On the current American Jewish scene, one group stands out for its seemingly successful integration of traditional religious behavior and belief with full participation in modern society.

Consider the landscape. On the liberal side of the religious spectrum, Conservative Judaism, until recently the largest of the denominations, identifies itself as traditional, but only a minority of its adherents strive to observe the dictates of Jewish law (halakhah). As for more liberal movements, most of their members make no claim to be exemplars of traditional Judaism but rather regard themselves as advocates of—to invoke the names of the best-known movements—reform, reconstruction, or renewal. Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the continuum, one finds Orthodox groups that, while punctiliously observant, self-consciously insulate themselves to one degree or another from Western culture or explicitly reject the assumptions of modernity.

This leaves the sector known as Modern Orthodoxy. Relatively small in number, making up just 3 percent of American Jewry as a whole—and by no means comprising all who identify themselves as Orthodox—it alone seems to have found the sweet spot: a synthesis of the modern with traditional Jewish observance. Recent surveys, including Pew’s Portrait of Jewish Americans, make clear just how well the Modern Orthodox have combined both parts of their name.

1. Who Are the Modern Orthodox?

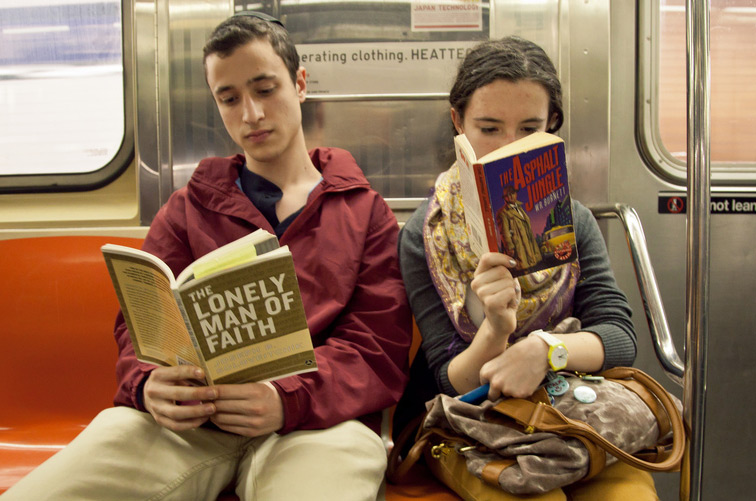

Organizing their family lives far more traditionally than do their liberal counterparts, the Modern Orthodox tend to marry earlier and to maintain a fertility rate well above replacement level; only small percentages intermarry. In order to insure the transmission of their religious commitments, they enroll nearly all of their children in the most immersive forms of Jewish education. Their synagogues, unlike most of those in the Conservative or Reform orbit, are teeming with regular worshipers every day of the week. Many sizable ones offer multiple prayer services every morning, afternoon, and evening, accommodating the busy schedules of individual worshippers. They also report rising numbers of men and women participating in study classes, and even of teenagers seeking out opportunities to learn on Sabbath afternoons. In a reinforcing loop, as one rabbi notes, “more intensive learning has created greater levels of observance.”

Synagogue life is further reinforced by the life of school and summer camp. Day-school attendance from early childhood through high school has become de rigueur for Modern Orthodox families. According to Pew data, 90 percent of those between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine have attended a day school for at least four years—a much higher figure, incidentally, than the one for their parents or grandparents. The figures for summer camps are comparably impressive.

None of this would be feasible without financial resources. Nationally, according to Pew, 37 percent of Modern Orthodox households have incomes of over $150,000, a figure not matched by any other Jewish denomination. In the metropolitan New York area, home to the largest concentration of Orthodox Jews of all stripes, the Modern Orthodox contingent shows the largest proportion earning $100,000 or more and $150,000 or more.

This relative affluence makes it possible for some in the community to support key institutions with generous donations, including scholarship assistance for day-school families. It also means that a large majority are able to shoulder the costs of Jewish living. Only those with resources—and commitment—can afford to live within walking distance of synagogues, purchase kosher food products, pay membership dues and building-fund assessments to synagogues, and, most expensive of all, cover K-12 tuition costs in day schools and send their children to Orthodox summer camps. Despite this heavy financial burden, there is no evidence that significant numbers have opted for public schools—or decided to limit the size of their families.

Finally, none of this comes at the expense of active participation in American society. Just like their counterparts elsewhere in the Jewish community, the Modern Orthodox attend college and earn advanced degrees at far higher rates than most other Americans. Both men and women go on to work, as we have seen, in the more lucrative sectors of the American economy. Some rise to positions of great distinction in their fields of endeavor, including in American public life (e.g., Jack Lew, the current Secretary of the Treasury; Michael Mukasey, former U.S. Attorney General; and Joseph Lieberman, former Democratic nominee for the Vice Presidency).

