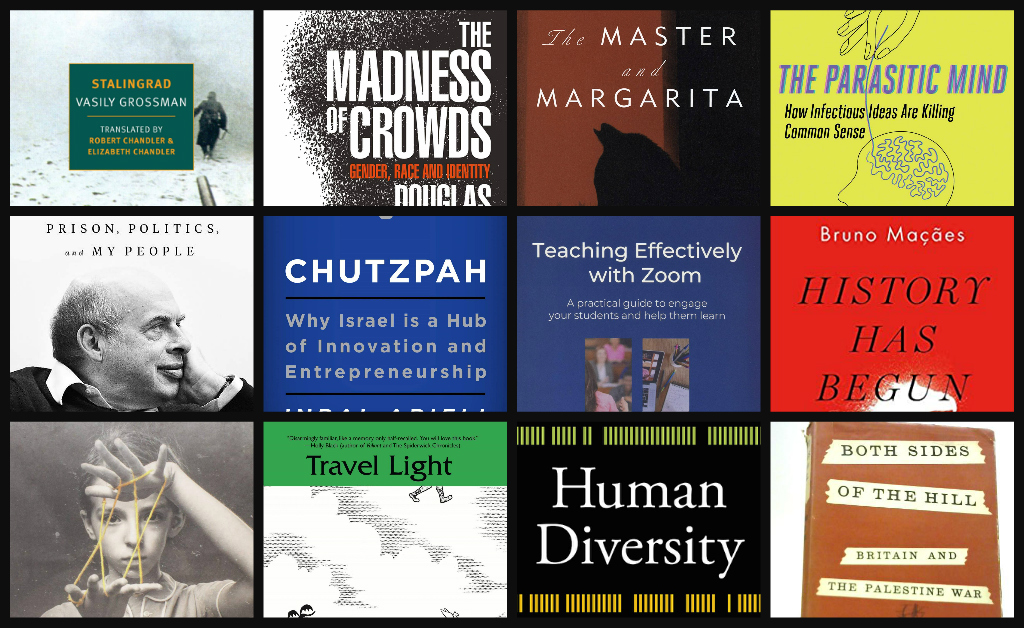

To mark the close of 2020, we asked several of our writers to name the best three books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. We have encouraged them to pick two recent books, and one older one. The first eleven of their answers appeared yesterday and the day before; five more appear below in alphabetical order. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2020. Classic books are listed by their original publication dates.)

Gary Saul Morson

Vasily Grossman, Stalingrad (NYRB Classics, 2019, 1,088pp., $27.95). Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, which some consider the most profound novel of the 20th century, was actually the sequel to an earlier narrative, Stalingrad. The new and brilliantly edited English version includes passages Grossman was forced to omit, marks changes made from edition to edition as the Communist-party line changed, and indicates which words were written into the text over Grossman’s objections. It therefore offers a short course on what even a successful Soviet writer had to endure. As it narrates the thrilling battle of Stalingrad, which finally put the Germans on the defensive, the book manages to suggest how similar were Bolshevik and Nazi values. Especially interesting is Grossman’s discussion of the Soviet regime’s doctrine of “two truths”: events that actually happen are less real than those which, even if they don’t, Marxist theory identifies as the essence of things. Soviet writers were expected to represent this second truth. Fighting for the first, Grossman’s novel waged its own Stalingrad against overwhelming forces.

Douglas Murray’s The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity (Bloomsbury, 2019, 288pp., $20) manages to say something unexpected about identity politics. As a gay man familiar with the struggle for gay rights, Murray demonstrates the rare ability to see identity movements from both within and without. He saves his key conclusion for the end so we already have evidence to support it: “nothing about the intersectional social-justice movement suggests that it is really interested in solving any of the problems it claims to be interested in.” Is Murray right?

