-to-54-percent failure rate in sheep and a 6-to-16-percent failure rate in cattle, according to studies by the French National Institute for Agronomic Research). The second method of stunning, intended mainly for sheep and poultry, consists of the application of an electric current to the head, a process known as electronarcosis. The third method, mainly used for pigs, involves inhalation of carbon dioxide which causes suffocation over several minutes.

As these descriptions indicate, stunning is almost a euphemism here. When animals are bashed in the head or ruthlessly choked, their suffering is doubled—they are victims of two cruel acts instead of one. The renowned animal-science professor Temple Grandin has even found that calves are more stressed when the hand of the stunner is waved in front of their face than when they are slaughtered properly in a kosher manner.

In the end, stunning is in most cases killing by another name. One does not survive a perforation of the brain or several minutes of gassing. Electronarcosis—the process of putting the animal into a stupor by running electricity through its brain—allows for a method of stunning that is in theory reversible. But in reality, it is not always reversible: plenty of animals die of electrocution in the process.

All this means that in addition to being doubly cruel, stunning, since it kills, is not a valid method of ritual slaughter. It is certainly unacceptable to Jews. To Muslims it’s a little more unclear. Some Muslims accept electronarcosis because Muslim law is vague on the specifics of the subject.

There’s a variant of the stunning debate that some think offers a space for compromise. In Austria, Estonia, Greece, and Lithuania, immediate stunning after bleeding rather than before is used—indeed, mandated—to anesthetize the animal during its last seconds of suffering. During the debate that preceded the vote on slaughter in the Brussels parliament, the representative of the Islamic community declared that post-incision stunning (as well as electronarcosis) was an acceptable compromise for Belgian Muslims. Some Conservative Jewish communities have likewise accepted this as a compromise. (Reform Jews as a general matter do not much care, since the movement has repudiated the binding nature of Jewish law in general, and the rules of kashrut within it.). But the representatives of Orthodox Judaism do not seem to be willing to go down this road because they are not certain that the animal will bleed as thoroughly. They also do not feel that they have the legitimacy to question a tradition that is several thousand years old, given the normative role of tradition in Jewish law.

In any case, by explaining to Jews and Muslims that they should stop ritual slaughter because stunning is reversible, by imposing technical conditions such as the size of the blade, the quality of the cutting edge, or the way the animal is moved after bleeding, European legislators—who are responding to and echoing public opinion—think they are being both logical and fair. Since the animal is not dead after electronarcosis, they argue, the slaughter becomes compatible with Jewish law.

This is where an essential problem arises, which the broader European public rejects but which is nonetheless obvious: the MPs are interfering in Jewish law. They are not simply saying that religious tradition or religious liberty must take a back seat to the protection of animals, but taking it upon themselves to decide what compromises Judaism should allow. In this way, they are stepping inside the religion and in effect defining Jewish identity itself, in contradiction not only with Jewish law but also with the principle of separation of religion and state. Shimon Cohen, the campaign director for Shechita UK, a London-based organization that lobbies against shechita bans, expressed a widely shared amazement in Jewish communities that a secular court of law could or should assume the right to tell people if and how they can practice elements of their faith.

Moreover, any questioning of shechita or limitation of the procedures of ritual slaughter is a way of reducing Jewish autonomy and impinging on the capacity of Jewish communities to self-structure. This obvious fact did not escape the attention of the Belgian Council of State, for whom “it is not in principle the task of the public authorities to pronounce on the legitimacy of religious beliefs or on the ways in which they are expressed, and that they therefore have no role in assessing the theological correctness of the convictions of the faithful or of certain currents of a religion.” Of course, in the region of Wallonia, Belgian MPs ignored this. They even disregarded the efforts of the president of the Israelite Consistory (the official representative of the Jewish community to the Belgian government), who had gone so far as to propose that slaughterers no longer be appointed by the Consistory but by a regional public body certifying their competence. (The idea was to retain kosher slaughter but give Belgian MPs the feeling that they were masters of the process.)

Therefore, if ritual slaughter is going to be saved, the Jews of Europe must work urgently on convincing the public, the MPs who represent it, and the judges who interpret the law that the ordinary consumption of food in accordance with religious criteria should be considered a religious practice and must be defined by the members of the religion and not anyone else.

