Cheers, bravos, and five curtain calls greeted the shattering finale to Mieczysław Weinberg’s Piano Trio in A minor: a work written in Moscow in 1945 and performed in late October of this year at London’s Wigmore Hall as the climax of an entire day devoted to Weinberg’s chamber music. The great Polish-Soviet Jewish composer was born 100 years ago, on December 8, 1919, and his centenary year has seen numerous performances by important artists in major venues as well as conferences and books devoted to his work.

Still, until now, very few have heard of him. This has been a source of frustration to those who have worked closely with his music, or who are familiar with his harrowing, Holocaust-themed opera The Passenger, his delightful Sixth String Quartet, or his 21st symphony (“Kaddish”)—as powerful a musical commemoration of the victims of 20th-century tyranny as is to be found anywhere.

Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, chief conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, had this to say about her experience of performing and recording the Kaddish Symphony, which she calls “a sonic monument for the tragedy of the 20th century”:

It’s an epic. . . . The second movement is maybe one of the most beautiful adagios I know. I’m burning to do more. As I get to know Weinberg better, each new piece is greater than the last. I think he will be an exploration for a whole lifetime.

Her recording of this work features the world-renowned violinist Gidon Kremer, whose excited reaction to the Kaddish Symphony echoes hers:

It was actually as if one had discovered Mahler’s [non-existent] Eleventh Symphony. A musical monument that sets to music one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century.

Why Weinberg’s name is still relatively obscure—certainly as compared with that of his great friend and contemporary Dmitri Shostakovich—is explored in a recently published book about him by Daniel Elphick. The reason, Elphick ventures, can in part be found in controversies over “questions of heritage and identity.” “Academic conferences have broken down into arguments of cultural ownership,” writes Elphick, “with the crude determiner ‘our’ used on multiple occasions to make the claim that Weinberg’s music might ‘belong’ to any one particular group or nation.”

But however beguiled academics might be by the issue of whether Weinberg and his music are to be regarded as Polish, Russian, or Jewish (or all three), the question is wholly irrelevant to an appreciation of the indisputably high quality of his music, or of the man who wrote it.

Weinberg’s work first crossed my own musical horizon after I’d been performing Yiddish songs in Washington for Pro Musica Hebraica, an organization devoted to retrieving important but neglected Jewish classical music. Robyn Krauthammer, the organization’s chief executive, sent me a private recording of an ARC Ensemble concert. I listened to it blind. All of the pieces were of interest, but one was right up there with the greatest chamber music of the 20th century—by, for instance, the likes of Shostakovich, Arnold Schoenberg, or Béla Bartók. It was the extended final movement of Weinberg’s piano quintet: harmonically complex and demanding to play but passionate, utterly sincere, immediately memorable.

Encouraged by Pro Musica Hebraica to put together a song program focusing on mid-20th-century Jewish composers, I found once again that the music of one, Mieczysław Weinberg, stood out. Given the size of his output, which includes over 200 solo songs, it became entirely feasible to devote an entire program just to him.

Weinberg’s life story is a biography of 20th-century Central Europe itself, in all of its tragedy and horror. His grandfather and great-grandfather had been among the 49 Jews killed in the 1903 Kishinev pogrom, and his father might well have suffered the same fate had he not left for Warsaw several years earlier.

Both of his parents were musicians, his mother Sura Stern a singer and his father Shmuel a violinist who had begun playing at the age of seven, eventually attaching himself to a touring group of which he became both conductor and chorus master. In 1916, Shmuel joined the Warsaw Jewish Theater; in recordings from 1929-30 on the Syrena label, one can hear performances of him conducting liturgical pieces with the cantor Jacob Koussevitsky and Yiddish melodies with the singer Giza Heiden.

