We present here another scene from the life of the fictional Israeli military governor Colonel Kranzdorf, who has previously appeared in Mosaic here.

In this story, set around the year 1980, Kranzdorf visits Arlington National Cemetery, where, since the American Civil War, soldiers who honorably served the United States have been laid to rest. The site of the cemetery once belonged to the family of Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army, whose wife, Mary Anna Custis Lee, was a descendant of Martha Washington. Thus, the site evokes the deepest memories of the American republic, the troubled history of its Civil War; and from the beginning of its current use, the site has been dedicated by the remains of the servicemen who gave their lives for its enduring freedom to the union of the United States.—The Editors

In spite of Daisy’s recommendation he and Esther kept the Ford. She’d cautioned them, first, never to stop for hitchhikers on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line—there were maniacs in the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave. Also she’d warned against entering the South displaying New York plates. They must switch in D.C. for another Hertz car, one licensed in Virginia. Really? Yes, really—more than a century after the Civil War, she’d let them know, and more than a decade after segregation was ended at the point of U.S. Army bayonets many whites in the South continued hating Yankees, especially race-mixing Jewish Yankees. But the Israelis had taken a liking to the Ford, and when the colonel said he’d rather keep it Esther didn’t object.

They reloaded it and crossed the Potomac with her at the wheel and on Kranzdorf’s initiative they visited the national cemetery in Arlington. He wanted to see the grave of Charles Orde Wingate, major-general, British army, the Nonconformist godfather of the IDF he’d seen alive with his own seven-year-old eyes. A complimentary map and brochure were provided at the visitors center. The woman at the desk indicated the route to the grave on the map, and, sharp-eyed or blessed with excellent hearing, offered a go-cart. No, thank you. And so he and Esther walked in past a sign:

PLEASE

CONDUCT YOURSELVES

WITH DIGNITY AND RESPECT

AT ALL TIMES

The cemetery was near the airport—every few minutes a Jumbo or whatever landed or took off. Limping, hobbling, the colonel squeaked along beside her past ranks of thousands, tens of thousands, of precisely-spaced gravestones spreading into the hills. All those in the military area of the national cemetery in Jerusalem had a sword, an olive branch, and a Star of David engraved—including Rafik’s, inscribed in both Hebrew and Arabic in the separate Druze portion. Whereas here nearly all were engraved with crosses. And there were dozens of various memorials.

Limping, hobbling, squeaking until the Englishman was found. Orde didn’t rest by himself. Eight names chiseled into the long stone, and “DIED IN AIRPLANE CRASH, WWII March 24, 1944.” Meaning, the governor reminded his wife, the crash of a U.S. Army Air Corps plane which failed over the Burmese jungle, leaving the American and British dead mixed up, indistinguishable, so all together here in what in Hebrew is called a “kever aḥim,” literally “a grave of brothers.”

And in Kranzdorf’s mother tongue? “Massengrab?” Not quite the equivalent, he’d say. “Grab der Brüder” or “brüderliches Grab” more like it. As he and Esther stood there a ragged “V” formation of geese honked overhead, northward bound, and then another. Didn’t geese ever get sucked into a jet engine? No need to tell her again how as a seven-year-old refugee-immigrant he’d seen the encampment at Ein Harod where the half-mad Wingate, a Christian, a friend of the Jews, trained the Jews, the new Jews of Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel, to fight and kill mercilessly, especially at night.

He left a pebble on Wingate’s grave, Jewish-style, and music was heard. Yes—a small band in uniform, followed by a gun carriage on which rested a coffin wrapped in the Stars and Stripes, two black horses pulling it, followed by an honor guard, followed by the family, the friends, the comrades-in-arms. The colonel and Esther watched. Its embassy in Tehran was occupied and its diplomats, Marines, businessmen, and spies taken hostage, but no wars being fought by the U.S. just then, so it had to be a veteran of the Second World War, the one Henry Miller prayed the U.S. would lose, if not actually of the first, or of Korea at the most recent, probably not Vietnam but who knows. Canes, bald heads, white hair, and silvery hair among the mourners. No clergy, or no obvious clergy, although at home, except for burials of soldiers in kibbutz graveyards, there was unfailingly an IDF rabbi or a Druze sheikh. Esther and he watched the mini-parade reach the grave, the coffin being offloaded and lowered, and saw and heard the riflemen—three whites, one black—fire three volleys, as was done at home, and taps played, unlike at home.

