Frum iz a galakh, erlikh iz a Yid.

“A priest is pious, a Jew is [or ‘must be’] honest [or ‘honorable’].”

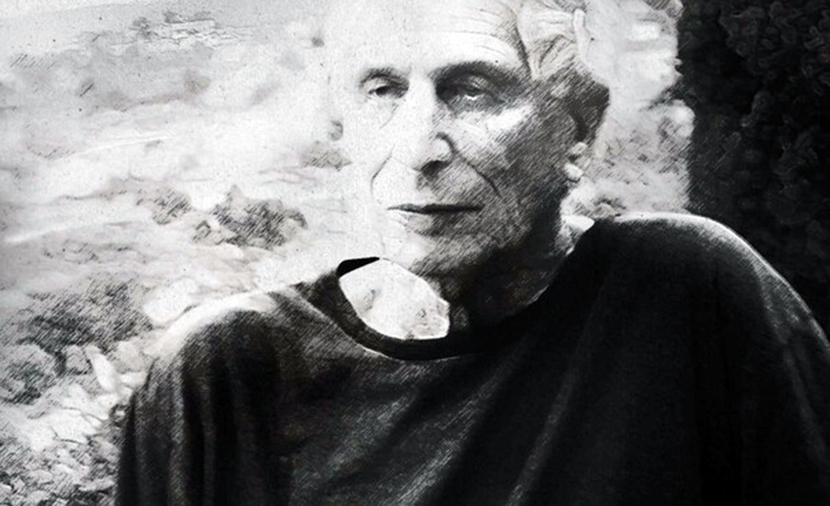

Collections of essays are never popular with publishers, especially nowadays when even the most educated people “write” more than they read. Collections usually lack the coherence of a start-to-finish book. And there are few living writers whose ruminations on this and that subject deserve to be collected. A Complicated Jew: Selected Essays is on both counts a rare exception, because Hillel Halkin is one of a kind.

Born in Manhattan just before the start of World War II, son of a distinguished professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary, Halkin’s beginnings were not atypical for post-War New York. He was schooled at the Ramaz Jewish Day School, was called to the Torah as a bar mitzvah at the synagogue at JTS where he davened with his father on Shabbat mornings, graduated from the Bronx High School of Science, and took a BA in English at Columbia, after which he studied for a year in England and then did a short stint in graduate school back at Columbia. He soon left the academic path and went on to spend most of the 1960s in sixtyish ways: developing through travel a Whitmanesque love of America; participating in the civil-rights movement and teaching for a year at a black college in Alabama; buying 150 acres in Maine on which he intended to live in a log cabin. But in the aftermath of the Six-Day War and newly married, Halkin said goodbye to all that and made aliyah with his wife Marcia in 1970, soon taking up residence in a house he had built for them on a one-acre plot in the romantic hilltop village of Zichron Yaakov.

In the succeeding five decades, while tending his own garden and raising his Israeli family, Halkin earned his living—and his considerable reputation—as an independent and multifaceted man of letters: translator of Jewish texts from both Hebrew and Yiddish (from Amos Oz and A. B. Yehoshua to Sholem Aleichem), Zionist apologist (Letter to an American Jewish Friend), Zionist historian (A Strange Death), biographer (of Yehuda Halevy and Vladimir Jabotinsky), novelist (Melisande! What Are Dreams?), Jewish thinker (After One-Hundred-and-Twenty: Reflecting on Death, Mourning, and the Afterlife in the Jewish Tradition), literary critic (The Lady of Hebrew and the Lovers of Zion, serialized originally in Mosaic), and public linguist (writing as the columnist “Philologos,” also now in these pages). Yet Halkin is probably best known as an essayist, a master of the genre, writing in the self-conscious and invitational spirit of its originator, Michel Montaigne, albeit in a decidedly Jewish key. Deftly mixing personal experience and erudition with astute social and cultural insight, Halkin illuminates the widest range of subjects in all their complexity and subtlety.

It was as an essayist that I first encountered Halkin, during the 1970s, in the pages of Commentary. I devoured his contributions as soon as they arrived, finding them inviting, sharp, lively, literate, thoughtful, humane, and, above all, truthfully written. My exact contemporary (though I am Chicago-born and bred), Halkin spoke directly to the world of my experience and to my Jewishness, but in ways that enlarged my vision and challenged my prejudices. This was an author I would have loved to meet.

A chance encounter at a Tikvah Fund summer program at Princeton University brought us together some ten or so years ago, and a treasured friendship sprang up between the Halkins and the Kasses from occasional Jerusalem meetings while my wife Amy was alive. The special experience of growing up in 40s and 50s New York formed an immediate bond among Amy (High School of Music and Art), Hillel (Bronx Science), and Marcia (High School of Performing Arts). And I took special delight in discovering that Halkin in person was even more likeable than he was in print—in my experience a rarity, as I have almost always been disappointed upon meeting authors I have admired. So, when I learned that Halkin was publishing a collection of his essays, I volunteered to re-read the essays I had long ago admired, now with the advantages of age and in the light of my new friendship with their author.

Re-read them I have done, again devouring and savoring as I went, each in its own terms. But I have had to re-read them a second time and, indeed, now a third. For thanks to some explicit literary hints Halkin drops before his readers, I quickly realized that this was no haphazard collection of the author’s favorites. The first words of the preface alert us to a larger intention:

The eighteen essays selected for this book were published over a period of nearly half a century, the first of them in 1974, the last in 2021. (Emphasis added)

Eighteen is the numerical equivalent of chai, the Hebrew word for “life.” We are invited to suspect that these essays may constitute an autobiographical overview, unorthodoxly given, in a lifetime’s worth of literary attempts.

The second paragraph supports this suspicion:

I have not arranged these essays in the order in which they were written. Rather, I have sought to give them an autobiographical sequence. Thus, the book’s first entry deals with my family’s origins in Eastern Europe, its second and third with my New York childhood and adolescence, and so on.

Essays written over nearly half a century, all personal to be sure but none written with autobiographical intent, are now reproduced (largely unaltered) in an order that, Halkin tells us, will reveal something of his entire life.

What, we wonder, does Halkin want us to understand about his life? What, after family origins and New York childhood and adolescence, will we learn from the “and so on”? Can one write or order an understanding of one’s life by rearranging one’s earlier writings so that an essay from one’s youth serves to reveal the truth about one’s later life?