In short, Modern Orthodoxy in America appears healthy and vibrant, with functioning communities not only in large metropolitan areas but in nearly every mid-size Jewish community and even some smaller cities like Indianapolis, New Orleans, Bangor, ME, and Worcester, MA. Given the movement’s successes—and the cachet of dynamism that attaches to it—one might expect its leaders to be in a mood to congratulate themselves.

And yet that is not the case. A close reading of what Modern Orthodox leaders are saying publicly, and even more bluntly in private, reveals a great deal of anxiety about current trends within their communities. (In what follows, I will be relying in part on interviews conducted on the understanding that quotations would not be attributed.)

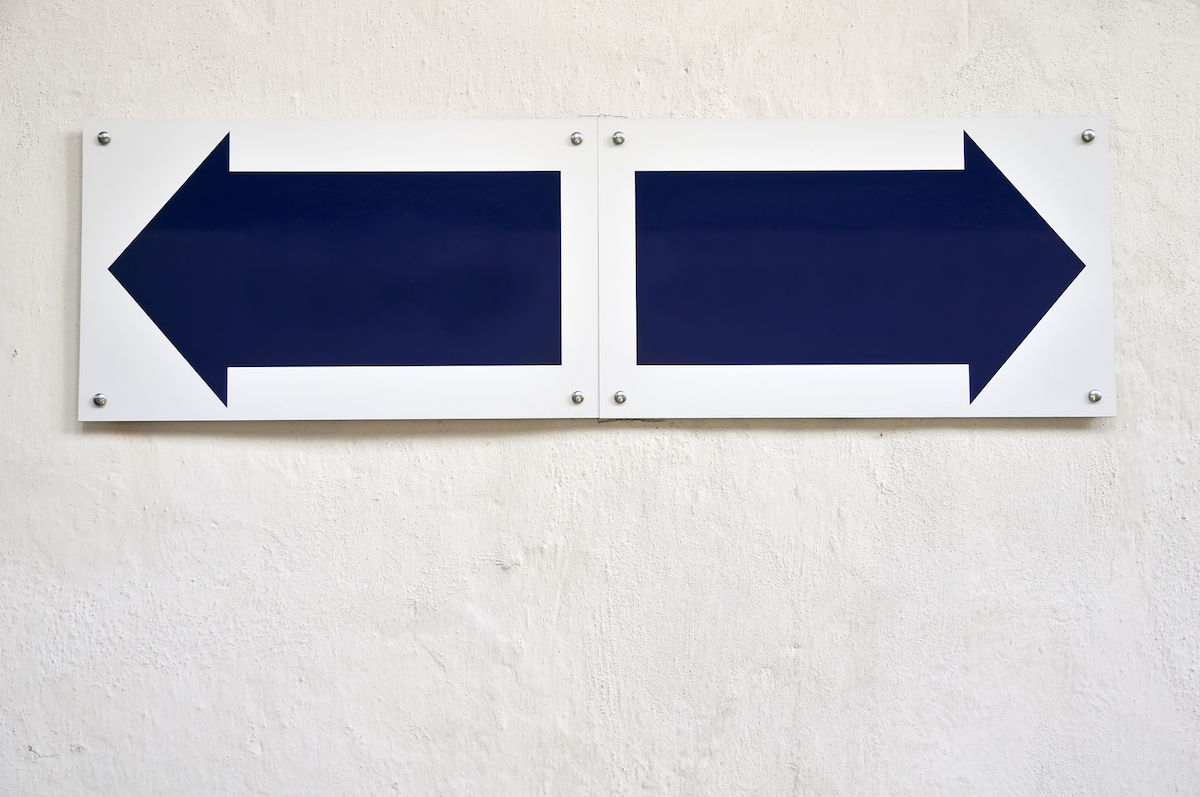

The anxieties being voiced have partly to do with numbers. Although the majority of those raised Modern Orthodox remain in that camp, the community does suffer defections, leading to worries about the possibility of demographic decline. But it is not only the potential erosion of its population that agitates the movement. A battle now rages for its soul—a tug of war over both practices and ideas that is pitting rabbis against each other even as some lay people work to push their synagogues onto new paths. At bottom, this internal struggle is over nothing less than the foundational assumption of the movement: that it is indeed possible to combine fidelity to traditional Judaism with modern values and understandings.

2. Pressure from the Right

To grasp the dynamics of the current struggle, it is critical to understand that it is playing out against challenges from both the “traditional” and the “modern” side of the equation. (Specialists on Orthodoxy have sub-divided it into many more groupings than two, but these are the major ones.) I’ll begin with the traditionalist challenge, which derives from the increase and growing self-confidence of another sector within the larger Orthodox world itself. That sector comprises the haredim, often known in English as the “ultra-Orthodox.”

