Isaac Bashevis Singer in the 1980s. Bernard Gotfryd/Getty Images.

We present here the ninth chapter from the memoirs-in-progress of the renowned scholar and author Ruth R. Wisse. Earlier chapters can be found here. Further installments will appear over the next months.

In the fall of 1972, upon returning to Montreal from our failed attempt to settle in Israel, I resumed my academic duties teaching Yiddish literature at McGill. With three children at home, I was faced with the common need to balance home and profession. The child who slices his thumb with a penknife, grabs hold of a cactus, or breaks her leg jumping from a snow pile—none of these examples is hypothetical—requires placing the exigent claims of motherhood over the otherwise hallowed obligations of teaching. To this day I regret the times I postponed celebration of Billy’s birthday because it coincided with the annual conference of the Association for Jewish Studies. But as I taught only three days a week, balance was generally a matter of planning and timing.

As for setting professional priorities, when I began teaching Yiddish literature I was still so frustrated by the college professors who had lectured us out of their ancient notes that I tore up mine at the end of every school year lest I ever be lured into following suit. Though I enjoyed research, I vowed not to write books at the expense of teaching, and never to give the same lecture twice. Fortunately, after a few years I realized that one could replenish used material instead of starting each time from scratch.

Of course, on any given workday I still had to choose among reading primary works in Yiddish or secondary sources on literature, writing academic articles, and preparing classes. But this was mostly a matter of prioritizing, and it still left time for musing on when and whether I would dare to try becoming an intellectual and writing for Commentary.

I.

Maybe because “intelligent” was the most prized adjective in my childhood—in Yiddish, inteligént with a hard “g”—I valued the work of “intellectuals” before knowing what they actually did. The term took shape for me as a form of thinking that flows from reading yet differs from erudition. My original model was the talk around our dining table that began in my teens, where the primary text was indeed often Commentary, the only publication that our father, my older brother Ben, and I regularly read in common.

That the magazine was also important to others in Montreal I learned one day in the late 1960s when I happened to meet my old elementary-school principal Shloime Wiseman at a public lecture and he asked me, out of the blue, “What do you make of Cynthia Ozick’s attack on Yiddish!?” Wiseman was assuming that I had read that month’s Commentary, where the lead item was a full-length novella by Cynthia Ozick.

“Envy; or, Yiddish in America” is a brilliant study of Yiddish writers in New York, one of whom breaks through to international renown while most of the others languish in more or less bitter obscurity. Wiseman, who could identify some of the writers on whose jealous competitiveness the story was founded, thought it bordered on anti-Semitism. I tried to persuade him it was not against Yiddish but an affectionate study of what Yiddish in America was up against.

Ben had begun subscribing to Commentary in the early 1950s, so that by the time I was in college I was familiar with the names Milton Himmelfarb, Will Herberg, Lucy Dawidowicz, Irving Kristol, Nathan Glazer, Dan Jacobson, and what seemed like an army of thinkers. I was eager to join their ranks. In my senior year, mild praise for one of my assignments in Hugh MacLennan’s creative-writing class prompted me to send it to the magazine—minus the obligatory return envelope as if to signal my serene confidence that it would be accepted.

The story, big surprise, was about a Jewish college senior who accompanies her parents to an evening commemorating the April 1943 uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto and then goes home to complete the paper she is writing on the German poet and playwright Heinrich von Kleist. Far too subtle to attempt an actual plot, I believed the girl’s implied re-creation of the impossible tension between the allure of German high culture and the fact of Germany’s murder of the Jews would emerge by itself. The rejection letter stung; in later years, I winced at how puerile my submission must have seemed to the editors.

As an example of what Ben and I found exciting in Commentary, consider this 1964 item by the psychiatrist Leslie Farber—not to be confused with the cultural critic Leslie Fiedler who also wrote for the magazine. “I’m Sorry, Dear” opens on a dialogue between two unidentified individuals, of whom the male speaks first. (Ben and I were both already married when this appeared):

Did you?

Did you? You did, didn’t you?

