Commonly held attitudes about the overall health of society can be seen in the things we worry about.

Take, for example, a realization that seems recently to have come to numbers of people who share a given professional field or discipline. How widespread is the realization? That remains impossible to say, but whether you are a schoolteacher or a lawyer, or perhaps a scholar of the humanities, you begin to worry that your field has ceased to advance. There are fewer creative breakthroughs, everyone seems to be going through the motions, and the entire endeavor slopes toward listlessness.

You share this sense of things with colleagues, and you also share a bit of comfort in agreeing that there is a saving grace to be found in other spheres of endeavor than your own. Surely, you suggest, technology and the hard sciences are whirring ahead.

But then you find out that we are all languishing together, and that in disciplines from mathematics to the sciences, the fears born of your own expert experience are replicated everywhere else. Even the string theorists don’t seem to provide the hope that—just a few years back—you thought they might.

What is one to call this condition? Perhaps “The Great Enervation”? For Ross Douthat, in a possibly prescient book, it has become the underlying attribute of well-off liberal democracies like America and Europe: what he has here chosen to describe as The Decadent Society.

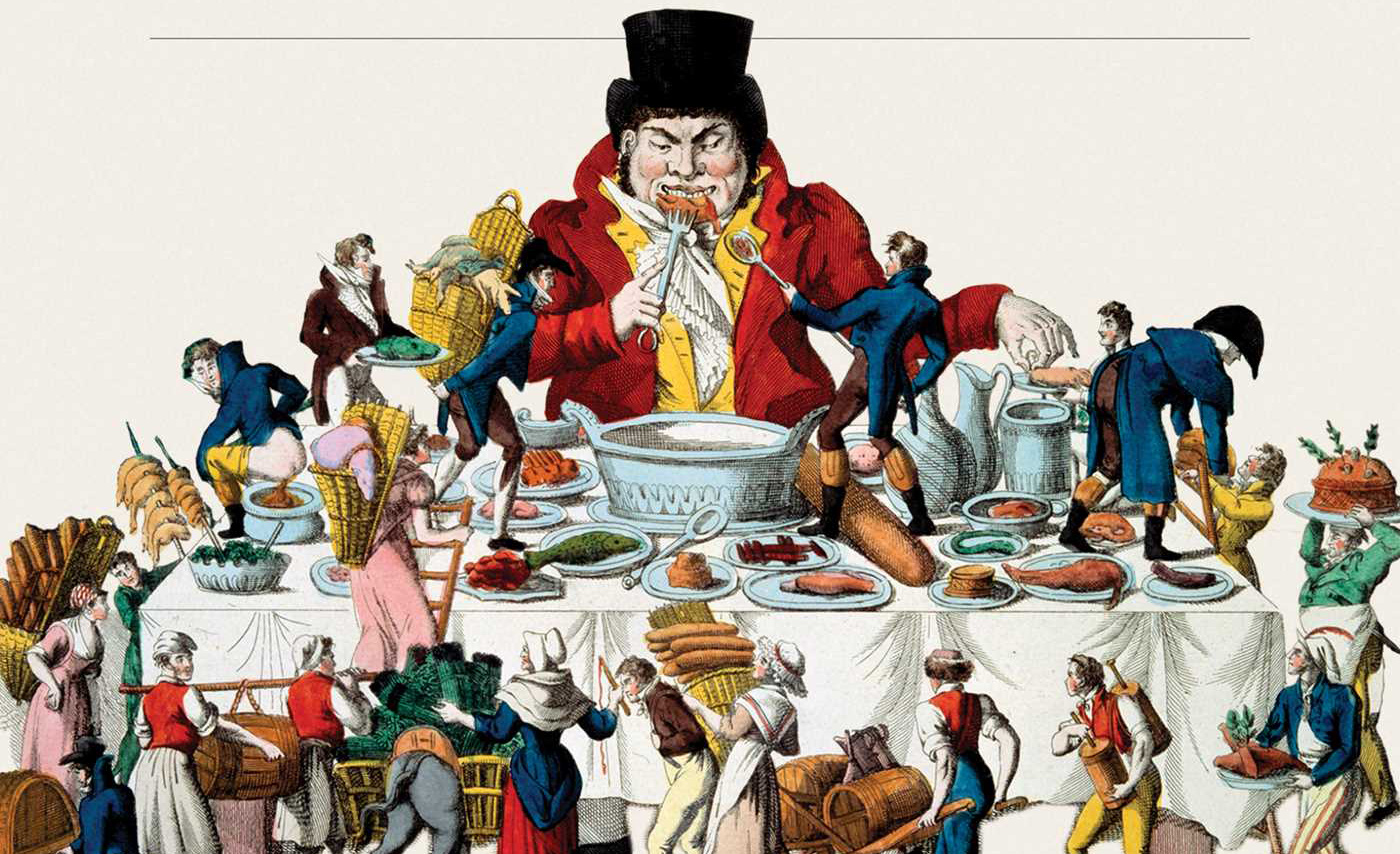

Douthat starts by conceding the difficulty of terms. Even more than most words, “decadence” slips and slides around, used promiscuously, often in moral judgment but also to signal allegedly immoral attractiveness (as in “This chocolate cake is so decadent”). But following the lead of the cultural historian Jacques Barzun in such examples as fin de siècle Paris and Weimar Germany, decadence for Douthat has come to suggest a sense of winding down toward a point not yet fully determined: a “falling off” that “need not mean stoppage or total ruin,” or the inevitable prelude to the deluge.