The young Mieczysław, “Metek” to friends and family, began his own musical education playing the violin alongside his father at the Warsaw Jewish Theatre and at Jewish weddings. “When I was six I followed him,” the son would later recall, “and went to listen to all these low-quality but very heartfelt melodies. . . . [Later] I took gigs at Jewish weddings where I would play folklore songs, mazal tovs, [and] accompany the cantors. . . . Then at night I would play in a cafe: foxtrots, waltzes, slow dances.”

A native Polish speaker, Mieczysław lacked Hebrew but understood (even if he could not speak) Yiddish. When the Germans invaded in September 1939, he fled to Minsk in Soviet Belorussia with his younger sister Esther, only for Esther to turn back complaining that the shoes hurt her feet. She would be interned with her parents in the Łódź ghetto and eventually murdered with them in the Trawniki concentration camp.

With the Nazi invasion of Belorussia in 1941, Weinberg was forced to flee again, this time a distance of 3,000 miles to Tashkent, where many of Russia’s intellectual and artistic community had been evacuated. There he met his first wife, Nataliya, daughter of the great Russian Jewish actor Solomon Mikhoels.

An early song cycle, Acacias, composed in Minsk in 1940, reveals a twenty-year-old composer still under the influence of Impressionism. But he was also becoming familiar with the modernist music of Shostakovich, which he had first encountered a year earlier at a performance in Minsk of the composer’s Fifth Symphony. “I was staggered by every phrase, every musical idea,” he would later remember, “as if a thousand electrical charges were piercing me.”

Shostakovich would have an enormous impact on Weinberg’s development, and not only musically. Impressed by the score of Weinberg’s First Symphony, possibly sent to him by Mikhoels, the Russian master invited the young man to come and reside in Moscow. There, living in close propinquity as neighbors, the two became close friends and colleagues, and would regularly play through one another’s scores sitting four-hand at the piano. (An electrifying recording survives of the two playing Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony.) Weinberg’s name appears more frequently than any other in the Russian composer’s diary.

Following his move to Moscow, Weinberg’s forward progress can be measured by his 1943 settings of I.L. Peretz’s Yiddish children’s verse. In these superficially simple songs, some of his musical and compositional hallmarks are already starting to become apparent: the darkness always lurking beneath the surface of even the most apparently light-hearted melodies, the constant search for something new to say musically, the through-written nature of the compositions themselves. Already in these songs, Weinberg’s music mows relentlessly past conventional bar-lines; key signatures, similarly, are taken as fluid rather than fixed, and deviations from them (“accidentals”) are abundant.

Nor does Weinberg display any particular reverence for the instruments he writes for, human or otherwise. Singers are stretched to the extremes of their range, pianists require a hand span like the one notoriously demanded by the composer Sergei Rachmaninov. In short, Weinberg has something to say, and the performer’s task is to find the means of expressing it. As, decades later, he would write rather portentously to his wife:

A composer is someone who can illuminate with his own light—not like anyone else’s—what lies within each of us.

“Traditionalism,” “avant-gardism,” “modernism” have no meaning. Only one thing is important: that which is yours alone. . . . But to be a composer isn’t a pastime, it’s an eternal conversation, an eternal search for harmony in people and nature. It’s a search for the meaning and duty of our short-lived existence on the earth.

It may be in keeping with this grand pronouncement that the “search for meaning and duty” in Weinberg’s music is often so idiosyncratic and ambiguous, to the point where his own actual attitude can be difficult to place or define. Thus, an ode to Stalin, written in 1947, one of his Opus 38 settings of Soviet poetry, appears to be a four-square celebration of the dictator’s achievements. But is that because the circumstances surrounding its composition—the Soviet Union’s recent triumph over the Nazis—were such that the composer himself, despite his own bitter experience of Stalinist autocracy, might have been carried away by the poem’s euphoria? Or is the atonal coda at the end of each verse a subtle compositional subversion of an otherwise triumphal paean?

A year after the writing of these songs, Weinberg’s famous father-in-law Mikhoels was murdered on Stalin’s orders, possibly because of his participation in a group documenting Soviet collaboration in the Nazi Holocaust. Tarred by association, and accused of “Jewish bourgeois nationalism,” Weinberg himself became something of a pariah.

