From the Hebrew Bible through the Netanyahu family, the survival and flourishing of Jewish civilization has depended on what could be called a series of profiles in courage. Jews have followed the Torah of a God whom we have not been afraid to challenge. We overcome the most difficult circumstances, and continually prove our resilience against the jealous insecurities of others.

Jews can also be warriors. But when historically they lacked the means to fight on their own behalf, they developed alternate models of grit and strategies of self-defense by investing in brains over brawn. They even had the guts to mock some of those same strategies. Yiddish says: Got zol ophitn far goyishn koyakh un far yidishn moyakh; God protect us from the might of Gentiles and from the cleverness of Jews. We admit that even our best qualities don’t always serve their purpose.

As long as Jews remained confident that the Torah is a tree of life to those who cling to it, they fashioned models of courage appropriate to their situation. The key phrase here is as long as Jews remained confident. We know that in the 19th century, as ideas of Enlightenment began to take hold, many lost faith in the Jewish way of life. The forces that claimed to represent progress—in science and technology, arts and education, political and social thought—persuaded many Jews that other cultures were more advanced than their own.

This moral capitulation was hardly new; it had happened under Greece and Rome, under Christianity and Islam—but never before on so large a scale. The designated leaders of Diaspora Jewry, many of them dedicated students of Torah, had to decide whether to continue judging the surrounding world by their own standards or to start judging the Jews by “modern” or “progressive” standards. Given the attraction of liberal society and the assaults from anti-Jewish society, it took nerve and resolution to remain a dedicated Jew.

Terms like “courage” and “heroism” signify more than just being a mensch. Although being a decent human being is hard enough, “heroism” means overcoming adversity. So may we accurately apply it to Jews who just determine to remain Jews? The Talmud’s Ben Zoma seemed to be struggling with this issue when he put the rhetorical question, “Who is a hero?,” and answered: ha-kovesh et yitsro, that is, he who conquers—not the enemy, but his own passions, his desires, his instincts.

Do we agree with this? Does it really take heroism to remain a Jew?

Here is how I came to understand the question through the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, who struggled to create a new model of the modern Jewish hero. His contemporaries at the turn of the 20th century all understood that they had a problem in finding a Jewish hero among Jews who produced no soldiers, no statesmen or cardinals, and whose ideas of masculinity were so much at odds with European models. In his breakthrough story of 1887, Sholem Aleichem described himself as a boy who wanted a penknife more passionately than anything in his life. Of course, this goes totally against the values of the boy’s father. An angry and sickly man, the father ridicules the idea of playing with a toy—let alone a knife—instead of studying Torah. The father’s taboo is reinforced by the boy’s traditional schooling, which teaches that a boy must go against his desires.

One day when this boy sees his chance, he steals a penknife from one of the family’s lodgers. He hides it in the attic and plays with it whenever he can steal the time. But the panicked search for the object by the elders at home, along with other events at school, bring on such a crisis of conscience that although the boy is never suspected of the theft, he throws the penknife down the well and then collapses into a near-fatal illness—whereupon the father is frightened into showing his tenderness. When the son finally recovers, the father sends him to study with a kindlier teacher. The story ends with the boy happily vowing to himself: “I will never again steal, I will never again lie, I will always be honest, honest, honest. . . .” Sholem Aleichem published this story with the epigram, “lo tignov,” thou shalt not steal, from the Ten Commandments.

“The Penknife” was the first of many similarly intense stories by Sholem Aleichem about a boy who gives up his desires—in one story to play the fiddle, in another to join the actors in a Purim play. Renunciation is indeed a mighty theme in world literature; but why did Sholem Aleichem feel compelled to represent it as such a necessary choice?