Lest you think I am reading too much into these innocent words of introduction, I give you the very last words of the collection, from Halkin’s latest essay in the book, a 2021 review of Winter Vigil, the posthumously published memoir by Steve Kogan, a friend of Halkin’s from their graduate-school days at Columbia:

The year I was a student in England, I had a tutor, a poet and a mystic, who once said to me, “You know, you spend the first part of your life working your way into your incarnation and the last part working your way out of it.”

I didn’t know what she was talking about. How could I? I was still working my way in. Today, I think I get it. I would just phrase it differently. I would say you live a life that’s messy with experience and clean up by leaving something complete. You don’t do that by throwing anything away. You do it by putting everything in its place.

I cannot but think that this collection of his essays is Halkin’s attempt to put everything in its place.

But what is that place? What does it all add up to? For that, we get unexpected—and I suspect unintended—help from the title. In the preface, Halkin tells us how the title was chosen:

When it came to a title for this [book], neither its publisher Adam Bellow nor I had any bright ideas. “I suppose it should have something to do with being Jewish,” I said to Adam. All this book’s essays, after all, were written for Jewish publications and touch on some aspect of Jewish life or thought.

“Well,” Adam asked, “what kind of a Jew would you say you were?”

“A complicated one,” I said.

Which is how, quite spontaneously, the title of this book came about. I will not try to justify it in this preface. The essays themselves, I believe, do that well enough.

The descriptor “complicated” implies multiplicities and internal tensions, and the essays reveal them in spades. But for me, the deeper question has to do with the unity and persistence of the noun: through all the variations and complications, Halkin lets us know from this apparently accidentally chosen title that he has remained from start to finish a Jew—not accidentally, but essentially. It was in search of this essence that I had to read and re-read again: to discover not the kind but the crux of Halkin’s Jewishness, as it emerges when he has at last put “everything in its place.”

Before trying to formulate what I think Halkin has revealed about his Jewish essence, and to enable the reader to join me in this quest, I must speak about the individual essays, all little gems; all personally moving, a few of them to tears. Because I am chasing his identity and am looking at the essays with this singular focus, my synopses necessarily shrink the fullness of each essay. They also abstract from the particular subtleties and richness of Halkin’s prose. To compensate, I will liberally let him speak, to give you a taste of his literary gifts.

Literary Gifts

The opening essay, “The Road to Naybikhov” (1998), features Halkin’s return, at age fifty-eight, to his father’s shtetl, in search of his long-dreamed-of East European roots. Unlike most such pilgrims, Halkin had amplified his dreams by immersing himself in the vibrantly self-conscious Hebrew and Yiddish literatures produced by shtetl-dwelling writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As he travels the country roads of Belarus, he imagines ghostlike before him “a wagon with a Jew in it.” But, alas, “horse-drawn wagons are plentiful; Jews are rare.” Like other disappointed pilgrims, Halkin discovers “it was not the place that had meaning but the people.”

Yet, miraculously, his search was not in vain. He is shown the spot where lived his family’s next-door neighbor, the Gentile who served as their Shabbes goy. And from that spot, having filled a can with ancestral soil, he sees the land sloping down to the Dnieper below, exactly as he had pictured it in his childhood dreams and as his uncles and aunts had described it. The ghosts of his origins return with the help of shtetl literature recalled, and they bear heartache for its vanished time. The origins of our complicated Jew, he recognizes, are tragic: the shtetl’s literary world of secular Yiddishkeit was doomed by the forces of modernization that created it, even before the Holocaust literally destroyed it. Nostalgia, longing for home, will be a guiding nerve of this book and of Halkin’s life.

In the second essay, “Rooting for the Indians” (2007), Halkin gives us his nine-year-old New York schoolboy self, innocently managing the challenge of being both an American and a Jew. True, he is bullied and humiliated over his kippah by a throng of Jew-hating Irish toughs as he returns home from Sabbath services. But in 1948 America, baseball offered everyone a royal road to belonging, and Halkin became a fanatic for baseball and for the Cleveland Indians. (Already a contrarian and a lover of words, he refused the banality of rooting for one of the great local teams—Yankees, Dodgers, Giants—and chose the Indians because he liked their name, a name the team has just now been shamed into abandoning; perhaps Halkin can write the sequel, “Saying kaddish for the Indians.”) In the essay’s best moment, Halkin describes running home from Rosh Hashanah services to hear the broadcast of the playoff game between the Indians and the Red Sox, won by the Indians en route to their World Series victory—what Halkin calls his fandom’s “beginner’s luck.”

But the summer of 1948 was also the war for Israel’s independence, arousing Halkin’s Zionist passion and yielding a victory more meaningful and enduring—and more costly—than baseball. In the essay’s last words, describing his ordeal of fasting for the first time during that year’s Yom Kippur services, Halkin recalls:

Then the shofar was blown—this time loud and clear—and everyone exclaimed hoarsely, “Next year in Jerusalem!” while hurriedly putting away his prayer shawl. It was—I knew it, half-dead though I was—the most sensible prayer of the day.

Could the nine-year old Halkin have already divined his own answer to the divided existence he was then, more or less happily, able to lead?

The tension between American and Jew comes to a head in the pivotal third essay, “Either/Or” (2006), an account of Halkin’s teenaged years. He transfers after eighth grade from Ramaz, where around the time of his bar mitzvah he had become very devout, to Bronx Science, where gradually and not altogether happily he sheds most of his Jewish faith, as had many intellectually inclined Jews before him as they ran into modernity.

I was a country at war in which the fighting was moving steadily closer to the center: first the outlying districts were taken, then the provincial towns, then the roads leading to the capital. Each time another position was overrun I fell back and threw up new defenses; each time, they were overrun again.

Yet looking back 50 years, Halkin comes to a remarkable conclusion. His, that is ours, was the last generation that looked at the world through either/or glasses. Subsequent generations of Jews, whether from having made their peace with modernity or from surrendering a concern for “truth” to the easy-going relativizing of post-modernism, felt no need “to decide between the rabbis and Spinoza, God and Nature, Genesis and The Origin of Species.” But, as a matter of intellectual probity, “we were told [at school] to think in terms of ‘either/or,’ not of ‘both/and.’”

Born two months before the outbreak of World War II, I fought the battles of a 19th-century Jew. My faith in the Jewish God was like a soldier tragically killed, for no good reason, in the last hours of combat before an armistice is signed.

