This essay is the first in a six-part series by Jacob Howland on Homer and the Hebrew Bible. Historians of Western intellectual culture sometimes compare “Jerusalem,” or the biblical traditions that erupt into history at Sinai, with “Athens,” the city where Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle sought human wisdom through the exercise of the human mind. In this series, Howland invites a different comparison. Rather than comparing later prophets to philosophers, he looks back at yet earlier cultural cornerstones set at the very foundations of Hebraic and Greek civilizations. Future installments in Howland’s series will arrive monthly. —The Editors

The encounter between Jews and Greeks has not always been a happy one—to say the least. The holiday of Hanukkah famously recalls the series of events that began with the 168 BCE seizure of Jerusalem by the forces of the Syrian-Greek ruler Antiochus IV. “Raging like a wild animal,” according to the book of Maccabees, Antiochus proceeded to massacre or enslave thousands of citizens, to make the practice of circumcision a capital crime, to order the worship of Zeus as supreme god, and to sacrifice pigs in the Temple. Four years later, a revolt led by the heroic Maccabees managed to retake the city, to purify and re-dedicate the Temple, and to rekindle its lights.

But as much as Hanukkah is the story of a Jewish nationalist uprising against Greek domination and religious oppression, it is also the story of an internal conflict between Jewish traditionalists like the Maccabee family and assimilationist Jewish “Hellenizers.” As time went on, that internal conflict would only grow in intensity, to the point where, centuries later, the rabbis of the Talmud would record a saying: “Cursed is he who raises pigs, and cursed is he who teaches his son Greek wisdom” (M’naḥot 64b).

That term, “Greek wisdom,” referred to much more than pagan idolatry and its corruptive effects on Jewish life. In the form of science and philosophy, indeed, the loftier parts of “Greek wisdom” found a receptive audience among major Jewish thinkers in antiquity and later. The claim by Philo of Alexandria (ca. 20 BCE-50 CE) that Moses was the teacher of the Greek philosophers did honor to both parties. A millennium later, Maimonides (1138-1204) would be heavily influenced by the Aristotelian ideas of the Islamic philosopher al-Farabi. More generally, the creative tension between “Hebraism and Hellenism” (in the coinage of the 19th-century English poet Matthew Arnold) or “Jerusalem and Athens” (as the 20th-century political philosopher Leo Strauss put it)—that is, between particular revelation and universal reason, between trust in the Lord and trust in the intellect—has long energized the spiritual and intellectual life of the West.

Still, neither rabbinic Judaism nor Greek philosophy sprang out of nowhere; their deepest roots extended to even more remote antiquity. The earliest oral traditions incorporated into the Bible preceded the talmudic rabbis by more than a millennium, while the Greek bard Homer, drawing on primeval legends, composed the Iliad and the Odyssey centuries before Plato and Aristotle would come along to study and laud him, and even longer before Antiochus would provoke the Maccabean revolt in the land of Israel.

The Hebrew Bible and Homer’s epics were first not only in time but also in importance. No works have ever proved more potent, or more fertile, across the entire field of human life and culture. “Turn it and turn it, for everything is in it,” the talmudic sage Ben Bag-Bag said of the Torah; “reflect on it and grow old and gray with it.” Aeschylus, the first and greatest Athenian dramatist, called his compositions “scraps from the banquet of Homer,” while the Roman rhetorician Quintilian spoke for all of classical antiquity when he described Homer as “the father of tragedy and comedy and of all accomplishment in letters.”

Does this mean that Jews should read Homer? The tension between them might seem to weigh against any such suggestion. The people of Israel are divinely ordained, Isaiah teaches, to be a “light unto the nations, that My salvation may be unto the ends of the earth.” If the nations are in darkness, what is to be gained by spending time with their literature?

An answer is given in the Talmud. Asked by his nephew, “May one such as I who has studied the whole of the Torah learn Greek wisdom?” Rabbi Yishmael recited the verse “This book of the Law shall not depart out of thy mouth, but thou shalt meditate therein day and night” (Joshua 1:8). “Go,” the rabbi told his interlocutor, “and search for an hour that is neither part of the day nor part of the night, and learn Greek wisdom in it” (M’naḥot 99b).