Sholem Aleichem’s writing kept pace with his own development. In 1895, he created Tevye the Dairyman, the iconic image of a Jewish father, based on what was by then his own experience as the harried parent of several children and still counting. Tevye, whom the world knows as the hero of Fiddler on the Roof, is the tradition-bound father who now finds himself on the opposite side of the question of firmness versus leniency. The issue is not whether the child may indulge his desires but whether the parent must allow his children this indulgence. In Tevye’s case, his daughters are also now challenging him with their wants and needs—to follow their hearts into marriage, to follow the revolution, to convert to Christianity in order to marry a Ukrainian. Now that Sholem Aleichem is portraying the father rather than the child, he must recast the challenge: how far can he let Tevye give in to the desires of his children?

In successive chapters, written several years apart, Tevye bows to the wishes of his first two daughters, setting a pattern of accommodation to “modern children,” which is the title of one chapter. Our expectation that he will continue to show tolerance makes it all the more stunning when, breaking the pattern, he does not give in.

With the decision of Chava, his third daughter, to be converted by the local priest in order to marry Chvedka the Ukrainian comes the biggest temptation of Tevye’s life. She wants him to accept her anyway. He wavers out of love for her—oh how painfully he wavers, in a dramatic passage that leaves no one dry-eyed—even admitting that he cannot fully understand why there should be differences between Christians and Jews! Tevye wants with all his heart to give in, yet he becomes heroic—when he stifles his urge to be a liberal parent. He sits shiva for Chava and denies himself all contact with her.

Tevye’s final challenge comes in 1914, when Sholem Aleichem—who is always channeling current events—has him bow to the tsar’s expulsion of the Russian Jews from their villages. Dramatically, at the point of being driven out, Chava leaves her husband to return to her family. And this conclusion was historically justifiable because tsarist anti-Semitism did indeed prompt some Jews to return to their people. Although this ending is by no means a triumphant one, Chava’s return owes to, and has been predicated on, Tevye’s intransigence. The Jewish father has by this time taken quite a beating from life, but when he takes his final leave of us, he has won the right to reassure us: tell Jews everywhere not to worry: “the old God of Israel still lives!” Sholem Aleichem, our most optimistic writer, has taught us when securing the Jews means saying no.

But then what happens in America, where Tevye and his family are headed at the end of their saga? By 1906 the country was absorbing tens of thousands of Jews every year and most of them, just as with those crossing the southern border today, were single young men. Practiced in the arts of adaptation, Jews were the fastest among other immigrant groups to give up their Yiddish language, and, unlike in the case of the child with the penknife, there was no one to stop these boys from breaking away. As for the parents, they just wanted their children to advance. By the mid-20th century, we were in the Age of the American Jewish Son, and advance they did—in the professions, in business, and in the formation of culture.