Yes, I’m afraid I—Oh, I’m sorry! I am sorry. I know how it makes you feel.

Oh, don’t worry about it. I’m sure I’ll quiet down after a while.

I’m so sorry, dearest. Let me help you.

I’d rather you didn’t.

But, I. . .

What good is it when you’re just—when you don’t really want to? You know perfectly well, if you don’t really want to, it doesn’t work.

But I do really want to! I want to! Believe me. It will work, you’ll see. Only let me!

Please, couldn’t we just forget it? For now the thing is done, finished. Besides, it’s not really that important. My tension always wears off eventually. And anyhow—maybe next time it’ll be different.

Oh, it will, I know it will. Next time I won’t be so tired or so eager. I’ll make sure of that. Next time it’s going to be fine! . . . . But about tonight—I’m sorry, dear.

Disquieting as it was to see sex discussed so frankly in what we treated as a family magazine, we were intrigued by the article’s reflections on the (William) Masters and (Virginia) Johnson experiments in sexology. Actually, Farber was less interested in the dubious reliability of the science than in how the setting of explicit standards for female orgasm and simultaneous male ejaculation had inhibited romantic ideals of intimacy and love. Technical mastery, he wrote, tempts humans with visions of omnipotence while exposing their fundamental and irreversible mortality.

Moving from the physical to the metaphysical, the essay throbbed with larger anxieties:

[The] manner in which lovers now pursue their careers as copulating mammals—adopting whatever new refinements sexology devises, covering their faces yet exposing their genitals—may remind us of older heresies which, through chastity or libertinism, have pressed toward similar goals; one heretical cult went so far as to worship the serpent in the Garden of Eden. But the difference between these older heresies and modern science—and there is a large one—must be attributed to the nature of science itself, which . . . by means of its claims to objectivity can invade religion and ultimately all of life to a degree denied the older heresies. So, with the abstraction, objectification, and idealization of the female orgasm we have come to the last and perhaps most important clause of the contract which binds our lovers to their laboratory home, there to will the perfection on earth which cannot be willed, there to suffer the pathos which follows all such strivings toward heaven on earth.

Even when I did not fully understand the argument of an essay like this—the fault presumably mine—I saw the way it peeled open a subject or wrestled a subject to the ground or otherwise probed or amplified it in pursuit of a finding that could rarely be inferred at the start but seemed inevitable and proved by the end. A lovers’ dialogue that could have been played for laughs by Mike Nichols and Elaine May (the stand-up duo whose clever skits were also an occasional subject at our dining table) expands into a meditation on the dangerous hubris of the rational intellect.

That’s how I wanted to write, but I wasn’t sure I ever could.

Hands down, the Commentary essay that disturbed us most was Norman Podhoretz’s “My Negro Problem and Ours,” published in 1963 at the height of the American civil-rights movement. We were hardly unique in our reaction, since the essay brought the magazine several hundred letters (including one from Ben).

On the basis of hard-won experience as a Jewish kid in Brooklyn stalked and bullied by bigger black boys, Podhoretz—who in 1960 had become the chief editor of Commentary at the age of thirty—challenged prevailing stereotypes of rich Jews versus persecuted Negroes, unearthing in himself emotions like envy and hate that, he was certain, characterized the “twisted and sick” feelings most American whites harbored against blacks—who heartily returned the compliment.

Rather than defending himself against presumptive charges of racial prejudice, Podhoretz admitted these feelings for the sake of a larger argument: that, contrary to the facile belief of many liberals, relations between blacks and whites were so tortured as to negate altogether the dream of amicable co-existence any time soon. Fiercely following his logic to the end, he concluded that the only way of resolving the underlying problem, and even then only incrementally, was racial intermarriage. “I believe that the wholesale merging of the two races is the most desirable alternative for everyone concerned.” And then, since ideas, to be persuasive, had also to undergo the test of personal honesty, he asked himself in print whether he would like one of his own three daughters to “marry one.” No, he answered, he would not like it at all, but he would accept it as the man he had “a duty to be.”