A classic reread: if Grossman’s Life and Fate is not Russia’s greatest modern novel, then Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (1967, 384pp., $16)—in the brilliant translation of Katherine O’Connor and Diana Burgin—surely is. I have never met a person who didn’t like it. Profound, funny, wise, entrancing, and endlessly inventive, it tells two stories. One concerns the devil’s visit to officially atheist Stalinist Russia and the surprising tricks he plays on complacent Bolsheviks convinced their “scientific” philosophy has explained everything. In a novel within the novel, written by the book’s hero and confirmed by the devil, we learn the true story of what happened with Jesus (called Yeshua, so we see him in his Hebrew context) and Pontius Pilate. Much as the fantastic invades Soviet Russia, so the Jesus story is told realistically—not to debunk it but, on the contrary, to reveal its sacred wisdom all the better.

Yehoshua Pfeffer

Gad Saad, The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense, (Regnery, $28.99). Saad was born in Beirut to a traditional Jewish family, experiencing a fair amount of discrimination and persecution before miraculously escaping (his words) Lebanon in 1975. The book includes many anecdotes and some wicked sarcasm; it is also so well-written, and so free of academic obfuscations, that I consumed it in just a few days.

The Parasitic Mind is a worthy addition to the growing body of literature critiquing “The Great Awokening” of our times. While by no means the first to rally against the injustices of political correctness and the enforcement agencies of intellectual tyranny, against the “ethos of feelings” that has replaced the “ethos of truth and wisdom,” and against the politics of tribalism that has superseded that of reason, it is certainly one of the more eloquent manifestos I’ve read in favor of a meritocratic, free society that encourages personal responsibility as opposed to victimhood, truth as opposed to its postmodern deconstruction, and (Western) liberty as opposed to (Islamist) tyranny.

But beyond its elegant prose and its convincing—and chilling—depiction of the ailments plaguing our modern era of discontent, certain elements of The Parasitic Mind gave me pause. Saad chides harshly those who identify with his views yet are reluctant to express them for personal reasons. But the biblical prophet Zechariah teaches us that we must love both truth and peace, and, as one ancient rabbinic source points, we must sometimes find a compromise between these inherently contradictory goods. While Saad’s “in your face” approach is at times right and necessary, at others it is not.

Saad also writes that his love of truth and freedom drove him to leave religion: “My inquisitive nature felt stifled by religious dogma. I found no freedom in religious practice.” I find the implicit claim that (Jewish) religion is incompatible with freedom and reason no less of a wakeup call than Saad’s polemic against trendy illiberalism, and it seems his uncompromising individualism, prominent throughout the book, leaves little room for community, for custom, or for God. Thus Saad rejects values that I hold to be no less crucial than those he affirms. This too, left me thinking about the complex relationship between these two sets of values.

Inbal Arieli, Chutzpah: Why Israel Is a Hub of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Harper Business, 2019, 272pp., $29.99). Inbal Arieli is a successful participant in Israel’s start-up sector, having founded a series of programs for innovators and served as the CEO of a successful company. She did not write this book for financial gain, but to offer her insights into the great question of how to give our children the requisite skills to become leaders, entrepreneurs, and innovators. Her answer is that leaders are formed in an environment of “controlled chaos” that breeds mental agility, improvisation, and resilience. She calls the Israeli mindset “chutzpah,” and credits it with Israeli breakthrough achievements as the PillCam, the USB flash drive, the Pentium MMX Chip, and WAZE.

While service in the IDF presents young Israelis with ample opportunity for innovation and improvisation in the face of dynamic threats, Arieli claims that the chutzpah mindset is ingrained in Israelis from early childhood, seeing the gritty environments that toddlers play in, Lag ba-Omer bonfire games, and scouting groups in which counsellors are barely older than the children themselves as breeding grounds for future entrepreneurs.

I found the book valuable not only in its account of Israeli achievement in the high-tech sector, but also in its eloquent and deeply personal depiction of the Israel that Arieli is familiar with. Having lived in Israel myself for close to 30 years, I can say that the description is wonderfully accurate for a particular sector of Israel’s population—specifically the one that is Jewish, secular, mostly Ashkenazi, and Tel Aviv-oriented. Needless to say, it has been many years since this group enjoyed majority status in Israel, and given this fact the question the book raises is: what does the future hold for Israeli enterprise and for the economic future of a country so dependent on its high-tech sector? Hailing as I do from the Israel’s large and rapidly growing ḥaredi community, this question becomes highly personal: does Arieli’s description allow room for ḥaredi participation in Israeli high-tech?

