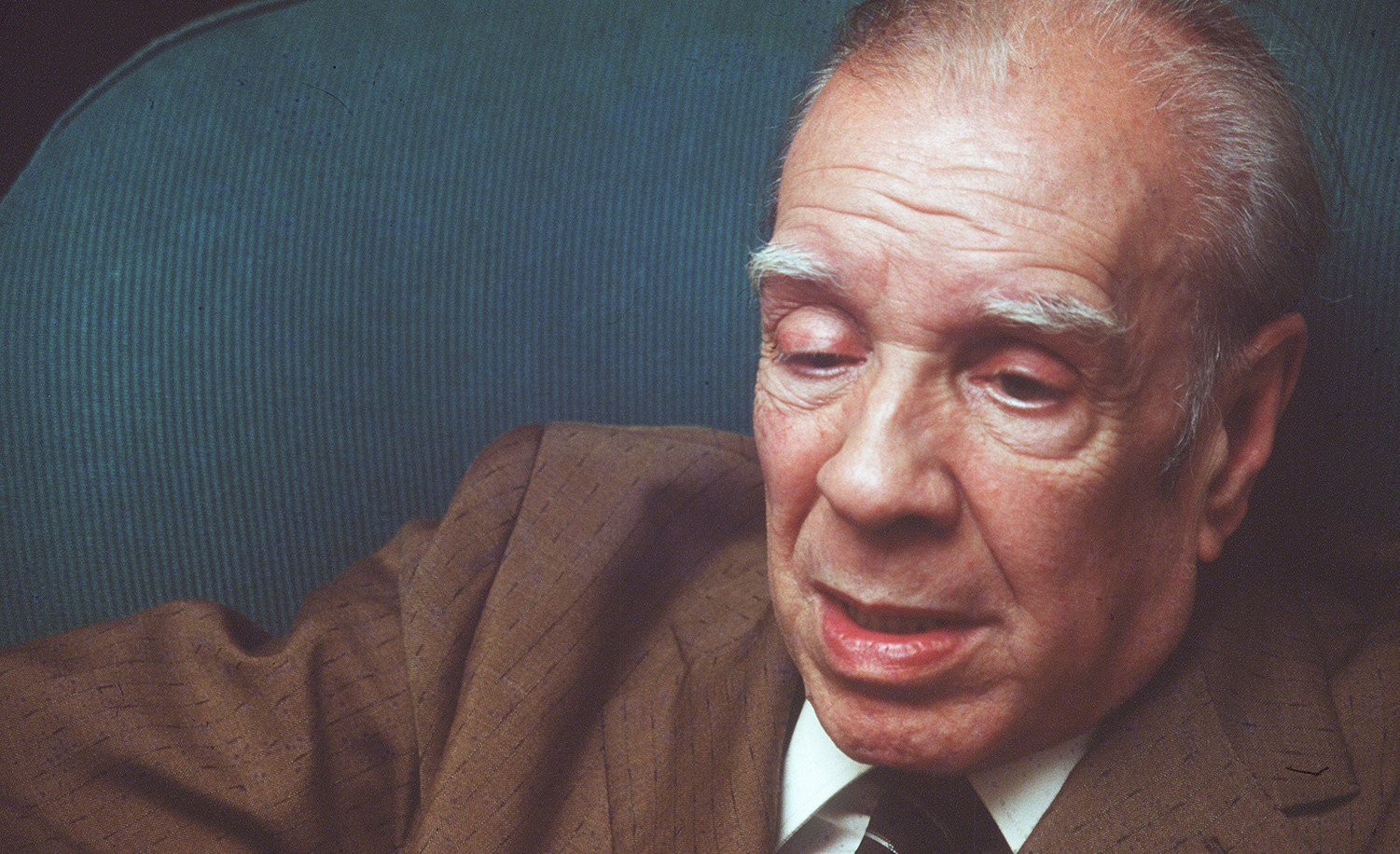

Jorge Luis Borges. Raul Urbina/Cover/Getty Images.

This month, a new Spanish volume was published about Jorge Luis Borges’s relationship to Judaism—timed to be released 50 years after his first visit to Israel at the personal invitation of David Ben-Gurion. The book, titled Borges, Judaísmo e Israel, explores the great Argentinian writer’s various Jewish connections.

A lapsed Catholic with an interest in many religions, Borges (1899-1986) was particularly fascinated by Judaism, especially Kabbalah, and surprisingly erudite references to Jewish texts make their way into several of his stories. Even more unusually for a literary figure, especially one who traveled in avant-garde circles, his appreciation of Judaism translated into enthusiasm for the Jewish state.

Indeed, the 1969 trip to Israel affected Borges profoundly, prompting him to write a trio of poems in praise of the young state and the Jewish people more broadly. “Long live Israel,” he declares in one poem, published in that same year; in another he marvels at how “a man condemned to be Shylock” has “returned to battle/ to the violent light of victory/ beautiful like a lion at noon.”

