How many great Jewish books have owed their survival to the generosity—and the acquisitiveness—of Gentiles? At first glance, the question may seem counterintuitive, if not impertinent. Even leaving aside the two infamous burnings of the Talmud (in 1242 and 1554), who can count the innumerable acts of wanton destruction of Jewish books by Gentiles through the centuries? And what of the multitudes of manuscripts appropriated or seized in the Middle Ages by European nobility and Church officials of all ranks and later secreted away in palaces, monasteries, and cathedrals, there to be mainly forgotten or rendered unreadable by insects, moisture, decay, and the acids of time?

And yet, history, even Jewish history, has its ironies. For one thing, at certain times and in certain places Gentile owners related to their assiduously collected Jewish books out of motives that may have been complicated but were also positive and protective. For another thing, by the 18th and 19th centuries the progressive nationalization of once great private institutions, accompanied by the increasing secularization of society, saw the transfer of many such private collections to newly established national and university libraries. In a flukish but fortunate end to an essentially tragic story, volumes that had managed to survive finally became accessible again to a reading public that also happened to include Jews.

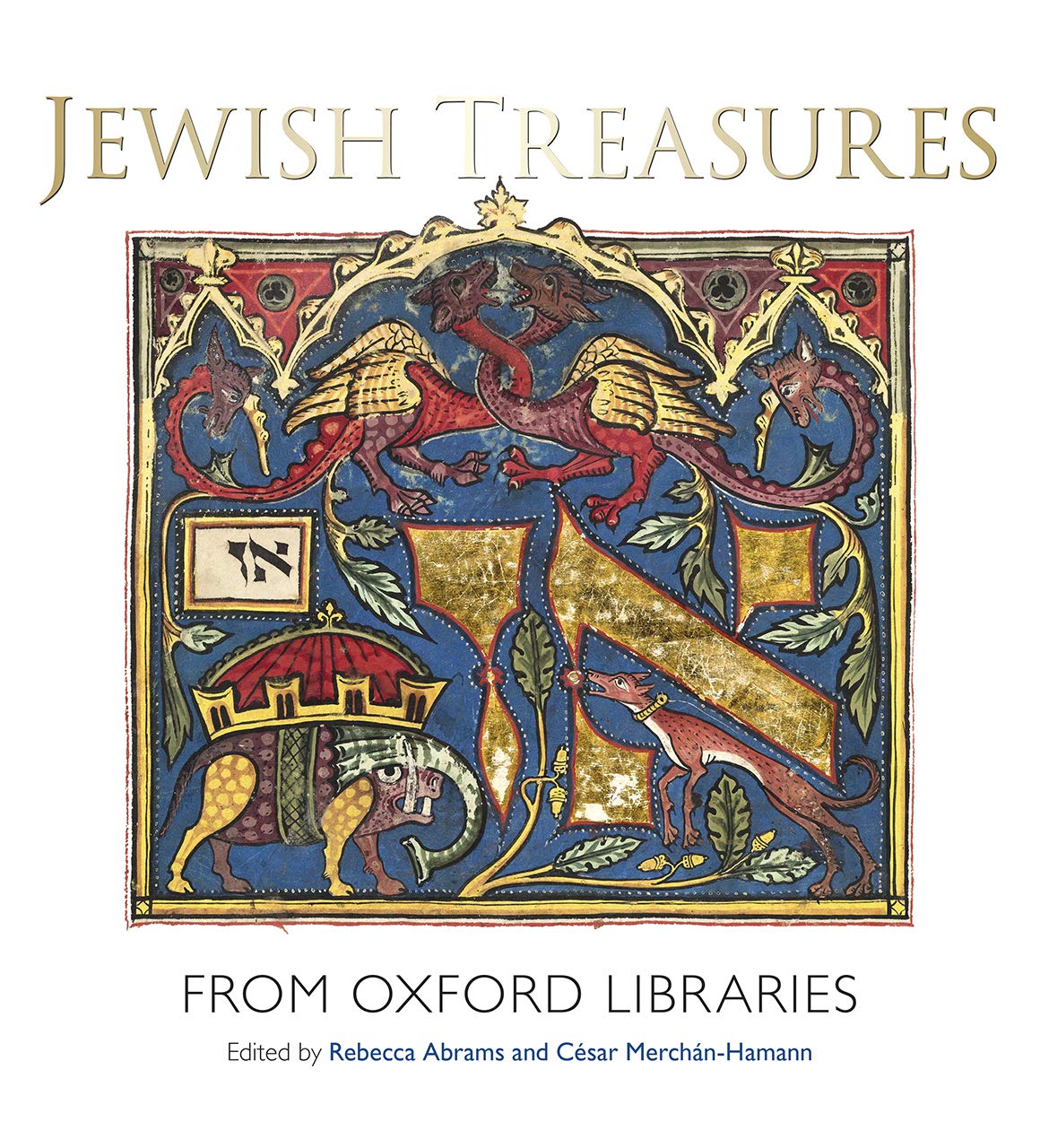

Jewish Treasures from Oxford Libraries, a vivid, lavishly produced, and fascinating new book, testifies to this latter development and its abundant fruits.