Clear enough. Or could Rabbi Yishmael’s words possibly be ambiguous? Since such an hour can indeed be found in the minutes between dawn and sunrise and between sunset and dusk, was he suggesting that the Greeks were neither in darkness nor in light but somewhere in between, in twilight? Did he mean to forbid the study of their wisdom or, within narrow limits, to permit it?

These questions invite two others: What does it mean to think like a Greek or a Jew? And what does it mean to read Homer or the Bible? After all, it was through questioning and wrestling with these texts, and persistently contending with their resistance to easy interpretation, that Aeschylus learned to think like a Greek and Rabbi Yishmael like a Jew. Unfortunately, the likelihood of such encounters has been drastically reduced by the shared fate of ancient letters in the modern age.

Precisely when this age began is a subject of scholarly debate, but in science the inaugural event was the publication in 1543 of a book, On Revolutions, by the Polish astronomer Copernicus. Decisively refuting the geocentric system of Ptolemy, embraced since antiquity, Copernicus showed that the sun and the stars do not orbit the earth; rather, the earth orbits the sun and rotates on its axis, causing the apparent motion of the stars.

Copernicus’s theory was publicly endorsed by the astronomer Galileo, who was tried and condemned for this heterodox opinion by the Roman Catholic Inquisition. Science aside, the Inquisitors correctly grasped that Copernicus’s heliocentric theory posed a grave danger to the authority of the Church, which favored the geocentric theory because it harmonized with the Bible. And the danger was not only to the Church but to the whole field of thought and belief as taught in the schools and universities of Europe.

After Copernicus, it was no longer possible simply to accept on authority—to take the word of—any book, be it the book, the Bible, or Aristotle’s Physics. In thus undermining textual authority, the Copernican revolution also prepared the ground for the critical “deconstruction” of books and authors that were once regarded as classic—that is, as exemplary and superior.

The first great modern deconstruction of an ancient text was Benedict Spinoza’s Theological-Political Treatise (1670). There Spinoza argued that Moses was not the author of the Five Books of Moses and that the Hebrew Bible consisted of various texts composed by multiple unknown authors over many centuries.

These views worked to dispel the atmosphere of sanctity that once enveloped the Hebrew Bible, and so took the first step along a path that in the fullness of time has led to the ignorance of and disdain for Scripture that are common features of life in the West today. The same critical approach was eventually applied to the New Testament. And, in time, classicists inspired by the rigor and precision of the natural sciences came to shift their own focus from Homer’s teaching about the human condition and instead to approach his epic poems as patchworks woven of folksongs instinctually improvised by illiterate bards.

The study of classic texts is called philology, a Greek construction that means “love of words.” Properly speaking, such study aims to understand a text as an integrated whole. But the scientific and historical disintegration of the classics, activities that presuppose and promote a certain irreverence toward texts once held sacred, undermines that labor of love. Cut and dried by criticism—including the insipid hermeneutical strategies that today go by the name of “critical theory”—the Homeric epics and the Bible are rendered lifeless. Their uniquely strange and alluring voices, which for ages inspired humane words, thoughts, deeds, and artistic productions in every medium, are muffled if not rendered inaudible.

If we are to read Homer and the Bible as they want to be read, we must therefore step behind the scrim of modern distortions and relate to them not as moderns but as pre-moderns. The word “author,” auctor in Latin, comes from augere, “to make to grow, to originate, promote, increase.” In the root sense of the term, Homer and the Bible wield authority as sources of human understanding and creativity. Can we still experience that life-giving potency? The short answer is yes, but a reader’s access to it depends on a high degree of attentiveness and generosity.

For starters, then, let’s try two passages, one from the Odyssey and one from Genesis. In the first passage, the Greek hero Menelaus wrestles with the sea-god Proteus; in the second, the Hebrew patriarch Jacob wrestles with a mysterious “man.” In these two episodes, we encounter both the strange nature of the Homeric and biblical texts and the dense and mysterious realities that, however incompletely, shine forth from them. (Quotations from the Odyssey are drawn, with occasional emendations, from the translation by Robert Fagles; quotations from the Hebrew Bible are drawn from the translation by Robert Alter.)

