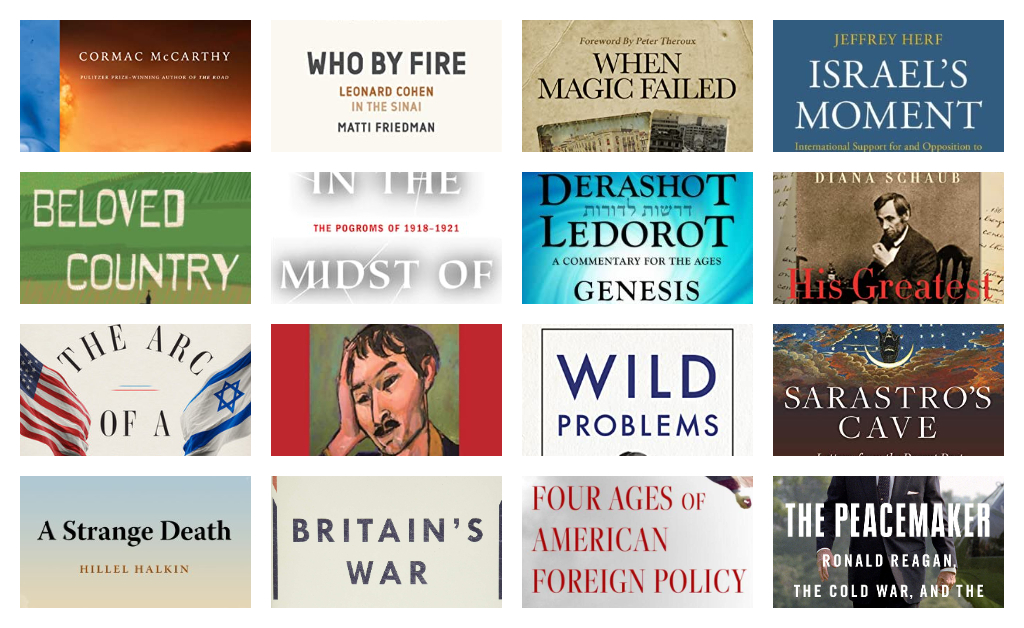

To mark the close of 2022, we asked several of our writers to name the best books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. Their answers appear below. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2022. Classic books are listed by their original publication dates.)

Elliott Abrams

For history buffs and Anglophiles, Daniel Todman’s two-volume Britain’s War (Oxford, 2016 and 2020, 1,824pp., $74.90) deserves the prizes it has won. No other book about Britain in the Second World War contains as complete (or as fascinating) a description of how the war was experienced by those living in the UK during those terrible years. Will Inboden’s new book about Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy, The Peacemaker: Ronald Reagan, the Cold War, and the World on the Brink (Dutton 608pp., $35), exemplifies judicious and balanced historical writing. Organized chronologically rather than thematically, it describes as no other previous work has how Reagan’s foreign policy came together and how the great successes (and some failures) of his administration came to pass.

Not having any favorite current novelists, I’ve been rereading the fiction of Anthony Trollope. Last year, I recommended his Palliser novels. This year I’ve been reading his six-volume Chronicles of Barsetshire series (Oxford, 1855-1867, $91.70). Trollope’s fiction never disappoints. If you’ve never read it, correct the error. The characters, social commentary, plotting, and wit are endlessly rewarding.

Tamara Berens

Matthew Continetti’s The Right: The Hundred Year War for American Conservatism (Basic, 496pp., $32) is a masterful history of the conservative movement and Republican politics—spanning the highs and lows of one century, documenting successful and failed attempts to sway conservatism one way or another, and uncovering the smallest (and most important) of details. In his review in Mosaic, Rabbi Meir Soloveichik mentions the dramatic image of Ronald Reagan’s silhouette that adorns the cover. It is striking that Reagan cuts such a recognizable figure even from the back. Which other president would we recognize from only a suit, a lock of hair, and an ear?

I approached The Right hoping to understand better what went wrong with conservatism after Reagan, the man who first endeared me to America itself. Continetti explains that the War on Terror of the 2000s could never be the unifying force that was the cold war in Reagan’s day, which brought together the religious right, ex-Communists, neoconservatives, and classical liberals. However, his book also suggests that Reagan himself should be viewed as an aberration for the right, and perhaps even the conservative movement. His sunny disposition and popular appeal held together the disparate factions, which have since splintered almost completely.

Continetti leaves no event, magazine, or person who influenced American conservatism untouched. His treatment of the movement reminds me of a line in a T.S. Eliot poem: “Like a patient etherized upon a table.” While Continetti has his own opinions on what directions he would like American conservativism to take, he spares no faction within the movement his criticism, even those he views favorably. The Right left me with a much greater appreciation for the magnitude of the right’s achievements—good and bad.

