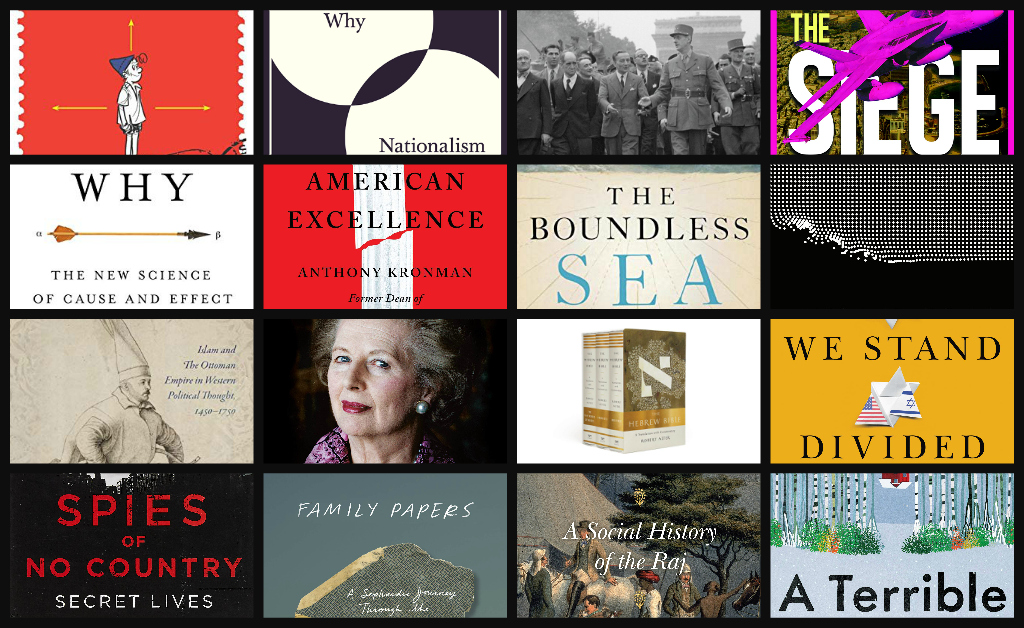

To mark the close of 2019, we asked several of our writers to name the best two or three books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. The first seven of their answers appear below in alphabetical order. The rest will appear tomorrow. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2019.)

Elliott Abrams

Julian Jackson, De Gaulle (Belknap Press, 2018, 928pp., $39.85). This lengthy biography by the best British historian of 20th-century France is generally sympathetic—though the perspective is inescapably that of a foreign observer, and less taken with French grandeur than a native might well be. Beautifully written and comprehensive, it includes very interesting discussions of De Gaulle’s attitude toward French Jews in decades when the French army and French right were deeply anti-Semitic, and toward Israel when he was France’s president.

Shmuel Rosner and Camil Fuchs, #IsraeliJudaism: Portrait of a Cultural Revolution (Jewish People Policy Institute, 282pp., $19.99) has now come out in English. The authors use survey data and some wonderful stories to describe the changes that are occurring to the religion as it is actually practiced in the first Jewish state in 2,000 years. It’s a fascinating portrait. (Read Mosaic’s review here—Ed.)

Diana Muir Appelbaum

Yael Tamir, Why Nationalism (Princeton, 224pp., $24.95). Tamir makes a persuasive case for nationalism’s ability to produce and sustain liberal democratic government by arguing that the ongoing sense of nationhood shared by the people of countries like Japan, Denmark, and Israel over the course of generations and centuries enables them to trust one another enough to disagree politically—and even to lose elections—without falling prey to dictatorship, oligarchy, or civil war. An important contribution to the study of nationhood and of democracy, written in language accessible to general readers.

