One of the occasional gifts of life as an art critic is the opportunity to rescue from oblivion the work of a relatively unknown artist. In this case, unknown to oneself—for, until recently, and despite having written about Jewish art for nearly two decades, I’d been virtually unacquainted with Marc Klionsky, who was born in Russia in 1927 and from 1974 until his death in 2017 lived and painted in New York City. Today, the more I’ve become acquainted with his work, the more I’m reminded of the plea entered by Willy Loman’s devoted wife in Death of a Salesman: “Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a person.”

Unlike the pathetic Linda Loman, Klionsky’s widow Irina speaks dotingly of her husband’s life as a series of miracles. In 1941, the Minsk-born fourteen-year-old, who had evinced artistic promise from an early age, fled the approaching Nazis with his family and 200 other members of the Jewish community to settle in Kazan (now the capital of Russian Tatarstan). At the end of the war, the young Klionsky moved to Leningrad, soon to become the star student at the city’s academy of fine arts. In the wave of regime-sponsored anti-Semitism stirred up by the so-called “Doctors’ Plot,” he was forced out, only to be readmitted after Stalin’s death in 1953. Graduating with honors, he went on, in a first for a Jew, to postgraduate studies at the same academy.

Having set up shop as a working artist, Klionsky earned regular commissions from the Soviet Ministry of Culture, creating social-realist and propagandistic works. In Youth, for example, a young man dressed in khaki climbs a ladder into the painting; on a platform above, a joyous young woman holds her billowing hair in her hands as she takes in the view. But he was constrained from touching the themes most dear to him: namely, Jewish life and Zionism.

By 1961, however, stirred by a close call with a tumor, he resolved to focus on what he saw as his greater purpose in art: to depict the devastating impact on Jewry of the Holocaust. He realized this ambition in a series of secret prints and engravings that he collectively titled Lest People Forget. In technique, these recall the lithographs of Honoré Daumier; in subject matter, the intensely haunting war drawings of the German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945).

When some of Klionsky’s work came to be included in an exhibit at a London gallery, Klionsky was hauled into a KGB office and interrogated by an official demanding to know how this breach of Moscow’s iron protocols had occurred. Although he talked his way out of the jam, he knew he was on the KGB’s radar—and that it was time to leave. (Later, the London dealer, Eric Estorick, would arrange for a joint show of Klionsky and Marc Chagall.)

More “miracles” loomed. In 1974, as Klionsky, his wife, and their two daughters readied themselves for emigration to the U.S., he managed to secrete many of the Jewish sketches and prints amid piles of works on “secular” subjects—and then to convince unsuspecting officials to stamp the backs for clearance without inspecting each one. Unfortunately, the engraving plates had to stay behind, thrown into the river by Klionsky himself. Among the roughly 300 paintings and 1,500 works on paper in his widow’s possession today, some still bear their exit stamps.

Nor was that the final miracle. A Russian gallerist from whom Klionsky was gathering some of his unsold works stuck her neck out for him by confiding the name of the employer of an overseas collector who had purchased multiple paintings. By chance, in the Klionskys’ first week in New York, they would meet someone who knew someone who knew the mysterious buyer.

A year after moving to New York, Klionsky went on an official trip to Israel to paint one of the last portraits for which Golda Meir would sit. For this and other, subsequent portraits he attracted the notice of the critic John Russell at the New York Times, who in 1988 would gush: “Marc Klionsky is one of the best portraitists around, and he has an astute eye for the body language of people who cannot quite talk their way through their difficulties.”

In that same year, the great jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie sat for a portrait that hangs today in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. Two years earlier, Klionsky had designed a commemorative Nobel Peace Prize medal for Elie Wiesel, whose portrait he also painted. Years later, in the introduction to a 2004 book about Klionsky, Wiesel wrote:

I dream of Rabbi Naḥman of Bratslav for whom everything had a heart: the heart itself has a heart, he said. For Marc, the face also has a face; the latter alone makes us guess its upsetting secret of truth.

In view of all this, it’s surprising that Klionsky’s name is absent today from the websites of the Jewish Museum and the Museum of Jewish Heritage, both in New York, as well as of the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, and the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. An exception is Yeshiva University Museum in New York, whose collection includes an undated, expressionist painting titled The Fiddler. Another tantalizing exception may be the embassy of Saudi Arabia in Washington, which owns Klionsky’s 1995 portrait of Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi prince and former ambassador to the United States. (The embassy didn’t respond to my query.)

