While the immigrant Jewish roots of American film have long been acknowledged, what remains forgotten is that there once existed a distinctive Yiddish-language cinema. Centered in pre-war Poland and the United States, it grew out of both experimental and popular theater, drawing on avantgarde and vaudeville traditions alike. Yiddish film was a bridge linking the cinematic innovations of the 1920s and 30s, from Berlin to Moscow to Hollywood, to the world of Yiddish literature, politics, and stage. With cinematic influences ranging from German Expressionism to Soviet film of the 1920s to mainstream musical comedy, Yiddish cinema is a gem to be rediscovered. While their original audience was naturally Yiddish speakers, in their 1930s heyday these movies ran in theaters throughout New York and beyond and were reviewed not just in the Yiddish press but in major newspapers like the New York Times and New York Herald Tribune. The history of Yiddish cinema, in other words, cannot be separated from that of film as a whole.

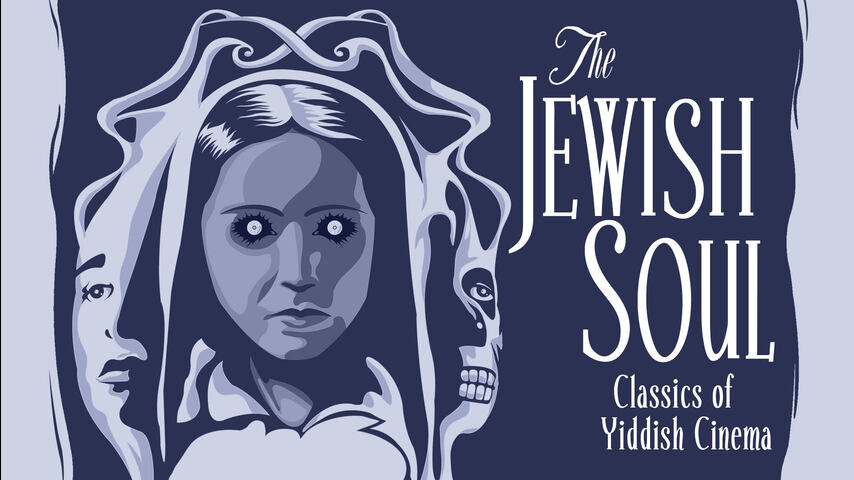

We should thus be grateful for Kino Lorber’s recent Blu-Ray and streaming release of “The Jewish Soul: Ten Classics of Yiddish Cinema,” the first collection from a major film and video distributor devoted to this forgotten body of work. Kino Lorber, which fully remastered the films and added new commentaries and subtitle translations, makes the case for these films as not just “precious documents of a vanishing culture, but a fascinating genre unto itself.”

While exposing non-Yiddish-speaking audiences to films that are valuable works in their own right, the collection exposes the thread connecting Yiddish cinema to the history of American and European movies more broadly. It also provides a new perspective on how Jews should relate to the East European past—a question that, given such recent novels as Max Gross’s The Lost Shtetl and movies like Seth Rogen’s American Pickle, doesn’t seem to be going away.

With one exception, all of the films included by Kino Lorber—two produced in Poland and the rest in the United States—belong to what has been dubbed the golden age of Yiddish cinema, which lasted roughly from 1935 to 1940. The films can be divided into two categories: those centered on Europe and Yiddish literature and lore, and those with a focus on the U.S. and the assimilation of Jews into American life. But there is also a great diversity of genres and styles, ranging from Mir Kumen On (“We Are Arriving,” 1935)—a highly stylized documentary about secular, Yiddish-speaking Jews at a leftist sanitorium for consumptive Jewish children, which uses images in ways that recall and foreshadow such celebrated filmmakers as Alexander Dovzhenko and Pier Paolo Pasolini—to melodramas like Her Second Mother (1940), with their abandoned children, forgotten parents, and inevitable happy endings. In all these films, traditional Jewish life of the shtetl serves as a central point of reference, and even those that appeared before World War II tend to treat it as a way of life that belongs to the past. One can see a clear evolution of attitudes, beginning with the triumphalism of Mir Kumen On, which depicts a forward march away from the poverty and religiosity of the shtetl to a world where Yiddish-speaking Jews work together for a socialist future. In the others, the attitude varies from ambivalence to nostalgia and romanticization.