As we read ahead, we should keep both “either/or” and “both/and” firmly in mind, and also Halkin’s seeming—or ironic—regret over his loss of faith in God, “for no good reason.”

His religious faith in retreat, Halkin “fell in with the literary crowd,” adoring Thomas Wolfe (I did too) and leftish folk music (ditto). And, thanks to a summer spent out of New York doing farm-labor in Tennessee and encountering “the real America,” Halkin “fell romantically in love with his native country at the age of sixteen.” Yet this turn only intensified his self-division:

I myself was now to lead not one secret life but two, each with its own set of friends. In them, I didn’t speak to my “Jewish” friends about my American side, and I didn’t speak to my “American” friends about my Jewish side, and the Jew and the American within me did not speak much to each other, though they fought fiercely enough when, like moles whose tunnels have crossed, they sometimes met.

Where, we are left wondering, will this subterranean conflict lead?

The next essay, “The Great Jewish Language War” (2002), introduces a further dichotomy, this one within the Jewish camp: the great culture war over which is the true language of the Jewish people, Hebrew or Yiddish—the (globally used) language of the Torah, Talmud, and high culture or the language of (Eastern Europe’s) everyday life. Halkin, raised by Hebraists (I, by Yiddishists), displays his capacious knowledge and appreciation of Jewish writing in both languages and argues convincingly that the language war did not really exist among the writers. It was, in fact, not a cultural but a political conflict. Moreover, although the language war was long ago settled in favor of Hebrew, the problematic political attitudes of the earlier Yiddishists persisted—and still persist—in America, even though their language has all but disappeared:

They [the political attitudes] include the belief that Zionism was a mistaken political strategy for the Jewish people; that an identification with Israel need not be a central feature of Diaspora Jewish life; that minority status in the Diaspora is the optimal Jewish cultural and spiritual condition; that the political interests of Diaspora Jews lie in the forging of alliances with as many “progressive” and left-wing causes as possible; that solidarity with non-Jewish victims of capitalism, colonialism, racism, and other injustices is more important than solidarity with other Jews; and that the very notion of other Jews, of that klal yisra’el or collectivity of the Jewish people that all Jews traditionally felt responsible to, can be trimmed at will to suit one’s ideological proclivities.

Not surprisingly, Halkin’s next essay finds him in Israel.

“Holy Land” (1974; the book’s earliest essay) is, however, not about Zion, the Jews, or the conflict of personal identity. Instead, a thirty-five-year-old Halkin celebrates in exuberant detail what it means to own and manage his own land, an acre that is holy-to-him by virtue of ownership, not because it is in the Holy Land. We meet the resident flora and visiting fauna, learn about a property dispute with a neighbor, and are brought—with Halkin—to a historical consciousness when he discovers a burial cave on his property some 1,500 years old. Moving away from his youthful belief that “Everything is holy,” he has learned that “it is but a short step from believing that everything is holy to living as though nothing were.”

He resists the idea that his land in Israel is holier than his former land back in Maine: “both smell equally good after a rain and the mosquitoes in summer are as annoying when encountered on either.” He confesses to “the occasional wish as a Jew that the rest of the world would take its shrines elsewhere and leave us to putter around here by ourselves.” But he has little hope that Israelis, their land become familiar, will prefer cherishing it to exploiting it. Better, then, to revere your own portion of the land by preparing and tending your own garden, about which Halkin waxes eloquent and philosophic. Young Halkin, although married with child and living now in Israel, speaks like the romantic son of the 60s that he then still mainly was.

But these were no longer the 60s, Zichron Yaakov is not rural Tennessee or backwoods Maine, and the differences soon loom large. In “Driving Toward Jerusalem” (1975), Halkin describes in hauntingly beautiful detail (beyond my ability to capture) what he saw and what he thought and felt while driving from Haifa to Jerusalem through the Arab towns and villages of Samaria: from Haifa to Jenin; from Jenin to Nablus; from Nablus to Ramallah; from Ramallah to Jerusalem. He evinces great respect and sympathy for the Palestinians, admires their rootedness in the land, and wrestles in conversation with himself about what might be done to resolve the conflict, even proposing a two-state solution with open borders, two peoples sharing one land, a wildly heretical idea in the wake of the Yom Kippur War. But his arrival in Jerusalem is melancholy:

Ah, Jerusalem! If ever a city has huckstered the world for a living with its mosques, churches, synagogues, crypts, caves, walls, tombs, stones, bones, and souvenirs, it is you. And the world will not admit it has been taken and will not leave you alone. French Hill. Mount Scopus. Sheikh Jarrah. Outside the American Colony Hotel, a party of tourists is boarding a waiting bus. They are pink-faced, innocent of passion, and if the postcards they send home are to be believed, they are having a good time. For a moment it almost seems to me that I hate them. Or is that warm flash of feeling rather an unreasonable burst of affection, call it love, for the little Arab boy, a hole in the knee of his pants and no laces in his shoes, who is trying to sell them some worthless wooden trinket? He badgers them; they retreat into the shadow of the bus. We are accomplices in this land, he and I, and will be here when they are gone.

Yet living in Israel, Halkin cannot just tend his garden and think feelingly about his Arab neighbors. He must serve in the army reserves, the setting of “My Pocket Bible” (2008), named for a small bible bearing the IDF insignia that he was given on completing basic training in 1974. Halkin is assigned to an anti-tank gun company, which is also asked to patrol the border with Lebanon, facing off against the Palestine Liberation Organization. This stunning essay recounts a night of guard duty shared with a religious soldier of French extraction, a man Halkin would never have encountered in civilian life, the army being Israel’s national melting pot. The man had been wounded in the Six-Day War after which his wife, taking their child, had left him—and left him furious. Having seen Halkin reading Parashat Vayera in his pocket bible—note that the reservist Halkin at the Lebanese border is not praying but reading Torah—the man provokes a conversation about Sarah and Abraham, and the latter’s near-sacrifice of his son, Isaac, known in the tradition as the Akeidah, offering the most astonishing—indeed, disturbing—interpretation of their marriage one will ever hear. (I will not spill the beans.) Where else in the world would nighttime guard duty feature biblical exegesis between total strangers? Halkin, albeit ironically, thought the same and concluded by quoting the evening prayer:

Therefore, O Lord our God, when we lie down and when we rise, may we converse about Thy laws and rejoice in the words of Thy Torah, for we shall think of them by day and by night.

