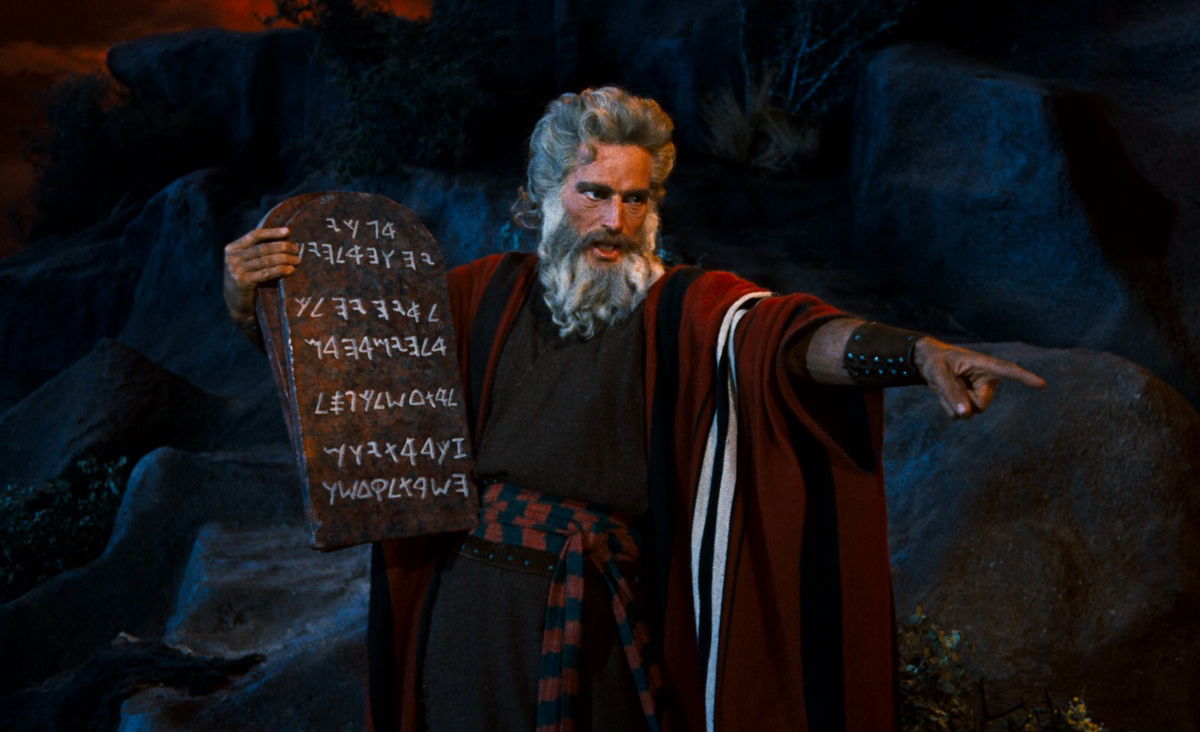

Near the end of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), Moses climbs Mount Sinai to receive the tablets of the Decalogue from God. He then descends the mountain, only to find the ungrateful Israelites immersed in wild pagan worship of the golden calf.

DeMille was hardly the first to render the stunned and furious image of Moses clutching the twin tablets, their message of the one God preemptively repudiated by its intended recipients, as the defining moment of the Sinaitic experience. Countless artists have done the same. Nor, at least at first glance, does that image seem to stray far from the biblical text. Yet I’d like to argue that it radically flattens and perhaps even misrepresents the Bible’s story of the revelation at Sinai.

Making sense of that story is admittedly complicated by its discontinuous and somewhat convoluted narration. The bulk of it appears in this week’s Torah reading of Yitro (Exodus 18-20), but then the narrative abruptly breaks off, resuming four chapters later before breaking off again, and finally picking up and concluding with the episode of the golden calf and its aftermath in chapters 31 through 34. To make matters even more complex, a slightly different version of the narrative is given at the beginning of Deuteronomy—again spread out over several chapters with interruptions, and in less than precise chronological order.