The haredi camp encompasses both a number of hasidic sects and the spiritual descendants of their no less pious historical antagonists: the mitnagdim, or opponents of Hasidism, since that movement’s emergence in the 18th century. In the metropolitan New York area, haredim tend to cluster in enclaves like Williamsburg, Boro Park, and Crown Heights in Brooklyn and certain neighborhoods of Queens, as well as Lakewood, New Jersey and a couple of upstate New York counties. Haredi communities also exist in such cities as Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Wherever they are, the haredim have distinguished themselves not only by their aloofness from much of Western culture and learning, or by the wary distance they maintain in social interactions with Gentiles, but also by their self-segregation from their fellow Jews, emphatically including the Modern Orthodox—and precisely because of the latter’s accommodation of American mores, openness to the wisdom of the Gentiles, and willingness to interact with non-Orthodox Jews and their leaders.

Historical antecedents to the current stand-off between the modern and haredi sectors of Orthodoxy are not far to seek. During the mass migration of East European Jews at the turn of the 20th century, some rabbis strove to recreate the all-embracing religious culture of Eastern Europe in the New World setting. Jeffrey Gurock, the foremost historian of American Orthodoxy, labels these rabbis “resisters”—the main object of their resistance being the intrusion of American ways into their lives. Against them stood more moderate immigrant and native-born rabbis whom Gurock labels “accommodators.” Each group established its own rabbinic organization (or, in the case of the resisters, three separate organizations).

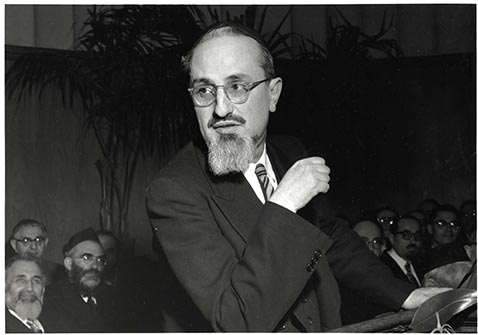

As the immigrant population adapted to America, the accommodating or Modern Orthodox position triumphed. Symptomatically, Modern Orthodox rabbis played an outsized role as chaplains during World War II; in the postwar era, the dominant face of American Orthodoxy was that of Yeshiva University-trained rabbis (and their counterparts at the Hebrew Theological College in Skokie, IL) who were joined together in the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA). The Modern Orthodox ideal was conveyed by the motto of YU, Torah u’madda, usually translated as Torah and secular knowledge or, more broadly, Western culture and learning. For second- and third-generation American Jews attracted to this synthetic ideal, the figure they looked to was Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, who embodied the ideal through his mastery of rabbinic texts and his broad knowledge of and continuing engagement with Western philosophy.

But even as Modern Orthodoxy reached the peak of its influence, an influx of Holocaust-era refugees from both Nazism and Communism gave a powerful boost to the resisters’ cause. The newcomers came with an ideology of separatism that had developed in Europe and found institutional expression in the Agudath Israel movement established in the early part of the century. As the haredi Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg of Baltimore’s Ner Israel yeshiva put it: “there is an ‘otherness’ to us, a gulf of strangeness that cannot be bridged, separating us from our compatriots.”

During the second half of the 20th century, the key lines of division hardened. The resisters were intent on rejecting much of “enlightened” Western culture—whose bankruptcy, in their view, had been exposed in the depravity of the Holocaust—and no less bent on insulating themselves from what they saw as the corrupting morals of secular modernity. The accommodators, for their part, while recognizing that not everything condoned by modern fashion was in sync with traditional Judaism, were open to absorbing “the best that has been thought and said,” regardless of its source. They flocked to universities and entered the professions, working side by side with non-Jews. They also maintained connections with Jews who were not traditionally observant but with whom they were prepared to work toward common ends. The most noteworthy common end was Zionism, which they embraced despite its largely secular leadership—a step shunned by the resisters, many of whom remain staunchly non-Zionist to the present day.

In the face of withering criticism hurled at them by their critics among the resisters, Modern Orthodox Jews insisted on the legitimacy of their way of life—stressing, in addition to the embrace of Zionism, the value of what Jews can learn from Gentiles; full participation in the larger society (bounded only by strict adherence to Jewish ritual observance); and the provision to girls and women of the same kind of Jewish education received by boys and men (though not necessarily in mixed-sex settings). As we have seen, this insistence paid off handsomely.