In Israel, the ghosts of the biblical past walk the land by night, orienting the living—even the disaffected—to find meaning in (their own) Torah.

The powerful next two essays deal, in fact, with disappointment and disillusionment, first, cultural, those of Halkin’s uncle, Simon Halkin (“My Uncle Simon,” 2005), then, political, Halkin’s own (“Israel and the Assassination,” 1995). Simon Halkin—Hebrew poet, novelist, and literary critic—was called in 1949 from New York to head Hebrew University’s department of Hebrew literature. A deeply religious and passionate man of enormous learning and erudition, both Judaic and Western (he translated Whitman’s Leaves of Grass into Hebrew), Simon Halkin championed a new Hebrew literature for Israel, a synthesis of the best works of the Western and Jewish mind but informed by traditional Judaic obligations of self-perfection and self-purification. Hillel Halkin’s loving portrait of his uncle, whose Zionism had always been his model, finishes with an account of the tragic collapse of that cultural Zionist vision.

The 1970s in Israel were years in which the center fell away, splitting the country into two warring halves, a heavily secular left and a heavily religious right, that were no longer talking the same language. . . . A particularism that jeered at universal values clashed with a universalism that scoffed at the particulars. It was as if, from the most superficial level of rhetoric to the deepest psychology of those using it, Judaism and Humanism had become unglued.

Either/or, even in the Jewish homeland.

It was worse than that. The cultural greatness of Simon Halkin’s generation, as he himself bemoaned, could not be passed down to the next generations: “We have become a county of khnyokes [religious prigs] and amarotsim [ignoramuses].” High cultural Zionism had flowered magnificently but was now wilted, due (partly) to a defective educational system and the triumph among the young of a vulgarized street Hebrew. Although not himself ready to toss in the towel, Hillel Halkin gives his Uncle Simon the last word: “If I had known how all this would turn out, I would have gone to North Dakota and lived as a Red Indian.” Hillel Halkin’s dream of Zion, like that of his uncle, was vulnerable to time and events.

From his youth a man of the (sensible) left, Hillel Halkin’s reaction to the assassination of Yitzḥak Rabin must have astonished his friends. Although sharing everyone’s horror of the event, he nonetheless blamed the Labor party and the left for its outsized role in polarizing the country, beginning with its dishonesty regarding the Oslo agreement with the PLO and continuing with its cynical demonization of Benjamin Netanyahu and the religious right (for example, Yeshayahu Leibowitz’s crack about “Judeo-Nazis”). In a profound reflection on the deeper sources of the political split, Halkin traced it to the failure that had disheartened Uncle Simon:

the failure of the grand cultural project of Zionism, whose root assumption, once shared by secular and religious Zionists alike, was that it was possible to build a society that would combine a commitment to the modern world and its highest ideals with an allegiance, if not to the ritual forms, at least to the great texts and memories, of Jewish tradition and their resonance in the physical landscape of Israel.

The cultural split into religious and secular factions was accelerated, Halkin correctly observes, by the growing Jewish settlement of the West Bank and the Palestinians’ violent resistance to it, culminating in the intifada(s). The national “either/or” dilemma, begun at Oslo, continues to this day, with no political solution in sight:

Either Israel relinquished its title to Judea and Samaria, the geographical core of the historical Jewish homeland, and so, by freeing the people living there from its yoke, took its stand (said the left) with enlightened humanity; or else it pressed its claim to the areas and kept faith (said the right) with Jewish memory.

This was a cruel dilemma. And it represented a great irony, for it meant that the Jewish state, which according to Zionism had come to heal the inner split between the human being in the Jew and the Jew in the human being, had now driven a new and terrible wedge into the breach.

Like a man in great torment who breaks psychologically in two, Israel thus went, or was dragged, to Oslo as two nations, each willing to risk what the other was not and unwilling to risk what the other was; neither able to communicate with or to understand the other but only to blame the other rancorously; thesis and antithesis, each half of the now-fractured personality of the Jewish people in its homeland. [Emphasis added.]

We are at the exact center of the book, between essays nine and ten. What does a politically disillusioned, cultural Zionist like Hillel Halkin do now? He doubles down on where his heart and talent had already taken him: keeping alive the treasures of Jewish and Zionist literature and thought.

Halkin has been engaged in translating Hebrew and Yiddish texts for six decades, increasing access to them for thousands of English readers. In a searching exploration and assessment of that activity, “The Translator’s Paradox” (2008), Halkin is acutely aware of the mixed blessing of being a Hebrew translator today. For the price of increased access through translation has been the loss of Hebrew as the international language of the Jewish people, contributing to the growing cultural gap between Israel and the Diaspora:

Here, then, is a great historical irony. As long as Hebrew was the first language of no educated Jew in the world, it was the second language of every educated Jew; now that it has become the mother tongue of millions of Jews in the state of Israel, it has largely ceased to be known by Jews elsewhere. It has in effect been demoted to a Judeo-Israeli, a new Jewish regional speech. Far more Israeli and Palestinian Arabs now have a working command of it than do American Jews.

Unusually perspicacious, Halkin recognizes a still deeper cost of translation: “Translation dilutes the culture it disseminates, weakens Jewish distinctiveness, puts Jews at a remove from themselves. It makes them vulnerably transparent to the world.”

A people’s language is its private domain; in it, it can pursue its own business, conduct its own quarrels, make its own jokes, let down its hair; it can be itself without fear of eavesdroppers. One can argue in a Jewish language about Judaism, about Zionism, about any aspect of Jewish life, but one argues in that language, not about it; the language itself belongs to all. Precisely because it is neutral, language has always been the strongest of communal bonds, the magic circle that no interloper could cross.

For the first time in their history, most [Diaspora] Jews no longer have a language of their own. They are overheard when they speak to each other.

How many people do you know who are as acutely aware of the limits and dangers of their craft, and who would take it—and themselves—to task in the name of the Jewish people? Other people who traffic in Jewish texts for their own purposes lack Halkin’s scruples and loyalties. Halkin, in the sequel, does not give them a pass.