This masterpiece of political incorrectness has lost none of its bite, as I would learn on the several occasions that I included it in a college course. What troubled our family back then in Montreal, however, was not the essay’s contentious treatment of race, which hardly resonated on our side of the Canadian border, but something else entirely: Podhoretz’s apparent indifference to whether his daughter’s hypothetical black suitor was Jewish. So the boy was black, we said; big deal. But how could the editor of a Jewish magazine treat so casually his daughter’s marriage to a Gentile?

True, the Jews made an appearance in the essay. Imagining himself in the position of blacks despairing of the utopian vision of a society in which color would cease to matter, and driven by that despair to wonder whether their survival as a group was worth the struggle demanded of them, Podhoretz added this analogous thought, almost as an aside:

In thinking about the Jews, I have often wondered whether their survival as a distinct group was worth one hair on the head of a single infant. . . . Did the Jews have to survive so that six-million innocent people should one day be burned in the ovens of Auschwitz? It is a terrible question and no one, not God Himself, could ever answer it to my satisfaction.

I found this question terribly wrong. The genocide of the Jews was the consequence not of Jewish survival but of Nazism’s perverted definition of the “fittest.” Should the Jews, having been forcibly made aware of the extravagant price of their survival, now surrender—for example, through miscegenation with Gentiles—because they wanted to solve the problem of anti-Semitism? If God did not flinch after the book of Lamentations, why would He flinch after the ovens of Auschwitz?

All of this may be enough to suggest how Commentary captivated and provoked us to argument. But I did not yet take up the challenge, and by the time I came to know the authors of these and other articles on matters of particularly Jewish concern, they themselves had come to regret some of the things that had bothered me in the late 1950s and 60s. Nathan Glazer, for example, later wondered why, in the era before, during, and after the Holocaust. Partisan Review, a magazine created in large measure by Jewish editors and writers, “had so little to say about Jews, Jewishness, or Judaism.” Sidney Hook’s 1987 autobiography would cite the underestimation of Zionism as one of the two great miscalculations of his generation (the other was underestimating capitalism). Once Norman Podhoretz took up the cause of Israel, moreover, no one ever defended it more effectively.

By the 1970s, as is well known, Commentary had thrown its intellectual resources behind the reorientation that Irving Kristol would immortalize in his definition of the neoconservative as “a liberal who has been mugged by reality.” My veneration of these thinkers was tempered only by disappointment at how long it took them to get there. I seem to have been a neoconservative-in-waiting.

II.

The first member of the Commentary circle I met and befriended was Neal Kozodoy, less than a year after he had joined its editorial staff. During McGill’s winter break in 1966-67, I attended a student Zionist conference at a kosher lakeside hotel in the Laurentian mountains north of Montreal. Though I was then still a graduate student teaching a section of freshman English, Richie Cohen, one of the student organizers, invited me to serve as resident academic, and we drove up together to Ste. Agathe where the conference was being held. Neal was brought in from New York as a speaker. He was not much older than the student participants and was still also pursuing his own graduate work at Columbia, but his lecture about the image of the Jew in modern literature displayed the verve I associated with the best of thinkers. He was intimidatingly smart.

The informality of the conference gave us time to talk about the magazine. Very gingerly, I complained about what I saw as its failures of omission on matters Jewish and Zionist. I must have somehow gotten the impression that Neal may have shared some of my misgivings. But if so, he did not let on, and we moved to other subjects.

While majoring in English literature at Harvard, Neal had also attended the Hebrew College of Boston, spent a year studying in Jerusalem, and at Columbia written a Masters’ thesis on the Hebrew poets of medieval Spain. Around the time I met him, he had already become a “go-to” freelance editor in Jewish publishing for books like Elie Wiesel’s The Jews of Silence and Abba Eban’s My People: The Story of the Jews. As I was then writing my doctoral dissertation on the figure of the schlemiel, under an adviser whose expertise in modern fiction did not extend to Jewish languages, it was delightful to speak with this clued-in figure who demanded clarification of my inchoate ideas and suggested readings and approaches I hadn’t thought of. The ensuing improvements to my dissertation made up for the damage to my ego.