Today, one of the greatest collections of Jewish books in the world happens to reside in the Bodleian Library, the main research library of the University of Oxford. Although the library’s two largest bequests of Hebrew books came from Jewish collectors, many of the most precious Hebrew manuscripts were donated or sold to the Bodleian by Christian collectors. Their names—Pococke, Kennicott, Laud, Huntington—have long been immortalized by attachment to their bequests.

But these still do not make up the sum and substance of the Bodleian’s holdings in Hebraica and Judaica. The library also owns a very important collection of texts from the Cairo Genizah (not to be confused with the more abundant harvest from that famed Egyptian depository that would later be brought by Solomon Schechter to the University of Cambridge). And then there are the smaller collections, many of unknown provenance, in the libraries of Oxford’s several constituent colleges: Merton, Corpus Christi, Lincoln, Christchurch, Magdalen, and others.

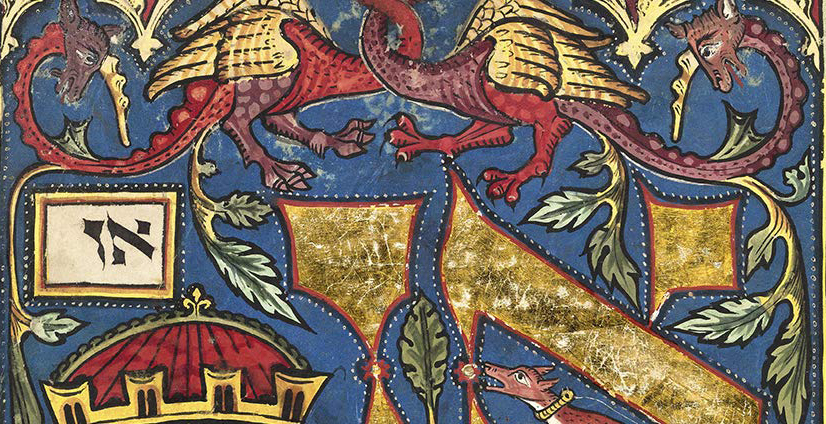

Sumptuously presented examples of these various holdings, interleaved with expert introductions, aesthetic and historical evaluations of individual items, and copious annotations, await the reader of Jewish Treasures from Oxford Libraries. The whole has been meticulously co-edited by Rebecca Abrams (the author of, among other books, The Jewish Journey: 4000 Years in 22 Objects) and César Merchán-Hamann (the Bodleian’s curator of Hebrew and Judaica), who has contributed the volume’s general introduction. In a preface, Martin J. Gross, an American Jewish philanthropist and book lover whose family foundation has generously supported this great project, dwells on the psychology of the collecting impulse and the lasting benefaction of collections like the Bodleian’s to the documenting and preservation of historical knowledge. The entire volume, a triumph of bookmaking, is spectacularly illustrated, with 140 full-color plates that look as if they’re about to jump off the page and meet the reader face-to-face. (Unfortunately, the book’s photographer and designer go unmentioned.)

In the most fascinating feature of Jewish Treasures—a feature never before attempted in a comparable volume about a collection of Jewish books—each of the work’s seven central chapters relates the story of one of the Bodleian’s Hebrew collections and, even more interestingly, the career of the collector behind it.

The Bodleian Library was founded in 1598 by Thomas Bodley, a diplomat in the king’s service, later a member of Parliament, and a staunch Protestant. Bodley also subscribed to a movement among learned Christians that, first emerging in the Middle Ages, gained special force during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. These Christian Hebraists, as they came to be known, had increasingly recognized the importance of learning Hebrew and studying classical Jewish texts—the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, and especially Kabbalah—for a correct understanding of the Old Testament as background to the rise of Christianity.

