Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Edward Grossman has a corona-related question. Citing the King James Version (KJV) of the verses in the 91st Psalm, “Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day; nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday,” Mr. Grossman inquires about the Hebrew word that is translated by the KJV as “pestilence,” dever. How, he wants to know, if at all, does dever differ from mageyfah, another biblical word, usually rendered by the King James Version as “plague,” that means epidemic in modern Hebrew?

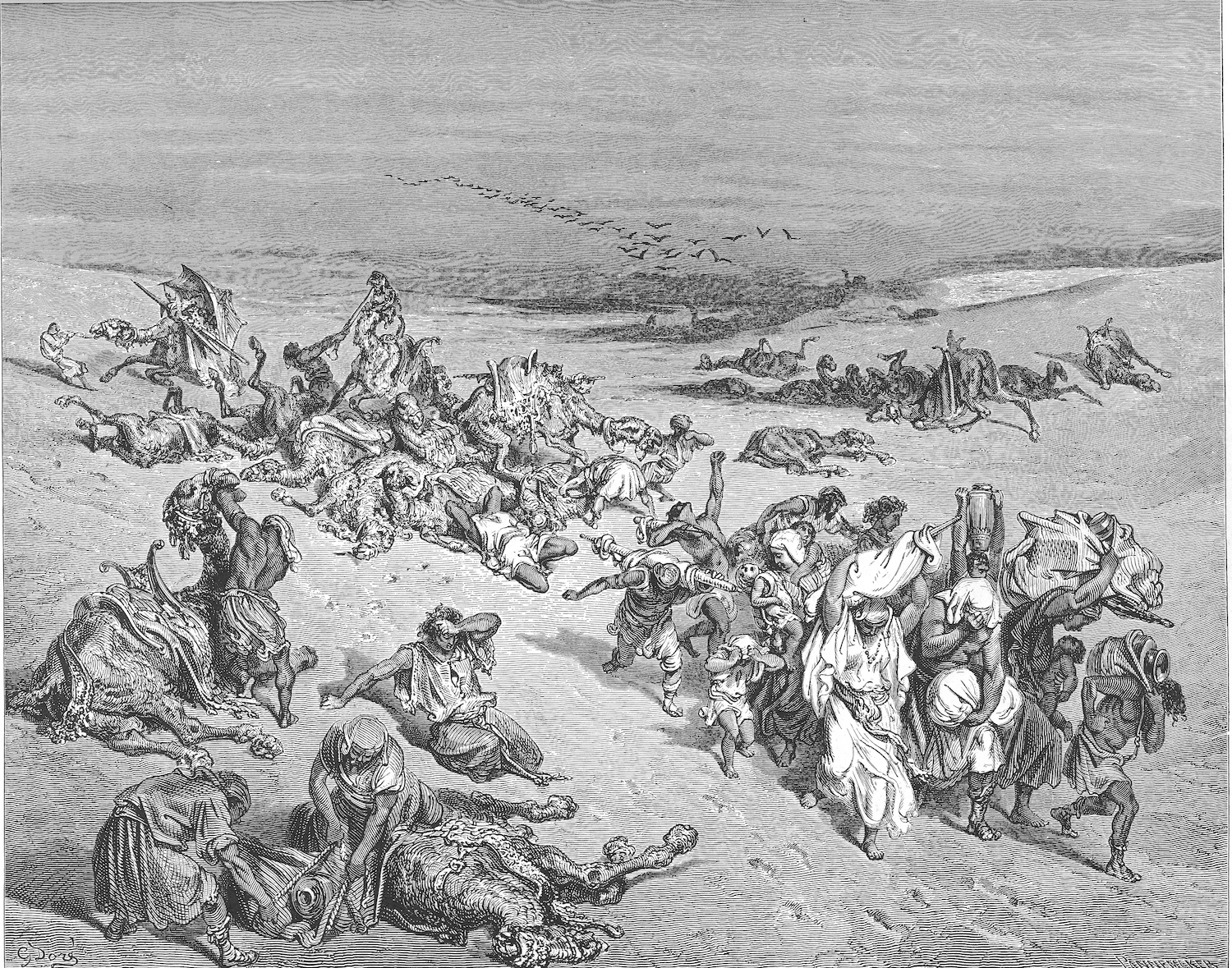

