To mark the close of 2020, we asked several of our writers to name the best three books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. We have encouraged them to pick two recent books, and one older one. The first five of their answers appeared yesterday; the next six appear below in alphabetical order. The rest will appear tomorrow. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2020. Classic books are listed by their original publication dates.)

Haviv Rettig Gur

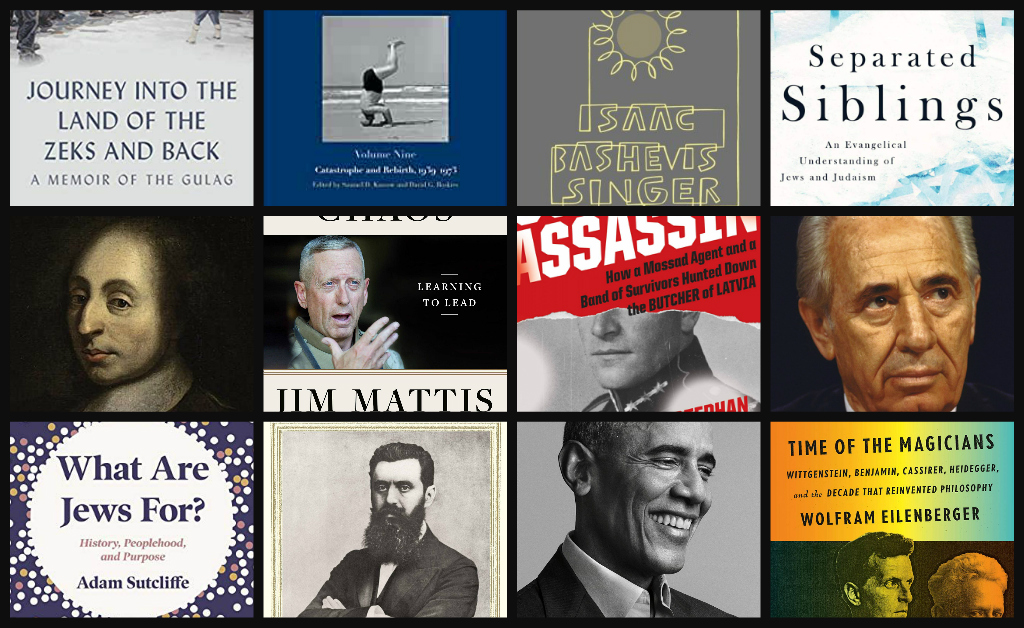

In What Are Jews for? History, Peoplehood, and Purpose (Princeton, 376pp, $35), Adam Sutcliffe, a history professor at King’s College London, has penned a dense but enlightening history of the idea of Jewish purpose, from its primordial roots in the biblical idea of consecration to a protector God into part of the intellectual bedrock of Western civilization. It is nigh impossible for modern Westerners to grapple with notions of peoplehood, of the meaning of history, and of the tensions between particularist and universalist ethics without appealing, sometimes unknowingly, to the Jewish discourse around purpose and chosenness. There is much here that was new to this non-academic reader. The book sometimes tilts to the left, including in its final section, where it identifies certain narrow ideas about Jewish purpose with present-day Israelis and takes them to task for it. But these moments are never overly cartoonish or wanton. In the end, it is a defense of the Jewish idea of purpose as a deep and broad and complex notion, and as a key source that later European and modern cultures have drawn on to construct their own identities and sense of self.

Derek Penslar’s Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader (Yale, 256pp., $26) is a short, pleasant, illuminating, and unvarnished biography of a man we all already know. Its great strength, it seems to me, lies in Penslar’s synthesis of two usually opposed threads in Herzl biographies: the reverential and the psychodramatic. Zionists see in Herzl a man of astounding insight, vision, and organizational ability without whom the Jewish state might have remained a dream. More recent and more fashionable deconstructors of the Herzl myth find their happiness in carefully mapping out his tormented emotional world and suggesting that mental imbalance, not genius or vision, drove his activism. The Harvard historian Penslar’s valuable insight lies in the suggestion that the two are inextricably linked, that the leader was forged in the fires of his inner struggles. It was those struggles that drove his hunger for meaning, granted him his astonishing drive and resilience in the face of repeated failure, and produced the overflowing charisma and conviction that alone could have forged a public persona able to coalesce the nascent Zionist movement’s disparate and multilingual strands into a focused, organized force in the world. A happier man, Penslar suggests, could not have done those things. A rewarding read.