Unlike Norman Podhoretz, Commentary’s prolific editor-in-chief, Neal rarely wrote under his own name, evidently preferring to compose through the writers and works he edited at the magazine and outside it. One of those outside projects became a series of books published by Behrman House and intended for use in the then-forming field of Jewish Studies. (Among the early titles were Isadore Twersky’s A Maimonides Reader, Michael A. Meyer’s Ideas of Jewish History, Lucy Dawidowicz’s A Holocaust Reader, and Robert Alter’s Modern Hebrew Literature.) He invited me to edit a volume geared to courses like those I was teaching on Yiddish literature in English translation.

Mine would emerge as an anthology of short fiction, A Shtetl and Other Yiddish Novellas, bringing together various literary representations of the East European Jewish market town. When offered the choice of a 10-percent royalty on prospective sales or a flat fee of $5,000, I declined Neal’s advice and chose the former. Indulging every novice’s fantasy, I foresaw legions of professors of politics, let alone literature, adopting my reader for their classrooms, and expected someone (maybe Costa-Gavras?) to buy the film rights for one novella in particular—about a strike by Polish Jewish workers that escalates into internecine violence—thereby sparking mass demand for the book. Today, after three subsequent editions, the volume still hasn’t brought me close to that lump sum, yet I’d probably make the same choice again, in the firm belief that what interests me will eventually garner the attention it merits.

It was likewise thanks to Neal that, before I’d worked up the courage to try to write for the magazine, I first visited the Commentary offices on a trip to New York. Yiddish literature is filled with reports of the first visit paid by aspiring writers to the home of the great Y.L. Peretz, there to offer homage and, perhaps, be invited to show their work. One such acolyte records pocketing Peretz’s discarded cigar as a keepsake and being mortified when it starts burning a hole in his vest. Another, who had borrowed a cape to cover his torn trousers, is at the point of leaving when he is slipped some money by his perceptive host and told to buy a new pair. A third is advised to forget his choice of writing in Hebrew and switch to Yiddish instead (though Peretz himself wrote in both languages).

These anecdotes aptly convey my own provincial excitement at getting to meet Commentary’s editors on the seventh floor of the American Jewish Committee’s building on East 56th Street. Although I had secured a university appointment, a goal that some of the magazine’s earlier editors had aspired to, I considered theirs much the higher accomplishment.

Marion Magid was Commentary’s wise-cracking associate editor, her sassy voice and sinewy figure reminiscent of Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday and Katharine Hepburn in Woman of the Year. You haven’t appreciated the art of the book review until you read hers of Jewish Wit by the then well-known Freudian psychoanalyst Theodor Reik (1962):

The book has apparently not been edited at all, leaving Dr. Reik’s incredible prose Style intact. There is a fresh surprise on every page. No sooner has the reader built up an immunity to the continuous present, the Germanic inversion (“Late resounds in us what early sounded”), and the mangled citation (“Be Kent unmannerly when Lear is crazy”) than he is faced with new challenges: “While he still lived in Germany, he identified with his Jewish friends and emigrated to America.” In the end it becomes a game and there are rich incidental rewards: women who are “chase and virtuous”; a man who “spoilt his changes in life”; “the saving grave of the Jewish people.” (Has no one read the gallows?)

On a later visit I would receive my own (jovial) slashing when I turned up in the doorway of Marion’s office wearing my favorite navy-blue shift. Among my idiosyncrasies was the conviction, not shared by my husband, that vestal clothing was sexier by virtue of the mystery it concealed. Marion took one look at me and declared, “Oy, it’s Hashomer Hatsa’ir!” It broke me up to be consigned to the sartorial brigades of a Marxist Zionist youth movement that eschewed bourgeois accoutrements like lipstick and marriage. Being the target of Marion’s wit made me feel almost like an insider.