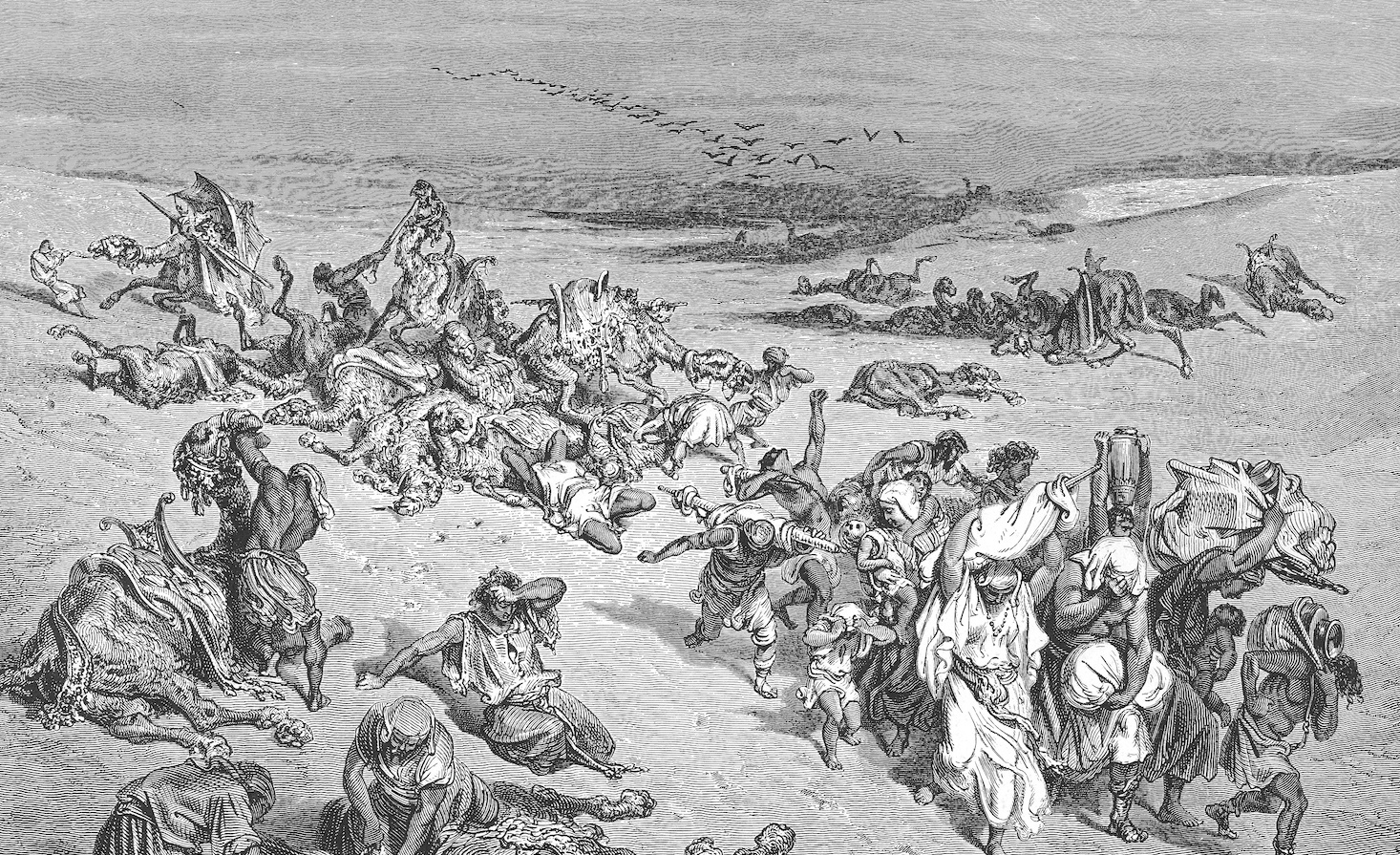

This is, of course, a Passover-related question too, since dever—its full description in the book of Exodus is dever kaved m’od, “a very heavy dever”—was, according to the book of Exodus, the fifth of the ten plagues visited by God upon the Egyptians. When we recite the list of the plagues in the Haggadah at the seder table, flicking a drop of wine onto our plates for each of them, dever comes between arov and sh’ḥin. The latter, generally translated as “boils,” is stated by the Bible to be an eruptive skin condition; but the nature of arov is unclear.