Hesh Kestin, The Siege of Tel Aviv (Dzanc Books, 304pp., $33.76). A political thriller blurbed by the novelist Stephen King, who described it as “scarier than anything Stephen King ever wrote.” It was withdrawn by Kestin’s longtime publisher after an anti-Israel Twitterstorm. The publisher explained that “it was never our intent to publish a novel that shows Muslims in a bad light” and offered to donate profits from early sales to “a Muslim relief organization.” The book has been republished and is available from Amazon. The plot involves the armies of several Arab states, led by Iran, making a Yom Kippur War-style surprise attack on Israel. The invaders overwhelm the IDF, forcing six million Jews into “Ghetto Tel Aviv.” The invaders cut off food, water, and electricity and the world waits for the Jews to die. Then the Israelis fight back. And win. An exciting read.

Matti Friedman, Spies of No Country; Secret Lives at the Birth of Israel (Algonquin Books, 272pp., $26.95). A fascinating exploration of the complex identities of the Arabic-speaking Palmaḥniks, natives of Arab lands who undertook aliyah to the yishuv and who were then sent to live as Muslims in the cities of the invading Arab countries and spy for a Jewish state that was fighting to be born. Friedman not only shows us the near-impossibility of successfully pretending to be someone who you are not, and the heartrending loneliness of the spy, but also reframes the conflict. Although propagandists portray Israel as a European imperialist project, Friedman writes that Israel is more accurately described as a country reborn as “a refugee camp for the Jews of Europe” and “a minority insurrection inside the world of Islam.” It’s a great read. (Read Mosaic’s review here—Ed.)

Matti Friedman

Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey Through the Twentieth Century (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 336pp., $28). This is a touching microhistory about one Jewish family from Salonica, the Levys, and how a few generations experienced the upheaval of the 20th century: the end of the Ottoman empire, the rise of nationalism, emigration to other countries and continents, the Nazi genocide in Greece, and betrayal by one of their own. Salonica (now Thessaloniki) had a Ladino-speaking Jewish majority in Ottoman times, and even its port rested on Shabbat; David Ben-Gurion, who spent time there as a young man, described it as “the most Jewish city in the world.” Family Papers brings it to life and teaches us something about human ties and modern times.

David Gilmour, The British in India: A Social History of the Raj (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018, 640pp., $35). The most enjoyable history book I’ve read recently: a colorful, trenchant, and sympathetic portrait of British colonialists in India over several centuries. In its description of army barracks, aristocratic parties at Simla, and complicated love lives, Gilmour’s book sheds indirect light on the imperialists who—in what turned out to be one of their last dramatic flourishes—helped bring about a Jewish homeland in the land of Israel before vanishing into the more democratic and less interesting version of Britain that emerged after World War II.

Keith Gessen, A Terrible Country: A Novel (Penguin, 352pp., $15.99). A comic novel about the return of a young Russian-Jewish-American to Moscow after his academic and romantic aspirations are thwarted in the U.S. While caring for his ailing grandmother, who stayed behind when everyone else left, he explores the 21st-century landscape of the Russian capital and finds brute capitalism, pick-up hockey, a few avid idealists, and little hope. A serious story executed with an admirably light touch.

Haviv Rettig Gur

“Zionism” is a remarkably flexible little word whose supporters and detractors are divided not so much in their assessment of the movement’s moral validity as in their sense of what the word itself actually refers to. Those who imagine in their mind’s eye an organizing framework through which Jews rescued themselves from the atrocities and vulnerabilities that are the fate of so many modern-day minorities will tend to view it favorably. Those who ignore the historical experience of millions of real people and instead focus on a narrow fin-de-siècle European intellectual movement—or, more often, on a cartoonishly polemical shrinking of that movement to fit the needs of present-day moral judgment—will tend to view it unfavorably.

Perhaps the most interesting observers of Zionism, however, are those torn between these two semantic imaginings: the leftist intellectuals too devoted to their universalism to countenance anyone selling a vision of salvation through nationalism, but nevertheless too intellectually honest to pretend they have a better solution for the Jews ultimately rescued by, ahem, Zionism. Susie Linfield’s new book The Lion’s Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky (Yale, 400pp., $32.50) is a deep and well-written dive into the intellectual worlds of eight such leftist thinkers who wrestled in different ways, and to varying degrees of intellectual honesty and success, with the many layers of Zionism. It is an eye-opening and rewarding journey profoundly relevant to today’s debates on the left about something the left is also calling “Zionism.” (Read Mosaic’s review here.)