We’ll return to this later. In the meantime, Douthat is firm in stating his aim: “to convince you that our society is, indeed, decadent; that my definition actually applies to the contemporary West over the last two generations and may apply soon to all the societies that are currently catching up to Europe and North America and East Asia.”

Douthat identifies four key markers of a decadent society: “the four horsemen,” as he perhaps too predictably calls them. They are stagnation; sterility; sclerosis; and repetition. Let’s look at each in turn.

The stagnation of the West can be seen in the fact that, pretty much since the moon landing, more than 50 years ago, there have been no major leaps forward in our understanding of ourselves or of the universe. In fact, technological advances that promised to draw us out of our selves have instead led us inward. From the heights of space-age optimism, one would have never predicted the destination to which our technological genius has led us, as we walk down the street and across the fields staring into a small screen. In our enslavement to these small screens, the freedom we still exercise comes to seem wholly imaginary.

For evidence of sterility, Douthat looks to the demographics of the West, whose inhabitants are unwilling or unable to reproduce. Despite this fact, our societies refuse even to recognize that this is a problem worth addressing. Worse, the culture supplies incentives for us to carry on in our slouch toward decline. So we have what Douthat terms the “kindly despotism” in which Silicon Valley workers are offered workout centers and “polished yoga spaces but no child-care options.”

To keep their societies young, European democracies turned to an open-borders immigration policy. They may have thought they were acting out of a cosmopolitan and universal love for their fellow humans; as Douthat analyzes it, the deliberate importing of immigrants from traditional societies has functioned rather as compensation for the fact that we are no longer giving birth to or raising a new generation ourselves.

Of course, there is the extraordinary case of Israel, a nation that shares much with the civilizational background of Europe and America but that nevertheless continues to produce children at numbers exceeding the rate of replacement. Douthat acknowledges this fact, but perhaps misses here an opportunity to further analyze what Europeans and Americans can learn from its example of national health.

Sclerosis, the third source of decadence, is on display mainly in the inability of either citizens or leaders to engage in serious debates about the public good. Here Douthat’s case study is the European Union, whose specialty is the politics of sclerosis. “If the Continent could have a common market,” he writes, mocking the EU’s utopian process of reasoning, “then it should naturally have a common currency as well. At a certain point, [however,] that optimism ceased to be justified, and the Eurocrats found themselves building the infrastructure of sclerosis.” Nor is the U.S. exempt from the disease. Both Democrats and Republicans display the symptoms in spades, but, of the two, he writes, a party “that nominates an erratic reality-television star and birther conspiracist for the presidency is probably making a special contribution to our decadence.”

And that brings us to repetition, the final source of decadence, to be seen everywhere in Western and, especially, American culture. “A society that generates a lot of bad movies need not be decadent,” Douthat allows. But “[a] society that just makes the same movies over and over again might be.” So it is that the wealthiest and most powerful entertainment business in history is now reduced to pumping out films in which cartoon characters invented two generations ago battle each other in more and more crossover formats. Spiderman against, or side by side with, Batman; Godzilla and the Incredible Hulk aligning to take out King Kong; repeat ad nauseam.

Even the revolutionist movements that occasionally disrupt this age of enervation are strangely imitative. At one provocative juncture, Douthat reflects on the growth and confidence of the young leftist militants in the U.S. who have recently engaged in violent protest. “The reason that the Antifa kids favor masks,” he postulates, “is that an awful lot of them are playacting their revolution.” Mimicking revolutionary myths of the past while knowing that they, too, will grow up one day and apply for jobs like the rest of us, they mask their identities as a preemptive career move—because “they don’t want to put their names and faces to something that’s fundamentally just a game.”

Surely, one concludes, this wretched state of affairs cannot go on. But is that right? According to a famous law formulated by the late economist Herbert Stein, things that cannot go on, won’t. In fact, as an academic friend of mine once pointed out, things that cannot go on very often do. Douthat himself wisely remarks that a society can be stuck in a decadent condition for a good amount of time. Whether the amount can be endless is debatable, though one could argue of course that endless decadence hasn’t been tried yet.

More than four centuries famously elapsed between the reign of Nero and the fall of Rome. “What fascinates and terrifies us about the Roman empire,” wrote W.H. Auden, “is not that it finally went smash” but rather that “it managed to last for four centuries without creativity, warmth, or hope.” To adapt a metaphor from American popular culture, the cartoon character may be suspended off the cliff’s edge for quite a long time, his feet still spinning in the motions of running, before gravity eventually does its work.