In the next two essays, “Feminizing Jewish Studies” (1998) and “How Not to Repair the World” (2008), Halkin responds to fashionable new developments in Jewish thought that rush to give Jewish cover to progressivist ideas about gender and social justice. The logic of the innovators is shameless: major premise, Judaism is good; minor premise, progressivism is good; conclusion, Judaism is progressivism. As Halkin puts it, most of them do not treat tradition as a mentor but rather “as a surrogate mother who can be hired to bear any child one wishes.” Vastly more knowledgeable and Jewishly loyal than the tenured radicals, Halkin deftly demonstrates their ignorance of Jewish thought and detachment from the Jewish tradition and exposes their indifference to the consequences their ideas will have for the Jewish people and for Israel. These essays, timely when written, are now even more salient, given the galloping cultural madness afflicting the United States.

But what about Israel, and what about its relation to the rest of world Jewry? In what is the most philosophical (and, except for the last page, the least personal) of the essays, “If Israel Ceased to Exist” (2007), Halkin takes up the profound question of Jewish destiny in a world in which, he argues, Israel and the Diaspora have lost their illusions about each other. Prior to the birth of the state, the central idea of Jewish identity was exile and return, the dream of Zion. But now that return is possible, the choice of most American Jews to stay put has exposed the narrative of return to be a myth, increasing cynicism in Israel about the dedication of Diaspora Jews. Conversely, many American Jews are let down by Israel, which turns out not to be “more advanced, rational, and morally refined than the goyim.” For marginal American Jews, most of them liberals, Israel no longer gives them any sense of Jewish uniqueness. And when Israel’s conduct embarrasses their liberal ideals, they feel less reason to remain Jewish: “Today, Israel is more a spur to assimilation than a bulwark against it.” The new dispensation, in other words, is that the existence of Israel has, paradoxically, forced Jews everywhere to surrender their illusions about themselves; “it has brought the Jewish people down to earth”—and Halkin, not a fan of self-deception, seems pleased about this.

But that is only half the story. Alas, the world still chooses to treat the Jews and Israel as special, whether among evangelical Christians for good or among anti-Semites (now on the rise, even in America) for evil. Under these circumstances, Halkin worries that the Jews will slip into a new secular delusion of national specialness:

Israel and the Jews as the front line of democracy, Israel and the Jews as the standard bearers of Western civilization, Israel and the Jews as the world’s shock troops against Islamo-fascism, Israel and the Jews as the canaries in the coal mines of the new barbarism and so forth—anything, in a word, but Israel and the Jews as a small country and people that have carried the burden of specialness long enough and paid too heavy a price for it.

This is not to say that all of these things may not, in some sense, be true. It is simply to observe that Jews should not hurry to embrace them without an awareness of the inner need they serve—the need to recover that belief in their own uniqueness, as a people chosen by history if not by God, that they have lost but still crave.

If the heavy burden of Jewish history has to be shouldered by them once more, should they at least not know clearly what it consists of?

In a shocking conclusion, Halkin places all his Jewish marbles on Israel: “If Israel should ever go under, I would not want there to be any more Jews in the world. What for?”

Things haven’t been this good for the world’s Jews in 2,000 years. In one respect only are they worse. During that period, we were a people that had lost a first temple and a second; yet as great as our misfortunes were, we did not have a third temple to lose. Today, we do. If we cannot safeguard it, it would be as shameless as it would be pointless to want to go on. In Jewish history, too, three strikes and you’re out.

Arresting words. For me, an American Jew with growing ties to Israel, disturbing words, especially as I concede all of Halkin’s worries about the future of non-Orthodox Jewry in the United States.

And yet, to quarrel for a change with Halkin, I wonder whether he has not sold short the emergence of new forms of moral and spiritual Jewish engagement among the rising generations, both in America and in Israel, people who will not follow rabbinic Judaism but who have a God-shaped hole in their heart and who sense that the Torah and Jewish thought can fill it, both for themselves and for their communities. When I am in Israel, I feel that I am in the Promising Land, not because of its high-tech and medical advances but because it exudes hope in the Jewish national future, still informed by ancient Jewish wisdom and attachment to tradition. And although I am increasingly depressed about American culture, the renaissance of interest in Jewish texts, thought, and tradition—through Chabad on campuses, through the Tikvah Fund’s burgeoning online and summer programs, and through the emergence of new prayer-and-study groups in major American cities (and, by the way, also in Israel)—encourages me to think that a God-seeking light unto the nations may still and again shine brightly. Not cultural Zionism and not tikkun-olamism, but the Jewish future may yet be renewed by an embrace of our moral and religious heritage, a heritage that we treasure not only because it is ours but mainly because it is good. The Jewish people, still here against all odds, still called to reject idolatry and to pursue righteousness and holiness, still gathering for study and prayer, still failing and holding themselves accountable but never surrendering the aspiration, are not, I would insist, just any old people.

Seemingly to support my point about a revival in Jewish thought, Halkin’s next two essays discuss remarkable new contributions to Jewish prayer and Torah study: the new Koren Siddur, with commentary by the late Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks (“Endless Devotion,” 2010), and Robert Alter’s monumental translation of the entire Hebrew Bible (“The Robert Alter Version,” 2019). But the appearance of the new prayer book becomes instead an occasion for synagogue-absent Halkin to question the worth of ever-longer prayer services and of prayers recited by rote without concentration and feeling. He analyzes the structure of the daily prayers, sheds light on their historical development and growth, and celebrates some of their beautiful poetry, along the way assessing the merits of Rabbi Sacks’s translations. Ironically more than many praying Jews, Halkin seems to appreciate what prayer is supposed to do.

His suggestion comes in his discussion of Shabbat’s musaf service, instituted as a substitute for the animal sacrifice that was performed while the Temple stood in Jerusalem. Although by no means eager for the reinstitution of bloody sacrifices, Halkin has grasped the limited capacity of the prayer book to bring us any closer to God, to express as animal sacrifice did “the passionate wish . . . to be able to offer to God what is most precious.”

[A]nd what is most precious is not the words that we say day in and day out. Words are what the siddur has accumulated, more and more of them, as though in the fear that there can never be enough. Some move us more and some move us less, but none grabs us and shakes us until we feel faint. We yearn for the prayer that cuts to the quick like a knife.

Halkin’s comment cuts to the quick: what can we say for our praying selves in the light of this challenge?