Then again, if your preference leans more toward examining Israel and Israelis on their own terms, this year saw what feels like the start of a startlingly fresh and self-critical new discussion among Israelis about the character and future of Israeli society. The most important starting point for this discussion may be #IsraeliJudaism: Portrait of a Cultural Revolution by Shmuel Rosner and Camil Fuchs (Jewish People Policy Institute, 282pp., $19.99), which thankfully eschews arcane academic verbiage or ideological polemic for the blunter and ultimately more revealing instrument of actually asking Israelis about their identity. The results are vital reading for anyone interested in understanding both the character of the Israeli Jewish polity and the future of the broader Jewish people.

Another book, Daniel Gordis’s We Stand Divided: The Rift Between American Jews and Israel (Ecco, 304pp., $26.99), takes a distinctively Israeli view of the ways Israelis misunderstand their American Jewish counterparts, and vice- versa. Part polemic, part sweeping analysis, part accusation over the weaknesses of American Jewish life, the book is ultimately a call for American Jews both to fix and to be fixed by their increasingly distant cousins in the Holy Land. It’s a nuanced but simultaneously visceral and heartfelt take on what has become a despairingly stilted and shallow conversation about the “gap” between Israeli and American Jews.

Daniel Johnson

The literary crop of 2019 has been a bumper one, which makes the choice of just two books especially hard. But before I get to them: accompanying me through the year have been the three great volumes of Robert Alter’s translation of and commentary on The Hebrew Bible (Norton, 3,500pp., $125): not so much a book as the Book. [Read Mosaic’s review of Alter’s Bible translation, and responses thereto, here—Ed.] Also, just out is David Abulafia’s The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans (Oxford, 1,088pp., $39.95), as prodigious as the vast deep it chronicles.

This literary abundance gives the lie to gloomsters who prophesy the end of the book. Hence I have chosen two books that are perhaps more challenging than most, though not for the learned readers of Mosaic.

Who reads three-volume biographies anymore? Who, indeed, deserves such monumental treatment? Margaret Thatcher, that’s who. Charles Moore’s life of Britain’s greatest postwar prime minister has reached its climax with his gripping account of her third and final term, her downfall, and the aftermath. What makes Herself Alone, volume three of Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography (Knopf, 1,056 pp., $40), such a triumph of the biographer’s art is the author’s ability to condense colossal quantities of material—almost all of it new—into a grand narrative that never loses momentum. Mrs. Thatcher’s statesmanship emerges throughout the book, even when high drama descends to low skullduggery as her ungrateful party turns on her and ruthlessly casts her out of office.

The “lioness in winter,” as Moore calls her, had been impaled on the issue of Europe, and she used her time in exile to prepare the ground for what would, a quarter of a century later, become known as “Brexit.” Not only was she instrumental in promoting the idea of a referendum, but already in 1992 she envisaged Britain becoming “a kind of free-trade and non-interventionist Singapore off Europe.” Her revenge was posthumous but none the less effective for that.

Moore concludes on a more elegiac note:

What Mrs. Thatcher loved in her country—its liberty, its lawfulness, its enterprise, its readiness to fight, its civilizing, English-speaking mission—was not always visible in the place that she actually governed, nor was her love always requited. But great loves such as hers go beyond reason, which is why they stir others, as leaders must if they are to achieve anything out of the ordinary.

Looking back at her career, it is a source of sadness for me that her love and admiration for the Jewish people and for Israel should have become so rare among European leaders.

My second book of the year is Noel Malcolm’s Useful Enemies: Islam and The Ottoman Empire in Western Political Thought, 1450-1750 (Oxford, 512pp., $34.95). The author is one of the great scholars of our time, even more of a polymath and polyglot than the late and much-lamented Bernard Lewis. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the impact of Islam and the threat of a Turkish invasion held up a mirror to Christendom. Malcolm’s title, Useful Enemies, reflects the uses and abuses of this East-West encounter, which enabled Europeans to question their own civilization by comparing and contrasting it with the Ottoman-dominated Orient.