Now, however, several developments have combined to give rise to a well-founded anxiety. One source of concern, alluded to above, is demography. Just a few decades ago, the modern sector constituted the large majority of Orthodox Jews; in our time, it has become vastly outnumbered by the Orthodox resisters and is on track to decline even further. As compared with the 3 percent of American Jews who (according to Pew) identify themselves as Modern Orthodox, 6 percent identify themselves as haredi. In absolute numbers this translates into an estimated 310,000 adult haredim compared with 168,000 adult Modern Orthodox.

The disparity only widens when we look at younger age cohorts. Whereas those raised Modern Orthodox constitute 18 percent of American Jews over sixty-five, they represent only 2.9 percent of those between eighteen and twenty-nine. Something closer to the reverse holds among those raised haredi, who constitute only 1.6 percent of Jews aged sixty-five and older but rise to 8 percent of the eighteen-to-twenty-nine-year-olds.

And then there are the children. A 2011 population study of Jews in the New York City area estimated the number of haredi children at 166,000, roughly four times the number of Modern Orthodox children. Marvin Schick, who used different categories in a 2009 national census of day schools, counted 125,000 children in haredi schools versus 47,000 in Modern Orthodox and so-called Centrist Orthodox schools. (The latter subgroup eschews coeducation in its middle schools and high schools.) Since then, by all accounts, the numbers of haredi children have only increased.

To be sure, this is not the only circumstance depleting the numbers of Modern Orthodox Jews in the United States. Another one, ironically, stems from the movement’s great success in imbuing its young with Zionist values. Precise numbers are lacking, but by some estimates as many as 20 percent of Modern Orthodox youngsters who spend a year or more in Israel during the “gap” between high school and college end up making their homes there for at least some period of time. Needless to say, settling in Israel is socially and religiously approved behavior within the Modern Orthodox world; but that does not diminish its demographic impact on the community as a whole.

Still another worrying sign is the not insignificant rate of defection to more liberal movements. Thus, among those between the ages of thirty and forty-nine who have been raised Modern Orthodox, fully 44 percent have moved religiously leftward; among those between eighteen and twenty-nine, 29 percent no longer identify as Orthodox. (The commentator Alan Brill may have been the first to coin the term “post-Orthodox” for this population.) True, as noted above, Modern Orthodoxy is much more successful than liberal denominations at retaining its members, and it continues to attract from them as many as it loses; but the losses hurt.

If the relatively static size of their community, and the sheer demographic heft of the haredim, afford grounds for worry about the long-term viability of the Modern Orthodox way of life, beyond this concern lies another, related one: what some Modern Orthodox rabbis describe as a crisis of confidence among their laity. A salient symptom of that crisis, visible even among some otherwise highly acculturated Modern Orthodox families, is the decision to gravitate rightward toward haredi or semi-haredi schools and synagogues. Such families are driven, contends one of their rabbis, by “religious insecurity and feelings of guilt about that insecurity.” This rabbi therefore sees his role as twofold: insisting on the validity of modern Orthodoxy even as he encourages his congregants to intensify their commitment and practice. As he admits, it is a difficult balance to negotiate, and for some it does not suffice. Another rabbi, voicing exasperation over the rightward drift in his community, musters sarcasm to describe his congregants’ perceptions: “If you are not [religiously] serious, you go to my shul; if you are more serious, you go to more right-wing shuls because there are communal advantages to being there.”

As it happens, the Pew data suggest that the movement rightward may be balanced by a movement of haredi Jews traveling in the opposite direction. Moreover, those joining “right-wing shuls” do not generally move into haredi communities. It would thus be more accurate to see the so-called “slide to the right” as a matter less of massive defections to the haredi camp than of a shift within Modern Orthodoxy, led in this instance by those inclined to adopt aspects of haredi life while remaining nominally Modern Orthodox.

In some cases, the “slide” takes merely symbolic or token form, as when men wear black hats during prayer and women adopt haredi-style head coverings while otherwise continuing to maintain their very modern style of life. More significant, and much more distressing to stalwarts of Modern Orthodox values, has been the assimilation—some would say infiltration—of a “neo-haredi” worldview into some of the movement’s key institutions.

Since the passing of Rabbi Soloveitchik from the scene some 30 years ago, the Yeshiva University world has lacked an authoritative figure who personifies for the broader public the synthesis proclaimed in YU’s motto of Torah u’madda. Meanwhile, a neo-haredi group of roshei yeshiva—the term, often translated as deans of talmudic academies, more accurately connotes advanced teachers of rabbinic texts—has planted its flag at YU’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Rabbinical Seminary (RIETS), which educates, ordains, and shapes the religious and halakhic worldview of Modern Orthodox rabbis. In addition, Modern Orthodox day schools often employ haredi teachers who likewise communicate their ideology to impressionable students and may encourage them after graduation to attend an Israeli yeshiva or girls’ seminary where neo-haredi perspectives predominate. Of late, some long-time Modern Orthodox synagogues have also taken to hiring haredi or neo-haredi rabbis to fill their pulpits. And the community as a whole has become dependent on haredim who fill certain ritually critical roles, including as scribes who write Torah scrolls and other religious documents, kosher slaughterers, and supervisors of kosher food production.