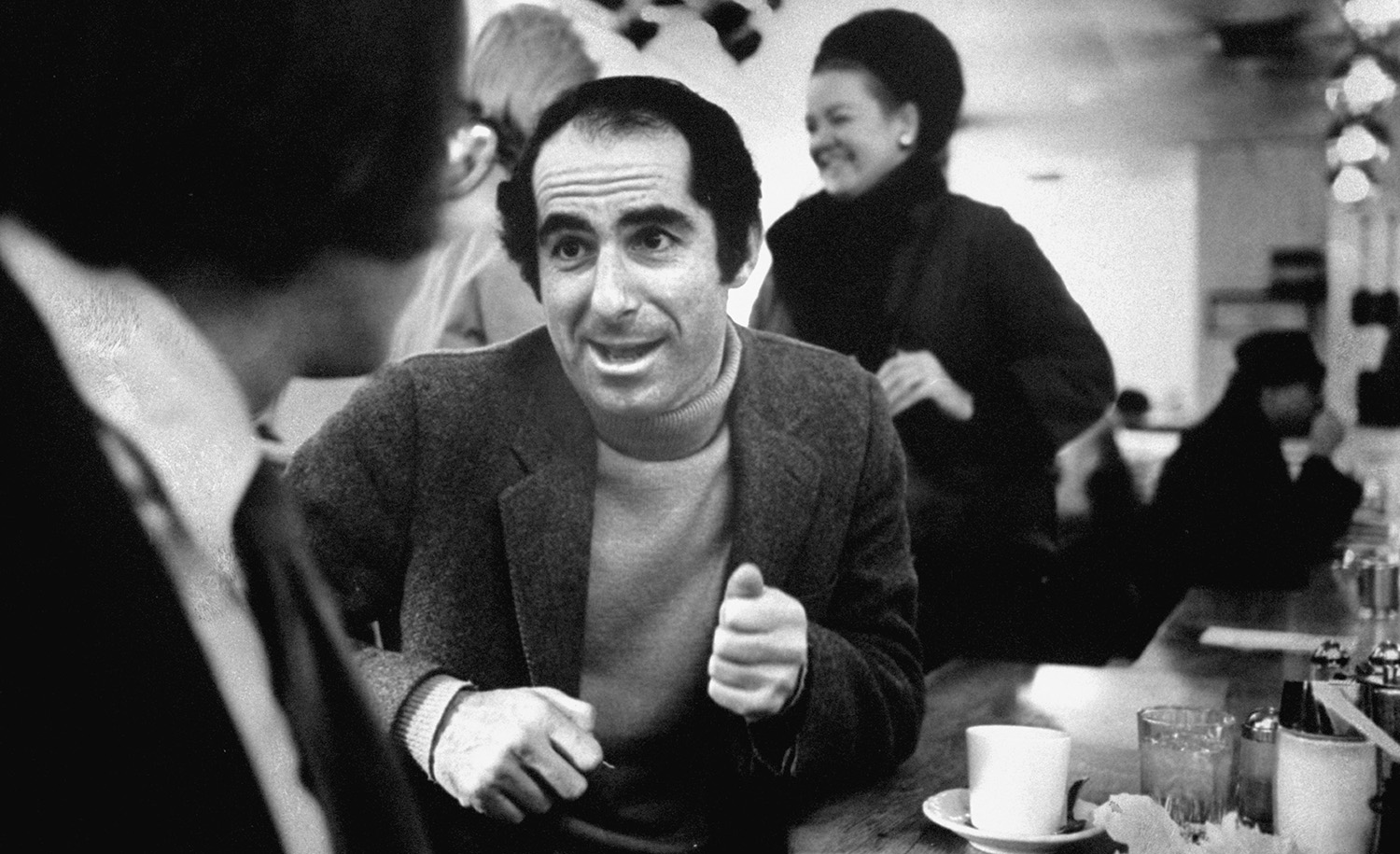

I grew up reading Commentary, in awe of the New York Intellectuals who by the 1960s seemed to be taking over American culture. One could almost feel their mothers chucking these boys under the chin, saying, “Who’s my clever little boy!” And one could also feel the absence of fathers making any Jewish demands. Delmore Schwartz, Lionel Trilling, Alfred Kazin, Saul Bellow, and a host of others wrote their versions of what, in his 1946 novel, Isaac Rosenfeld called Passage from Home—the Jewish son’s declaration of independence. Joking about the attempt of Jews to repress their desires reached its climax (if you’ll pardon the expression) in Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, where Jewish commandments are the butt of the comedy:

What else, I ask you, were all those prohibitive dietary rules and regulations all about to begin with, what else but to give us little Jewish children practice in being repressed? Practice, darling, practice, practice, practice, inhibition doesn’t grow on trees, you know—takes patience, . . . takes a dedicated and self-sacrificing parent and a hard-working attentive little child to create in only a few years’ time a really constrained and tight-ass human being.

This snippet from “Alex Portnoy’s Kosher Laws” shows how Sholem Aleichem’s theme of renunciation had coarsened in America. As one of the most talented writers of his generation, Philip Roth defined the American Jewish male as the never-to-become-a Jewish-father.