Norman Podhoretz’s office was protected by a secretary, but he was wonderfully cordial when I gained admittance. Over time he taught me to accept hostility as an inevitable reward for exposing unwelcome truths. This is the man who would write, “If I wish to name-drop, I have only to list my ex-friends,” and for whom it was a point of honor to speak out against rotten ideas even at the cost of social disadvantage. His instruction was the more admirable since, when I met him, he was already losing the kind of celebrity the pursuit of which, in his recently published Making It, he had called “the dirty little secret” of the New York intellectuals—that is, his own community.

At the time, I had less interest in the book’s thesis than in being liked myself, an interest manifested in a reluctance to offend even those who offended me. I tried to learn from Norman—and from Neal’s example—not to fear dislike or to avoid confrontation. What sometimes looked like courage was in my case an imitation of its practitioners.

III.

By 1976, when in addition to Yiddish I had begun teaching courses at McGill on American Jewish literature, Neal invited me to write a review essay for Commentary on three new works of fiction in the latter field. One of them was by Cynthia Ozick of “Envy” fame, who had recently taken to foretelling the emergence of an authentic Jewish culture in the English language. She had described this “new Yiddish” through the image of the shofar, the curved ram’s horn that is sounded during the Jewish Days of Awe: “If we blow into the narrow end of the shofar,” she wrote, “we will be heard far. But if we choose to be Mankind rather than Jewish and blow into the wider part, we will not be heard at all.”

Although I thought this a brilliant metaphor for an affirmative and resonant mode of Jewish particularity, I was not yet persuaded that the new cultural amalgam was really emerging. The review would put her augury to the test. Pitched as a piece of literary history, “American Jewish Writing: Act II” contrasted the so-called triumvirate of Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and Philip Roth, each of whom bridled at being labeled “Jewish,” with the three newer writers under review: Norma Rosen, Hugh Nissenson, and Ozick herself.

Each of their books had tackled, through fiction, a distinctly Jewish issue. Much as I wanted to cheer their success, I did not find the artistic results as successful as I’d hoped to. In part, I thought, the reason lay in the still relatively impoverished cultural ground of mainstream Judaism in America—a circumstance, I pointed out, that forced writers intent on engaging meaningfully with Judaism to situate their plots elsewhere: in Israel, in the Jewish past, in an ultra-Orthodox community. American Jewish life did not yet supply a rich enough context for the intensity the three authors were seeking, and their books reflected the strain of the effort.

The three took offense at my essay and attacked my credibility. I had not known that they were friends. In a letter-to-the-editor, Cynthia charged me with reading literature as “sociological reality,” and said that I had demonstrated “an essential disbelief in fiction as fiction.” Her letter possessed all the verve I appreciated when her displeasure was directed at others:

The light-years distance between a cultural critic and an imaginative writer is made most explicit in Ruth R. Wisse’s argument that “for those who take Judaism seriously as a cultural alternative, the wish to weave new, brilliant cloth from its ancient threads, the sociological reality of the present-day American Jewish community would seem to represent an almost insurmountable obstacle.”

As I had no intention of becoming an “imaginative writer” of fiction, I held to my view that for the time being, American Jewish reality lent itself more easily to satire, nostalgia, or fantasy than to the serious probing of Jewishness. The point she called sociological was not meant to limit the capacities of a novelist, but to note that a new Yiddish—her coinage and dream—was likely to arise only among the Modern Orthodox Jews who were still somewhat outside the mainstream. While Yiddish writers coped with the erosion of their culture, those writing in English worked with shoots of a Jewish culture that had not yet ripened.

It was painful to find myself at odds with a writer I greatly admired and would have wanted to befriend; fortunately, Cynthia seemed to bear me no grudge. We eventually became long-distance friends and, as I will describe in a later chapter, comrades-in-arms against the enemies of Israel. She was herself no slouch as a “cultural critic”—I rated one knockout op-ed of hers worth ten of mine—but it was easier for me to take unpopular positions since I was more than satisfied writing for Commentary. Professional writers were well advised to stay in the good graces of the PEN association and the editors of left-leaning magazines.

IV.