The Christian Hebraists were not Judeophiles; they were less interested in Jews than in their holy scriptures and books. Out of this predilection sprang Bodley’s specific interest in adding such works to the new library’s collection. In 1601, just three years after its founding, the Bodleian received its first Hebrew gift, a 13th-century copy of the book of Genesis, followed within the same year by another of the book of Ezekiel, both accompanied by an interlinear Latin translation. These were among other such bilingual texts that the library would acquire, each of them testifying to a remarkable moment in the High Middle Ages of Jewish-Christian scholarly collaboration. Their early arrival in the Bodleian seems almost like a portent of the library’s future importance for the burgeoning of the field of Jewish studies in the modern era.

Three more collections, much more varied than Bodley’s, were added over the course of the 17th century. The first was from William Laud, archbishop of Canterbury, chancellor of the university, and one of the most powerful—and disagreeable—personalities of his time, whose many imbroglios eventually led to his execution for high treason.

When not engaged in political maneuvering, Laud was a passionate promoter of scholarship at Oxford, particularly the study of Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic, and an avid collector of manuscripts with the specific purpose of donating them to the Bodleian. As a collector of Hebraica in particular, Laud grew increasingly focused on Hebrew texts from northern Italy in the early modern period and then, in a fascinating evolution for an archbishop of Canterbury, on medieval Ashkenazi works.

Edward Pococke (1604-1691) was simultaneously Laudian Professor of Arabic (in a chair established by Laud) and Regius Professor of Hebrew. Essentially, Pococke’s was an Oxford don’s working library, and its enormous breadth—in addition to Hebrew, it boasted texts in Samaritan, Ethiopic, Armenian, Arabic, Persian, and Syriac—reflected the incredible diversity of a great scholar’s intellectual interests in virtually every field of knowledge known to mankind at the time. Included in this collection were parts of Maimonides’ personal copy of his Commentary on the Mishnah, composed in Judeo-Arabic with, in the margins, the author’s own hand-written revisions of the text.

Next, the largest major 17th-century collection of Judaica, some 200 manuscripts in all, came from Robert Huntington (1637-1701), a student of Pococke’s who became a chaplain to the English Levant Company in Aleppo and Istanbul as well as a book-buying agent in the “Oriental” languages on behalf of his former teacher and other clients. In the course of his purchases, Huntington amassed a huge Hebraica collection of his own, deriving mainly from medieval Spain and the Near East and encompassing virtually every genre of classical Hebrew literature.

Chronologically fourth in Jewish Treasures from Oxford Libraries comes the 18th-century collection built by Benjamin Kennicott (1718-1783), one of the foremost biblical scholars of the age. Kennicott’s life’s work was a massive project to record and collate every textual variant he was able to find in some 600 manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible and more than 50 early printed editions. In the course of pursuing this project, Kennicott acquired ten biblical manuscripts, which upon his death he left to a small private library later absorbed by the Bodleian.

While Kennicott’s is the smallest of Bodleian’s Hebrew collections, it contains its most valuable and beautiful manuscript: an extraordinary illustrated and decorated 15th-century Bible from Spain known simply as “The Kennicott Bible.” Theodor Dunkelgrün’s treatment of Kennicott, perhaps the stand-out chapter in Jewish Treasures, masterfully charts the intricacies of his subject’s personal and scholarly career, along the way offering vivid portraits of each of the ten biblical manuscripts in this collection.

The last three collectors treated in Jewish Treasures differ from the others in two respects: none of them had any connection to Oxford, and none of the collections was donated. Instead, all were bought by the library on the market.

The first of the three men, Matteo Luigi Canonici, was a colorful 18th-century Italian Jesuit and dealer in books and art. His credo, he said, was to buy “beautiful items,” but only “if they [were] real bargains” and only so long as his customers were “always satisfied” and his own “honorability remain[ed] impeccable.” The Bodleian purchased more than 2,000 manuscripts from Canonici’s personal collection, including 118 Hebrew manuscripts of all types. It was the largest purchase the library ever made.

This brings us to the final two collectors, David Oppenheim (1664-1736) and Heimann Joseph Michael (1792-1846), who were Jews.

Oppenheim, one of the most distinguished rabbinic figures of his age, was the chief rabbi, successively, of Moravia, Bavaria, and Prague and arguably the greatest bibliophile in Jewish book history. In an inventory of his library, Oppenheim stated his ambition to collect every Jewish book that existed, whether in print or in manuscript. By the time of his death, he owned 1,000 manuscripts and more than 4,500 printed volumes, a number of which are the only extant copies today. As Joshua Teplitzky explains in his excellent chapter in Jewish Treasures, Oppenheim’s interest was not merely that of a bibliophile; his books constituted the working library for his day job as a rabbi-cum-scholar. As a complete bookman, he also saw to the publication of manuscripts that had not yet appeared in print. His collection makes up the bulk of the Bodleian’s Hebraica.