Please don’t mistake me for a cultural mashgiaḥ, a purveyor of Jewish political correctness. Quite the opposite—here, where Judaism is targeted by political correctness, I am affirming the right of Jews to maintain their Judaism. Far more devastating than Chava’s conversion at the end of Sholem Aleichem’s original story is the ending of Fiddler on the Roof, one of the finest musicals ever produced. As you may recall, the marvelous team of Joseph Stein and Sheldon Harnick—and they were marvelous—turn Chvedka, Chava’s Ukrainian suitor, into Tevye’s moral instructor. When the Jews of Anatevka are being driven out of their village, the couple say they are joining the exodus in solidarity. Tevye, however, fails to respond to their gesture, provoking Chvedka to say, “Some drive out with edicts, others with silence”—and thereby equating Tevye’s refusal to accept his daughter’s conversion with with the tsar’s evil expulsion of the Jews from Russia. By raising his hand to bless the couple, Tevye accepts the legitimacy of this same verdict.

Although the show won Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye greater exposure than he could otherwise have gained, it does so by robbing him of his daughter, just as Shakespeare does with Shylock. If you agree that self-differentiation is a cruel form of expulsion, you have condemned the familial basis of Judaism itself. We have to live with the fact that the masterpiece of American Jewish theater pronounces the liberal triumph over Judaism. It is no longer Christianity that claims the victory, as the priest does in Sholem Aleichem’s story; indeed, it is liberalism that rejects Christianity itself as part of the Judeo-Christian foundation of America.

The creators of Fiddler are Jewish sons who could not imagine themselves as Jewish fathers. Others are even more aggressive in wanting to take down that model. Joshua Cohen has just been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Netanyahus, which trivializes the most consequential family in recent Jewish history—the father a remarkable historian and sons who exemplify Jewish leadership against staggering odds. Cohen demonstrates his cleverness and literary talent, and justly defends his artistic right to reimagine these men any way he chooses. But that is precisely the point: this is how he uses his imagination—by clownishly describing the senior Netanyahu with his big toe poking through the hole in his sock; by portraying Yoni, leader of the raid on Entebbe, and Bibi, the longest-serving Israeli prime minister, as uncivilized bratty kids. What fun to portray an Israeli family of Churchillian stature from a debased American perspective! Whatever Cohen thought he was doing through his reductionism, he shows what a liability we have become to the Jewish state, cheapening ourselves to please the worst in America rather than affirming the greatness our people has shown.

Against the puerile instinct to tear down, let us build. The Jewish father is the hero to whom American Jews must now pay due honor. Among Jews, everything begins with the family, and, like it or not (I happen to like it), authority comes in a male image of Avinu sheba-shamayim, our Father in heaven. If we are made in the divine image, we may choose which of its many aspects we want for ourselves, but we must continue to honor the paternal image as anchor of our families and our people.

When Jews live as a minority among others, as we do here in America, we are unavoidably influenced by the conditions that govern all its citizens. Very little in today’s America contributes to strengthening fatherhood and, as I’ve said, much works against it—including, most recently, the misandry of the feminist movement, the grievance war on white men, and the assault on Jews in particular. It is not easy for young Jewish men in uncertain times to enter voluntarily into marriage with strong-willed Jewish women (are there any other kind)? And I stopped counting the Gentile women I know who have told me how much they love their Jewish sons-in-law—so why not go where you are appreciated?

The Jewish father is expected to provide for his family and to supervise the education of his children. The more responsibly he does this, the more he will be called upon to assume responsibility in other areas of life as well, including the community, the civic society, and the nation. Yet he who used to be compensated for his effort with a seat at the head of the table is now asked to apologize for his “privilege.”

I hope you realize that I single out the heroism of the American Jewish father not in order to detract from other forms of courage, and other models of excellence, but because it has never been under greater assault. We need Jewish men to stand up to the wolf pack that is tearing them down, and to set the example for others in our society who need that example no less.

It is time the ideal of the American Jewish father replaces that of the beloved Jewish son: fathers who transmit the best in our heritage, who stand up for us against the worst around us, who extend their love of family to the nation and who build organizations like the one that brings us together here. Who is the American Jewish hero? He is all around us—he needs only to be acclaimed.

This essay has been adapted from a speech given on June 12 at the Jewish Leadership Conference in New York.

More about: Arts & Culture