Moshe Koppel’s Judaism Straight Up: Why Real Religion Endures (Maggid, 218pp., $24.95) is a punchy polemic fired across the battlements of the culture war. But it goes deeper than most culture-war books. It is a quintessentially Israeli, occasionally snarky, and unabashedly opinionated appeal for authenticity and humility. Its core argument is a meditation on the value of “evolved” traditional societies in the face of the perils of progressive social engineering. But it criticizes not only liberal attempts to deconstruct or reconstruct traditional social mores, institutions, and ideas, but also conservative (lower-case c) and orthodox (both upper-case and lower-case o) counter-responses that suffer from the same artificiality. Worthwhile and accessible.

Ed Husain

The title of Barack Obama’s book A Promised Land (Crown, 768pp., $45) rests on a Jewish concept—God’s promise of the Holy Land to the Jewish people in the Bible and the Quran—yet Obama was unable to understand the deep history and anxieties of the Jewish people. His thinking remained tied to the ideas of far-left Palestinian academics and activists from his younger days. The book is a political masterpiece on how, in Syria and elsewhere, Obama’s pontificating and indecision is also a decision, inaction is also action, and why leaders should not be held hostage by their idealist advisors. As a new U.S. administration prepares to govern, understanding what President Obama did not, and answering the challenge posed by Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammad bin Zayed of the United Arab Emirates to Obama in the midst of revolutionary turmoil, should guide U.S. foreign policy. “It shows,” said the crown prince, “that the United States is not a partner we can rely on in the long term.” That “calm and cold” warning to Obama is what the Biden-Harris administration should heed. A Promised Land is vital reading to remind us why the West should stand by its allies, and not appease its enemies.

Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade That Reinvented Philosophy by the German thinker Wolfram Eilenberger has been causing a storm in Germany, for this book brings to life a decade-long miraculous burst of intellectual creativity from 1919 when German philosophers were asking the deepest questions about life and existence. Three of the four philosophers were of Jewish ancestry—Walter Benjamin, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Ernst Cassirer—and the fourth loved the great Hannah Arendt, also Jewish, but then became a Nazi and spent a life never explaining his Nazism: Martin Heidegger. These titans sought to answer “What are we?” but all around them white, Aryan supremacy had its own ugly political answers. If Nazism and fascism emerged as the most idealistic questions were being asked after the Great War, what of our times when we have no memory of war and no longer ask existential questions? Where will our political and identity divisions take us?

I have also been reading Voltaire’s Candide (1795, 280pp., $21). The author was no friend of Jews or Muslims, but he learned much from John Locke and Isaac Newton and then helped change France. Locke and Voltaire’s writings on tolerance and free inquiry bequeathed the Enlightenment and the modern world to us. They uprooted dogma and set us free as citizens. Today, we take liberty and citizenship, nation state and the rule of law for granted. By reading Voltaire, we are reminded of the darkness from which Europe emerged and with it, the United States. “If you want the present to be different from the past, study the past,” warned Spinoza. Civilization is fragile.

Martin Kramer

Just when we think we know all there is to know about the modern history of Zionism and Israel, a new book deflates our confidence. Here are two new ones that did just that in 2020, and a classic that did that long ago.

Shimon Peres remains one of the great enigmas of Israel’s history. He was a high-flying statesman of international caliber who kept falling to earth. Israelis saw in him the glimmer of a visionary à la Herzl, so they kept him in public life. But this indulgence came with a condition: he would always be “number two” to someone else, and he would have to propitiate this “number one” to get his work done.

Avi Gil, trained as a diplomat, ended up as an adviser to Peres for 28 years. His Shimon Peres: An Insider’s Account of the Man and the Struggle for a New Middle East (I.B. Tauris, 264pp., $26.95) caused a stir when it appeared in Hebrew in 2018. Other advisers had written reverential memoirs about their political bosses. Gil, by contrast, is admiring of Peres’s strengths, but unsparing when it comes to his faults, above all his preening ego. It wasn’t always clear what drove him: vision or vanity.