Halkin’s treatment of Alter’s epic translation is thorough and judicious. He begins by recognizing its stupendous achievement: “One might call it the translator’s equivalent of a solo circumnavigation of the globe were it not that sailing a boat around the globe takes far less time.” He appreciates Alter’s devotion to faithful rendering of the text, honoring its careful poetic and prose styles. He undertakes a comparative assessment of Alter’s translation and the King James Bible, looking carefully at the creation story of Genesis 1, the theophany of Isaiah 6, the stories of the binding of Isaac and of Jephthah’s daughter, and the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20, showing why one or the other translation is superior. His most pregnant criticism of Alter comes when Halkin faults him for replacing, in translating the Decalogue, the second-person intimate singular “thou” (“Thou shalt not commit adultery”) with the non-specific and impersonal “you.”

“You” can be either singular or plural and addressed to everyone. “Thou” is addressed to me alone. I am the person in the crowd at whom it points its finger and says, “You there, I’m talking to you!”

The Bible points to each one of us. It says, I may be masterfully written, but this is only a means to an end. The end is your obedience. Do not mislead yourself into thinking it is anything else. [Emphasis in original.]

Halkin concludes, using help from Erich Auerbach’s famous comparison (in his 1946 work of literary criticism, Mimesis) of the prose of Homer’s Odyssey with the story of the binding of Isaac, with what amounts to a devastating critique of Alter’s reading of the Bible as literature. Says Auerbach: “The Scripture stories do not, like Homer’s, court our favor, they do not flatter us that they may please us and enchant us—they seek to subject us, and if we refused to be subjected, we are rebels.” Says Halkin, in sentences that burn on the page:

Reading the Bible as literature remains an act of rebellion today, if not against a divine Giver of it who no longer commands our credence, then against the Bible itself, which does not wish to be read in this way. It is to read the Bible not so much without faith as in bad faith, although what better faith can be hoped for from the faithless than the faith in literature, which alone holds that every word in the Bible counts even if it is not God’s, would be hard to say.

We should not be surprised that the supremely literate and literature-loving Halkin’s next essay is about literature and about his beloved Odyssey—and mine.

“Sailing to Ithaca” (2005) recounts a sailing trip Halkin took to Ithaca in search of Odysseus. This is my favorite essay in the book, not least because my wife Amy and I also made such a pilgrimage, in 1980, on our only trip to Greece. The Odyssey was Amy’s favorite book to teach, the subject of three beautiful essays, and treasured by both of us for its celebration of marriage and home and its magnificent storytelling. Although Halkin found no trace of the landmarks mentioned in Homer’s Ithaca, and although he knows that scholars now believe today’s Ithaca is not Homer’s, it still mattered to him to think that “I was on Homer’s Ithaca.” His reason: “It would make as much sense to tell someone searching for a grave in a cemetery that its exact location doesn’t matter, since most tombstones look alike. The search is not for a different-looking grave, but for the right one.”

This analogy immediately launches Halkin into a reflection on death, loss, and memory, beginning with this stunning and self-revelatory claim: “Deep down, the dead live mysteriously on for us; this is the oldest layer of human religion and perhaps its sole ineradicable one.” Could it be that Halkin’s own religious disposition here reaches its deepest ground?

The sequel’s poignant phenomenological discussion of loss and restoration in the Odyssey reveals, more than anything in the book, the depth of Halkin’s soul. The writing is exquisite, the insights profound. No stranger to lost love, I read these pages with tears of sorrow, mixed with gratitude for words that cut to the truth of things, in their fragile beauty. Haunted by the evanescence of things and the shades of experience past, Halkin, a now-wiser romantic, champions “l’ḥayyim” but with the deepest awareness of its limits:

The truest words spoken at the Odyssey’s end are hers [Penelope’s] when, responding to her husband’s crestfallen anger at her initial failure to recognize him in his disguise, she says: “Be not vexed with me, Odysseus, for . . . it is the gods that gave us sorrow, the gods who begrudged that we two should remain with each other and enjoy our youth.”

The Odyssey is a fairytale, the most wonderful ever written. What distinguishes a true fairytale, after all, is not its fairies, much less the good luck of getting something for nothing, but, on the contrary, the principle of getting something for something: of love, faith, and steadfastness always having their commensurate reward. L’fum tsa’ara agra, the ancient rabbis said: “As is the suffering, so is the recompense.” But the rabbis were thinking of the World to Come. In the Odyssey, there is only this world.

But just when one might think Halkin has left Jerusalem to sail for Athens (okay, Ithaca), he comes about with the help of another passage from Auerbach’s classic essay comparing Homer and the Bible. Beginning with the Akeidah as the exemplary case, Halkin argues that, in the Bible and unlike the Odyssey, there is no simple restoration of what was lost: “Even when you think you have back what was taken from you, you have gotten back something else.” In the Bible there is no simple return. There is instead development and direction, redemption of the past by building it into the future.

The redemption of loss—the idea that, although nothing can be restored, everything that has happened can be changed by adding to it, so that the past is always with us and continually still taking place—is a biblical concept. You won’t find it in the Odyssey.

This, too, is different from a belief in happy endings. The life of the real Abraham and Sarah is even more unlikely to have ended happily than that of the real Odysseus and Penelope. The consequences of a man trying to kill his own son are too great. But there is an interconnectedness of things that extends beyond Homer’s ken. Because a knife was laid on Isaac’s throat at Mount Moriah, Israel receives the Torah at Mount Sinai.

Parting ways with Odysseus and Homer, Halkin’s next (and penultimate) chapter has him back engaged with the Torah, and precisely with the laws and ordinances given at Sinai.

“Law in the Desert” (2011) gives us Halkin’s mature thoughts about the Torah—not about how it should be translated but about how it should be read. We get his personal feelings and reflections, unmediated and unfiltered, revealing what we might regard as the emerging wisdom of his old age. For many years, Halkin’s appreciative reading of Genesis and the narrative first-half of Exodus came to a screeching halt with the weekly portion Mishpatim (Exodus 21-24), God’s dense recitation of the ordinances that followed the dramatic announcement of the Ten Commandments. And the subsequent weekly portions, known as T’rumah and T’tsaveh—presenting the boring instructions for building the Tabernacle and clothing the priests—were for him equally unreadable. Whereas Rashi could have gladly dispensed with the narrative antecedents in order to concentrate on the Law, Halkin would for years abandon his reading on law’s threshold: “Three or four times over the years I reached the commandments. Three or four times I got no further.”