But let’s begin with our parashah. In Exodus 19, the Israelites, having miraculously escaped from Egypt and experienced the even more miraculous splitting of the Red Sea, encamp in the wilderness of Sinai next to a mountain. At this point God has Moses deliver to “elders” of the people the outline of His promise to them: “if you will obey Me faithfully and keep My covenant, you shall be My treasured possession among all the peoples.” To this, the people—“as one”—enthusiastically respond by saying, “All that the Lord has spoken, we will do.”

Reporting the people’s words back to God, Moses is then instructed to explain to the Israelites how they must prepare for their encounter with the divine: they are to remain ritually pure, to wash their clothing, and to maintain a safe distance from the mountain. After three days of preparation, the people gather at the foot of the mountain to await God.

The revelation itself begins with “thunder (kolot), lightning, and a dense cloud upon the mountain, and a very loud blast of the horn.” Soon the entire mountain is engulfed in smoke, “for the Lord had come down upon it in fire,” and the people, as well as the mountain, are described as trembling in fear. Moses then says something to God, and God answers him “in a kol,” a Hebrew word that could mean either a voice or, as above, thunder; neither utterance is reported.

After this initial revelation, Moses is called to ascend the mountain alone and is then sent back down again to warn the people not to approach too close to the mountain. There is no mention of tablets. At that point God explicitly “speaks” the Ten Commandments themselves, which we can presume are the partial contents of the covenant to which the people of Israel have just promised to adhere.

The text thus seems to describe two components to the revelation: the first is wordless, the second is what the Torah itself calls the “ten sayings” or the “ten utterances,” as if to emphasize its verbal nature. The precise sequence, however, remains unclear, as does the relationship between the two components.

To help resolve these textual ambiguities, let’s look at how Rashi (1040-1105), the closest of close readers, interprets the passage quoted above in which Moses first relays the terms of God’s covenant to the people and they give their enthusiastic consent. It continues:

And Moses brought back the people’s words to the Lord.

And the Lord said to Moses, “I will come to you in a dense cloud, in order that the people may hear when I speak with you and so trust you ever after.” Then Moses reported the people’s words to the Lord, and the Lord said to Moses, “Go now to the people and warn them to stay pure. . . .”

Note, first of all, the contradiction in God’s description of the coming revelation: His speaking will be done “with” Moses yet the people are still meant to “hear” it. Rashi understands this to mean that Moses will be the intermediary for all further revelations: the people will hear that God speaks to Moses, and therefore trust in him; Moses will then convey the divine word to them.

What poses a greater problem for Rashi, but also helps him resolve the contradiction, is the repetition of the phrase “Moses reported the people’s words to the Lord.” The first occurrence quite clearly refers to the people’s affirmation of the covenant. Therefore, Rashi reasons, the second occurrence must refer to something else, and he turns to a midrash to suggest what that something is:

There is no comparison between one who hears [a command] from the mouth of a messenger and one who hears from the mouth of the king. [The people said], “We want to see our King!”

In other words, the people have demanded an unmediated experience of revelation. And God concurs, for immediately afterward He issues the instructions about the three-day preparation for the revelation—a preparation that might have been unnecessary if a less direct, and less intense, experience awaited them.

To make sense of this exegesis we have to look a bit further ahead to where the people, after trembling in fear at the display on the mountaintop, beg Moses’ intercession:

All the people saw the thunder, and the lightning, and the sound of the horn, and the mountain in smoke; and when the people saw it, they trembled and stood far off. And they said to Moses, “Speak you with us, and let us listen, but let God not speak with us, lest we die.” (20:15-17)

Without getting into the hermeneutic details, it appears that, in Rashi’s reading, the real sequence of events is as follows: first the people request direct revelation. Then they prepare themselves, and God comes down to the mountaintop in thunder, lightning, and a cloud, and proceeds to utter the first two commandments for all the people to hear: “I the Lord am your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt,” and “You shall have no other gods beside Me.” These are the only two commandments in the Decalogue where God speaks in the first person; the rest refer to Him in the third person. And that is the point at which the people, terrified and overwhelmed by the experience, ask Moses to be their intermediary. God sympathizes with their request and delivers the remaining eight commandments to Moses alone, who then relays them to the people.