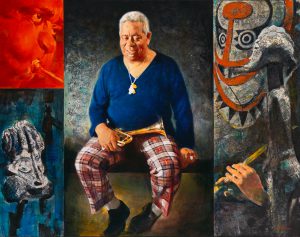

For a taste of Klionsky’s art, let’s dwell briefly on the portrait of Dizzy Gillespie that hangs in the exhibit Bravo! on the third floor of the National Portrait Gallery. Nearby are renderings of such familiar performers as Joan Baez, Elvis Presley, Bob Hope, and Grace Kelly. Klionsky’s portrait is one of the show’s most nuanced.

In what is a sort of triptych, the center section, the work’s largest, shows the seated Gillespie wearing a blue shirt and plaid pants, his trumpet on his lap and a half-smile on his face, his eyes looking down and away from the viewer. From a distance the brushwork appears deceptively slick; up close, one can admire the artist’s masterful mingling of calligraphic lines with bold strokes of color that he doesn’t trouble to pretty up. In the painting’s left-hand panel, the top corner gives us a different, zoomed-in portrait of Gillespie’s face as, cheeks puffed out, he plays the trumpet; this entire segment is rendered in red and yellow, with a yellow squiggle on the mouthpiece making practically an abstract painting all its own.

In talking with Gillespie prior to painting the portrait, Klionsky came to appreciate the African (and Afro-Indonesian) influences on his music. These are reflected here in imagery he may have gleaned in visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the triptych’s right-hand panel, Klionsky gives us in meticulous closeup a figure holding a wooden flute, a large early-20th century mask created by the Elema peoples of Papua New Guinea, and a smaller sculpted figure whose protruding chin recalls the work of the Senufo peoples of the Ivory Coast. In the bottom corner of the left-hand panel we find another mask, this one a 19th-century creation from Cameroon. Thus, overall, we have the full man in the middle of the portrait and on the edges a flavor of what his music means and whence it came.

Standing in Klionsky’s former studio in lower Manhattan, I noticed, hanging from the ceiling, a large rectangular graphite drawing: the artist’s vision for a Holocaust memorial. Sadly never realized, it provides a key to understanding his mind as an artist and his soul as, in particular, a Jewish artist.

Massive stones form the Hebrew word “remember” (zakhor), dwarfing the pedestrians crouched below in a manner reminiscent of the biblical spies in the book of Numbers who in reporting back to Moses describe themselves as feeling like grasshoppers in comparison with the plus-sized Canaanites. From the depths of the drawing there emerge a tallit and two arms clutching a rifle. Klionsky’s ultimate ambition, I learned from his family, was to create an entire park on the same monumental scale.

I began to daydream about what such a monument would look like on the National Mall. At a time when Jewish blood has once again become cheap, its title could be De Profundis (Latin) or mi-ma’amakim (Hebrew, Psalm 130): from out of the depths. As it is, the sketch offers one of art history’s most powerful illustrations of, simultaneously, “Never Forget” and “Never Again.”

On a smaller scale but no less momentous is Waiting for the Train (1986), at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. On the right, a very pregnant woman with a toddler in a stroller stands with three other children on a New York City subway platform as if looking expectantly for a train. Above and behind her, a “Transfer” sign with an arrow directing passengers to a number-6 train creates a near-halo around her head. Extreme light and shadow make the figures appear to be on stage, with the viewer gazing slightly upward at them either from the pit below, as it were, or from the window of a train newly arriving.

On the left side, a Jewish boy in oversized clothing and a newsboy cap throws something or picks something up; behind him, several Jews wearing yellow stars emerge from the shadows of a train marked “1107.” Past and present seem mutually oblivious, each of the other, but the Jewish figures on the left appear at least somewhat aware of their fate while the mother on the right deals grimly with the complicated challenge of navigating the city with young children in tow and another on the way.

Beyond its ominous layering of past and present, of concentration camp and New York City, the painting displays much technical prowess. Thus, the sharp diagonal of the Jewish boy’s arm on the left balances the corresponding angle of the stroller frame on the right, forming a triangle that culminates below a heavy vertical line that functions as a kind of barrier between past and present while also forming an arrow that echoes, in reverse, the arrow on the Transfer sign above.

A symphony of deep shadows, indifferent to chronology, crisscrosses this composition; throughout, hats and eyes reverberate. The palette is such as to leave one thinking that a bit of the color on the right has begun to animate the sepia tone on the left. It’s hard to visualize such a balance, but in this work Klionsky has seamlessly collaged the beautiful and the terrifying—just as, throughout his artistic career, he was haunted by the amalgamation of prayer with the need, and the duty, to arm oneself.

In pursuing their familial duty of securing the late artist’s legacy, Klionsky’s widow, daughter, and grandson have their work cut out for them. Still, in light of his many accomplishments, there’s plenty to work with. The admonitory title of his sketches and prints, Lest People Forget, applies both to Klionsky’s chosen Jewish subjects and to the artist who imagined and created them.

More about: Art, Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Painting