But I have gotten ahead of myself. By the time I debuted in Commentary I was twice as old as when I had sent in my first unsolicited story, and though I was reviewing books and writing about literature, I still looked to others to say what was most on my mind. One day, I found myself urging a colleague in Jewish Studies to write an article about an issue then heating up in the Jewish community. “You might want to say,” I began, and outlined the points he could make as he listened with interest.

Suddenly, as I was talking, I realized that this admirable scholar would never write the article I had in mind, and certainly never write it as I thought it should be written. I felt silly for whatever it was—sloth, fear, childishness—that was holding me back. I had borne my own children but here I was looking for a surrogate to carry my ideas.

If I were now to attempt the kind of self-scrutiny I normally distrust, I would be compelled to note that I did not begin to write for Commentary until after my brother Ben died at forty-three, leaving sheaves of poems and a diary he had started keeping in his late teens. He was survived by three children, a loving wife, stricken friends, and parents, one of whom would soon die of grief. The others mourned, but I was incensed. He had been my guide and shield since earliest childhood, my model of integrity and grit. He was also the buffer between me and our immigrant parents, absorbing their bewilderments, reorienting them in their uncertainties, and reassuring them that all would be well. For as long as I could remember, I had been expecting him to write whatever had to be written.

Let me get this over with so that I can later bring Ben peacefully back into the story. He died of pancreatitis on November 25, 1974. Everyone who knew him was left with a cascade of questions. Why? How? What could have been done? I once would have tried to describe his illness, but I will now only record that at the time I believed that he had had it in his power to live. Simply, I blamed him for dying, held him responsible for his death.

On the day of his funeral I was in a rage. Part of me wept for his poor children and worried for my sister-in-law, but the anger was selfish. “Stupid man, how could you squander a life our parents had gone to such lengths to save? How could you abandon me who needs you so badly?” At the burial, as the gravediggers made ready to fill the grave after the family had dropped their symbolic shovelfuls of earth on the coffin, Ben’s friends waved the men off and insisted on filling the grave themselves according to Jewish tradition. He was the first of their cohort to die. So there we stood in the cold, shoveling the hard ground, who with love and who with sorrow, who with regret and who with wrath. I knew I was being cruel but didn’t care. I hated death and took it personally. It was unbearable to lose Ben and it took me years to calm down.

The colleague I urged to write that article on a similarly bleak November day may have reminded me a little of Ben, but it is wrong to keep picking at this sore. Families are gnarled, death does not come to everyone in his time, and writing isn’t easy. Maybe I waited till I was forty simply because it took that long to gain the understanding I needed. By now more than twice forty, I have still not gotten over the loss of my brother, though at this point I just wish he could be here to enjoy his grandchildren and Israeli great-grandchildren.

V.

But who knows? Had Montreal produced an intellectual circle like the one that sprang up in New York around Partisan Review and Commentary in the 1930s and 40s, I might have fashioned myself an intellectual and published in little magazines. (Ben might have preceded me.) In the absence of anything like it, I chose the same path as several college friends and became a professor, but unlike their path in the social and hard sciences, mine was happily still as open as California in the gold rush.

For my next major project after my dissertation and publication of the resulting book, The Schlemiel as Modern Hero (1971), I wrote about two American Yiddish poets who reached their prime in the 1920s just as the masses of immigrant Jews were abandoning their language. On good nights, these two poets, Mani Leib and Moishe Leib Halpern, came to me in dreams so that when I sat down to write I had only to bring them to life as I had “seen and heard” them talk in the coffee shops of New York’s Lower East Side. The contrast between the two of them, in temperament and in tone, provided the drama of A Little Love in Big Manhattan (1988). In providing context and biography, I was hoping to develop in readers a taste for their poetry, to make it as familiar to others as it was becoming to me.

In fiction I was attracted to strong political thinkers like Mendele Mokher Sforim in his circle and George Eliot in hers. Sholem Aleichem tried to find moral balance where the world supplied none. Yet the more I read and taught literature, the less I trusted Shelley’s boast that poets were the unacknowledged legislators of the world. King David managed to win battles and write psalms, Disraeli to govern and write fiction, and Churchill to save Western civilization and dazzle with his writing and painting—but it was not as artists that they attempted to legislate. Literature could be an amazing repository of truth and/or beauty, but there was no necessary correlation between talent and virtue. A superb mistress did not necessarily make a passable wife or mother.