Most subversive of all has been the internalization of the idea that haredi Judaism represents the touchstone and arbiter of Orthodox authenticity, period. This has placed Modern Orthodoxy on the defensive, handcuffing it to a way of thinking at odds with its founding assumptions. Willy-nilly, by absorbing the resistant mindset, important sectors of the movement have thereby undermined Modern Orthodoxy’s accommodative ideology and, worse, have made it more difficult to help their members navigate as observant Jews who embrace modern culture.

3. Pressure from the Left

If the challenge represented by the haredim exerts pressure on modern Orthodoxy from one direction, another and equally great challenge makes itself felt from the opposite direction. To Rabbi Yitz Greenberg, speaking at a recent forum on the Pew study, Modern Orthodox Jews live “on the same [cultural] continuum” as their non-Orthodox counterparts, being no less “exposed to the attractions of modernity and the acids of skepticism/historical criticism/social mores,” and no less likely to succumb to those twin forces, both the “attractions” and the “acids,” than are Conservative, Reform, or for that matter non-affiliated and secular Jews. Rabbi Greenberg even attributes the “demographic decline” of the movement primarily to this factor.

Actually, as we have seen, the problem is not (or not yet) one of serious decline but rather of demographic stasis. But there can be no doubt that Modern Orthodox Jews have become at least as alert to the most controversial issues roiling their movement from the Left as from the Right. To adapt Jeffrey Gurock’s nomenclature of resisters versus accommodators, which he applied to the struggle within the larger Orthodox world between the haredim and the Modern Orthodox, we may say that Modern Orthodoxy itself is now beset by a no less bitter or momentous struggle: between its own internal resisters attracted by haredi Judaism and accommodators more willing to adapt Jewish law to 21st-century ethical sensibilities.

Undoubtedly, the most hotly debated set of issues concerns the status of Orthodox women. Sexual equality is now taken for granted in most Modern Orthodox homes, and holding males and females to different standards is increasingly unthinkable. Under the circumstances, why should it not occur to some girls that they too might don t’filin (phylacteries), traditionally the accoutrements of male worship? How much Torah and Talmud ought girls and women be encouraged to study? May women serve as synagogue presidents? May they conduct their own prayer services, lead parts of mixed services, or wear t’filin during public worship? And, drawing the greatest heat: what are rabbis prepared to do to release “chained” women (agunot), whose husbands have refused to grant them a proper writ of divorce?

Other debates center on the proper treatment of homosexuality and homosexuals in the Orthodox community; how the community should relate to non-Orthodox Jews; the authority exercised by the Israeli chief rabbinate in matters pertaining to American Orthodox Jews; the authority of congregational rabbis vis-à-vis that of roshei yeshiva; the latitude, if any, for interpreting the theological category of “Torah from Heaven”—i.e., the belief that the Torah was dictated verbatim by God to Moses; and more.

In short, the same culture wars that have engulfed non-Orthodox Jews, Catholics, and Protestants now rage in the modern-Orthodox world.

This is not the place to discuss the complex legal and theological arguments on these issues advanced by different rabbinic authorities. Suffice it to say there are deep differences over who is credentialed to issue legal rulings and how flexible is Jewish law. On one side, Modern Orthodox resisters argue they are constrained by halakhic precedent even when it comes to mitigating the suffering of agunot. On the other side, accommodators tend to interpret Jewish law as in some degree subject to historical circumstances; Blu Greenberg, the preeminent leader of Orthodox feminism, has encapsulated this view tersely, declaring that “where there’s a rabbinic will, there’s a halakhic way.” Many advocates of new thinking see the principal driver of change as the larger Orthodox community, with rabbis lagging behind.

While such disagreements on matters of Jewish law occupy the foreground, a series of cultural forces in the background are seen by all as shaping current debates.

Rabbinic authority is waning. Rabbis across the spectrum of Modern Orthodoxy, resisters and accommodators alike, point to a community that has absorbed American understandings of the sovereign self. “What rabbis say does not matter,” is a refrain I have heard repeatedly. “Authority is in retreat,” declares one rabbi; says another, “People like traditional davening (prayer) and singing; but when it comes to halakhah impinging on them, then they resist.” In one haredi school, the head of Jewish studies states without any prompting, “In today’s age, the model of rabbinic authority does not exist. We don’t live in ghettoes anymore, so you have to reach students where they are. Saying ‘because it is so’ no longer works.”

