From Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin, 1504.

This is part two of a two-part essay on the depiction of the Temples in Jerusalem in art made primarily for Christians. Part one, which outlined the concepts this part provides examples for, is available here.

In the first part of this examination of the depiction of the Temple in Jerusalem in Renaissance painting, we saw that it very often took on architectural features of the 7th-century monument erected on the physical site of the Temple Mount, the Dome of the Rock. Northern and Southern Renaissance painters adapted the dome design to the religious, historical, and aesthetic sensibilities of their time and place. And we brought that discussion to a close by observing the dilemma felt by painters—Northern and Southern—for whom sanctified, religious space was defined by graven images that they thought the Jews were prohibited to display.

Keeping all this in mind, I want to examine and juxtapose two Renaissance depictions of the imagined Jewish Temple. The first is an example from the Northern Renaissance: “The Miracle of the Rod and the Betrothal of the Virgin” by Robert Campin. Painted between 1420-30, it is now housed in the Prado in Madrid.

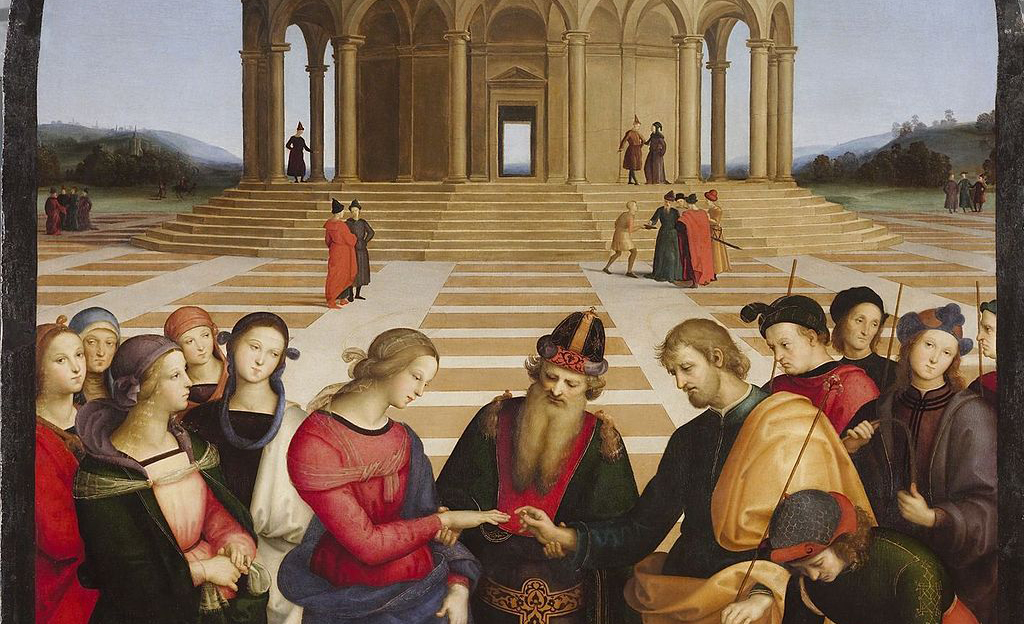

To Campin’s work I will compare a painting by Raphael Sanzio da Urbino, one of the most distinguished masters of Renaissance. His much more famous rendition of the same two episodes joined in a single scene, and usually given the title “The Marriage of the Virgin.” This work, dated 1504, is currently in the Brera, Milan.

In the second part of this examination, I’ll consider the architectural style and decoration of these two works—separated by almost a century and by a thousand miles as the crow flies—in order to assess how the religious imagination of Renaissance Italy related to Judaism.

First, it is necessary to review the story being portrayed in each work. Both Campin’s and Raphael’s paintings depict a famous Christian miracle, that of Joseph’s flowering rod, and the ensuing betrothal (or marriage) of Joseph and Mary. The story is from the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James (c. 150 CE) According to this text, the Virgin Mary had been offered by her parents to the Temple, where she resides with a group of other virgins from the age of three. When she turns fourteen, the high priest Zachariah, garbed in the priestly vestments, is instructed by an angel of the Lord in the Holy of Holies that he is to find a husband for her. Zachariah is told to gather representatives of the Israelites, each with his staff, whereupon, he is assured, a sign will be given that one of them is Mary’s destined bridegroom.

