It’s not easy following the Torah reading from a 13th-century manuscript. The marginal drolleries—little decorated images—can be distracting, and the Masoretic notes and annotations persist in twisting themselves into interesting geometric (and other) forms. The Hebrew cursive for the Rashi commentary is impossible to parse, looking for all the world like a series of identical brushstrokes. And the text itself is compressed, quirky, hedged about with a thicket of vowels and cantillation marks intended to ease reading but in fact further cramping the already tightly-spaced text column. And how in the world is one to even see the tiny marks that indicate the ends of sections and readings? And yet following the Torah portion from a late-13th-century manuscript was precisely what I was doing one recent Saturday morning when a mystery appeared.

The manuscript in question is known as the Rothschild Pentateuch, a very exciting and relatively recent acquisition of the J. Paul Getty Museum and Research Center in Los Angeles. The Rothschild is a relatively little-studied manuscript, and I’m truly honored I was asked to participate with a group of other scholars in a seminar introducing it to the scholarly community last week. My mandate was to speak about the menagerie of illustrated creatures present in this Pentateuch. To help us prepare for the seminar, the Getty had sent each participant a complete set of scans of the manuscript on a thumb drive.

The Rothschild Pentateuch contains the Five Books of Moses divided for liturgical reading in the synagogue, followed by the liturgical prophetic readings, plus notes on the text and a commentary by the famous medieval French exegete Rashi. The codex was written in 1296 in what was then known as Ashkenaz—present-day northern France and western Germany—for the patron Joseph ben Joseph Martel, whom textual clues indicate was probably a refugee forced to flee England during the expulsion of 1290. The scribes were Eliyahu ben Meshulum, who did the main text, and Eliyahu ben Yeḥiel, who handled the micrography. The illuminator of the lively, beast-filled illustrations is unknown, though a missing leaf was replaced in the second half of the 15th century.

In the 700 years since it was written, the Rothschild codex has had quite a journey. Inscriptions in the manuscript indicate that it was passed down through the hands of many Ashkenazic communal luminaries, including Rabbi Akiva ben Ephraim before 1484. It was long in the hands of the Katzenellenbogen family—a family of noted rabbis, among them Saul Wahl Katzenellenbogen, putative “king of Poland for a single day,” and the ancestors of the likes of Martin Buber and Karl Marx—until it was acquired by Baroness Adelaide Rothschild (1853-1934), who donated it to a German state library in 1920. Thirty years later, the manuscript was part of an exchange for real estate between the German government and a German-Jewish family that had relocated to New York. From then, it resided with that family until it was sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2018. And now it’s with me—sort of.

The digital experience of a historical manuscript turns out to be strange—not as good as the real thing, but still helpful. My preferred method of working on manuscripts is to sit in front of them, to feel the parchment, experiencing it as the skin it is, to take in the play of light on the illumination, to be able to see underpainting and silverpointing, the preparations, corrections, abrasions and imperfections, and to experience even the particular scent of each volume. Barring such first-hand experience, the digital “gift” was the next best thing. So I printed out all of the thousand or so folia, and bound them form as close a surrogate of the original as I could manage.

When you hold a bound life-sized codex in your hand, even a facsimile as cheap as the one I patched together, you get a profound sense of the heft and the character of the volume, how it feels in the hands. (If it can be held in the hands—a thousand folia turns out to push that limit.) You see how the designs of the marginalia and the illuminations relate to each other over each open set of pages. You realize that the pictures are speaking to one another or pointing at, or to one another or at loci in the text. The layout, the format, the stops, the divisions begin to make sense. The thing comes together as the book it was intended to be rather than as pixels and single pages on a screen.

To review such a massive codex systematically, I could sit with it at my desk, in the library, and so on, but as I fiddled with it I realized there was a natural opportunity for me to integrate my work into my home life. My family and I hold synagogue services in our living room each week, and so I resolved that, as the Torah portion is read, I would follow in the Rothschild Pentateuch rather than following along in my printed Bible. I have been doing so for several months now.

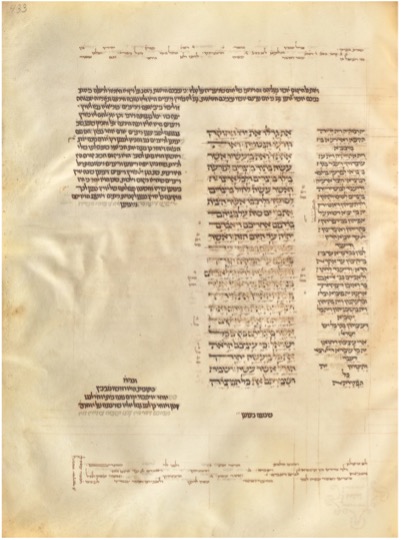

How has it gone? Once one becomes used over time to negotiating the crampedness of the script and the thicket of vowels and cantillation signs, the actual text of the Pentateuch on the whole is remarkably legible. The page is still generally bright and the letters still dark, though there are several places in which these have faded slightly, as one might expect in a manuscript that turned 725 a short while ago. At least that’s what I thought, until, as I read through week after week, I discovered one section of the text, about five centimeters tall, that has become almost totally illegible. It is faded in a manner unique in the entire manuscript. And herein lies our mystery.