Prikaz 17, a diktat circulated to every musical institute in the USSR, listed all of the musical works banned by the regime. Among them was Weinberg’s great Sixth String Quartet (1946). Like so many of his finest works, it would not be performed until decades later—even though, as Elphick writes, its excellence was already great enough to reveal “the comparative lack of quality in Shostakovich’s early essays in the [same] genre.”

Eleven years would pass before Weinberg wrote another string quartet. In total he composed seventeen, a cycle that ranks as one of the most important of its kind in the 20th century.

By February 1953, on one pretext or another, he was thrown into jail, confined to a cell so small he was unable to lie down. Shostakovich interceded on his behalf with Lavrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD, but to no avail. Had Stalin not died two months later, it is highly likely he would have been sent to the gulag.

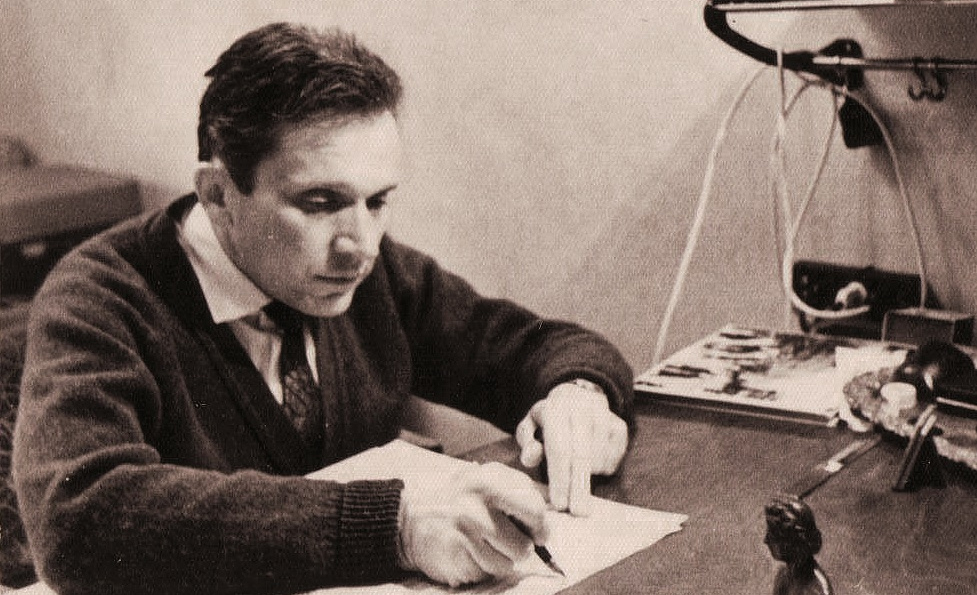

In his 1956 song cycle The Gypsy Bible, dedicated to Shostakovich, Weinberg continued a lifelong creative relationship with an idealized version of his native Poland, embodied for him in the work of the great Polish-Jewish poet Julian Tuwim. A photo shows Weinberg at work, a complete edition of Tuwim’s poetry on his desk, a photograph of his friend and mentor Shostakovich on the adjacent wall.

Throughout this song cycle, Weinberg’s music is infused with Jewish folk idioms. In one of them, his setting of the harrowing poem Żydek (“Little Jew”)—written by Tuwim in 1933, the poem is a direct take on the parlous state of pre-war Central European Jewry—Weinberg quotes Shostakovich’s musical signature (the notes D, E-flat, C, B, yielding the letters “DSCH”) in accompaniment to the phrase “lost in the huge, foreign, inimical world.”

In 1966, Weinberg was invited back to Poland for the Warsaw music festival as one in a delegation of Soviet composers. It was his first visit to the country since fleeing in 1939. The experience was not a good one. If it were not shattering enough to behold the city of his childhood almost completely destroyed (though, miraculously, his family home survived) and finally to confirm the fate of his parents and sister, he found himself ostracized by his Polish musical contemporaries.