Joseph, “throwing down his ax,” goes out to join them. The high priest gathers all the rods, brings them into the Temple, and prays. He then re-emerges and returns each rod to its owner. None show any sign of change, save that of Joseph: “Finally, Joseph took his rod. Suddenly, a dove came out of the rod and stood on Joseph’s head. And the high priest said, ‘Joseph! Joseph! You have been chosen by lot to take the virgin into your own keeping.’ Joseph, anxious about his betrothal to the much younger Mary, worries . . . ‘I have sons and am old, while she is young. I will not be ridiculed among the children of Israel’” (9:5-8). The high priest warns him that if he disobeys the sign, divine wrath will pursue him as it did the rebels of Korah’s party (Numbers 16). Chastised by fear of punishment, he takes Mary to his house, where she spins scarlet wool for the Temple veil, and he goes out “to build houses.” Shortly thereafter, when Joseph is away, an angel announces to Mary the impending birth of her son.

The account of the miracle of the rod is repeated in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (ca. 7th century). In this telling, Joseph does not need to be coerced by threat of punishment. Pseudo-Matthew portrays him as self-effacing, adding details such as the fact that Joseph’s rod was the shortest, and left on the altar by the high priest after Joseph bashfully neglected to return to claim it, so in doubt was he of his suitability as a husband of a fourteen-year-old virgin. The disparity between these portrayals of Joseph testifies to the wide spectrum of attitudes towards him in medieval textual and visual lore—he can appear as anything from blind cuckolded buffoon, to temperate, long-suffering and saintly.

The tale was known throughout Europe in the Middle Ages through The Golden Legend, composed in approximately 1260 by the Italian Dominican Jacobus de Voragine, who eventually became the archbishop of Genoa. It is in the account in the The Golden Legend that the rod of Joseph—unique among the other suitors’ rods—flowers while resting on the altar in the setting of our study, the Temple.

The architecture of the Temple dominates Campin’s “The Miracle of the Rod and the Betrothal of the Virgin.” The interior, on the left of the painting, contains features influenced by the Dome of the Rock; the façade, on the right side of the painting, is cathedral-like. Notice how Campin separates the scene of the “Miracle of the Rod,” which transpires in the domed simulacrum of the Jewish Temple, from that of the “Betrothal of the Virgin,” which occurs before the yet-unfinished façade of a Gothic cathedral.

Let’s focus on how Campin renders the Jewish space of the Temple. In order to make it recognizable as the primeval form and model for the cathedral, Campin invented “Jewish devotional images” from whole cloth. Thus, the architecture and furnishings of the Temple contain images, but not images of Jesus. The content of these images is conceptualized as “Jewish,” in the sense that they come from Hebrew scripture. The particular subjects were chosen both to highlight the violence of the era before Grace, and to foreshadow the coming of Christ. Thus, as usual in Christian art of the medieval and Renaissance periods, the Jewish past was acknowledged, but also represented as unaware of its own incompletion.

These Jewish images, forming the backdrop of Jewish worship, seem to murmur in the background, insinuating the clannishness, jealously, heresy, and enmity of the Jews. But these particular images bear a theological rebuke, too. Jews—including the high priest in archiepiscopal garb—are depicted as worshiping among objects portraying a history they regard as their own, depicting a Scripture of which they boast privileged familiarity. Yet, they remain ignorant of the fact that, right under their noses, the very objects with which they surround themselves proclaim Christ through the typological stories they tell. In a Christian reading, Cain, for instance, represents the Jews and Abel, Jesus; Samson destroying the Philistine temple is Christ bringing down the Synagogue; and David—Jesus’ ancestor—embodies the New Dispensation of Grace, destroying the grotesque and overgrown giant who personifies the top-heavy edifice of the Old Dispensation of the Hebrew Law.

Now, let’s have a look at the Jewish figures that Campin portrays. The actual Jews depicted in Campin’s Temple space are exotically and extravagantly garbed, with pointed hats, non-European features, bizarre coiffures, and a variety of sartorial clues to their gross and stupid (or wily and deceptive) materialism, their criminal ruffianism, and above all, their general otherness. They can be obscenely obese, disturbingly bony, or simply stupid-looking, like the high priest marrying Mary and Joseph, with his unshaven jowls and donkey-like gaze. They group together, hissing their slander jealously and conspiratorially, exhibiting baleful glances, with ugly faces and hateful gestures—all the hallmarks of what Joseph Leo Koerner has characterized as “enemy painting.”

The hostility of the image extends even to Joseph. As mentioned, Joseph was represented in a wide and diverse spectrum of ways during the Middle Ages. As a transitional figure, appearing in both the “old” and the “new” registers of the painting, he could have been depicted more honorably, but Campin chose to show him unshaven, frowning and with a closely cropped head—a type identified by scholars of medieval physiognomy as a criminal.

Both Joseph and the other Jews appear in deliberate contradistinction to the few members of the Holy Family designated and delineated as “proto-Christians” in spite of their clear Jewishness in the text of the Gospels. These figures are more pleasant to look upon than “the Jews,” and comport themselves with refinement. The decadence and decay of the Old is brought into even sharper focus when contrasted with the New; the heavy burden of Law, when compared with the lightness and joy of Grace.