That text is the Torah portion Eikev (Deuteronomy 7:12–11:25) and the passage is a specific one. Moses, in one of his final orations before his passing, is admonishing the Israelites that they must observe God’s commandments or suffer a terrible fate. In order to make his point. Moses recalls a disturbing case of rebellion and how it was punished. Recall, Moses states, “what [God] did to Datan and Aviram, sons of Eliav son of Reuben, when the earth opened her mouth and swallowed them, along with their households, their tents, and every living thing in their train, from amidst all Israel.” Here, in the total destruction of the rebels and their property, is an explicit threat of the consequences for rebellion.

Seeing the exceptionally faded script at this passage, I wondered why its lines specifically were so nearly erased. Did they contain an error that needed elimination? No. One can read the outlines of what remains, and it is correct. Was the text censored? If it was, there should be some telltale indication—the scrape of a penknife, ink applied over the text—and there is not. This is not a natural light fading (as one finds in many places in the manuscript), nor is it an erasure. It is an extreme fading due to some sort of abrasion or contact with something that literally dissolved the ink. There is no sign of damage on the opposite folio or on the other side of the folio, but there is a slight warping in the left margin of this folio itself, stress lines marking the parchment as pulling towards the text, towards the gutter, as if something a bit weighty had been placed upon this text. The erased section is about three fingers wide, if I place my average-sized hand on the page.

I puzzled for a while over this erasure. And then I recalled a terrible and disturbing text I have taught for years, the famous oath “according to the Jewish custom” (more judaico) that was required of Jews testifying in Gentile courts, since at least the time of the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII (912-959). The earliest version of this oath from that time demands that a Jew should have a girdle of thorns around his loins, stand in water, and swear by “Barase Baraa”—Breshit bara, the first words of Genesis—so that if he speaks untruth “the earth may swallow him as it did Datan and Aviram.” The historian Jacob Rader Marcus, in his The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315-1791, says that “this Byzantine formula, which is probably based on a Hebrew or Aramaic original, was employed, with considerable variations, in most European lands during the Middle Ages.” He cites a variation from 1392 in Germany. The Jewish litigant or witness, subjected to various physical indignities and humiliations, is made to “stand on a sow’s skin and the five books of Master Moses shall lie before him, and his right hand up to the wrist shall lie on the book and he shall repeat after him who administers the oath of the Jews.” In that oath, first among the listed curses for perjury, we read again, “May the earth envelope and swallow you up as it did Datan and Aviram. And may your dust never join other dust, and your earth never join other earth in the bosom of Master Abraham if what you say is not true and right.” In other words, you’ll be swallowed up and will never get a decent burial, much less be resurrected. To seal the humiliation and further intimidate, in some versions of the oath Jews were made to do things like pronounce the ineffable name of God.

Recalling this text, I suddenly realized what I was looking at in the Rothschild Pentateuch. This codex, the prize possession of the wealthy g’virim (heads and patrons) of the community, must have been the actual copy of “the five books of Master Moses” that was brought to court and sworn upon on numerous occasions by Jewish litigants or witnesses. It was their “right hands up to the wrist” and their no-doubt-perspiring fingers that dissolved the text and pulled the parchment down on the folio containing the references to Datan and Aviram. As I say, there is about three fingers width of text here—perhaps the Jewish litigants or witnesses were required to use three fingers to swear, as Christians did, further humiliating the Jews into performing a symbolic evocation of the Trinity. There are also descriptions of the oath which require that the doorknob or lock of the synagogue be placed on the open Pentateuch. I had a strong hunch that had we the proper technology the dissolved text would prove to have traces of reaction to chemicals in human perspiration. And so I reached out to Beth Morrison, Getty’s senior curator of manuscripts, who in turn consulted Nancy Turner, the head of the Paper Conservation Department and Getty’s specialist in parchment.

Nancy reported back as follows:

I looked at fol. 433v. Regarding the center right column of text about which he speaks, indeed the text appears to be abraded in one area. And I can’t see any erasure or re-writing in that area at center right. So: abrasion with no re-writing. Confirming his observation. I also think that—although there are many places where the text is light—there is no other passage in the ms. that occasions this kind of abrasion or dissolution.

Meanwhile, Beth Morrison herself reports that she noticed

that the folio along the edge is more transparent in two places along the left edge, a possible indication of more handling in those areas because of the oils in one’s hands. We compared those areas to numerous other folios in the manuscript and they were noticeably more translucent. In addition, the parchment was worn very smooth in those two areas, again indicating handling over time.

Everyone agreed that there seems to have been something actually and deliberately erased in the inner margin, but that it will require additional scrutiny to determine what it was. I’m just thinking aloud here, but perhaps it was a marginal note indicating that this was the passage on which the hand (or synagogue lock or doorknob) was supposed to be placed while testimony was given, and it was erased later, effectively to bury the memory of the trauma of the “Jewish oath.”

Like the wine-stains in some of my favorite haggadot, this trace of the touch of human hands, on this beautiful manuscript made me both sad and joyful. These were not the hands of Jews at a celebratory feast of freedom, but the hands of Jews under terrible duress, so I was sad, of course, for their humiliation and their fate. But I was, at the same time, joyful because the beautiful book has survived as a mute witness to their testimony, their trust in God, and their bravery in terrible circumstances.

More about: Arts & Culture, Hebrew Bible, Religion & Holidays