Thereafter Weinberg would distance himself from Poland and its culture. Only in his Ninth Symphony, in the opera The Passenger, and in the song Memorial, dedicated to his mother, did he set any texts by Polish authors. Memorial also contains a reference to one of his earliest works, Mazurka, which he also drew on for his Sixteenth Quartet dedicated to his sister, Esther, who would have been sixty in the year of composition. As Elphick notes:

The thematic material of this quartet, especially in the fourth movement, represents some of Weinberg’s strongest re-engagement with Jewish music in his later period. Weinberg had suffered with the loss of his family throughout his life; it seems to have become far more intensely felt during his final decades.

From the 1970s on, the eventfulness of Weinberg’s life diminished in direct proportion to the increase in his musical output, which would grow to include six operas and a huge symphonic cycle. Shostakovich’s death in 1975 was a double blow: the loss both of a close personal friend and of his most important musical mentor.

A year later, in his Opus 116 cycle of settings of the 19th-century Russian poet Vasily Zhukovsky, he tackled songs relating to loss and transience, some of them quite exquisite while also marking a return to the Impressionist tonality of his earliest work: sparse piano accompaniments interwoven with the vocal line to evoke colors appropriate to the pervasive melancholy of the themes.

In the late 1980s, Weinberg was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. Tommy Persson, a Swedish aficionado of his music, procured for him medicine unavailable in Russia. “I have to complain to you about the Creator,” Weinberg joked on one occasion. “As you can see, His idea of old age was not a success.” In the winter of 1995, he discussed with his second wife, Olga Rakhalsky, the possibility of converting to Orthodox Christianity, and in February 1996, a few weeks before his death, was baptized into that faith.

As a Jew, Weinberg had always been religiously non-observant, but he was culturally Jewish enough to agree to being designated as Jewish rather than Polish upon entering the Soviet Union. As for the decision to convert, his daughter Anna (by his second marriage) claims it was “made entirely in his right mind.” That claim would be disputed by Victoria, his first daughter by Nataliya Vovsi-Mikhoels, who in support cited a statement by Anna that in his last months Weinberg had “lost his mind, suffered very much, and did not understand what was happening around him.” In that case, concluded Victoria, “What kind of voluntary baptism can we talk about?”

For her own part, Weinberg’s second wife Olga insisted that he had “considered the decision to be baptized for about a year” and “at the end of November [1995] . . . asked that a priest baptize him. A month later, . . . Weinberg was baptized in his right mind and died in full consciousness.”

He was buried next to his mother-in-law in the Russian Orthodox cemetery at Domodedovo, close to the Moscow airport.

To lovers of his music, it is tempting to interpret Weinberg’s conversion as a last laugh, a final, protean twist intended to confound those who tried (and still try) to define him through prisms of religion and nationality.

Indeed, Soviet critics had praised his music particularly for its Jewishness—paradoxically, the same Jewishness that would subsequently lead to the music’s being proscribed and “imprisoned.” And, whether consciously or subconsciously, that music certainly brims with Jewish motifs, with the Holocaust being one constant refrain.

Like so much else, Weinberg’s settings of the Yiddish verse of Shmuel Halkin (1897-1960) remained unpublished during his lifetime. Halkin’s Tifeh griber, royteh leym (“Deep Pits, Red Clay”), written in 1943 in full awareness of the Nazi horror and, not least, the destruction of his own family, is believed to be the poet’s response to the terrible September 1941 massacre at Babi Yar outside Kiev, where 34,000 Jews were murdered.

Halkin’s poem ends, or almost ends, with an ambiguous vision of children one day playing above the now overgrown death-pits. Weinberg was later to make his setting of the poem into the theme of the last movement of his Sixth Symphony, in which it is sung by a children’s chorus. Arguably the most powerful classical Holocaust song ever penned, it achieves its effect through a typically Weinbergian restraint, beneath which simmers the horror of the events being described. He allows the musicians full rein only at the very end, after the vision of the playing children, in the closing line, az der vay zol nit ariber.