Whatever one thinks of the Oslo Accords (Gil thinks more of them than you probably do), they represented a double triumph for Peres. To maneuver Yasir Arafat into an agreement, he first had to outmaneuver his nemesis, Yitzḥak Rabin. The backstory of how Oslo got made isn’t pretty, replete as it is with lies and betrayals. But it’s also riveting.

This year was the 60th anniversary of Israel’s 1960 capture of Adolf Eichmann. (I wrote about an aspect of it for Mosaic back in June.) But that wasn’t the end of Israel’s hunt for Nazis. In 1965, Herbert Cukurs, a Latvian collaborator involved in the murder of 30,000 Jews, turned up dead in Uruguay. A statement attached to his body, stuffed in a trunk, denounced him for his crimes against Jews. Years later, the Israeli who lured him to his death revealed that it had been a Mossad assassination.

The journalist Stephan Talty has retold the story with verve in The Good Assassin: How a Mossad Agent and a Band of Survivors Hunted Down the Butcher of Latvia (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 320pp., $28). The chief Israeli agent, Jacob (“Mio”) Medad, whose parents perished in the camps, first revealed the details in a memoir published over twenty years ago. But Talty greatly enriches the context of the Mossad operation. We learn in depth about the Holocaust in Latvia, the inspiring life story of a key witness, and the strange personality of Cukurs. A famed long-distance aviator before the war, he descended into unspeakable cruelty. Suffice it to say, he was no desk murderer. So he got what Talty calls “a certain kind of killing. . . . [T]here would be no trial, no lawyers or judges, no legal niceties, no essays by Hannah Arendt in The New Yorker.” The deception involved in the operation was ingenious, but the denouement wasn’t very tidy. No more spoilers.

And something classic? The Balfour Declaration by Leonard Stein appeared in 1961. (Simon and Schuster published the American edition.) I still find its 700 pages invaluable, despite the appearance of later studies based on archives that weren’t open to Stein in the 1950s.

This was meticulous history, written by an amateur. Stein, a graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, and a veteran of World War I service in Palestine, became a tax lawyer and a Zionist activist. Yet he deftly uncovered and untangled the interests that converged in the declaration. His main discovery, obvious today but not realized 60 years ago: British interests, not pro-Jewish sentiment, underpinned the declaration. Indeed, some of the Balfour Declaration’s chief British proponents were (shall we say?) less than enamored of Jews.

Stein died in 1973, at the age of eighty-five. The Balfour Declaration is a sturdy monument.

Robert Nicholson

Jim Mattis and Bing West, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead (Random House, 2019, 320pp., $28). This gritty and insightful reflection on leadership, written by the U.S. Marine Corps’ best warrior-scholar, builds on the author’s real-life experience amid the complexities of 21st-century combat to survey America’s enduring but evolving role in the world.

John E. Phelan, Jr., Separated Siblings: An Evangelical Understanding of Jews and Judaism (Eerdman, 360 pp., $25). Recognizing that many Christians feel a strong but superficial affinity with Jews based on scripture and the story of modern Israel, John E. Phelan, Jr. takes his readers on a sympathetic, three-dimensional journey through modern Judaism, Jewish identity, and the Jewish state.

Blaise Pascal, Pensees (1670, 368pp., $13). Fragmentary and cryptic by turns, this rambling collection of meditations from the French mathematician Pascal remains one of the most incisive commentaries on the paradoxes of human existence.

Ruth Wisse

This year it was especially difficult to choose from among a number of splendid books. Limited to two, I’ve selected the weightiest—heavy and daunting tomes that may therefore need extra encouragement to pick up and read.

Julius Margolin wrote his memoir, Journey into the Land of the Zeks and Back in 1947 (Oxford, 648pp., $39.95), when he returned to Mandate Palestine, having left there in 1939 for what was intended to be a short visit back to his native Poland. Trapped by the outbreak of World War II between the German and Soviet invaders of Poland, he was arrested by the latter in the summer of 1940 and spent the next five years in the concentration and labor camps of the Gulag, philosophically alert to the social experiment he was being exposed to while physically subject to its inhuman conditions.