Quite by chance, I had come to know the Yiddish writer who provoked such questions—the very one who served as the object of “envy” in Cynthia Ozick’s novella about Yiddish in America. And thereby hangs its own tale.

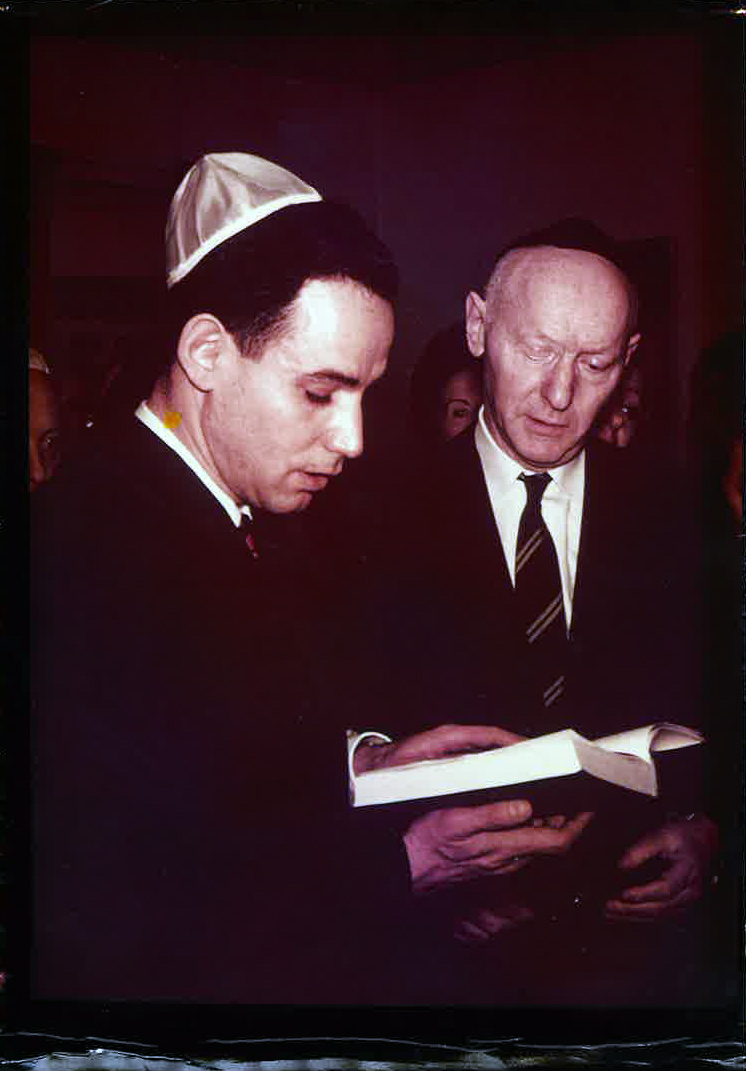

Leonard Wisse (l) and I.B. Singer (r) at pidyon ha-ben ceremony for Billy Wisse, January 1963. Photo by Benjamin Roskies.

When our son Billy was born at the end of December 1962, we showed our gratitude for the gift of this wondrous child by celebrating a pidyon ha-ben, the ancient ceremony in which the father of a firstborn son “redeems” him for five pieces of silver from a member of the priesthood—the kohanim. During my studies in New York I had met the Yiddish book publisher Israel London, who happened to be a kohen, so I took the occasion to phone him and ask whether he might do us the honor of coming to Montreal to serve in that role. “Why me?” London asked. “Bashevis Singer is speaking in Montreal that day. Ask him.”

Bashevis, as I.B. Singer was known in Yiddish, promptly accepted my invitation, saying that although he had never before performed as a kohen, “it could no longer do him any harm” (s’ken mir shoyn nit shatn). On the appointed afternoon, he graciously showed up at our home and kissed my hand like a Polish count. During the brief ceremony (photographed by Ben) he was visibly more nervous than Len in reading his part, and when handed the required coins—new silver dollars Len had gotten from the bank—he timidly asked what to do with them, uncertain whether to accept our assurance that he could spend the money as he liked.