While each movie in this collection deserves a review of its own, I will focus on three of the most impressive, which should give some sense of the works as a whole. I’ll begin with Tevya (1939), directed by Maurice Schwartz, which occupies a middle position between Mir Kumen On’s celebration of liberation from the shtetl and later films’ tendency to idealize it. Filmed in Long Island and New Jersey, but set in the old country, Tevya, like the later musical and then film Fiddler on the Roof, is derived from Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the Milkman cycle. It focuses on a single episode from those stories: the marriage of the title character’s youngest daughter Chava to a Gentile and Tevya’s utter refusal to go along with it. In his eyes, Chava is dead, and he sits shiva—the traditional seven days of mourning—for her. In the film’s conclusion, she abandons her husband and returns to Tevya and the Jewish fold.

Most disturbing about this film are the Ukrainian Gentiles, who, in contrast to the winsome portrayal of Chava’s beloved in Fiddler on the Roof, come across as grotesque and uncivilized Jew-hating brutes. Coming from Schwartz, a stalwart of Yiddish film and stage and a bohemian intellectual devoted to putting works in Yiddish on equal footing with European high culture, this lack of nuance or sympathy is jarring. But it is not so much an expression of bigotry as of Schwartz’s sense of the catastrophe looming over European Jewry in 1939, which seemed no less real for the fact that Schwartz lived in America. His Tevya is dignified and righteous, but not idealized. The holy Jewish books in his house are covered with layers of dust, rendering the idea of return to the “old, deep, and profound Jewish faith” painful and suspect, and infusing Schwartz’s nostalgia with a great deal of pessimism.

East European Jewish civilization had not yet been destroyed when the movie was made, but it had already begun to crumble—and, the film implies, could be remembered but never revived. Masterfully acted and directed, Tevya is a cinematic classic which responds to the horrific crisis of its time through recourse to what is undoubtedly the best-known work in the Yiddish literary canon—mining the richness of this source to speak to the artistic, moral, and intellectual issues of the day.

A year after Tevya, four films included in this collection appeared—Overture to Glory, American Matchmaker, Her Second Mother, and Eli, Eli—all of which exhibit the same sort of nostalgia and appreciation for tradition, but with less sophistication and with a heavy dose of sentimentalism. The first two also share with Tevya the theme of return to Jewishness and Judaism. Yet their sentimental nostalgia is very different from Tevya’s more pessimistic brand. By contrast, The Dybbuk, the collection’s best-known film, vacillates between these two modes. An adaptation of one of the greatest works of the Yiddish stage, written by the Russian Jewish revolutionary, ethnographer, and intellectual S. An-sky, it is not a melodrama or feel-good tale, but a work of expressionist horror. The director, the Jewish convert to Catholicism Michal Waszynski (né Mosze Waks, 1904-1965), went on to have a successful post-war career as a producer in Italy and Hollywood, but seems to have been haunted by this film for the rest of his life.

Waszynski perceived his Jewish past, which he strove to leave behind and keep a secret, as a ghost possessing and overcoming him. And “haunting” may be the best way to describe this work, filled, not unlike Tevya, with foreboding about the catastrophe about to engulf the Jewish world. A visual ode to that world, and especially its little-remembered occult customs and beliefs, it also depicts Judaism as a realm of death, while still making it enticing for precisely that reason. In a crucial scene—the wedding of the film’s protagonist Leah (Lili Liliana)—the bride dances with Death and is comforted by the grim reaper’s embrace. This danse macabre is a symbol of the Jewish world, at the same time decaying and alluring. The Dybbuk’s story of tragic love between Chanan (Leon Liebgold) and Leah shines in this remastered version.