What are the factors that could sustain Western decadence? Too little remarked upon is the numbing of the American populace. By “numbing,” I don’t mean some abstract psychological indifference; I mean it in the most straightforward, pharmacological way. As an outsider I am always staggered by the ease with which a society that (to a European eye) still maintains a puritanical attitude toward alcohol regards the drugging of—for instance—smart and sparky children as entirely normal. Or the way in which Americans reach for medicine to dull human experiences such as grief. These examples (and one could adduce many more) are among the reasons that a soma-fed population à la Brave New World is able to get by without being asked (or asking itself) the questions that a population ought to be asking itself in order to escape decadence.

Douthat believes that even major events in world affairs have failed to shake us from our civilizational stupor. In a section titled “Waiting for the Barbarians,” he cites the once-common proposition that 9/11 and the War on Terror smashed post-cold-war liberal complacency as the West found in Islamic fundamentalism a global adversary on the scale of the Soviet Union. Douthat is at pains to refute this view—for the liberal establishment, the smashing of complacency occupied the merest flicker in time—but then he goes off on a tangent:

Such claims [regarding the Islamist menace] require imagining an Islamic world that’s expanding rather than convulsing; that’s consolidating rather than being consumed by civil wars, that’s winning converts within the West’s elite rather than primarily among its dropouts; that’s dramatically exceeding Western fertility rates rather than just converging with them. And all these imaginations are just that; fancies that bear no relationship to the actual state of Islamic alternatives to Western liberalism.

Douthat is himself too complacent. Shifting from geopolitical confrontation to the presence of unassimilable Islamist communities within the nations of the West, he declares at one point that

There are no Islamist Rosenbergs or Kim Philbys . . . [n]o Islamist analogue to Alger Hiss, and while Muslim intellectuals in the West sometimes engage in double-talk about the illiberal aspects of their faith, there is simply no Islamic equivalent of the Marxists who once populated Western academia and openly expected to undo the liberal capitalist order from within.

It would take another essay to rebut this assertion, and I have already done so at book-length. In brief, Douthat ought to spend more time in France or any other West European country to see if his claim holds up as well as it does in the United States.

But to return to the question of when our decadent age will either meet its own death or, facing the end, miraculously reverse itself, Douthat offers three potential triggers of the latter, salvific response. These are catastrophe, renaissance, and providence—or, as one might put it, a meteorite, a renewal of cultural vitality, or divine intervention in the form of a religious reawakening. Douthat clearly favors the last, though he sensibly offers no signposts for how it might come about.

If there is one big failing in The Decadent Society, it is this: the malaise Douthat rightly describes is an American product and an American export, a point he somehow misses. True, Europe has problems aplenty, including the barely fettered mass migration from the third world and a considerable failure at integrating the newcomers. True, too, the American economy, the American military, American technology, and at times even American statesmanship have given the world tremendous gifts. But on the subject of cultural sclerosis and enervation, Douthat is insufficiently open-eyed to the fact that much of the problem is an American invention that other American inventions have helped to pump around the world.

Let me illustrate with a single example from the realm of American art: Jeff Koons’s monumental sculpture, Bouquet of Tulips, his recent “gift” to the city of Paris—a city that might be said to have suffered enough in recent years. Koons’s work is at one and the same time crass, naïve, tasteless, and grotesque. Much worse, it is typical. Thanks to a very American idea about how to measure value in art, the art America is most famous for producing today is the art that sells for the most money. “Artists” like Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Jeff Koons, who singly or together have never created one work of greatness, have nevertheless created something else: an entire market for hedge funds to trade capital around. In the process, they and their customers have diverted art far away from any place in which it could be genuinely creative or great.

I could make a similar argument about American culture in general, with caveats perhaps only in the case of light music (in the early 20th century) and some literature. But surely the question must at some point be asked: why has the country that has contributed so much in certain areas produced less great art than almost any Italian city managed in a few decades during the Renaissance? Of course, the great enervation, if that is what we are going through, has many causes. But writing from Britain, I see the kid that has been at the top of the class for the last century failing to produce anything like the depth of thinking and creativity that ought to be reflective of its size or the one-time talents of its population.

Douthat, as mentioned, places his hopes for American renewal in religion: the spur, as he sees it, that will lift the country out of its decadence. But religion across the board is weaker in America than it once was. Though that, too, may change. Since Douthat’s book has come out, much has already altered. As economies shutter and hospitals fill up, perhaps the meteorite strike is in fact now upon us. And who knows whether or not that will spark the religious revival that Douthat longs for.

Whatever is to come, we shall see whether the crisis we have just entered proves Douthat’s views or not. And then we might know better how to understand the era we may have just left. One can predict nothing. But who knows, perhaps in the years to come we will feel some nostalgia for the decadent society in the knowledge of what can come after.

More about: Arts & Culture, Liberalism