A shy and awkward man, Bashevis resembled the protagonist of much of his fiction, and there seemed to be no way of making him feel at home in this room of Yiddish speakers who delighted in his presence. But he did form a high opinion of our community. In his regular column for the daily Yiddish Forverts (Forward) under the pseudonym Yitzḥak Varshavski, he duly reported “one of my loveliest experiences serving for the first time as the kohen for a pidyon haben” and praised our home for being “filled with Yiddishism in the good sense of the word”—meaning, untinged by socialism. He also cited his rabbinic grandfather’s teaching that the most fortunate rabbi was one whose parishioners were better scholars than he:

Each time I speak [to a Yiddish audience] I am newly persuaded how many intelligent people come out to hear Yiddish lectures. The Yiddish writer and the Yiddish press must reckon with this. We must be careful with every word because we are paid close attention. The expression oylem-goylem [the stupid masses] was always false and cynical, today more than ever. Our audience grows ever more refined, asking questions it is not easy to answer, with no patience for mistakes or empty rhetoric.

A wonderful testimonial—but Bashevis and Varshavski were not alike, or the same person. In his novels, as though telegraphing his own inveterate inconstancy, Bashevis had his leading male characters juggling two, three, or more women simultaneously, and as a public figure he himself courted different constituencies. When appearing on American talk shows he peddled jokes rather than talmudic homilies, and in supervising translations of his fiction he flouted any notion of literary “authenticity” by giving one of his finest novels, The Family Moskat, two separate conclusions, the road to Zion for his Yiddish readers and, for Americans, the figure of Death as the promised messiah.

The latter ending was closer to his instincts. William Blake said of the author of Paradise Lost that “Milton was of the devil’s party without knowing it,” crediting both the poem’s dramatic power and the amoral potential of great literature. Bashevis went Milton one better by writing some of his best works in the voice of the devil.

His cynicism, including about the future of Yiddish and its audience, was boundless. Having translated part of David Bergelson’s novel, When All is Said and Done, I asked Bashevis if he could suggest a likely publisher. His response: “No one is going to read Bergelson.” When I later told him about the first volume in the Library of Yiddish Classics, a series I had launched with Lucy Dawidowicz and a small circle of friends, he dismissed the author, no lesser a figure than Sholem Aleichem, as “sentimental.” He combined his distrust of Communism, socialism, and all ideological substitutes for Judaism with antagonism toward any modified reforms of his parents’ Orthodoxy—which he did not follow. “What is there then?” asks the title character Gimpel the Fool in the most famous of his stories, to which the devil answers, “A thick mire.”

The novelist Dan Jacobson, who otherwise admired Singer, noted how unfairly he “imported” radical evil into depictions of traditional Jewish society where they were explicitly abjured. Why would he have invented scenes of fornication, debauchery, and corruption that he knew had not taken place in the Jewish towns of Poland and Lithuania?

Yet great writers must work within the constraints of their language, and Bashevis had the richest Yiddish of his generation. Writing after Hitler and Stalin, he felt bound to confront the devil’s domain, and since he could do so only in Yiddish, he transformed the moral obsessiveness of Jews like his parents into opposite extremes of dissipation. So I thought he earned his Nobel Prize in literature, and I loved the challenge of teaching some of his morally ambiguous stories.

Still, the cultural critic in me would not yield to the imaginative writer—which made me all the more grateful for writers who did not always confront their readers with that binary choice. Saul Bellow, another Nobel laureate, comes to mind here. In one of my favorites among his novels, Bellow has the eponymous Mr. Sammler say:

[I]t is sometimes necessary to repeat what all know. All mapmakers should place the Mississippi in the same location, and avoid originality. It may be boring, but one has to know where he is. We cannot have the Mississippi flowing toward the Rockies for a change.

Precisely. I aspired to be that reliable mapmaker.