I’ve long admired the work of Gertrude Himmelfarb; The De-Moralization of Society and One Nation, Two Cultures are among my favorites. Yet I must admit that I’ve avoided Himmelfarb’s much-praised work on Britain—the country where I was born, raised, and educated—and especially on British philo-Semitism, because I was afraid of agreeing with it. It had been my view that America is the great philo-Semitic nation, and that, unlike other elements of American culture and the American political tradition, English Protestantism has little to do with that.

But this year I finally read The People of the Book: Philosemitism in England, from Cromwell to Churchill (Encounter, 2011, 183pp. $23.95), in which Himmelfarb provides a history of philo-Semitism, Zionism, and the emancipation or political toleration of the Jews in Britain. From her treatment of figures from the more obscure Henry Finch and Robert Grant to the more familiar Oliver Cromwell, Winston Churchill, and George Eliot, I came to see that I was wrong about British philo-Semitism. As Himmelfarb states at the book’s close, this history should recall England to its past glory—but it “may also recall Jews to a glory they themselves tend to forget.”

Reading Himmelfarb makes it even harder for me to contend with modern Britain, which is so devoid of the meaningful philo-Semitism and Zionism that Himmelfarb beautifully explores. While toleration thankfully remains, it has lost its former animating spirit. Even pro-Israel politicians tiptoe around British-Jewish support for Israel, assuring the British public that British Jews have nothing in common with IDF soldiers.

Himmelfarb’s essay on the novelist George Eliot’s life and her key Zionist text, Daniel Deronda, should be indispensable for all Jewish readers (and students of literature, though the text’s Zionist themes were too often disparaged by literary critics). Himmelfarb has a stand-alone book available for purchase, The Jewish Odyssey of George Eliot, which is marvelous too. As Himmelfarb points out, Eliot understood Jewish nationality and spirituality better than most Jews. Himmelfarb writes, quoting from Eliot: “Nationality, then, is of the essence of Judaism. The question is whether there are enough worthy Jews, ‘some new Ezras, some modern Maccabees,’ who by their heroic example would set about making their people ‘once more one among the nations.’”

Andrew Koss

While World War I officially ended at 11:00 am on November 11, 1918, the war continued in much of Eastern Europe until 1922, in the form of several overlapping, confusing, and bloody conflicts that are little known in the West. During these wars, soldiers on various sides—sometimes joined by local civilians—slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Jews, first in pogroms and then in what might better be called mass executions. Jeffrey Veidlinger skillfully puts together the wealth of available information about these episodes in his highly readable, richly detailed, and horrifying In the Midst of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms of 1918–1921 and the Onset of the Holocaust (Metropolitan, 2021, 480pp., $35). Scholars will no doubt continue to dispute Veidlinger’s various interpretative moves, but such debates are only secondary to the great service he has done in telling a story every Jew, and everyone who cares about the fate of the Jews and of Europe, should be aware of. I recommend reading the book alongside Henry Abramson’s truly excellent A Prayer for the Government.

In an entirely different vein, I’d like to recommend my friend Lazarre Seymour Simckes’s two-volume My Collected Plays (398pp., $35.64). These plays are simultaneously bizarre, challenging, wildly creative, entertaining, and sometimes downright frustrating. Several take up explicitly Jewish themes—I’m especially partial to “Ten Best Martyrs of the Year”—and all are a product of what one might call a Jewish sensibility, informed by a professional knowledge of psychology and extensive reading of midrash.

I first became aware of the work of the South African novelist Alan Paton when listening to a lecture by Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter, which is alone evidence that he is worth reading. This year, I read Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (Scribner, 1945, 316pp., $17), a breathtakingly beautiful and moving work about people caught up in South Africa’s tragedy, exposing the many evils of apartheid in a way that is never didactic or propagandistic but always humane. There is a powerful Old Testament feel to the book’s style, perhaps befitting a work whose hero is a priest. As it is the story of a righteous man’s suffering, it would be easy to compare it to Job, but more than anything it put me in mind of the book of Ruth.

For those who read Hebrew, I’d also like to recommend another classic I finished this year, Rabbi Shimon Schwab’s collected writings on the Pentateuch, Ma’yan Beit ha-Sho’evah (Mesorah, 1994, 483pp, $29.99). Schwab (1908-1995) was the scion—in a metaphorical rather than genetic sense—of a chain of rabbis going back to Samson Raphael Hirsch, one of the founders of Modern Orthodoxy in 19th-century Germany. Himself born in Hirsch’s city, Frankfurt-am-Main, Schwab was also educated in East European yeshivas, and combines these two traditions. While I must admit that I find Schwab’s opinions about Zionism terribly misguided, anyone willing to look past that will see a unique and truly original religious thinker.

Daniel Polisar

This year, I read a number of new books that will remain with me well into the future. In narrowing the field down to my top picks, I ended up with four, all non-fiction.

