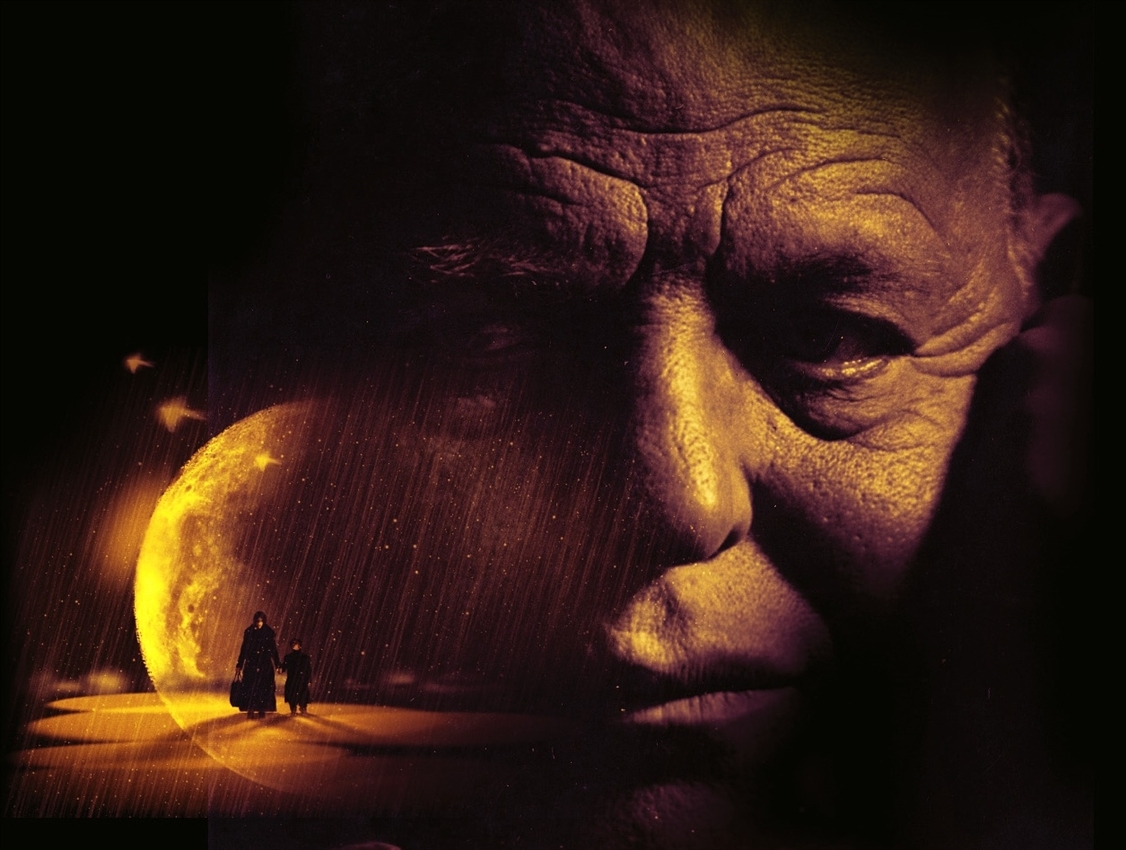

From Bialik, King of the Jews.

A boy walks with his mother at night. Behind them looms the moon, impossibly huge. Trees stream by as if beamed from the headlights of passing cars, followed by the humps of shtetl houses and Jews at prayer in fur hats. As violins swell, the boy is borne forward upon a forest of Hebrew words.

With this animated sequence we enter “Bialik, King of the Jews,” a Hebrew-language film that can now be viewed with English subtitles. It is the third installment in a planned series of twelve documentaries by the Israeli director Yair Qedar, each devoted to a different figure in the history of Israeli literature. The first, a luminous treatment of the writer Lea Goldberg (1911-1970), was released in 2011, followed by a somber exploration of Yona Wallach (1944-1985), Israel’s favorite poetic rebel and lost soul. All three blend animation and music with commentary and archival footage to create powerful, distinct portraits.

Qedar’s broader project is to dramatize the fashioning of a national Jewish literature from its 19th-century East European roots to its flowering in the land and state of Israel, a literature rooted in the Hebrew tradition yet also secular and modern. And in this story, the towering inaugural figure is indisputably Haim Nahman Bialik (1873-1934), both a pivotal force in the creation of modern Hebrew culture and himself one of its myths. In the words of the scholar (and Knesset member) Ruth Calderon in the film: “The British have Shakespeare, the Germans have Goethe, the Russians have Pushkin. The Jews have Bialik.”

Yet of all the subjects in Qedar’s series, Bialik may also be the most challenging to capture. Psychically complex, possessed of a slippery personality, he is somehow both everywhere and nowhere in Jewish culture today. In his own lifetime, the mantle of national poet lay heavily, even stiflingly, upon him, and he often felt torn between his public role and his private desires. Most Israelis know his children’s verse from their elementary-school days, but even in that guise he presents difficulties: Bialik, who was born in a small Ukrainian village and would move to Palestine only in 1924, wrote mostly in the accent-and-pronunciation patterns of East European Hebrew, considerably different from the way Israelis speak their language today.