The Odyssey is the story of an agonizingly prolonged homecoming, the pain of which is experienced by Odysseus, the brilliant and cunning hero of the Trojan war, as acute nostalgia (from Greek nostos, homecoming, and algos, pain). In the epic’s first books, Odysseus’s son Telemachus, roused to action by the goddess Athena, sails from the ancestral home in Ithaca to the Peloponnesus searching for news of his father, last seen pushing off from the plundered ruins of Troy ten years earlier.

Telemachus visits two great warriors who were at Troy with Odysseus: first Nestor in Pylos and then Menelaus in Sparta, now reunited with his wife Helen. In the latter’s palace, Telemachus confesses to being struck with awe at its “unspeakable wealth”—wrought bronze, gold, and silver; carved ivory and amber. Menelaus explains that he had gathered the treasure for eight years in Libya and Egypt, where he had been swept by wind and current after leaving Troy, a thousand kilometers north on the Aegean seacoast.

“Many things I suffered and much I wandered,” Menelaus tells Telemachus. After finishing his business in Libya and Egypt, he was marooned on the island of Pharos near the Nile delta, where “the gods becalmed me twenty days” with “not a breath of the breezes ruffling out to sea/ that speed a ship across the ocean’s broad back.” Here Homer echoes his identification of Odysseus alone as the man who had “suffered many pains” and “wandered many ways” and then implicitly sets Menelaus’s twenty-day stay on Pharos against Odysseus’s twenty years away from home—thereby making it clear that the former’s odyssey was a microcosm of the latter’s.

And there is more along the same lines. Facing starvation, Menelaus and his men are saved by the “glistening goddess” Eidothea, the daughter of Proteus: the immortal “Old Man of the Sea who never lies,/ who sounds the deep in all its depths.” It is Proteus, Eidothea tells Menelaus, who holds the keys to his return:

He’s my father, they say, he gave me life. And he,

if only you ambush him somehow and pin him down,

will tell you the way to go, the stages of your voyage,

how you can cross the swarming sea and reach home at last.

In Greek myth, gods are generally grudging, not provident. To get what he needs from Proteus, Menelaus must use craft and force. Eidothea explains that the highly mutable Proteus will speak only when he wearies of transforming himself into various animals and elements. Menelaus must not only seize him but hold on for dear life.

But Proteus is not just ancient but archaic. Proteuō means “to be first.” Like his element the ever-changing sea—a vestige of primeval chaos—Proteus somehow embodies the fathomless origin of all things; like other immortals in the Iliad and the Odyssey, he is visible only in his unstable looks or appearances. His shape-shifting productivity is the definitive quality of nature or phusis, a word derived from the verb phuō: “to sprout, bring forth, grow.” Only by imitating the primordial, transformative energy of nature—in this case, by disguising himself and three of his comrades in the flayed skins of seals—can Menelaus hope to surprise Proteus and make him speak.

The sealskins were Eidothea’s idea. Every day at high noon, she confides, Proteus comes up from the deep for a nap with his rookery of seals. So Menelaus and his men in their flayed hides bed down among these creatures, who, Menelaus explains to his guest, would have overpowered them by their stench had not the goddess “sped to our rescue, found the cure/ with ambrosia, daubing it under each man’s nose.” After Proteus lies down to sleep, they rush and cling to him while he turns into “a great bearded lion/ and then a serpent—a panther—a ramping wild boar—/ a torrent of water—a tree with soaring branches.”

This has the ring of symbolism. In his epics, Homer himself becomes all things, takes on all shapes. Ambrosia literally means “immortal stuff.” Just as Menelaus can still smell “the awful reek of all those sea-fed brutes” but is not overcome by it, we can smell it, too, through the ambrosia of Homeric imagination.

Thus does Menelaus’s little odyssey turn out to be about reading the Odyssey. If we cling to his text, Homer suggests, holding fast through all of its transformations, it might finally speak its deepest word. It might reveal how to return to light and life, which is the only cure for nostalgia: itself a sickness of soul to which today’s readers, uprooted by modernity from organic traditions and societies, and increasingly pressed to repudiate them, are especially prone.

Odysseus is a man of many twists and turns: strong, clever moves that leverage all of his powers, mental and physical. He is a far greater wrestler than Menelaus. And his character is as broad as his wide shoulders: at once savage and gentle, reckless and prudent.