Michael Mandelbaum’s The Four Ages of American Foreign Policy: Weak Power, Great Power, Superpower, Hyperpower (Oxford, 624pp., $34.95), a magisterial work that covers the two-and-a-half centuries from 1765 to 2015, is likely to be the definitive treatment of its subject for many decades to come. Writing in a clear, engaging, and deceptively simple style, Mandelbaum deftly weaves together insights drawn from diplomatic history, military affairs, economics, politics, the biographies of greater and lesser leaders, literature, and culture. For virtually every period and key episode he touches, he provides a readable and often gripping account of the major developments embedded within a powerful theoretical framework and chock full of new understandings of seemingly familiar events. Readers of this work will emerge with a perspective that will guide not only the way they see America’s past, but also its current policies and the prospects for its future and that of the world it will continue to shape.

Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us (Portfolio, 224pp., $27) is a slim volume by Russ Roberts, a friend and colleague blessed with the remarkable ability to offer thought-provoking treatments that draw on his training as an economist and the breathtakingly wide range of his erudition, honed as host of the EconTalk podcast for over a decade and a half. Like his earlier How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life, Roberts’s most recent book draws on the ideas of great thinkers, the findings of more contemporary scholars, and his own judgment and moral compass, which he combines in order to help readers face the daunting challenge of becoming better, more fulfilled human beings. Wild Problems exposes the limits of conventional approaches to making choices based on the accumulation of data and the weighing and pros and cons, and argues persuasively that in addressing the big issues all of us must confront, we need to rely on bedrock principles, tradition, and intuition, and to be guided by a belief in our own fundamental decency, our ability to become what we aspire to be, and the possibilities of our own flourishing. This book is at once deeply inspiring and eminently practical.

Matti Friedman’s Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai (Spiegel & Grau, 224pp., $27) passed the most stringent test for readability of any book I can recall in the last two decades. I was on an overnight flight from Los Angeles to Israel, had been working and reading non-stop for several hours, and despite my exhaustion decided I would stay awake through the landing rather than falling into the fitful sleep with which such plane rides provide me. I started a number of books, none of which captured my attention or staved off my growing weariness, until I turned to the latest offering by Friedman—whose writing and speaking I have always found to be compelling.

I read Who By Fire cover to cover and came away with a far better appreciation for the terror experienced by Israel’s soldiers during the Yom Kippur War in October 1973, their human decency and vulnerability, and the breathtaking, understated heroism they showed. I also grew in my appreciation for Leonard Cohen, who for good reason earned iconic status in the Jewish state despite and in some ways because of his complicated relationship with his faith and his people. Friedman’s book, like the subjects it describes, is beautiful, haunting, and profoundly memorable.

My final choice is in some ways a new book and in others a classic, Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings (Library of the Jewish People, $134.95) edited by Gil Troy, is a three-volume work whose nearly 3,000 pages cover the rise of the Zionist idea (1894-1896), the creation of the Zionist movement (1897-1900), and Herzl’s transformation into a Zionist statesman (1901-1904). As I’ve lectured and taught about Herzl for many years, I had previously read much of the material in these volumes, but nonetheless found this collection to be a superb vehicle for thinking anew about the once-in-a-millennium leader without whom there would almost certainly be no Jewish state today. The power of this set resides not only in its highly readable and beautifully laid-out translations, but especially in the bold decision to organize Herzl’s works chronologically so that the reader can see the development of the man and the movement, with all the drama and complexity this entailed.

Another crucial element that contributes to the reader’s understanding are the dozen introductions Troy authored as part of this undertaking, beginning with a lengthy essay on “Theodor Herzl and the Jews’ Leap of Hope” and continuing with pieces introducing the challenges, developments, and major writings for each of the eleven years of Herzl’s whirlwind of Zionist activity, from 1894 until his untimely death at age forty-four. This collection has the potential to bring back to center stage, for English readers, a towering figure who remains a powerful model for Jewish leaders and for nationalists today.

Neil Rogachevsky

I am exercising my privilege as Mosaic columnist to recommend once again Fouad Ajami’s posthumously published When Magic Failed: A Memoir of a Lebanese Childhood, Caught Between East and West (Bombardier, 256pp., $28). Much more than a simple memoir, the book is an extraordinary meditation on political modernity, tradition, political failure in the Middle East, and the promise of America.

Amid a plethora of new books on the America-Israel relationship, Jeffrey Herf’s Israel’s Moment: International Support for and Opposition to Establishing the Jewish State, 1945-1949 (Cambridge, 450pp., $39.99) stands out. Looking at the archival evidence, Herf shows that opposition to Zionism was much more deeply ingrained in the upper echelons of American government after World War II than has typically been understood. U.S. support for the establishment of Israel was in large measure due to Harry Truman’s courage and judgment. Herf’s excellent history reminds us that strong U.S.-Israel relations were not inevitable.