Very different, at first blush, is American Matchmaker (1940), the last Yiddish film directed by Edgar G. Ulmer (1904-1972), a German-speaking émigré to Hollywood, before he turned exclusively to English. This movie serves as a bridge between the collection’s Europe-centered films and its American-based melodramas. Its main character, played by Leo Fuchs—known as the “Yiddish Fred Astaire”— takes up a career as a matchmaker out of a desire to follow in the footsteps of an Old Country ancestor. He soon finds himself almost possessed by his ancestor’s spirit. In this way American Matchmaker functions as an up-beat American counterpart to the Dybbuk, sharing its preoccupation with ghostly possession and the relationship between the Jewish present and the shtetl past. Light and humorous, it suggests that the best outcome for a Jew in America is to replicate the spirit of the Old World while partaking of what the new one has to offer. The film thus celebrates Jewish immigrants’ embrace of culture, while urging to preserve the old ways of love and marriage.

All in all, these films constitute as fine an introduction to the golden age of Yiddish film as one could ask for. Missing are any products of the simultaneous efflorescence of Yiddish film in the Soviet Union, but its curators can’t be blamed for not including everything. My single objection is to the title; appealing as it may sound, calling the collection The Jewish Soul is misleading. In the booklet included with the collection, the actor and playwright Allen Lewis Rickman, who also provided the translations and commentary to the films, speaks of them as “the soul of a great civilization: pre-war Ashkenazic Jewry.” It behooves us to recall Vladimir Nabokov’s admonition to American readers of Russian literature: “let us not look for the soul of Russia in the Russian novel: let us look for the individual genius.” Of course, in the case of cinema, this genius is often collaborative, but to search for some indefinable spirit of Yiddishkeit in these films would be equally foolish. One will, however, find in them a Jewish cinematic language that responds to and shapes the history it witnesses, placing what is happening now into a long history of Jewish experience and allowing viewers to confront for themselves the dilemmas and decisions that Jews faced with one foot in the New World and one foot in the Old.

But while we shouldn’t be tempted to leap from these films to anything so grand as the soul of East European Jewry, we can connect them to broader questions about Yiddish culture, and perhaps Jewish literature and art more broadly. In his essay “Problems of Yiddish Prose in America,” published in 1943, Isaac Bashevis Singer called on immigrant Yiddish writers to return in their works to the Jewish past and lore. Yiddish, he argued, only degenerated on the new soil and was incapable of describing the American reality. It forgets itself when it “tries to be modern, . . . mixing in many corrupted English words, making comical mistakes, and confusing one language with the other.” In choosing between the low-brow flicks and The Dybbuk, Singer, who himself was writing stories about the Jewish goblins and demons, would have clearly preferred the latter. Yet, through the Yiddish-English mishmash he scorned, found especially in the later American melodramas, these movies seem to succeed precisely where Singer thought Yiddish culture would fail. Such works certainly do away with the complexity and cinematic inventiveness of Tevya and The Dybbuk. Mixing Yiddish and English, often clumsily, and situated squarely within the here and now of America, they point to the future while joyously clinging to the norms of the past. They offer a picture of the Jew both comfortable in his skin and ultimately feeling at home in America, even if it doesn’t quite live up to its promise of being a goldene medina—the Golden Land.

If the American-centered films are engaged in an implicit argument with Singer, the Europe-centered ones, especially Tevya, participate in a dialogue with another major Yiddish writer of the period, Jacob Glatstein (1896-1971). Also a New Yorker and an immigrant from Poland, Glatstein proclaimed in his 1938 poem “Good Night, World”:

Good night, wide world.

Big, stinking world.

Not you, but I, slam the gate.

In my long caftan,

With my flaming, yellow patch,

With my proud gait,

At my own command—

I return to the ghetto.