I do not have clear answers to these questions, but reflecting on an additional question might provide some insight, namely: are these qualities specifically Jewish, or are they only Israeli? Though Arieli does not enter into this discussion, I believe many of them are. What, for instance, could be a greater example of chutzpah than Abraham’s demand of God: “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do justice?” (Gen. 18:25). So too, I suspect that the optimism Arieli attributes to Israel culture has its roots in the Jewish tradition. And a sense of optimism about the future of the Jewish state is exactly what this book gave me.

Asael Abelman, Dust and Heaven: A History of the Jewish People. Published in Hebrew toward the end of 2019, and hopefully forthcoming soon in English, Abelman’s one-volume history of the Jews is a truly remarkable achievement. Although the book stretches across millennia and continents, it reads almost like a novel, with our great ancestors serving as its heroes. In Abelman’s history, the true protagonist is the Jewish people itself.

The book’s title is borrowed from a poem by Nathan Alterman, which foresaw that the Jewish people is destined to struggle with a divine figure, just as Jacob wrestled with the angelic being who granted him the name Israel. The struggle itself results in the fusion of Israel with the Divine, “Dust and Heaven,” fulfilling the promises that Abraham was given for his future nation: as the dust of the earth, and as the stars of heaven. Such is our national history: dust and heaven, earth and spirit, nation and religion, fate and destiny.

In a brief prologue Abelman acknowledges four teachers, the last of them being the regular Mosaic contributor Ruth Wisse, who demonstrated to him that teaching was not merely bequeathing knowledge and tools for further study, but instead empowering the student to love learning. This is the spirit of the book. Abelman challenges his readers to think deeply about the ideas latent in Jewish history, peppering his text with a range of opinions among historians and researchers. But he does so with a passion—a passion for the Jews and their remarkable history—that is infectious. The book is worth reading if only for this.

Daniel Polisar

It was easy for me to choose my top recommendation among books published in 2020. Never Alone: Prison, Politics, and My People (PublicAffairs, 480pp., $30), a memoir of Natan Sharansky’s extraordinary life co-authored with Gil Troy, the noted political historian and scholar of Zionism, provides a window into three fascinating worlds in which Sharansky placed leading roles: the Soviet Union as it sought unsuccessfully to squelch the burgeoning movement of Jews seeking to make aliyah, Israeli politics during the turbulent decade beginning in the mid-1990s, and Israeli-Diaspora relations as seen through the lens of the Jewish Agency’s efforts to bridge the gaps. Never Alone is a terrific read throughout and, remarkably, the authors fill the potentially prosaic sections on Israel and the Jewish Agency, which could have been a letdown after the descriptions of Sharansky’s heroism in facing down the KGB, with gripping and inspirational stories that illustrate how a man of principle, character, and wisdom can make a difference in every field of endeavor.

When 2020 began, the odds I would end up recommending a book on online pedagogy as one of my top picks for the year appeared to be virtually nil. Yet thanks to COVID-19, I found myself, like so many of my colleagues, needing to learn overnight how to apply teaching skills developed almost entirely in a classroom setting to the new, Zoom-based format. There are a number of excellent books available on this subject, but I especially liked Dan Levy’s Teaching Effectively with Zoom: A Practical Guide to Engage Your Students and Help Them Learn (self-published, 212pp., $12.99). In addition to combining well-grounded educational principles with very practical advice, it also helps readers take the lessons from online learning and apply them to becoming better teachers in the future when in-person learning again becomes the norm.

For my classic book I chose Michael Oren’s The Origins of the Second Arab-Israel War: Egypt, Israel and the Great Powers, 1952-1956 (224pp.). Though not as well-known as his three subsequent non-fiction best-sellers, this 1992 work bears the hallmarks that have made Oren the most renowned Zionist historian in the English-speaking world: a subject of epic importance, meticulous and balanced research, superb writing, and the ability to weave trenchant analysis into a gripping story. Anyone interested in gaining a better understanding of a conflict that is rightly considered to be Israel’s second war of independence would benefit from—and greatly enjoying reading—Oren’s historical tour de force.