Kranzdorf took a picture of the kever aḥim after which the Israelis roamed a bit.

True, nearly all the gravestones had a cross engraved. Nearly but not all. Take for instance this one bearing the Star of David:

IN MEMORY OF

Charles Ojserkis

S2C

US Navy

Jun 10, 1920-May 3, 1943

Purple Heart

USS Cythera

In memory of? Signifying what? Did they never find Charles’s body? Kranzdorf guessed the twenty-three-year-old went to the bottom of the Atlantic or Pacific with the Cythera.

Or this, also marked with a Star of David:

MONTY EREZA

1st Lieutenant

United States Infantry

Dec 16, 1916-Jan 18, 1945

Right at the end of the war, the governor noted. Where did twenty-nine-year-old Monty fall? On some Pacific island or in the Rhineland? Yes, in all militaries the lieutenants worth their salt get killed quicker than all other ranks. Killed or if lucky wounded. His first, his trifling wound Kranzdorf had come by as a young lieutenant, probably the result of friendly fire. A lucky wound in more than one sense—thanks to it he met the even younger Esther Toledano, a Hadassah nurse. Charles and Monty, two young men, two young Jews dead in a war Miller had hoped the U.S. would lose.

Miller had said all wars were idiotic. The colonel believed some are, some aren’t. Was the First World War, in which Uncle Otto had won two Iron Crosses and Kipling had pulled strings so his nearsighted son could enlist? Kipling a jingo who’d mocked the pacifists and whose heart was broken when that only son of his was killed. Never had Kranzdorf who was the father of two daughters, and no sons, and one brand-new grandson romanticized war. But although he had Graves, Owen, Sassoon, Rosenberg, Hemingway, Céline, Jünger, Remarque, and Kraus in his library at home in English, French, and German, and although Paths of Glory with Kirk Douglas had had an impact on him, a terrific film, the governor wasn’t a pacifist.

Of course not—he was a dawk, or a hove, but not a man rejecting war entirely. He hated Germany and the Germans, or at least most Germans older than, say, sixty, no, better make that fifty, so in his eyes it wasn’t the 1914-1918 meat grinder but how it was conducted by the Allied generals that was idiotic. Pacifism? A luxury, especially for Jews. Not all of the IDF’s battles had been wisely fought, in his opinion, an opinion he’d made some enemies by never hiding, but so far none of Israel’s wars had been crazy like the American war in Vietnam dreamed up by John Kennedy.

That glamorous, decorated, assassinated war veteran who ignored Dwight David Eisenhower’s warning never to get into a land war in Asia. Should the colonel and Esther go see JFK’s resting place? According to the map it would’ve necessitated a serious hike, and though his leg wasn’t truly disabling she said they didn’t have to. Instead on the way back they happened on a Baroque memorial to the fallen of the losing side in the Civil War, the side Miller preferred.