Bialik’s formative childhood experience was the death of his father, a tavern-keeper, when he was still a boy, and his subsequent banishment to be raised by relatives. While a student at the famed Volozhin yeshiva, a talmudic academy that seems to have incubated as many secular writers as rabbinic scholars, he began writing poetry. By 1900, when he moved to Odessa, then the capital of modern Hebrew literature, he had already earned a reputation as the foremost young Hebrew writer of his day.

In 1903, during the wave of pogroms sweeping through Russia, the then thirty-year-old Bialik was sent to gather information about the horrific massacres and mass rapes that had taken place in the city of Kishinev. “In the City of Slaughter,” his best-known and most shocking poem emerged from this experience. Refusing any note of either lamentation or consolation for the devastation and suffering of the Kishinev Jews, and ignoring his own investigative evidence of their attempts at self-defense, “In the City of Slaughter” portrays them as cowards and their political situation as both intolerable and irremediable.

Circulated widely in Russian and Yiddish translations, Bialik’s poem has been credited with spurring a turn toward active self-defense among the young generation of Zionists—though in fact it nowhere calls for such action and is marked by an almost nihilistic despair. “Your dead were vainly dead,” proclaims the unredeeming God of “In the City of Slaughter,”

and neither I nor you

Know why you died or wherefore, for whom, nor by what laws;

Your deaths are without reason; your lives are without cause.

What says the Shekhinah? In the clouds it hides

In shame, in agony abides;

I, too, at night will venture on the tombs,

Regard the dead and weigh their secret shame,

But never shed a tear, I swear it in My name.

(trans. A. M. Klein)

Until he moved to Palestine at age fifty-one, Odessa and then Germany became the centers of Bialik’s prodigious literary and cultural activities. In addition to poetry, he produced short stories, seminal essays on literature and culture, and groundbreaking translations from European literature into Hebrew. He created, for the first time, a children’s literature in Hebrew: songs, folktales, lullabies. (Jewish parents around the world still rock their babies to his see-saw ditty, Nad-ned.) With the writer Y. H. Ravnitzky, he produced the Book of Legends, a magisterial compendium of rabbinic literature organized by theme: a work that, as much as his poems, is emblematic of his project of refashioning traditional materials for use in a secular nation-state.

It is estimated that Bialik’s funeral in Tel Aviv was attended by 100,000 mourners. At the time, this might have represented a majority of all Jews in the world for whom Hebrew was their first language.

Qedar’s film traces the arc of this career, including its darker interstices: Bialik’s childlessness, the long poetic silence that lay upon him later in his life, his thwarted relationship with the artist Ira Jan. (This last, revealed only after the poet’s death, is the basis for another recent Israeli movie, Aviv Talmor’s faux-documentary, I Am Bialik, whose protagonist decides he is the descendant of Bialik’s and Jan’s almost certainly never consummated affair.) In the film, an all-star roster of scholarly talking-heads, including Dan Miron, Ariel Hirschfeld, and Avner Holtzman, provides engaging commentary, and the exquisite singer Ninet Tayeb accompanies with musical renditions of such poems as Hakhnisini tahat kenafeikh, “Bring Me Under Your Wing.” “The stars lied to me,” appeals the poet to his yearned-for lover/mother/divinity (in my translation):

There was a dream, but that died too.

Now I have nothing left in the world,

Nothing at all.

Bring me under your wing.

Be a mother and a sister to me.

Let your lap be haven for my head,

A nest for my rejected prayers.

Created for an Israeli audience, the film at times lacks the sort of context—for instance, about the evolution of modern Hebrew, the history of Zionism, and the budding Jewish state in Palestine—that would likely be helpful to American viewers. Yet this doesn’t lessen its impact, which in any case relies less on our being told what to think than on conveying an impression of the force of the poetry. This is aided greatly by the narrators (Orna Fatussi and the actor Chaim Topol) and by the animation, as when the individual letters of a poem dissolve into the silhouettes of harvesters in a Ukrainian potato field. Photographs of the poet, who in later life bore a striking resemblance to Anthony Hopkins, stare soulfully at us throughout.

Like Qedar’s project as a whole, this film implicitly raises questions about the nature and viability of a secular Jewish culture. As we learn, Bialik was regarded as a kind of secular guru, the “rebbe of Tel Aviv,” a culture hero who seemed to proclaim the possibility, enabled by Zionism and the Hebrew revival, of a Judaism beyond religion. In some moments, indeed, Bialik did hold that the Hebrew word itself, even stripped of its traditional context, was the repository of mythic energies that the modern, secular writer could unleash. Qedar’s earlier film about Yona Wallach shows the danger of such rootless romanticism taken to its extreme.

Yet the ever-complex Bialik was also a passionate advocate of the conviction that modern Jewish culture, in order to thrive, must be rooted in the soil of the past. Bialik, King of the Jews circles sympathetically around this ongoing tension without resolving it, and thereby invites a new generation to bring the poet under our wing.