In Raphael’s “The Marriage of the Virgin,” the Temple lacks any cathedral-like features. Its architecture is more immediately influenced by the Dome of the Rock and contemporary Renaissance neoclassical architecture, notably the small commemorative monument to the martyrdom of St. Peter, called the Tempietto, designed by Donato Bramante and built in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio on the Janiculum Hill in Rome in 1502.

We’ll return to Raphael’s portrayal of the Temple in detail shortly. But the very first thing we notice when we juxtapose Campin’s painting with Raphael’s is that the latter seems, on the surface, to be much less hostile. This is due, of course, to the legendary “polish” of Raphael’s works, from which passionate emotion (and indeed anything ugly or imbalanced) seems to be banished. Even the much-remarked-on suitor breaking his rod is famously balletic in the midst of his violent act. But the lack of polemic here is also a result of the fact that in Italy, simple typology does the heavy lifting of Christian supersessionist theology as opposed to the overtly hostile mode of “enemy painting” we encounter in the North.

To illustrate the polemical work done by typology, let’s briefly look at Mantegna’s Circumcision of Jesus of 1461, now in the Uffizi in Florence.

In this painting, we are afforded an interior view of the Jewish Temple, represented as a spacious, high-ceilinged classical edifice clad in porphyry, onyx, and marble, full of cornucopia, swags, wreaths, vases, and vines. On the wall above the scene, in the tympana of two Roman arches, are painted, as if in low gilded relief against black onyx backgrounds, the scene of the Binding of Isaac at left, and of Moses bringing the Tablets of the Law to the Israelites on the right. In the spandrel between the arches, the painter depicts another low relief, this one in red porphyry, of a six-winged seraph. The altar itself is not free-standing, but is represented as a shallow, chest-high marble box against a wall, as if in one of the side-chapels of a neoclassical church or cathedral.

The architectural envelope broadcasts “antiquity” and the decoration contextualizes that antiquity as Jewish. The scenes chosen from the Old Testament are intended to situate the ritual depicted in the setting of its sacred pre-history. Circumcision was enjoined upon Abraham, it was confirmed by Moses, it is now submitted to by Jesus as a foreshadowing of his eventual abuse at his Passion at the hands of “the Jews.” Still, the painting is reasonably free of diatribe: Mary is classically beautiful, as might be expected. But in contradistinction to the work of Campin and other northerners, the male protagonists—the high priest, who embodies “the Jews,” and Joseph, a transitional figure—while somewhat hunched and round-shouldered, old, and tired-looking—are still reasonably dignified. As we’ve noted, the architecture evokes the antique, but the revival of interest in the antique in Mantegna’s day makes the painting into something that is simultaneously plausible as contemporary. Mantegna’s is the once and future Temple as pagan/Jewish synthesis.

With Mantegna as a reference, we can now return to Raphael’s “Marriage of the Virgin” in order to see the pagan/Jewish synthesis taken to its logical extreme. The painting appears to lack any overt iconographic evocations of Old versus New. Some of the figures depicted in the background sport strange or pointed headgear, but none evince aggressive countenances or gestures. This seems to depart radically from the hostile typological model of Campin and even its milder version in Mantegna.

In its preternatural calm, Raphael purges what is ostensibly a depiction of the Jewish Temple of any iconography related to Judaism—indeed, of any iconography at all. Raphael’s Tempietto is symbolic, open. Aside from the classicizing details of snail volutes, it contains no furniture, no ornaments, no ritual space, no altar, no images, only a view onto the endlessly receding horizon.

Raphael did not need to imagine accoutrements of Jewish worship, as Campin did. We know that he was aware of the “historically accurate” furnishings of the Jewish Temple because he painted that building in an historicizing fashion on another occasion. In “The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple,” a fresco he created between 1511 and 1513 as part of the commission to decorate the rooms of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, the Jewish Temple appears replete with high priest in full regalia, the Ark, the menorah, the altar, and the other Temple vessels.

Raphael was also familiar with the proper furnishings of a pagan temple. In 1515, he painted what we might call a “true” Graeco-Roman temple, because it bristles with appropriate statuary—armed and helmeted gods and voluptuous goddesses. That temple appears in his “Paul Preaching in Athens, at the Areopagus,” currently in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Again, that image is very dissimilar to the Temple shown in “The Marriage of the Virgin,” which depicts a classical tempietto without any of the statuary that would identify it as a site of pagan worship.