In private conversation, the same lament recurs regardless of ideological position, although some go on to lay the blame for the loss of rabbinic authority on their opponents. On the accommodative side, the prevailing sentiment is that hidebound rabbis have brought this situation on themselves because, when it comes to the demands of modernity, they are “oblivious and clueless.” From the resisters, one hears that the accommodative wing has undermined the authority of recognized legal decisors by running to peripheral figures who are only too willing to approve innovations. Many sense their loss of authority so keenly that they shy away from asserting their views on the major cultural issues of the day even when they personally feel strongly about them.

Accelerating these trends is the new reality of the Internet. Thanks to it, states one rabbi, “everybody has a right to have a position; everyone has a de’ah [opinion] about everything.” Educated Jews can look up answers to their own questions and choose from the answers available online. Many feel empowered in this role simply by dint of their day-school education and by the time they have spent studying in Israel, even as they are also encouraged by modern culture’s stress on individual autonomy to act according to the dictates of their conscience.

In this connection, day schools themselves are faulted by some for inadequately preparing their students to cope with the intellectual and moral challenges they encounter once they enter college. Rabbis on both sides agree that the failure lies in the deliberate neglect of questions of belief, theology, and the “why” of observance. From my own visits to Orthodox day schools, I question this critique. To me the problem seems more fundamental: there is no way fully to prepare Orthodox young people for the transition from their insular and homogeneous environment to the environment of the university, where the reigning values are so at odds with traditional Judaism. Be that as it may, however, efforts to remediate the situation are being made by rabbis in both the resistant and accommodative wings who are undertaking to teach their congregants about what is relevant and meaningful in Judaism rather than focusing solely on the study of texts. “I used to give heavy-duty classes on rishonim and aharonim,” one rabbi on the side of the resisters informed me, referring to classical rabbinic commentators. “Now I teach about derekh eretz [proper behavior], women and ritual observance, and tz’dakah [Jewish giving].”

One thing is certain: an estimated 70 percent of Modern Orthodox college students are enrolled in secular institutions of higher learning, and the impact of their experience there cannot be ignored. True, many of the parents and grandparents of current students also attended secular colleges, but it can be postulated that academic values and assumptions have changed since then, or that they are instilled far more explicitly than they were in the past, or both. On every campus today, incoming students are required to attend an intensive orientation program during which they are exposed to strongly formulated judgments about diversity, tolerance, and correct thinking. In this hothouse atmosphere, how is it possible for Orthodox students to argue in defense of the unequal treatment of women in the domain of religious observance? Can one conceivably emerge from a college experience today without having encountered attitudes toward sexual behavior at odds with traditional Orthodox beliefs?

Making it still harder to shelter today’s Modern Orthodox Jews is that they have strayed beyond the commuter colleges favored by an earlier generation. Once on campus, moreover, they are also less likely to shy away from courses on sexual roles, psychology, comparative religion—or modern biblical criticism—that will challenge views they absorbed during their day-school years and from their elders.

As with the challenge from the haredim, so with the challenge from “modernity,” one can trace the effects on the institutional level as well as the personal. Acknowledging the seriousness of both challenges, some among Modern Orthodoxy’s accommodative leaders and activists, male and female alike, have been pushing to reinvigorate and reinforce the movement’s founding ethos from within. To generalize, one might say that these efforts are aimed simultaneously at fending off the inroads of “haredization” and at incorporating, to some unspecified degree, the “open” ethos of modern liberal culture.

In 1996, an organization, Edah, was founded with that just that dual purpose in mind. Its leader, Rabbi Saul Berman, issued a pamphlet spelling out “a variety of Orthodox attitudes to selected ideological issues”—with the emphasis on “variety.” The issues ranged from the treatment of women in Jewish law to the meaning of Torah u’madda, from pluralism and tolerance within Orthodoxy to outreach aimed at non-Orthodox Jews. A year later, Edah was joined by the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance (JOFA), whose declared mission is to advance “social change around gender issues in the Orthodox Jewish community.”

Although Edah folded after a decade, JOFA continues with its work. And in the meantime, a number of other institutions and initiatives have arisen, each dedicated to fostering change in the Modern Orthodox world. They include Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT), an accommodative rabbinical seminary competing with YU’s RIETS, and Yeshivat Maharat, which styles itself as the “first institution to ordain Orthodox women as clergy”; both of these institutions are associated with a camp that has come to be called Open Orthodoxy. Allied with them is the International Rabbinical Fellowship, whose announced aim is to stand up for “the right, responsibility, and autonomy of individual rabbis to decide matters of halakhah for their communities.”