Written shortly after the Six-Day War—just when much of the literary world was beginning to turn against the Jewish state—these poems celebrating the Jews’ return to martial glory also stand in stark contrast to their cosmopolitan author’s own general suspicion of nationalism.

A half-century since the poems were written—and on the eve of Jerusalem Day, which this year falls on Sunday—its well worth revisiting the story behind them and the place of the Jews in Borges’s worldview.

Many scholars have proposed reasons for Borges’s philo-Semitism. The list of factors includes his Jewish friends in childhood; his Anglo-American grandmother who instilled in him a love for both the Bible and the people of the Bible; his admiration for Franz Kafka; and his fascination with Jewish mysticism, especially through the work of its great interpreter, Gershom Scholem. No doubt, all of these speculations are valid to some extent, but a closer look at Borges’s work shows something stronger at play. To understand what that is, it’s helpful to have some familiarity with his work more broadly.

Borges’s fiction, seen by many scholars and critics as the precursor to literary postmodernism, plays with perspective, with the boundaries that separate reader from writer, with the reliability of his frequently mysterious narrators, and indeed with the frequently uncertain meaning of his parables. In particular, Borges was fond of certain symbolic motifs, like libraries and labyrinths: mazes in which one can lose oneself in a dizzying multiplicity of ideas and historical periods. As the postmodern novelist David Foster Wallace noted in an oft-cited 2004 essay, Borges “knows that there’s finally no difference—that murderer and victim, detective and fugitive, performer and audience are the same.”

These cosmopolitan literary sensibilities spilled over into Borges’s politics. In his 1951 lecture “The Argentine Writer and Tradition,” he decried efforts to emphasize nationalism through literature: “What is our Argentine tradition?” he asked, “Our tradition is all of Western culture. . . . Our patrimony is the universe.” He was horrified by the more fascistic expressions of nationalism that he saw growing around him with the election of Juan Perón to the presidency of Argentina in 1946. By the same token, he publicly condemned Nazism and the Holocaust far earlier than most of his contemporaries, and took the Argentine intelligentsia to task for its pro-German and anti-Semitic leanings.

Yet one episode suggests that Borges’s political stance flowed not only from a hostility to chauvinism in general but also from a more specific philo-Semitism. In 1934, the Argentinian magazine Crisol attempted to discredit him by accusing him of having Jewish blood. He responded mockingly to Crisol in an essay “Yo, judio” (I, a Jew), in which he lamented his painstaking but ultimately futile effort to find some trace of Jewish lineage in his background:

Two-hundred years and I can’t find the Israelite; 200 years and my ancestor still eludes me. I am grateful for the stimulus provided by Crisol, but hope is dimming that I will ever be able to discover my link to the Table of the Breads and the Sea of Bronze; to Heine, Gleizer, and the ten Sefirot; to Ecclesiastes and Chaplin.

It may not have been especially noteworthy for a modernist author to admire such Jewish contributors to Western culture as Heinrich Heine (who converted to Christianity) or the Polish-born Brazilian actor and comedian Elias Gleizer, or even Charlie Chaplin—who, though not a Jew, could be seen as a stand-in for any number of Jews who distinguished themselves in Hollywood and in comedy, often taking Gentile-sounding names. Indeed, the choice of Heine and Chaplin suggests a liking especially for those Jews who have transcended, or even shed, their Jewish identities. Ecclesiastes, the one biblical book in this litany, bears little doctrinal or “national” stamp.

Not so, however, the reference to the “Table of the Breads and the Sea of Bronze”: items from Solomon’s Temple that conjure up elements of the Hebrew Bible most foreign to Christians—not to mention the ten s’firot (divine emanations) of Jewish mysticism. And as for Borges’s later extension of this admiration to the Jewish state, and his understanding of the role in Jewish history of its victory in the Six-Day War, these are nothing short of remarkable. When it came to Israel, his suspicion of nationalism seemed to disappear.

Consider the first of the three 1969 poems, “To Israel.” It utilizes one of Borges’s favorite symbols: the labyrinth, which customarily appears in his work as a site of infinite confusion or malevolent design. (Here and elsewhere I have used the translations of Ilan Stavans.)

Who shall tell if you, Israel, are to be found

In the lost labyrinth of secular rivers

That is my blood? Who shall locate the places

Where my blood and yours have navigated?

For the poem’s speaker, identity, and perhaps the world itself, constitute an inscrutable labyrinth, yet Israel appears as a guidepost of sorts. The deepest parts of his being are intertwined with the nation of Israel, and can’t ever be extricated. He continues:

It doesn’t matter. I know you’re in the Sacred

Book that comprehends Time, rescued in history

By the red Adam, as well as by the memory

And agony of the crucified One.

You’re in the book that is the mirror

Of each face approaching it,

As well as God’s face, which, in its complex

And hard crystal, is appreciated in terror.