In a 2019 resolution, the European Parliament sidestepped the issue. It called on member states “to introduce religiously compliant animal-slaughter programs in slaughterhouses, taking into account that a significant proportion of live animal exports are destined for Middle Eastern markets”—and also called on the Commission “to ensure that animals are stunned, without exception, before religious ritual slaughter in all Member States.”

The contradiction did not bother the members of the European Parliament. But it is obvious to many other, more aware actors. For many decades, European lawyers and judges had been at odds with the legislators who expressed in their parliaments the expectations of public opinion. The former defended freedom of religion and argued for the maintenance of the religious exemption because they thought that their mission, as defined by the founding texts of European human and civil rights, was to protect minorities from the tyranny of the majority.

Today, this dam is breaking. European courts are gradually moving away from a defense of freedom of religion towards defining for themselves a framework for the methods of ritual slaughter. Likewise, they are moving from an absolute loyalty to neutrality in the assessment of the compulsory nature of ritual slaughter without stunning towards an assessment of the validity and legitimacy of religious beliefs as well as their methods of expression.

Last but not least, the orientation of key European legal texts on the subject has changed. Contrary to its title, the real objective of the 1993 directive “on the protection of animals at the time of slaughter or killing” was first and foremost to implement undistorted free competition in the European single market by establishing common standards “in order to ensure rational development of production and to facilitate the completion of the internal market in animals and products,” and then to guarantee the safety of food products. The basic idea, in other words, was that slaughter techniques should not act as technical barriers to trade across the continent, and that animal protection was a secondary objective. Although animal welfare is still not an explicit objective of such texts and treaties, public pressure is forcing it to be read into them, highlighting their fragility.

III. The Ideology behind the Law

European opponents of ritual slaughter sometimes denounce this economic reality as something that makes all consumers “accomplices” of Jewish and Muslim communities and practices. They are partly right. Remember that a large proportion of the animals slaughtered by shechita is eventually declared unfit for Jewish consumption. The same applies to the backs of kosher carcasses from which the sciatic nerve is no longer removed. Muslims, for their part, often favor the front parts and offal, leaving the back parts behind. Thus, a considerable amount of ritually slaughtered meat inevitably ends up in the sourcing channels of ordinary meat without any particular labeling. Consumers therefore cannot know whether their meat comes from animals slaughtered without prior stunning. Since the 1980s, this practice has made it possible for many small slaughterhouses to become economically viable.

Unfortunately, this structuring of the market, the absence of an Islamic consensus on the definition of halal, and the ease of obtaining a permit for ritual slaughter, have all led to an over-exploitation of the exemption from stunning. These abuses are dictated by economic motives unrelated to the religious demands of the communities concerned. The main thing for many slaughterhouses is to have only one channel of production and to obtain maximum output from it, regardless of the ultimate destination of the meat. This is not illegal, but it plays with legality, since those who act in this way, many of them unscrupulous slaughterers in the halal sector, know that they are misusing the legal exception for ritual slaughter. In the sheep and poultry production chains in particular, maximum speed means maximum profit and maximum suffering. Sometimes they do not even wait for the death of the animal to start cutting it up.

On the one hand, because of the sloppiness of this part of the supply chain, many Muslim consumers are pushed towards meat slaughtered under clearer and higher standards, for fear of consuming meat improperly slaughtered in these unscrupulous slaughterhouses. On the other hand, some non-Jewish and non-Muslim consumers are outraged at the possibility of unknowingly consuming meat that has not been prepared to the standards they prefer and expect. This expectation was created by European authorities themselves. The European Commission writes that “member states must ensure that meat [from animals slaughtered without stunning] does not end up on the general market, including through appropriate labelling and traceability mechanisms.” This wish is perfectly legitimate since it is what consumers demand. At least that is what the proponents of labeling would have us believe, although a 2015 study by the same European Commission, concluded that “for most consumers, information on the method of slaughter was not an important issue until it was brought to their attention.” Hence the energy expended by animal-welfare groups to bring this information to the public’s attention. This right to choose one’s product on the basis of credible labeling is reasonable enough. But it poses several problems.