In the same orbit, if not necessarily of the same mind, are women-only prayer groups as well as “partnership minyanim” where men and women share the responsibility of leading different parts of the prayer services in a manner deemed acceptable to select rabbinic authorities. To disseminate new thinking, Modern Orthodox bloggers have been busy putting forth more “progressive” perspectives. One of them, the website TheTorah.com, grapples with the findings and conclusions of modern biblical scholarship, long regarded as inherently inimical to the teachings of traditional Judaism.

It is not unusual for some Modern Orthodox Jews and their rabbis to pick and choose among these activities. Members of women’s prayer groups, for example, may confine themselves to that initiative alone. Some students at YCT may support partnership minyanim while others do not. Some students at YCT and Yeshivat Maharat decline to identify themselves personally with Open Orthodoxy. Interestingly, it has been estimated that as many as 40 rabbinical students at RIETS itself would participate in a partnership minyan even though several of the leading talmudists at that institution have unequivocally proscribed such prayer services.

In sum, it is problematic to assume that individuals, even if they share a willingness to stretch the boundaries of Orthodoxy, form part of a common accommodative camp. Nor is it possible to quantify the number of Modern Orthodox Jews sympathetic to any of these efforts, though most observers assume it is relatively small and limited to a few centers of liberal thinking in New York, Washington, Boston, and Los Angeles. Still, just as it means something that Modern Orthodox congregations in, for example, St. Louis and Kansas City have sought out women to serve in a quasi-rabbinic role, it seems safe to assume that the 85 or so rabbis ordained so far at YCT and now occupying positions on campuses, in day schools, in chaplaincies, and in pulpits all around the country have had an impact of their own. The same can be said for the ideas making their way into every corner of the Modern Orthodox community through the reach of the Internet.

4. Toward a New Synthesis?

The most basic consequence of these cumulative changes is an increased awareness that the ground is shifting. As one observer has put it, “everyone knows the lines are moving.” The same individual notes how, “in shuls, people talk about how far to the Right modern Orthodoxy has gone.” Meanwhile, for those opposed to Open Orthodoxy, the ground is similarly perceived to be shifting, albeit in a distinctly different if not heretical direction.

The discomfort has led some rabbis to speak of a widening chasm within the movement and the inevitability—if not the desirability—of a schism. On the resisters’ side, those insisting that lines must be drawn have mostly limited themselves to fighting against new practices rather than ostracizing people, although, in a few synagogues, men who participate in partnership minyanim have been banned from leading services in their home congregations, and there are concerted efforts to bar YCT graduates from being hired by major Modern Orthodox synagogues. Some resisters have also taken to dismissing their opponents as closet Conservative Jews; to one prominent rabbi, the Open Orthodox should be known as “the observant non-Orthodox.”

For their part, advocates of Open Orthodoxy have shown little hesitancy about castigating their traditionalist opponents as reactionaries. Resentment toward Yeshiva University boils over in statements that the institution has fallen under the sway of rabbis with no understanding of today’s world and has become intellectually bankrupt. By contrast, Open Orthodox rabbis pride themselves on their hospitality to those who are not Orthodox. “We create an open space and do not say ‘no,’” one leader declares. Another draws the distinctions differently: “YU is modernist; [its people] think they are right. They draw lines in the sand. YCT people are post-modern. We see no conflict between intellectual openness and using critical tools, even as we remain committed to halakhah.”

And then there are those in the middle who feel sympathy for both sides and want a peaceful resolution that will keep everyone in the same camp. At a celebration of recent RIETS ordainees, a keynote speaker emphasized a single theme: we at YU are open; we have always stood for openness. Was this a peace offering to the progressive side of the spectrum, another salvo in the battle over legitimacy, or perhaps both? Others watch in embarrassment as “the hotheads” denounce each other. In most quarters, there is a sense that the current situation is unsustainable.

Of course, it is possible to view the factionalism within Modern Orthodoxy as a sign of vitality. Thus, one might say that differences have arisen because those on each side, equally committed to the Jewish future, are alarmed by the unhelpful ideas or policies being promoted by their counterparts on the other side. One might even remark that, in the fastidiously “non-judgmental” climate prevalent today in the rest of the American Jewish community, it is refreshing to encounter Jews prepared to stake a claim to what they see as true, necessary, and obligatory.