Arov would appear to derive from the Hebrew verb l’arev, “to mix.” The early-Common Era midrashic compilation of Exodus Rabbah speaks of two different interpretations of the word. Rabbi Yehudah takes it to denote a mixture of wild beasts; Rabbi Nehemiah, a mixture of stinging insects. Although Nehemiah’s reading may be the older of the two (the BCE Greek Septuagint, made in Egypt by Jewish translators, renders arov as kynomuia, “dog-fly”), Jewish tradition eventually came down on Yehudah’s side.

Christian exegetes, however, preferred Nehemiah’s interpretation, which is why the KJV renders arov as “a swarm of flies.” This indeed makes more sense in the context of the ancient Nile Delta inhabited by the Israelites, an intensely cultivated area in which lions, leopards, and bears (the three beasts cited by Yehudah) were not a menace. Indeed, the 1917 Jewish Publication Society Bible, as well as its 1986 revision, accepts Nehemiah’s opinion, as do some contemporary Haggadahs. Robert Alter’s more recently completed Hebrew Bible, for its part, chooses to sidestep the debate by opting for a “horde” of noxious beings without venturing to say what they were.

But let’s get back to Mr. Grossman’s question. Does dever signify a specific disease, or is it simply a generic word for a contagion and therefore a synonym of mageyfah?

If we were to restrict ourselves to the dever of Exodus, a case could be made for specificity. The Bible tells us that, in the plague of dever in Egypt, “the hand of the Lord [was] upon the cattle in the field, upon the horses, upon the camels, upon the oxen, and upon the sheep”—in other words, that this was an illness of domestic ruminants that did not spread to human beings. It could have been rinderpest, hoof-and-mouth disease, or something similar.

Yet in all of the other places in the Bible where the word occurs, dever does affect humans. Thus, for example, in a story in the final chapter of 2Samuel about how God punishes King David for ordering a census for which he lacked divine permission, we are told that 77,000 Israelites perished in the ensuing dever, while Deuteronomy 28:21 warns the people of Israel that, if they disobey God’s word, “the Lord shall make the dever cleave unto thee, until it hath consumed thee from off the land.”

Few Bible translations have sought to distinguish between the dever that struck the domestic animals of Egypt and the dever that attacks humankind. The Septuagint, the world’s oldest translation of the Bible, renders dever everywhere as ho thanatos, “the death,” preferring it to the ancient Greek words for plague or pestilence nosos and loimos. Its example is followed by the second-oldest Bible translation, the Aramaic Targum, which gives us mota, also meaning “death.” (In Middle English “the death” was sometimes also used in this fashion, as in “the Black Death,” the devastating bubonic plague that swept Europe and Asia in the 1300s.)

The Latin Vulgate translates dever consistently as pestilentia. In English Bible translation, however, the practice developed of using different words for the dever of Exodus and the dever of Deuteronomy, Samuel, and elsewhere. This started with William Tyndale’s 16th-century Bible, which termed the dever kaved m’od that struck Egypt “a mighty great murrain.” The KJV retained Tyndale’s “murrain” while changing “mighty great” to “very grievous.”

Murrain, pronounced MUH-rin, is a word for dever that some of you may still find in your Haggadahs, though only, I suspect, if these have been in your family for quite a while. As a child, I remember encountering it every year at the seder and wondering what on earth it meant. Also spelled murreyne, morreyne, and moren, it entered English in the 13th century from the now-archaic French morine, a cattle plague. Ultimately, it derives from Latin mors, death, as does Latin mortalitas, a plague or pestilence, parallel to thanatos and mota.

In the end, Mr. Grossman, dever and mageyfah do mean pretty much the same thing. Yet I find it significant that you chose to ask about dever (which in late medieval Hebrew came to refer, as it still does in modern Hebrew, to bubonic plague) as it occurs in Psalms rather than in some other book of the Bible. It has always been a Jewish custom to recite chapters of Psalms in times of fear or danger, and “Thou shalt not be afraid of the pestilence that walketh in darkness” is certainly a more comforting verse than “the Lord shall make the pestilence cleave unto thee.” It isn’t easy not to be afraid these days, but a Psalm like the 91st can help.

I don’t know if it is realistic in this time of plague to wish readers, as I do every year, a happy Passover. Let it but be a healthy one and we can say, along with the Haggadah, dayeynu.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Arts & Culture, Exodus, Hebrew Bible, Passover, Ten Plagues