The first is simply technical. It is very complicated to ensure the veracity of labels given the wide variety of actors sharing a myriad of tasks between slaughter and distribution, some of which are in the private domain, others in the public domain. Drawing a line between these areas is a political act in itself. Furthermore, kosher or halal labels are applied at the discretion of producers and the religious communities they serve. They are not subject to any particular government protection, like the protected designations of origin famous for denoting certain wines, spirits, cheeses, etc.

The second problem is political. To indicate on the packaging of a piece of meat that the animal from which it comes has not been stunned clearly means that it has been slaughtered for Jews or Muslims. The natural reaction of the public is therefore: we can no longer know what we are eating because of the Jews and Muslims. During the Brussels debate, which ended with the exception for ritual slaughter being maintained, the Belgian MPs had to decide not only between freedom of religion and animal welfare but also between animal welfare and the risk of stigmatizing minority communities.

The third problem is related to animal welfare itself. Opponents of ritual slaughter know, of course, that Jewish and Muslim consumers will be forced to import kosher and halal meat if the exception is ended. In that case, there will always be a ritually slaughtered animal somewhere in the world to satisfy the needs of these communities. (Hence those worried meat exporters in Poland and Belgium, who don’t want to lose important markets.) In essence, the issue here is to push the act of slaughter beyond Europe’s borders, not to make it impossible. What these opponents want is the relief of their local conscience more than the welfare of the animals themselves.

This turns out to be a common feature of the animal-welfare debate. At the same time as ritual slaughter has become more objectionable, animals in Europe are still the subject of bloody games, particularly bullfights, which are part of “cultural traditions and regional heritage” according to European regulations and to which the regulation on animal welfare does not apply when they are killed “during cultural or sporting events.” Noting this discrepancy, Islamic associations have tried, unsuccessfully, to have Eid-el-Kebir considered a cultural event. The European Commission has cautiously shied away from the subject on the grounds that “the European Union is not competent to deal with all aspects of animal welfare. This is the case, for example, with regard to [. . .] the use of animals in artistic or sporting events (bullfights, rodeos, circuses, dog or horse races, etc.).”

Even more hypocritically, hunting is still permitted in Europe—the organization of an event, usually collective, during which individuals take pleasure in tearing the flesh of living animals with lead shot and inflicting suffering on them leading to their death. The same might be said for fishing and angling. When petitioners asked how Belgium could allow hunting but prohibit ritual slaughter, the European Court of Human Rights replied that hunting was a cultural tradition and therefore entitled to protection. The Court of Justice of the European Union elaborated on the same theme, arguing that animals killed during cultural or sporting events or in the context of hunting or fishing activities are not subject to compulsory stunning, since the former are not intended to produce foodstuffs and that the latter would lose all meaning if the animals were stunned.

Rarely has the absurdity of value preferences in the West been better understood.

Further examples proliferate. The Norwegians, who prohibit ritual slaughter, practice whaling, which inflicts all imaginable suffering on these highly intelligent cetaceans. As for the Danes, they slaughtered more than ten million COVID-infected minks under abominable conditions on government orders. And what about the appalling massacre of pilot dolphins in the Faroe Islands, a self-governing nation under the external sovereignty of Denmark? Following the age-old tradition of grindadrap, encouraged by the local government, boats drive the dolphins into a bay and they fall into the hands of fishermen on land, who enter the water up to their waists and kill them with knives in a blood-red sea. A petition with almost 1.3 million signatures demanding a ban on these slaughters only resulted in a promise from the authorities to limit the killing to 500 animals per year. Not to mention the lobsters that are boiled alive in water everywhere.

Hunting is permitted in Islam (not all the time and not everywhere) and even the killing of an animal by a trained dog is allowed. But all forms of hunting are forbidden in Judaism: a man cannot profit from a being that has suffered.