Whereas survivors of the Shoah were immediately encouraged to record their experiences, those like Margolin who survived the Soviet death camps were kept by admirers of the socialist paradise from letting the world know about what it was in fact. It has taken this long for Margolin’s remarkable work to appear in English, finely translated by Russian scholar Stefani Hoffman, and though some of what he describes is no longer revelatory, his serene intelligence, acute perception, and bemused self-awareness make it worth knowing the writer as well as the political reality he describes. The controlled power of his writing guides us through the 587 pages of his dreadful account. (A review is forthcoming in Mosaic—eds.)

The ninth and penultimate volume in the Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, subtitled Catastrophe and Rebirth, 1939-1973 (Yale, 1,088pp., $175) covers the most consequential period in Jewish history since the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE. I was skeptical when I first heard about the aggrandized ambition of this project, so it is good to see it prove valuable.

The warning never to judge a book by its cover does not apply here. The jacket photograph of David Ben-Gurion standing on his head at Herzliya Beach in 1957 captures the spirit of this book that brings an unusual flair to anthologizing, not just for the sake of novelty but to demonstrate, like this photograph, the unexpected freshness and vitality of the Jewish people during these death-defying years. Entries limited to 1,000 words allow for breadth of coverage more than full treatment of any author or theme: with examples drawn from every medium and area of Jewish life, this is the composite story of how a creative people laughs, sings, thinks, acts, and prevails against history’s greatest odds.

Readers of this tome will see that it was not nepotism that makes me select a work co-edited by Samuel D. Kassow and my brother David G. Roskies.

And a favored work from past reading? Every day something else occurs to me, and this just happens to be what I looked up yesterday in preparing for Hanukkah. Moses Hess published Rome and Jerusalem (263pp.) in 1862 and parts of it remain unsurpassed in its understanding of Jewish nationalism and the need for Jewish self-emancipation and self-rule. The “Rome” of this title is not the ancient nemesis of the Jews in 70 CE: it stands for the Italian Risorgimento as a model of national unification for what came to be known as Zionism three decades later.

That Hess began as a devotee of Karl Marx helped him understand the dangers of many historical movements and ideas then taking hold in Europe. Hess’s counteracting concept of nationhood begins not in social theory but in the family and builds outward from maternal affection to a capacity for creative coexistence. He writes this thesis in the form of letters to a woman he is trying to comfort in her bereavement, casting his call for the “revival of Israel” as the modern version of Isaiah’s cry, “Comfort ye, my people!” And so, to this day, it does.

David Wolpe

Jonathan Sacks, Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times (Basic, 384pp., $30). Among the saddest losses of this sad year was the passing of two g’dolim, two giants of Torah, the great talmudic scholar and expositor Adin Steinsaltz, and Jonathan Sacks. Rabbi Sacks’s last book epitomizes his virtues—anecdotal but not superficial, wide-ranging but always pertinent, erudite but not stodgy. Morality is a summation of modern moral perplexities and a clear, persuasive voice from our tradition shining a way forward. (An excerpt of the book is available here—eds.)

Moshe Halbertal, Nahmanides: Law and Mysticism (Yale, 464pp. $55). One of the great minds and spirits of our people, commentator, moralist, kabbalist, philosopher, polemicist, and more, Naḥmanides is too little-known outside of the source-studying Jewish community. Moshe Halbertal’s learned, lucid, and wonderfully far-reaching study should be pressed eagerly into the hands of all who want to know a giant of our people in his great complexity.

Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Collected Stories (1983, 624pp., $13.80). The great Canadian novelist Robertson Davies said what a writer needed was “the wand of the enchanter.” No one wielded a more potent wand than I.B. Singer. Rereading his short stories has reminded me of the puckish charm, the sly insight, the love for humanity that his wand conjured in story after story. Here are the openings to two stories, really at random. If you don’t want to hear how it ends, lay down your lorgnettes, for your heart is a peach pit.

Herman Gombiner opened an eye. This was the way he woke up each morning—gradually, first with one eye, then the other.

And:

The doctors all agreed that Henia Dvosha suffered from nerves, not heart disease, but her mother, Tzeitel, the wife of Selig the tailor, confided to my mother that Henia Dvosha was making herself die because she wanted her husband, Issur Godel, to marry her sister Dunia.

More about: Arts & Culture, Best Books of the Year, History & Ideas