Roughly a century after Oppenheim, Heimann Joseph Michael, a businessman in Hamburg and a lay scholar with a special interest in liturgical poetry, amassed an even larger collection of printed books as well as hundreds of manuscripts. As a childhood classmate and lifelong friend of Leopold Zunz, the leading figure in the emerging “Science of Judaism” (Wissenschaft des Judentums), Michael built his collection intentionally to serve the interests of that budding academic enterprise. His purpose, as Saverio Campanini writes in his fine chapter, was “to provoke and to satisfy” the critical questions raised and discussed by modern Jewish scholars.

As even these brief sketches may suggest, the figures represented in Jewish Treasures in Oxford Libraries were more than mere amassers of books. Each built a library that reflected his personal interests. In doing so, however, they not only discovered but also brought together books that on their own, as it were, would never have encountered each other. In many cases, moreover, just by the act of acquiring them, the collectors also saved numerous manuscripts and books from vanishing.

And herein lies the rarely acknowledged and even more rarely appreciated importance of collectors—great collectors, that is, with a vision for their holdings. Libraries and librarians catalogue and preserve books; only rarely do they have the time, and even less often the resources, to build great collections, let alone to define new fields of inquiry by acquiring materials in them. Scholars, for their part, use the material they find in libraries and archives, but only seldom and fortuitously do they happen to acquire a previously unknown book, let alone a group of books or artifacts that can help constitute a mini-field.

Collectors are different. Because they have abundant resources, or a highly developed talent for finagling, along with a compulsive, sometimes monomaniacal determination to acquire and own objects, they are able to unearth things discoverable by no one else and to gather substantial amounts of material on subjects or fields that no one has previously managed to bring together. Underneath a great collection of books lie webs of subterranean connections linking individual volumes to each other in small but revealing ways.

The same can be observed, on a larger scale, in the case of seemingly disparate collections that reside in a single library like the Bodleian. Thus, a number of the collectors represented on the Bodleian’s shelves happened independently to acquire manuscripts either written by Maimonides himself or owned by him; now they sit next to each other on adjacent shelves, together offering a proximity to the accumulated erudition and groundbreaking originality of the great medieval Jewish sage available nowhere else in the world. These networks of latent messages lay out a groundwork in which scholars even today are still searching for buried treasures.

No doubt, both David Oppenheim and Heimann Joseph Michael wished their collections to remain intact, and both certainly intended them to remain in the hands of German Jewish owners, either private persons or institutions. They never imagined that their collections would end up at Oxford. Yet because of the twists of fate, financial vagaries affecting the individuals involved, and the shifting winds of both European and Jewish culture at the time of the collections’ dissolution, neither was able to find a Jewish purchaser in Germany. Oppenheim’s collection was about to be put up for auction in 1826 when the Bodleian acquired it at a bargain-basement sum.

At least the Bodleian’s purchase did enable the Oppenheim collection to remain intact. Less happy was the fate of Michael’s. No German institution, public or private, was prepared to purchase its entirety. The printed books, put up for auction, were bought by a private book dealer who then re-sold them, partly to the British Museum and partly to the Prussian State Library in Berlin. As for the manuscripts, efforts to interest Jewish buyers in Germany proved unsuccessful; once again, and again at a bargain price, the Bodleian came to the rescue.

Leopold Zunz, lamenting the loss to the Jewish community of the library of his childhood friend Michael, placed it among “the few memorials that Jews had established and that Christians preserve.” The same elegy applies equally to the Oppenheim collection. Still, thanks to their current owners, both collections have indeed been preserved and survive today. Even if parts of them may reside in separate institutions, their locations are known. Moreover, in a way that Zunz and other Jewish scholars in his time could never have imagined possible, all of their contents are accessible to Jewish and non-Jewish scholars alike.

Would that one could say the same about more recent great collections of Jewish books, virtually none of which has survived intact. Over the last several decades, collections of Hebraica too numerous to list have been broken up and sold at auction with their contents going off in every direction and sometimes vanishing altogether from sight.

The most egregious example is the case of the Valmadonna Trust, the biggest collection of Hebrew printed books and manuscripts ever amassed. After the death in 2016 of its collector and owner Jack Lunzer, the Lunzer family made a series of attempts to find a purchaser, anywhere in the world, for the collection as a whole. When this failed, the choicest manuscripts were auctioned off to multiple diverse buyers while the printed books were later sold to the National Library of Israel, which then re-sold those particular volumes for which the library held duplicates, scattering them to the winds.

Who today will rescue the great Jewish book collections that still survive? Where today is our Bodleian?

More about: Arts & Culture, Books, Oxford