Paradoxes and contradictions go far beyond the sordid euphemism of “stunning.” In fact, the invocation of freedom of religion may be a poor line of defense on the part of the communities affected by the ban on ritual slaughter. It is possible to imagine a religion that worships by making animals suffer (there have been such religions, as there have been human sacrifices). Some religions authorize or prescribe acts that are forbidden on European soil: forced or underage marriages, polygamy, ritual mutilations, legal amputations, etc. For Jews, whose law is based on responsibility towards others and, secondarily, towards animals, the incomprehension comes from the reversal of the situation. European Jews are divided between amazement, anger, and concern. To them, a civilization that has been morally backward for thousands of years suddenly explains that they have become archaic in their practices and that animals have rights.

Though it may sound surprising to some, this dimension of the debate is essential. In Judaism, humans have rights because they are essentially different from animals in their ability to be responsible for their actions. Human rights are the natural outcome of thinking rooted in the universalism of Jewish law. On the other hand, being alive or sentient (i.e. able to perceive through the senses) does not grant any rights. For the last decades, libraries have been written about animal rights. This is nonsense under Jewish logic: animals have no rights. Humans, on the other hand, have responsibilities towards animals, deep ones explained clearly and seriously in many Jewish texts. The enlightened West now disagrees, and assigns animals the fundamental rights that to Jews come with belonging to the human species. Can we imagine a being with rights being directed to a slaughterhouse? This is what the debate is about.

In the end, it is hard to disentangle these campaigns from anti-Semitic sentiment. This has been the truth for a long time, long before animal welfare was such a popular cause. More than 60 percent of the Swiss electorate voted against ritual slaughter in 1893 after a clearly anti-Semitic press campaign. (Though it is interesting to note here how business interests have again tried to counteract popular sentiment. In 2001, in the name of religious freedom as well as money, the Swiss Federal Department of Economic Affairs, supported by the Federal Commission against Racism, tried to repeal the ban. In the end, the Swiss Animal Protection Service succeeded in preventing that measure. Then that service overstepped, by proposing a ban on the import of meat from non-stunned animals. The executive branch refused, arguing that an import ban would be contrary to the principle of non-discrimination enshrined in several articles of a major international trade treaty.)

In any case, the Swiss anti-Semitism campaign was followed over 100 years later in France. Just last year, in the election for the French presidency, the Green party and National Rally (extreme right) candidates committed themselves “in the name of animal dignity” to ban ritual slaughter. The latter went further by again proposing to ban the import of kosher or halal meat as well. Such initiatives are obviously intended to make life difficult, if not impossible, for Jews and Muslims. (They are also contrary to a very explicit EU regulation of 2009: “a Member State may not prohibit or impede the putting into circulation on its territory of products of animal origin from animals which have been killed in another Member State on the grounds that the animals concerned have not been killed in a manner which complies with its national rules which aim to ensure greater protection of animals at the time of killing.” Again, free trade is at the heart of the Union.)

In truth, shechita has always been central to anti-Semitic discourse and practice in Europe. On April 21, 1933, the Nazi regime passed a law banning ritual slaughter and imposing electric stunning to ensure animal welfare. It contained no reference to Jews, yet, of course, it was all about them. This Nazi law was more respectful of animals than the texts promoted by animal advocates in the 21st century, as it also prohibited cooking fish and crustaceans without first stunning them. When asked by German Jews what to do, the rabbi Y.Y. Weinberg from Berlin confirmed the prohibition against eating non-ritually slaughtered meat, but pointed out that he did not see the Nazi legislation as specifically anti-Jewish. But it cut against Jewish values on a deeper level. He believed, he said, that the ban on slaughter would continue after the fall of the Third Reich because the moral motivations behind the law, however flawed, were part of a fundamental trend. He understood, in other words, that the apparent respect for the animal at the expense of the humanization of its slaughter by man—which ritual slaughter represents—was part of a cult of nature that was making its way into the European mind. What’s more, he understood that Nazi paganism was the violent form of such a more subtle and deeper paganism.