Malcolm has here uncovered an entirely new field of inquiry, ranging from Machiavelli to Montesquieu, and embracing many less familiar but fascinating thinkers en route. It is of course no accident that such a groundbreaking work should have been written in our time. Not only are there parallels to be drawn between the early-modern encounter with Islam and our own, but some of the concepts—from reason of state to despotism—that still underlie politics today took shape in this older clash of civilizations.

Five years ago, Malcolm was knighted for services not only to scholarship but also to journalism and European history. Here he allows himself to venture into present-day controversy only once—but with deadly effect. In three luminous pages, he destroys the claims of Edward Said’s Orientalism to be taken seriously. What he shows is “active—even creative—engagement [by Western Orientalists] with their Islamic or Ottoman subject matter as part of a larger pursuit of religious and political arguments within their own culture. The Eastern material was not there to be beaten down, as Said imagined, into conformity with complacent Western attitudes,” Malcolm writes. “Often it was used to shake things up, to provoke, to shame, to galvanize.” That is exactly what Malcom has done with Useful Enemies—not, like Said, to close minds, but to open them.

Moshe Koppel

Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie, The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect (Basic, 2018, 432pp., $32). Pearl, one of the founders of artificial intelligence, and Mackenzie use formal models to solve one of the thorniest problems in the philosophy of science: distinguishing between causality and mere correlation. The book is deep but accessible, and adds a necessary dimension to the burgeoning field of data science. (Pearl, by the way, was born in Tel Aviv and is a deeply committed Jew. He is also the father of Daniel Pearl, the journalist murdered by al-Qaeda in 2002.)

Ben Shapiro, The Right Side of History: How Reason and Moral Purpose Made the West Great (Broadside, 288pp., $27.99). Shapiro argues that revelation and rational inquiry, religion and science, rooted in Jewish and Greek thought, respectively, jointly constitute the foundation for the freedom and prosperity we enjoy today and that progressives neglect them at our collective peril. The arguments are characteristically combative, but serious.

Daniel Polisar

I am interested primarily in non-fiction, and 2019 was a particularly rich year for superb books—making it particularly hard to narrow the list down to three.

Bari Weiss’s How to Fight Anti-Semitism (Crown, 224pp., $20) is an excellent introduction to a topic that unfortunately is becoming increasingly and ominously relevant. The author has succeeded in an extraordinary balancing act, writing a work that is at once a powerful polemic and a fair-minded treatment of a complex subject—and that is a gripping read for a broad audience while simultaneously meeting the demands of readers who insist on rigorous standards of proof.

Anthony Kronman, in The Assault on American Excellence (Free Press, 288pp., $27), has produced a worthy successor to his justly admired Education’s End. His latest work makes a compelling case that colleges and universities in the U.S. have given up on their true hallmark, the quest to inspire intellectual and ethical greatness, due to a mistaken belief that all elements of the contemporary democratic ethos must be applied in every area of academia. He challenges the beliefs of the vast majority of people involved in higher education—administrators, faculty, students, and parents alike—and it is to be hoped that those inclined to disagree with him most strongly will be able to bring themselves to read his book with an open mind.

David Epstein’s Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World (Riverhead, 352pp., $28) is a paradigm-shifting book with the potential to change the way we see a host of areas. The author makes the case, based on substantial evidence from a broad set of fields, that the path to success and fulfillment is early exposure to a range of activities and disciplines, followed later by specialization, rather than a consistent and single-minded focus on a particular area of expertise. His work has implications for parenting, education, career development, and most importantly, for the way that thoughtful people should lead their lives.

Tune in again tomorrow for Part II of our Best Books of 2019.

More about: Arts & Culture, Best Books of the Year, History & Ideas, Literature, Politics & Current Affairs