Worth noting, in any event, is that the programs and institutions spawned by rival factions are stimulating a welcome spirit of creativity. As Yehuda Sarna, the rabbi of New York University’s Bronfman Center, has observed, “There are multiple Torah and college options, multiple rabbinical schools, multiple forms of Orthodox Zionism, multiple ways of engaging with modernity, multiple entry and exit points to the community.” One merely has to cite the range of Orthodox websites issuing commentaries on the weekly Torah portion, and compare those offerings with the paucity of non-Orthodox counterparts, to appreciate the dynamism. The same can be said about bloggers in all sectors of the Modern Orthodox community who address everything from matters of theology to preparing brides for their wedding night.

Moreover, despite conflicts over practices, Modern Orthodox Jews of all stripes observe the same religious common core—daily prayer, kosher food restrictions, laws of family purity, Sabbath and festival celebrations. In fact, one of the contentions of the accommodators is that they are in no danger of going the way of Conservative Judaism precisely because, whereas the Open Orthodox live and work in religiously observant communities, Conservative rabbis historically made legal decisions for communities that did not observe Jewish law. Open Orthodoxy can experiment with new ideas and interpretations, they contend, because the commitment to Jewish law will keep them and their followers in check.

In “The Rise of Social Orthodoxy,” a recent essay in Commentary, Jay Lefkowitz put this perspective succinctly: “I imagine [that] for many others like me, the key to Jewish living is not our religious beliefs but our commitment to a set of practices and values that foster community and continuity.” Assumed in this formulation is that practices and values will remain unaffected by changing beliefs. But is that right? In fact, as we have seen, a whole set of core Modern Orthodox assumptions is under assault both from forces outside Modern Orthodoxy and from the partisans of those forces within, and there is considerable evidence that some practices, and even some values, are changing as a result.

Thus far, the Modern Orthodox world has managed to flourish and persist by creating a community of practice and by focusing most of its intellectual energy on intensified Talmud study. This is not to be minimized. The movement’s vibrant communal life, high levels of observance, and serious engagement with traditional texts are monumental achievements. But, caught as Modern Orthodoxy is between the absolutism and insularity of haredi Judaism and the realities of an open and radically untraditional American society, are those achievements sufficient to retain a population well integrated into American life and profoundly influenced by its mores, assumptions, and values?

The urgent question for Modern Orthodoxy is which values can be accommodated without undermining religious commitment and distorting traditional Judaism beyond recognition—and, conversely, what losses will be sustained if Modern Orthodoxy should undertake more actively to resist the modern world in which its adherents spend most of their waking hours. The same urgent question, mutatis mutandis, has confronted other Jewish religious movements in the past, and has continued to haunt their rabbis and adherents long after they made their choice of a path forward. That is one reason why today’s unfolding culture wars within Modern Orthodoxy carry far-reaching implications not only for that movement but for the future of American Judaism as a whole.

_____________________________

NOTE: My thanks to the following rabbis who agreed to off-the-record interviews for this essay: Saul Berman, Avi Bossewitch, Yonatan Cohen, Zev Farber, Jeffrey Fox, Barry Freundel, Kenneth Hain, Yosef Kanefsky, Bob Kaplan, Dov Linzer, Yechiel Poupko, Steven Pruzansky, J.J. Schacter, Uri Topolosky, Kalman Topp and Daniel Yolkut. I also interviewed Maharat Ruth Balinsky and Elana Stein Hain. And I benefited from conversations with Rabbi Yitz Greenberg, Professor Benjamin Gampel, Dr. Larry Grossman, Jay Lefkowitz, and Ruthie Simon. I’m very grateful to fellow participants in the Oxford Summer Institute in Modern and Contemporary Judaism, where an earlier draft of this essay was discussed. Special thanks to Steven M. Cohen, who ran copious data for me and helped me parse them.

Responses

- The Unresolved Dilemmas of Modern Orthodoxy by Jack Wertheimer

Everyone agrees that the movement needs to rethink and revamp. Very few agree on how. - Against Open Orthodoxy by Barry Freundel

Being both “open” and Orthodox sounds to me like an excuse for anything goes. - How to Rejuvenate Modern Orthodoxy by Asher Lopatin

Modern Orthodoxy as it developed in mid-century America was dynamic, vibrant, challenging. Thanks to Open Orthodoxy, it will be again. - Why Modern Orthodoxy Is in Crisis by Adam Ferziger

A realignment is occurring in the Orthodox world; to flourish, the Modern Orthodox need to recover their sense of collective purpose. - Let Us Now Praise Modern Orthodoxy by Sylvia Barack Fishman

Against all odds, Modern Orthodoxy has successfully mixed serious religious engagement with modern life. Now it just has to retain the courage of its own convictions. - Modern Orthodoxy, and Orthodoxy by Samuel Heilman

How does Modern Orthodoxy fit into the greater Orthodox world?

More about: American Jewry, Halakhah, Jack Wertheimer, Modern Orthodoxy, Open Orthodoxy