Early in his eighth decade he decides on Rosh Hashanah to try again, this time reading from the Latin Vulgate translation of the Christian church father Jerome. He starts, as before, with little regard for the Law and confesses sympathy for Paul, who saw in the Law no merit beyond the knowledge of our sinfulness, to be redeemed by God’s grace through his son:

He [Paul] was raised, as I was, in the world of Jewish observance, and while he felt, like me, too cramped by it to remain in it, he was too attached to it to let go of it without a prolonged inner struggle. He longed to link up with the rest of humanity while remaining the Jew that he was, and by repudiating the Law in the name of the Law he found a brilliant if tortured way of doing so. Long before Spinoza, he was the prototype of a certain kind of modern Jewish intellectual.

But this time through, an older and perhaps wiser Halkin discovers, with the aid of the story of the golden calf, the true value and absolute necessity of the Law. The Law (and, I would add, especially the Law of the Tabernacle) is no interruption of the narrative, but a way of addressing the wildness and wickedness lurking in the human heart that erupt in the orgiastic worship of the golden calf—exactly while the Law of the Tabernacle is being given to Moses. Just as God’s first efforts (reported in Genesis) to have human beings live decently without law failed when all life corrupted itself before the Flood, so his second effort with the Israelites was nearly aborted because they had corrupted themselves while still standing at Sinai.

Halkin has come to see the necessity of the Law—not only the written, but also the oral law. He marvels at the efforts of the Jewish sages to expound the Law, arguing among themselves about its meaning, but never departing from its guiding authority:

[T]he whole vast edifice of Jewish law . . . suddenly towered above me, this edifice, in all its architectural immensity, dizzyingly tall—explication upon explication, disagreement upon disagreement, complication upon complication—and for the first time, though I had never gotten beyond its bottom floors, I felt that I grasped its full grandeur—the indomitable scope of its determination to make up for the golden calf. Century after century, the Jews had labored to convince God that He was right not to have given up on them at Sinai—that His pilot project could still work, that they would devote themselves to it endlessly, tirelessly, even if it took thousands of years, even if the rest of humanity went its own way in the meantime—even if the rest of humanity agreed that the Law only led to the knowledge of sin.

Eyes opened by this new reading, Halkin sees even further. Against his own dislike of being told what to do and his desire “to do the right thing because I wanted to, not because I had to,” he acknowledges that most people cannot do without the Law:

There isn’t enough of mankind—there isn’t enough of me—that having no Law, will do by nature the thing contained in the Law. . . . If it’s taken me most of a lifetime to realize that, then that’s what lifetimes must be for.

The essay ends with Halkin celebrating, along with the chastened Israelites, their building of the Tabernacle. As if present in their midst, he is astonished when, the building complete, a “cloud covered the Tent of Meeting and the glory of God filled the Tabernacle.”

God is back. It’s a mini-Sinai, His glory in cloud is like fire in smoke. All that light and dark mixed together, the brightest sunshine and the blackest gloom! . . .

Bring on Leviticus!

The Book faithfully read—not just as literature—has produced another convert to its wisdom. Things are falling into place.

Making meaning of a life—and of what one’s lifetime was for—is the tacit subject of the last (and last written) essay, “Working One’s Way Out” (2021). As already noted, it is a highly personal and celebratory review of a memoir, posthumously published, by Halkin’s graduate-school friend, Steve Kogan. Both for reviewer Halkin as for author Kogan, loss and nostalgia are ubiquitous, as both relive what the world was like when they (and I) were young, finding in the comparison with life today an indictment of the present. Yet the nostalgic but honest reviewer confesses proper suspicions of the judgments made by nostalgia, especially by people our age:

One of the challenges of growing old is the need to distinguish between nostalgia and valid social criticism. One doesn’t want to be a grouchy old man. Things may seem to have been better when we were young—but were they better because they were better, or were they better because we were young?

His own warning notwithstanding, Halkin manages to sort things out, precisely around the issue of his Jewishness.

When he was young, he like Kogan and many of their friends, made very little of their Jewishness, and none of them knew just how Jewish the other ones were. The reason was, again, a variant of either/or, Jew or American.

It wasn’t that we were embarrassed by our Jewishness or went out of our way to hide it. We just didn’t know what to do with it or where to put it. It had no obvious relation to the Americans we were or wanted to be or to that “all-embracing and positive vision of America,” as Kogan puts it, that “flowed from the spirit of Whitman’s poetry.”

But the Whitmanesque vision of “One Identity” was soon to be exposed as myth, ironically as a result of the civil-rights movement undertaken to fulfill it. The project for an integrated America, undivided by race or class, a project that attracted young Jewish idealists like Kogan and Halkin (and me), collapsed in the face of the Watts riots and the rise of the separatist black-power movement.

Halkin read the tea leaves better than I did.

In my relationship to America, as in America itself, that year [1965] was a turning point. I didn’t want to be a voyeur. I had my own people, just as Black Americans had theirs. The myth of Whitman’s America was falling apart for me, falling apart for us all.

National myths can be dangerous, but they are what make a nation a nation and not just the conglomeration of its citizens that America has since become. It never found anything to replace Whitman with.

Five years later, Halkin moved to Israel, to join his own people—to live, love, write, and flourish as the Jew he is, in his homeland. He had figured out where to “put” his Jewishness.

The Nature of Halkin’s Jewishness

What, at last, can we say about the nature of Halkin’s Jewishness, as it appears in these essays? What, despite the twists and turns of the complications, is its enduring essence? What is Jewishly at work in the man who searches for his roots in the shtetl; regrets his loss of faith in the Jewish God but keeps faith with his own Jewishness; embraces the best of Hebrew and Yiddish literature and feels solidarity with klal Yisra’el, the community of Israel; leaves the land of his birth to join his people, planting new roots in the true home of his ancestors; feels the presence of their ghosts who walk the land; bemoans the split between Judaism and humanism; defends the tradition against misappropriation, while seeking to preserve it by friendly addition; and who recognizes, against his own inclinations, the wisdom of Torah as law, not merely its beauty as literature?

In response to these questions, a few things stand out.