Jacob, too, is a wrestler, as strong, spirited, and internally capacious as Odysseus, and sometimes as underhanded. At birth, the younger of twin boys, he announces himself immediately by grabbing his brother Esau’s heel as the two emerge from the womb, a gesture that earns him his name Ya‘aqob, from ‘aqob, “crooked,” and ‘aqeb, “heel.” Later, exploiting his elder brother’s famished weakness, he gets Esau to cede his birthright for a bowl of stew; later still, he apes his brother’s hairy body and gamey odor in order to steal from their aged and blind father Isaac the blessing meant for the favored elder son.

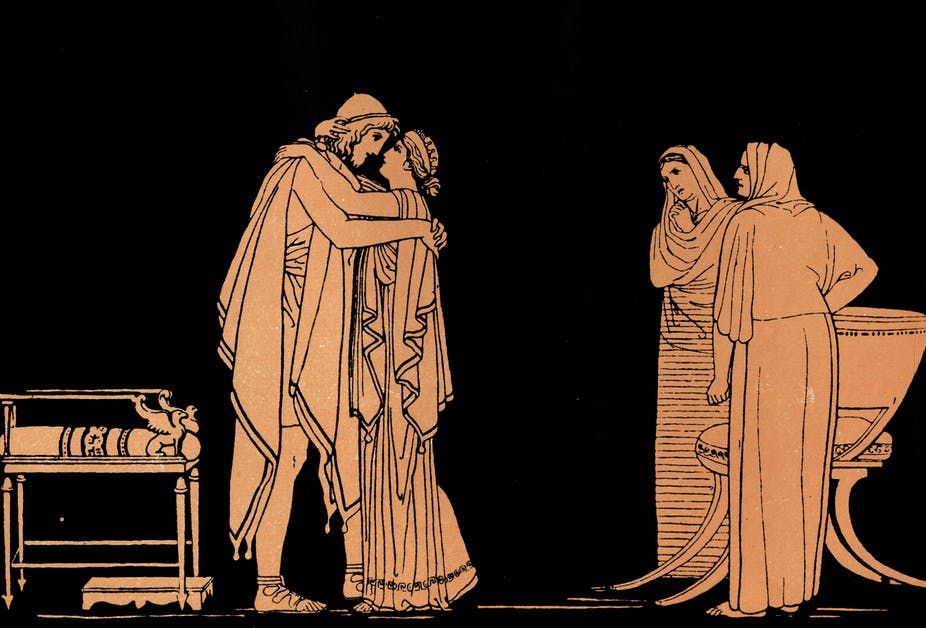

Twenty years after fleeing to his uncle Laban in Haran, undertaken at his mother Rebecca’s urging, Jacob has an experience that rivals Menelaus’s encounter with Proteus. It occurs on his return to Canaan, during the long and anxious night before his fateful reunion with Esau, now a powerful chieftain who is just then approaching with 400 men—a standard number (as Robert Alter notes) for a war party. The unfinished business between the two now also stands between Jacob and the land God had promised to him two decades earlier as he slept at Bethel and dreamed of angels ascending and descending a ladder to heaven.

And [Jacob] rose on that night and took his two wives and his two concubines and his eleven boys and he crossed over the Jabbok ford. And he took them and brought them across the stream, and he brought across all that he had. And Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until the break of dawn. And he saw that he had not won out against him and he touched his hip socket and Jacob’s hip socket was wrenched as he wrestled with him. And he said, “Let me go, for dawn is breaking.” And he said, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” And he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” And he said, “Not Jacob shall your name hence be said, but Israel, for you have striven with God and men, and won out.” And Jacob asked and said, “Tell your name, pray.” And he said, “Why should you ask my name?” and there he blessed him.

The text is as opaque and portentous as a dream. Who is the anonymous “man”—a double so well matched with Jacob that they fight to a draw? Why do they contend with each other? “And he saw that he had not won out against him and he touched his hip socket”: the very language flips around so that we cannot tell who is who, and even the name given to him by the man is ambiguous. He calls him Israel, “for you have striven with God and men and won out”; but Alter notes that Yisra’el, “he strives with God,” might also mean “God will rule” or “God will prevail.”