We can even assume that there is a partly unconscious Pauline underpinning in the desire to prohibit ritual slaughter, since Christians have always reproached the Jews and then the Muslims for sacrificing animals for meat, thus inventing justifications to killing instead of simply killing them to eat them. For Christianity, the only truly meaningful sacrifice is that of Christ, the Lamb of God. From this perspective, surrounding the killing of animals for food with legalisms constitutes a sort of Pharisaic hypocrisy: if you intend to take a creature’s life for your own nourishment, don’t try to sacralize the act with elaborate ritual. The same is true for the circumcision of the flesh instead of the heart. It is therefore no coincidence that the banning of ritual circumcision is already taking shape in many European countries in the name of the child’s freedom of choice as a “next step” against Jewish—and Muslim—life.

We are thus gradually discovering that it is not so much the suffering of the animal that is at the heart of the debate on the ban on ritual slaughter but rather a certain idea of suffering—or a certain ideology that chooses certain sufferings over others. In a world where euthanasia is becoming more and more legitimate, even commonplace, the idea that human life should be protected is receding day by day. Not that Judaism ascribes to the absolute idea of life being sacred in the Christian sense; there are certain situations where it is preferable to renounce it than to renounce one’s humanity. But it remains a value to be defended, where secular Europe gradually sees an archaism. As the former French MP and minister Amélie de Montchalin put it, “There is an age when one becomes a very important financial burden for society, when the question of the early end of life must be asked; we must put an end to the taboos.” Europeans thus increasingly favor making sure humans die quickly, while protecting animals from suffering. If one day human slaughterhouses are once again organized in Europe, which is seeming likelier by the year, they will resemble the aseptic and peaceful euthanasia centers of Soylent Green more than the Nazi camps.

As these examples show, more than a case of intentional anti-Semitism, in the sense that the Jews are being targeted by measures intended to make their life difficult, the ban on ritual slaughter is essentially the result of a growing disjunction between Jewish ideals and those of the West. Between the second half of the 18th century and the Second World War, the integration of Jews into European society and the claim of universalizable principles by the civilization that welcomed them had given the impression to many Jews of a kind of “end of history,” of reconciliation justifying all forms of assimilation. Even though the Shoah was an unimaginable reminder, many Jews still want to believe that their values and those of the secular West are the same, and that those values had flourished after the defeat of Hitler, ensconced in the ideals of human rights. But the abolition of the ethical centrality of the human, the pagan sacralization of nature, the idea that animals have dignity and rights, the fight against suffering that justifies euthanasia, not to mention other social abuses, show that the rapprochement between the moral values of the two was perhaps only an accident of history. More and more Europeans will define their identity by belonging to a democratic society of informed consumers rather than by reference to universal principles.

Among the supporters of the ban on ritual slaughter, the distinction between anti-Semitic intentions, those that serve the interests of anti-Semites, and those that are influenced by anti-Semitic ideas without their authors even realizing it, is therefore subtle. This proves the extraordinary solubility of anti-Semitism in all ideologies.

In the ritual ban case, the Jews are in a way collateral victims of the effects of Islamic immigration and the European reaction to it, of the consequences of business strategies in the breeding sector, of the ignorance of judges, and of the evolution of ideologies alien to their values. Industrial and judicial actors have encroached on the field of religious norms, blurring the boundaries separating religion, politics, and economics.

Instead of accepting the idea that there are only imperfect and negotiated solutions in this matter, and that a reasonable accommodation involving the emendation of the legal norm at the margin is probably the best solution, community representatives and animal-welfare advocates are launching into an ideological battle the radicalization of which can only benefit the slaughter industry and Muslim extremists. Indeed, the regulation of ritual-slaughter practices, especially in the context of Eid-el-Kebir, or even their prohibition in many European countries, allows Muslim fundamentalists to prove that European civilization is betraying its promises of freedom of worship, that it is therefore Islamophobic, and that their aim to destroy it is legitimate.

The issue of ritual slaughter is above all an opportunity for Jews to discover the extent to which Western civilization is going off course and to ask themselves what role they should play in it—or more precisely whether they still have a role to play before the advent of the messianic era which will impose universal reconciliation and vegetarianism. In the meantime, it must be acknowledged that not all animal lovers are anti-Semites. But many of them hate Jews, and, as it happens, the more rights animals have, the fewer rights Jews have.

More about: Jewish World, Kashrut, Ritual, Ritual slaughter