Given that he had previously painted both the Jewish Temple, with its distinctive Jewish features, and pagan temples, with their divinities and statuary, it would seem to be a deliberate choice on Raphael’s part to be doing something else here altogether. Exactly what sort of building are we looking at in “The Marriage of the Virgin”? The answer is to be found in Paul’s Areopagus sermon, as recounted in Acts 17:22–31 (and the subject of Raphael’s aforementioned painting of 1515). In it, he makes reference to a most elusive place of worship, the altar to the “Unknown Deity.” Paul emphasizes to the Athenians that Jesus was no “new” god, but rather the god the Greeks already worshipped as the Unknown Deity. According to the Church Fathers, the corollary of this is that Jesus was also the God that the Jews had been worshipping all along, albeit blindly and unknowingly. Greek ignorance of the Unknown Deity is the simple result of the eyes of the pagans having not yet been opened. Jewish ignorance of Jesus, by way of contrast, is due to their obstinate and deliberate self-blinding. The Jews, it was thought, were vouchsafed the truth from their earliest antiquity, but stubbornly refused to recognize it.

The Unknown Deity is implicit in the Temple and requires no visual representation—neither in the form of pagan statues nor Jewish devotional objects—real or imagined. The Unknown Deity has always been there, yet is always nascent, always to come, as represented in the very theme of the marriage of the Virgin.

The empty space is itself laden with theological significance. Raphael’s tempietto—with its vacant interior and the view through its empty space of the infinitely receding horizon—is the Temple of the Unknown Deity, the god who is to come. It is a classical space purged both of any distinctive Jewish and pagan elements, a symbol of unperfected pre-Christianity, which is in the process of being consecrated by the marriage that is occurring in the foreground. In “The Marriage of The Virgin,” Judaism per se seems to be entirely glossed over in favor of a general “antiquity.”

Or is it? There is one inescapable element in the composition that disrupts Raphael’s cool classical, iconography-free composition, and thus, the perhaps-too-tidy contention that the building represents the Temple of the Unknown Deity. The building depicted by Raphael is indisputably the Jewish Temple, even if in a classicizing architectural style and even if devoid of all the Temple’s traditional and historical accoutrements. I say “indisputably” for two reasons: according to the texts, the episode of the marriage of the Virgin occurs within the Temple precincts, and the structure depicted is clearly based upon the Dome of the Rock, a building that—as we’ve seen time and again—bears an entire constellation of iconographic associations with the Jewish Temple.

So, Raphael’s tempietto is the Jewish Temple, after all, but shorn of its recognizable features. This is because it is not the historical Jewish Temple, nor some pale foreshadowing of the Church. It is, rather, a Jewish Temple that brings an indictment against the Jews for not seeing what was, in fact, there all along—that the deity they worshipped there with such devotion is none other than Jesus. The inherency of Jesus in the Temple is symbolized by what is now inherent in the marriage before us, ready to burst forth and blossom, from among their own tribes, like Joseph’s budding rod.

It was long predicted that the “rod of Jesse” would flower (Isaiah 11:1-2). Why did the obdurate Jews fail to see it? Raphael answers: They were distracted from the way, the truth and the light, by the complexity of the rites and rituals with which they furnished their Temple. Here, the artist has clarified, purified, simplified the space for us, so that we can focus on what is truly important: the Savior and Son of God who is to come, the Unknown Deity emerging from the apparently empty space, the void at the center of the Temple, into full, humanized reality through the union of this holy couple.

I can’t help but see similarities and differences in the historical imagination and polemic that imbues these Renaissance depictions of the Jews, on the one hand, and that photomontage I saw in Jerusalem on the other. While the Romans erased the actual Jewish Temple in the year 70 CE, the Renaissance Christian paintings and the photomontage of my Jewish hosts each employ a different method to “disappear” the building we see before our eyes, the Dome of the Rock, for centuries considered the “authentic” avatar of the destroyed Temple.

Where Campin’s and Raphael’s paintings colonize, usurp, and transform the meaning of the Jewish Temple while simultaneously retaining the form of the Dome of the Rock as a marker and reminder of the fact that it was a Jewish Temple, the Jerusalem photomontage literally cuts out the Dome of the Rock and replaces it with an equally literal rendition of the Second Temple. The difference, in other words, is between the “merely” theological supersession of Judaism versus the literal erasure of Islam’s holy site.

The physical destruction of a Muslim shrine that has resided on that site for over a thousand years would be an act of physical provocation and invite violent reaction. The paintings we have been examining are not innocent either. They are the visual record of a theology that had real and devastating consequences in the lives of actual Jews, not just in antiquity and in the Middle Ages, but beyond. It is true that the Renaissance was, as Burkhardt described it, the era of “the discovery of the World and of Man” with all the progress that implies. At the same time, even the humanistic Renaissance—still being a Christian Renaissance, after all—could not purge itself of supersessionist theology. The nullification and erasure of Judaism, and the consequent conception of Jewish inferiority incorporated into that theology have, then and since, leapt from the page (and from the canvas) into the lived experience of Jews—with often terrible and disastrous consequences.