Some things are clear enough, however. If Menelaus wrestles the sea-god at noon, a time of maximum visibility, Jacob comes to grips with his strange double when the black of night veils all appearances. More importantly, Menelaus wears a disguise and has three strong sidekicks to help him in the struggle with Proteus, but Jacob is alone, raw with fear and guilt, and with nowhere to hide when the mysterious man appears. “Odyssean” strength and cunning have gotten him where he is, but what characterizes him in this encounter with the divine is his great moral vulnerability—a vulnerability underscored by the crippling wound to his hip socket sustained in the struggle.

Yet even in his pain, he will not release the man until he is blessed. What does this mean? A psychological interpretation confirms our sense that the mysterious man is something more than human—some haunting spiritual power. On this reading, the man is on one level a figuration of Esau, whose blessing Jacob needs if he is to let go of the guilt and fear he incurred when he wronged him. No less important, Esau’s blessing, which in the sequel Esau does deliver, will allow him finally to let go of his own anger toward Jacob.

Only moral boldness can dispel the fratricidal curses that hang over both men, the feelings toward each other that harm and undermine them. Jacob will go forth healed in soul, if also limping like a wounded warrior. And Jacob is a hero—a distinctly Israelite one, whose victories are achieved not (or not simply) on the battlefield but in the realm of the spirit.

Jacob thus looks to the future in a way that Menelaus does not. That Greek hero grapples with Proteus so that he may learn how to get back home, while Jacob insists on hearing the word of blessing that will allow him to go forward. This fundamental difference points toward the metaphysical and spiritual gulf that separates Genesis from the Odyssey.

The first thing in Homer is nature, while the first thing in the Bible is God, the “source of living waters” and the author of nature itself. And God’s authority or agency is manifested also in the linear, goal-directed process of history: a concept foreign to the Greeks. Nature is cyclical or repetitive—Menelaus speaks of “the circling year”—but history, forged in the interaction of God and man, advances along an untrodden path.

There is nevertheless a deep commonality that binds Jacob’s night at the Jabbok with Menelaus’s days on Pharos. These come together in the middle ground of something like Rabbi Yishmael’s twilight. For Jacob’s wrestling, too, seems to be an allegory of reading. Jacob is called Israel, but so are the people of the Book, the people who paradoxically strive with God so that God may prevail. They do so in the first instance by coming to grips with the Bible, the God of which hides His face and will not be named but speaks to those who are ready to hear. That would also be those who tenaciously struggle with the text; who open themselves to being transformed, even wounded by it; and who boldly demand its blessings even though—or perhaps just because—the fullness of its meaning will always exceed their grasp.

Homer’s Odyssey and Genesis are tales of wanderers, people who struggle to find, make, or keep a home in the world. Both draw from a common ancient stock of characters, myths, and literary motifs: wily tricksters, powerful women, heroic men, mortals mating with immortals, naming and renaming, rites of initiation, clothing, nakedness, intoxication; the list is by no means exhaustive. Both illuminate the enduring questions of human life, including how to bring order and common purpose to the otherwise chaotic relationships between men and women, fathers and sons, familiars and strangers, clans and nations. Both transmit precious wisdom accumulated through long experience and much suffering.

I believe these are sufficient reasons for Jews to read Homer. And yet, despite these deep and extensive similarities, few scholars have thought to put together the stories of Genesis and the Odyssey so that they might illuminate one another. The time is ripe for such an undertaking, not least because what the late Roger Scruton called “the culture of repudiation” now poses a grave threat to the preservation and transmission of the Western tradition. As our own age is a self-imposed exile of radical forgetting, so our posterity depends on recovering the vital and generative wisdom of our ancestors.

The Odyssey begins in the middle of things, with a civilization in decline and Odysseus languishing as a prisoner on the island of the predatory nymph Calypso. Genesis has a clearer pedagogical structure. It begins at the beginning, with the earliest men and women learning through trial and error what being human requires of them, and its major divisions—Creation to the expulsion from Eden; Cain and Abel to the Flood; Noah and his sons to Babel; the stories of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph and his brothers—build on one another, progressively deepening and broadening our understanding of the fundamental issues.

We, too, shall begin at the beginning and follow the biblical order in thinking through the universal and patriarchal histories of Genesis alongside the Odyssey. The next essay in this series explores the Greek and biblical stories of human origins and the emerging relationships between mortals and immortals, husbands and wives, parents and children.

More about: Arts & Culture, Hebrew Bible, History & Ideas, Homer, Spinoza