Thus, for Rashi, there is no initial, entirely wordless encounter; rather, the “voice” in the first revelation speaks the words of the first two commandments. But he still reads the theophany as comprising both a direct, mass revelation and a slightly more removed verbal and legalistic version via Moses. And others agree. The great Catalonian exegete Moses Naḥmanides (1194-1270) likewise emphasizes the contrast between the verbal and nonverbal, direct and indirect elements of the narrative.

By finding in the events at Sinai both a direct revelation from God to the Israelites and a revelation mediated by Moses, Rashi hits upon one of the fundamental tensions at the heart of the book of Exodus.

One message, seen in the retreat from God’s unmediated revelation at Sinai, is that direct contact between God and the world can be not only overwhelming but positively dangerous. And it’s not just physically dangerous, as implied by the people’s whimpering “lest we die” and numerous other passages throughout the Bible, beginning with Moses’ encounter at the burning bush. There is also a theological danger: an all-encompassing encounter with the divine can lead people to lose sight of specific religious imperatives or even of the distinction between God and the world in which He has revealed Himself, with a consequent retreat into pantheism. Such a confusion might explain the Israelites’ frenzied willingness to ascribe divinity to a golden calf when Moses again ascends the mountain, this time to receive the tablets, and appears to linger there interminably.

There is also an ethical danger. The Talmud states that when God gave the Jewish people the Torah at Sinai, He “suspended the mountain over them like a barrel [and] said: ‘If you accept the Torah, then good; if not, this will be your grave’” (Sanhedrin 77a). In the face of such terror-inspiring revelation, free choice becomes moot, resulting in the loss of moral autonomy.

But there is danger in the opposite message as well. An entirely transcendent God who gives directions only in the form of laws articulated by intermediaries runs the risk of seeming impossibly distant and cold. How then are mere human beings, fallible by God’s own design, to sustain a covenantal relationship with Him? Although built on a foundation of revelation, which by definition is beyond reason, this hyper-rationalist conception of God fails to consider or account for the many other dimensions of the human experience of the divine.

The virtue of Rashi’s interpretation of the theophany at Sinai is that it contains elements of both an intimate, direct, and almost physical encounter with God and a more removed and abstract experience that takes place primarily through God’s words. The Torah, in its depiction of its own revelation, thus becomes a kind of blueprint for how to solve the age-old paradox of a transcendent God who is nevertheless simultaneously involved with the world and somehow immanent within it.

For Cecil B. DeMille, the revelation at Sinai was a purely solitary affair. Charlton Heston’s Moses ascends the mountain on an individual spiritual quest; he hears the Ten Commandments as the Israelites are preparing to worship the golden calf. The scene certainly captures part of the biblical narrative, but it ignores entirely the collective and communal aspect of the moment, as well as the tension between the people’s desire for direct knowledge of God and their quite correct fear of what such knowledge entails. It also ignores the all-important prelude to the revelation: the covenant between God and Israel, for which Moses is nothing more than a go-between.

The communal aspects of the story depend on a Jewish people unified by the bonds of nationhood. When the people accept the covenant for the first time, they become, as we saw, an indivisible unit; they answer God “as one.” As for the two commandments communicated directly (in Rashi’s reading) by God to the Israelites, they involve, first, the acknowledgment that God took them out of Egypt and, second, the prohibition of polytheism. Even today, Jews with the weakest and most attenuated habits of Jewish observance often find themselves attending a Passover seder—and, whatever their actual beliefs or lack of belief, they also tend to be innocent of polytheism. They thereby might be said to retain some connection with the Jewish people as a collective, and to the distinct historical memory that goes with it. Not all of Mosaic law may exercise the same grip on the Jewish sensibility at all times, but an advantage might well inhere in having once heard something directly “from the mouth of the King.”

More about: Golden calf, Hebrew Bible, Moses, Religion & Holidays