TO OUR DEAD HEROES

BY

THE UNITED DAUGHTERS

OF THE CONFEDERACY

About this war Esther knew only Gone With the Wind starring Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh. The bronze figure of a woman atop the monument held a plow and a laurel wreath. On the plinth the verse: “And they shall beat their swords into plow shares and their spears into pruning hooks.” The colonel reminded his wife of Isaiah’s original: “V’khit’tu ḥarvotam l’itim/ va-ḥanitotehem l’mazmerot.” Quite a number of engravings on this monument, really. This also: “Victrix Causa Diis Placuit Sed Victa Catoni.” He translated into Hebrew for her, and explained the reference, and she had to agree it was defiant, unbowed. And this, in raised lettering:

NOT FOR FAME OR REWARD

NOT FOR PLACE OR FOR RANK

NOT LURED BY AMBITION

OR GOADED BY NECESSITY

BUT IN SIMPLE

OBEDIENCE TO DUTY

AS THEY UNDERSTOOD IT

THESE MEN SUFFERED ALL

SACRIFICED ALL

DARED ALL—AND DIED

And in raised letters:

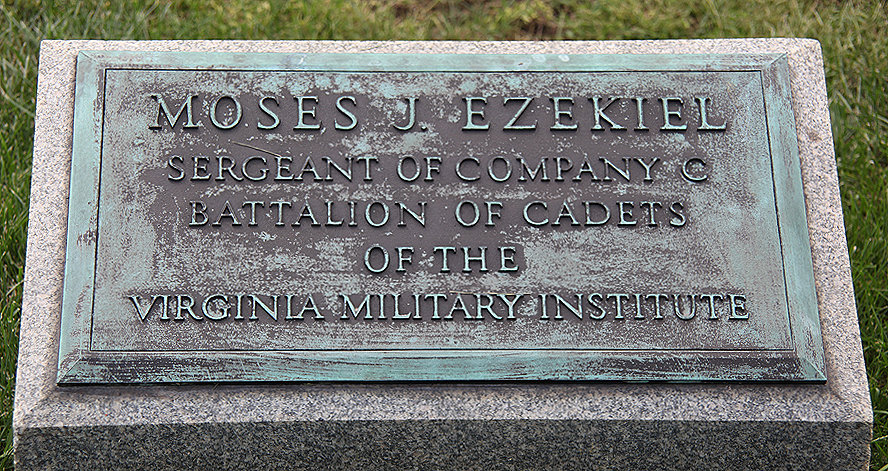

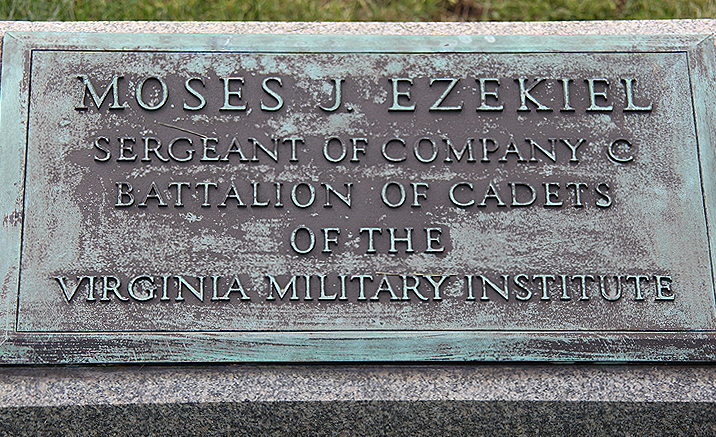

Ezekiel Sculptor

Rome MCMXII

and:

MADE BY

AKTIEN-GESELLSCHAFT GLADENBECK

BRONZE FOUNDERY

BERLIN-FRIEDRICHSHAGEN-GERMANY

Ezekiel? This according to the brochure was Moses Ezekiel, ex-sergeant in the Confederate army. A rebel and a Jew? Well, no Star of David on his own gravestone near the memorial he designed, but the colonel suspected yes. He remarked to Esther that the Southerners including maybe this Ezekiel were men fighting brilliantly to preserve an evil system, no? What did she think? Should this monument be here? Well, she answered, maybe it was intended to reconcile, to heal wounds.

Author’s Note: Some distant kin of Ezekiel, who in fact was Jewish, have now called for the monument to be removed. They made no mention of his bones or those of the other Confederates buried around it.

More about: American Civil War, American Judaism, Arlington National Cemetery, Arts & Culture, History & Ideas