Neil Rogachevsky

In the Times Literary Supplement’s excellent “books of the year” feature this year, the British philosophy professor Raymond Tallis wrote: “Alas, I have not this year read any books published in 2020.” How could one possibly improve on this sincere and constructive statement?

Of course there have been worthy works published this year. I would start with Bruno Maçães’s History Has Begun: The Birth of a New America (Oxford, 248pp., $29), a provocative, political philosophy-informed look at contemporary America. Highlighting its declining religious observance and its loosening ties to the European past, Maçães advances the disquieting but not altogether persuasive thesis that America is just now becoming a mature country that is disengaging itself from the Western civilization from which it emerged. This is a book that must be reckoned with, particularly by defenders of America’s religious heritage.

Next we turn to the latest and potentially final work by Tom Stoppard, perhaps the most distinguished and justly celebrated living playwright. Leopoldstadt (Grove Press, 101pp., $15.99) had only begun its run on the London stage when the coronavirus pandemic began, but one can, and should, buy it in book form. It is a wrenching and elegiac, but by no means sentimental, portrait of the life of a single Viennese bourgeois Jewish family from 1899 until 1955. It is Stoppard’s own attempt to reckon with his own Bohemian-Jewish origins. In many ways, the play beautifully conveys the thesis of Leo Strauss’s essay “Why We Remain Jews” and the political dimension of what used to be called the Jewish problem. Somehow, the play illustrates, the world adamantly refuses to let the Jews run away from their Judaism, no matter how hard they sometimes try.

Finally, for a classic work: when David Ben-Gurion was asked to recommend an account of Israel’s War of Independence, he opted for the brothers Jon and David Kimche’s Both Sides of the Hill: Britain and the Palestine War (1960, 287pp.). While the source material since then has improved a lot, and other good accounts of the war have been written, in many ways Ben-Gurion’s original recommendation still stands. A riveting account of the war which is equally as strong detailing diplomatic considerations and dealings as it is narrating key battles. This, along with Arthur Koestler’s Promise and Fulfillment (1949), on the events leading up to the war and its early days (which I recommended in a previous Mosaic “Books of the Year” installment), should be a candidate for reprint.

Michael Weingrad

The most fascinating and consequential new book I read in 2020 is Charles Murray’s Human Diversity: The Biology of Gender, Race, and Class (Twelve, 528pp., $35). Murray’s contention is that a growing body of knowledge produced by the hard sciences (genetics and neuroscience in particular) is about to sweep away our reigning academic and political dogma that insists gender, race, and class are social constructions and products of oppression. The taboo-shattering implications will be unsettling to many. Yet the book is not primarily polemical, but an engrossing, often granular tour through much of what we know today about how brains work, how geneticists study human populations, and how children’s personalities respond to and resist the best efforts of parents to shape them.

Judaism Straight Up: Why Real Religion Endures (Maggid, 218pp., $24.95) is not the title of a Paula Abdul memoir but rather Moshe Koppel’s sleek analysis of the differences between traditional, religious selves and cosmopolitan, progressive selves—or, as he names his representative of each, Shimen and Heidi. Wittily written and coolly non-theological, Koppel describes how the machinery of traditional and cosmopolitan communities work, the ways in which each is likely to break down, and how each provides for individual freedom and meaning. Take this as a placeholder for what I hope will be a longer review here in Mosaic.

“A fairytale for grown-ups” has become a bit of a cliché but it applies in a serious way to Travel Light (144pp., $12), Naomi Mitchison’s 1952 story of Halla, a cast-off princess raised by dragons. Mitchison, sister of the scientist J.B.S. Haldane and like him a sort of aristocratic socialist, wrote dozens of books during her 101 years, from historical fiction to political sci-fi, and as a friend of J.R.R. Tolkien she proofread his Middle Earth writings. Like Tolkien’s Frodo, none of the characters in this little war-shadowed book live happily ever after, but they endure their wounds and offer bittersweet solace in doing so. Odin can’t rescue Halla but gives her a piece of his cloak, and that torn scrap, along with her own determination, helps her to carry on.

More about: Arts & Culture, Best Books of the Year, History & Ideas