Even if the poet isn’t quite sure where precisely Israel fits into this labyrinth, or into his own personal psychohistory, he holds that the Jewish people transcend time in a way that other nations do not. Even Christianity, he reminds us, testifies to the importance of Israel. Moreover, in a Borgesian landscape where subjectivity reigns, and everyone is prisoner to his own perspective, Israel remains present: “You’re in the book that is the mirror/ of each face approaching it.”

These sentiments lead to a triumphant conclusion most uncharacteristic of Borges: “Long live Israel, who keeps God’s wall/ In your passionate battle.” In contrast to his typically ironic voice and his use of an unreliable narrator, these final verses emerge as a personal credo in which appreciation of Jewish accomplishment in the Diaspora past spills over into exhilarated admiration for the Jewish present and post-Diaspora future.

Underscoring the point is an autobiographical essay published in the New Yorker in 1970. There Borges contrasted the vitality of the young state of Israel with what he saw in his own Argentinian homeland:

Early in 1969, invited by the Israeli government, I spent ten very exciting days in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. I brought home the conviction of having been in the oldest and the youngest of nations, of having come from a very living, vigilant land to a half-asleep nook of the world.

Indeed, one of his 1969 poems (“Israel, 1969”) explores just this paradox of the Jewish people’s simultaneous youth and antiquity, reflecting upon the “sweet insidiousness” that allowed Judaism to survive in various diasporas by resisting the swirling political currents around it, and that sprang into renewed life with the creation of the modern Jewish state:

What else were you, Israel, if not that nostalgia,

the will to safekeep,

from the inconstant shapes of time,

your old magical book, your liturgy,

your solitude with God?

But surely, the poet queries momentarily, the Jewish people’s perpetual outsider status and constant focus on the preservation of the past must have bred a certain national spiritual languor? To this he replies with a definitive “no”:

I was wrong. The oldest of nations

Is also the youngest.

You haven’t been tempted by gardens,

otherness and boredom,

but by the rigor of the last frontier.

A diaspora-based Judaism, however great a source of fascination and inspiration to the poet himself, must give way to a Judaism transformed on its native soil—and that is cause for celebration:

You shall forget your parents’ tongue

and learn the tongue of Paradise.

You shall be an Israeli. You shall be a soldier.

You shall build the homeland with swamps,

you shall erect it in deserts.

Your brother shall work with you,

he whose face you haven’t seen before.

Reading these poems, so wholly atypical of Borges’s oeuvre in general, one might be tempted to label them outliers. But writers have their soft spots, and in 1971 Borges freely stipulated as much in responding to the question of a Columbia University student about the role of politics in writing:

I think a writer’s duty is to be a writer, and if he can be a good writer, he is doing his duty. Besides, I think of my own opinions as being superficial. For example, I am a conservative; I hate the Communists; I hate the Nazis; I hate the anti-Semites, and so on. But I don’t allow these opinions to find their way into my writings—except, of course, when I was greatly elated about the Six-Day War. . . .

Even when Borges is at his most universalistic, there is that constant something pointing not just toward Israel but toward Judaism. In “The Aleph,” one of his best-known stories, a melancholy narrator stumbles upon the mythical single point at which everything in the world can be viewed and appreciated at once: “the only place on earth where all places are seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending.” The promise of the Aleph, even as it ultimately proves illusory, is that a single person can somehow gain access to, and connect with, the infinite complexity of mankind and the universe.

In “The Aleph,” Borges draws on several Jewish and specifically kabbalistic symbols: Ezekiel’s description of the divine chariot (one of the biblical touchstones of classical kabbalah); the kabbalistic term “Eyn Sof,” the Limitless One, which refers to God’s unknowable and undefinable ultimate essence; and of course the use of the Hebrew alphabet itself, which he terms “the sacred language.”

True, he intersperses these references with others to Persian mysticism, esoteric mathematical theories, 1001 Nights, the ancient Roman Satyricon, the Faerie Queene, Hamlet, Hobbes’s Leviathan, and numerous other texts and traditions. It’s thus all too easy to understand him as viewing these diverse sources of wisdom as interchangeable, or at least as sharing a common source. Yet the role he assigns to the Hebrew language is unique, since it is only by finding the Aleph that a person can see all else clearly.

There are certainly many elements of Borges’s writing that suit today’s fashionable multiculturalism, universalism, and the idea that identity is purely subjective and self-created. His characters’ identities do often seem arbitrary, as are the various cultures and national traditions he draws upon. Yet Borges disorients us not in order to pursue a kind of epistemological chaos but in order to get somewhere deeper.

Even the most complex labyrinth has a center. As Borges seems to understand that center, it is located in the conceptual space of Judaism and perhaps even in the physical space occupied by the modern Jewish state. In his postmodern, relativistic, and labyrinthine universe, where identities are interchangeable, truth is subjective, and final evaluations are impossible, these provide the one true north by which all moral compasses can be set.