But what does the line mean? “Lest the agony prevail”? Or “Lest the agony pass away”? The stark ambiguity, enabled by the nuances of the Yiddish adverb ariber, haunts the music as well.

Weinberg’s finest song cycle may be his 1960 settings of Russian translations of Sándor Petőfi, the 19th-century Hungarian revolutionary and national poet. Yesli by (“Only if”), in which the poet describes God allowing the speaker to choose the method of his death, ends with a celebration of Svaboda (freedom)—the same word that concludes Weinberg’s 1947 ode to Stalin—but whereas in the earlier usage Weinberg was apparently only paying lip-service to the dictator, here the music rings true to the words. “Freedom, Freedom, you are the supreme heavenly being” becomes an impassioned cry, finishing on a sustained top note in which the idea of creative freedom must have become, as in the song, more cherished by Weinberg than love itself.

The same song makes an appearance in The Passenger, his greatest opera, an evocation of Auschwitz based on a novel of the same title by the Polish author Zofia Posmysz. Sung by the heroine Marta, the song becomes the work’s central aria.

The Passenger was composed by Weinberg in 1968 but not given its first performance (in Moscow) until 2006, ten years after his death, and not fully staged until 2010. How galling the long wait must have been for Weinberg, who named the opera as his most important work, adding, “All my other works are The Passenger also.” Shostakovich considered it a masterpiece, but after having been scheduled for performance at the Bolshoi it was quietly dropped and theater managers were advised not to stage it.

No doubt the dominant factor in its silencing was the Soviet attitude toward Holocaust commemoration. What had happened on Russian soil was to be treated as a national disaster, not just one affecting the Jewish population—and certainly not one in which even the slightest hint of Soviet complicity could be tolerated.

Ironically enough, Weinberg and his librettist Alexander Medvedev, taking their cue from the novel (and perhaps hoping they could thereby avoid provoking the Soviet censors), had not actually focused on the Jewish experience of Auschwitz. Instead, they set the opera in the women’s camp, where Posmysz herself had been held, and featured mainly Polish, Russian, and Greek characters. Only the French inmate was given an explicitly Jewish identity.

Imprisoned by the Soviets for its allegedly Jewish theme, in America, to compound the irony, The Passenger would be criticized as too “international.” Reviewing its performance at New York’s Lincoln Center in 2014, a writer in Tablet called it “an opera set in the killing factory known for subtracting Jews from the world, and it subtracts Jews.” Readers commenting on the review concurred, with one opining that “many Holocaust deniers in the world will use this as proof that Jews were not special victims of Nazi Germany,” and another asserting that “removing or minimizing the uniquely Jewish experience of the Holocaust is just one form of Holocaust denial.”

Taking the irony still farther, the general director of the Israeli Opera, in a speech delivered before this year’s Tel Aviv premiere of The Passenger, re-universalized its message by claiming its heroine Marta as, in effect, an Anne Frank for our day. The “message we need to bring to humanity,” he intoned, is about the danger of nationalism and populism, “which have once again been rearing their heads.”

To Daniel Elphick in his book about Weinberg, the composer’s “blend of identities and their overarching humanist message,” and not just in The Passenger, “is ultimately what makes [his] music so powerful.” Weinberg’s music, he writes, “tells us something very complex, honest, optimistic and fatalistic, about what it means to be human, and the loves and losses that occur as a result.”

Be that as it may, I return to what I said early on: what will ultimately guarantee Weinberg’s place in the pantheon of great 20th-century composers is the sheer musical genius of so much of his vast oeuvre. Rather than categorizing him in terms of nationality, religion, politics, or credo, we do better to let his music engage and stir us with its mastery, its force, its beauty, and its depths of emotional power. All other questions are secondary.

More about: Arts & Culture, Classical music, Holocaust, Mieczysław Weinberg, Music