First, Halkin is a man of deep longings, what the Greeks called eros. But the ultimate object of his longings is not, as it was among the Greeks, some disembodied Idea of the Good or otherworldly Isles of the Blest, but the fulfillment, here and now, of the life he has been given, as a Jewish human being. The nostalgia that suffuses these essays is finally not a desire to return to the past as past, or even to recapture his innocent youth of yesteryear. The homecoming (nostos) Halkin yearns for is always ahead of him: a wholeness of soul, a life lived with loved ones and fellow Jews, a life keeping faith with one’s ancestors and one’s origins through active remembrance and the religion of the “living dead,” a life informed by humanist beauty and goodness, to be sure, but also by the wisdom and humanity of the Jewish tradition, a tradition kept young for him by embracing it as precious.

Second, Halkin is a man of fidelity. For all his independence, resistance to authority, and distance from halakhic observance, Halkin is at bottom a loyal and faithful exponent of Jewish learning and tradition. Against the noise and vapidity of modern life and against the politicized “surrogate-womb” distortions of Jewish thought, Halkin has devoted himself to keeping alive the best of Jewish texts and authors. Refusing the either/or of “religious prig” or “ignoramus,” he is recognizably the heir of his Uncle Simon, even surpassing him in keeping the faith: despite his own disappointments and disillusionments, Hillel Halkin never would, out of despair, imagine moving to North Dakota and living as a Red Indian. For he has, in fact, managed in his own life and work to fulfill the original Zionist dream: “to combine a commitment to the modern world and its highest ideals with an allegiance, if not to the ritual forms, at least to the great texts and memories, of Jewish tradition and their resonance in the physical landscape of Israel.”

Third, Halkin builds out from his inheritance. In keeping with the developmental character of the Jewish thought, Halkin practices his allegiance to the tradition by revitalizing it, adding to what he has inherited. In most of these essays, we find Halkin meeting the challenges of the present moment with tales of the Jewish past at his side, and he gives those tales new salience by the company they now keep in his life. As he put it: “although nothing can be restored, everything that has happened can be changed by adding to it, so that the past is always with us and continually still taking place (emphasis added).”

Fourth, Halkin drinks “l’ḥayyim” to life, to love, and to language. He has lived passionately and fully, with grateful appreciation of the astonishing existence of human life and thought and the glorious existence of the world. He may be skeptical about the story of creation in Genesis 1, but in his speech, thought, and creativity he pays homage to its teaching that man alone among the creatures is b’tselem elohim, in the image of God, most especially in man’s speech, thought, and creativity.

Fifth, personally, Halkin has an exquisite capacity for self-reflection and self-evaluation. We do not see him beating his breast during the al Ḥet on Yom Kippur, but he conducts before our eyes a subtle ḥeshbon ha-nefesh, a Jewishly freighted stock-taking of one’s life, conducted to be sure with self-irony and humor, but always calling a failing a failing. The very attempt to make sense of one’s life—to put everything in its place—reflects Judaism’s revolutionary view that we must answer for our lives, not only before the imagined bar of judgment but also here and now. A Jew must always be prepared to give an account of how he or she has used the unmerited gifts of life and lifetime. In this essaying autobiography, Halkin has met that obligation in full.

Finally, Hillel Halkin is given to speaking truthfully, both about himself and about his subjects. He uses language with precision and care, seeking always to clarify, to vivify, to reveal what has been ignored or overlooked. He has an aversion to cant, jargon, pomposity, and falsehood. Although acutely self-conscious and not self-effacing, his writing is anything but self-indulgent or self-justifying. Although he is not shy about voicing his opinions, he is scrupulously fair in assessing the words and deeds of others (and of himself), eager always to get it right. He takes no one’s name in vain. He prefers the living truth of stories to the abstract truth of argument; the stories of his own experiences are seamlessly interwoven with his observations about the world around him. In all these ways, he is a faithful son of Torah and talmudic teaching and learning. A priest is frum, Hillel Halkin is erlikh.

But wait, what about Hillel Halkin and God? Surely, ritually observant or not, a Jew worthy of the name cannot be an atheist. And Halkin early on reports, with sadness, his loss of faith in the Jewish God. But that occurred long ago, in high school. What, in the course of a lifetime presented in these essays, does the mature Halkin think about God? Will he say, with Irving Kristol, that he believes in the Jewish people and the Jewish people believe in God? Or will he say, as Irving Kristol also said of himself, that he is “non-observant Orthodox,” “theotropic,” oriented toward the divine, “impossible to become non-religious”? How should we take the end of his essay on “Law in the Desert,” when he celebrates with the Israelites, seeing the divine light in the darkness over the Tabernacle?

It is hard to say, for on this subject alone Halkin has not been forthcoming. But any answer will depend on the prior question, not about the existence of God but about the “being” or “nature” of God, who “exists” or “doesn’t.” I rather suspect that the God in whom young Halkin lost faith was a youthful misconception, an easy target for skeptical rationalism, especially when one approaches the question of God not through lived experience and human longing but through the abstracted categories of philosophy and modern science. Has he perhaps acquired a more mature notion of or approach to the deity? And if not, might he still be able to acquire one? Or should we perhaps say, better, that for a Jew it is possible to live a God-seeking and a God-honoring life—as an erlikher Yid—without bothering oneself about theology? I wonder how Halkin would answer this question.

Either/Or

In the essay “Either/Or,” Hillel Halkin emphasizes the fact that his generation was raised to believe that life demands mutually exclusive, binary choices on matters such as God or not, Jew or American, religious or humanist. But as these essays and his other books make clear, Halkin’s overall life and thought in fact broke free of those straightjacketing alternatives. He lived in his maturity, as he writes in his essays, more “both/and” than “either/or.” In this respect, he may be not the last of a dying breed, but the herald of a new day.

In his wonderful new book The Wondering Jew, Micah Goodman speaks hopefully about several emerging new movements in Israel that can reconstitute a middle, “both/and,” between the extremes of rebellious secularism and dogmatic religiosity: on the one side, alternative Jewish secularisms, on the other side, alternative flexible religiosities. The first are seeking and gaining connection, the second are seeking and gaining openness. For these encouraging new movements, on both sides of a narrowing divide, not only his essays but the collected writings of Hillel Halkin should be required reading.

But, alas, Halkin, though widely admired in the Anglosphere and though surely deserving of the Israel Prize for his writings, is today largely a prophet without honor in the Jewish homeland. The reason, ironically, is linguistic: Hillel Halkin writes in English.

The remedy is simple. Let’s get him translated into Hebrew. His time is coming.

More about: Arts & Culture, Hillel Halkin, Israel & Zionism, Literature