Here Glatstein, the secular poet and novelist, seeing clearly the harsh realities of anti-Semitism in Germany, Poland, and elsewhere, as well as the scandalous indifference of the so-called “civilized world,” declares that he is turning his back on the West. Schwartz’s Tevya accomplishes something similar and, I think, was directly inspired by the poem. Both works recognize the simultaneous necessity and agony of this return to the world of tradition, which they only recently rejected. What must be appreciated is precisely the sorrow with which the likes of Schwartz and Glatstein parted with European culture, and the dread with which they encountered the “ghetto,” or what they imagined the ghetto to be.

But while Glatstein wrote a modernist poem about returning to the past, Yiddish cinema created popular art built around this theme, exploring what it would mean for an opera singer to return to being a cantor, or for an American Jew to try to imitate the life and career of a shtetl forebear. It certainly does not seem a coincidence that, with World War II underway and the fate of European Jewry in the hands of Hitler and Stalin, the Old World became something for Yiddish cinema to remember fondly rather than to rebuke.

The Yiddish screen, however, is more than a mere relic of the past or historical curiosity. It was, first of all, intimately tied to later moviemaking in other languages. After World War II, the director of Mir Kumen On—Aleksander Ford (1908-1990), né Moyshe Lipshutz—became one of the heads of Poland’s state-controlled film company and dean of the country’s most important film school. He also made both a documentary and a fiction film about the Holocaust—Death Camp Majdanek and Border Street, as early as 1945 and 1948, respectively. In 1968, he left Poland along with many other Jews, driven out by a wave of official anti-Semitism, but continued to work in Europe and the U.S.

Max Nosseck (1902-1972), who directed the 1940 Overture to Glory, cast its star—the famed cantor Moyshe Oysher—again in the 1956 English-language film, Singing in the Dark. Like Overture, it deals with an estranged Jew’s return to Judaism, albeit in the shadow of the Holocaust. But Nosseck left his real stamp on cinema with a number of gangster-themed B-movies he made during the 1940s and 50s. Likewise, Edgar Ulmer made a number of other notable Yiddish films prior to The American Matchmaker, and then went on to direct such Hollywood noir classics as Detour (1945), working with such stars as Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, and Hedy Lamarr. Both Ulmer and Nosseck were German-speaking Jews who knew very little Yiddish, and saw Yiddish film as easier to break into than English-language cinema.

But the legacy of Yiddish film doesn’t only reside in these individual connections. The melodramas sprout roots in later American Jewish cinema and reveal that the artistic ideas of Yiddish film did not die out in 1950—the year the collection’s latest film, Three Sisters, was released. Consider Paul Mazursky’s hauntingly beautiful Enemies a Love Story (1989), based on I.B. Singer’s novel of the same name. A post-Holocaust tragedy, it is also a story of a pathetic schlemiel stuck between his wives and a lover, a plotline that would have fit perfectly in a Yiddish melodrama; or Elaine May’s underrated The Heartbreak Kid (1972), with its raw and endearing portrait of a Jewish woman, Lila Kalodny, played by May’s daughter Jeannie Berlin. We can also recall Sidney Lumet’s Bye Bye Braverman (1968) and Woody Allen’s Broadway Danny Rose (1984), whose protagonist, played by Allen, is the archetypal luftmensch, peppering his speech with Yiddish words and expressions. May and Lumet came out of the families of Yiddish actors and grew up in Yiddish-speaking households. Lumet cast his father, Baruch Lumet, in a number of his films. For Lumet, the world of Yiddishkeit remained a sacred zone and the basis of his moral worldview. Both consciously and intuitively, their films feature and radiate Yiddish screen’s characters and sensibility, although now presented much more masterfully and intricately, making them in fact a maturation of Yiddish cinema.

“I should like, ladies and gentlemen, just to say something about how much more Yiddish you understand than you think,” Franz Kafka informed his German-speaking Prague Jewish audience in 1912. Watching these Yiddish films in 2021, we should feel the same way.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Movies, Yiddish, Yiddish cinema