In His Greatest Speeches: How Lincoln Moved the Nation (St. Martin’s, 2021, 224pp., $27.99), Diana Schaub presents a line-by-line reading of the Lyceum address, the Gettysburg address, and the second inaugural. These speeches belong not only to America but to the ages, and Schaub draws out the extraordinary subtlety of Abraham Lincoln’s views on political and theological matters.

Finally, I’d like to mention Richard Velkley’s allegorical tragicomic novel Sarastro’s Cave: Letters from the Recent Past (2021, Mercer University, 100pp., $20), which depicts the promises and perils of the “philosophic life” in our post-enlightenment age.

Sarah Rindner

Until recently, I was unaware that Cormac McCarthy—perhaps one of America’s greatest living novelists—had much to say about Jews or Judaism. But his new novel, The Passenger (Knopf, 400pp., $30), published sixteen years after his previous book, concerns two Jewish siblings whose last name is Western. Despite the nominal Jewishness of the main characters, one a deep-sea salvage diver, the other a mathematical savant, McCarthy’s intriguing and challenging new novel is a reflection of the crisis and decay of Western, largely Christian, civilization. Bobby and Alicia Western are intimately connected to the central moments of civilizational collapse: members of their family were killed in the Holocaust, and their scientist father worked on the development of the nuclear bomb. The siblings also stand apart as outsiders and observers.

McCarthy’s prose is beautiful and measured, employing his characteristic biblical terseness to pack maximum effect into the fewest possible words. In the Passenger, and in its newly published companion novel Stella Maris, McCarthy seeks to diagnose social and spiritual maladies and even probe the possibility of a cure. It’s interesting that he attempts to do this while repeatedly emphasizing the Jewishness of his sympathetic main characters, even if his engagement with the actual substance of Judaism does not stretch far beyond that. As one character observes to the sister Alicia, “an outlier such as yourself always raises again the question as to where this ship is headed and why.”

Ruth Wisse’s new translated and edited version of Chaim Grade’s My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner (Toby, 144pp., $19.95), which originally appeared in Mosaic, has now been published as a standalone book that includes the original Yiddish. The edition is a gift to students of Jewish literature, and to anyone interested in engaging in the eternal Jewish debate which is adjudicated within. The story tracks an ongoing dialogue between two East European yeshiva graduates as they meet before, during, and after World War II. Hersh Rasseyner is a passionate and principled adherent of the Musar movement, which, as the translation explains, “gives special importance to ethical and ascetic elements in Judaism.” His interlocutor, Chaim Vilner, has left his yeshiva past for a more urbane, cosmopolitan life as a secular Yiddish writer. Both suffer greatly in the Shoah, yet their experiences only reinforce, rather than undermine, the firmness of their convictions.

Wisse’s updated version is based on Milton Himmelfarb’s iconic translation for Commentary but also contains key changes, particularly in Wisse’s preservation of certain traditional biblical and rabbinic phraseology, giving the language of the story a uniquely Jewish texture that was downplayed in the earlier translation. Wisse also includes the normally excised interlude with Rasseyner’s fervent student Yehoshua, which connects the world of The Quarrel to the Orthodox world of today.

A pleasant recent day trip to the northern Israeli town Zikhron Yaakov inspired me to pick up a remarkable book by Hillel Halkin called A Strange Death (Public Affairs, 388pp., $26). Published in 2005, it depicts the complicated and fascinating recent history that lies beneath this seemingly sleepy pastoral town. Zikhron Yaakov was famously home to the erudite and talented Aaronsohn family, who also joined the Nili spy ring during World War I. Believing Britain would be more sympathetic to the establishment of a Jewish homeland, Nili sought to undermine Ottoman sovereignty in what was then Palestine. The beautiful and courageous Sarah Aaronsohn was famously betrayed to the Ottoman authorities, resulting in her interrogation, torture, and subsequent suicide.

Halkin brilliantly explores the lingering mystery of Sarah’s betrayal, possibly at the hands of one of her Jewish neighbors. To do so, he uncovers simmering resentments within Zikhron Yaakov, class tensions among Jewish immigrants of various backgrounds, relationships with surrounding Arab farmers and Bedouin tribes, and local romantic and economic drama. He performs this investigation as a historian, as a close reader of literature and texts, and as a curious neighbor who happened to move to Zikhron Yaakov in the 1970s unaware of this complex history. As a recent American transplant to an Israeli community not too far from this one, I can relate to being a newcomer in a place where past and present seem to coexist simultaneously and where one’s casual observation of tension among neighbors may lead to an encounter with the past stranger than anything one would have ever expected.

Jonathan Silver

The need to worship is an inextricable aspect of the human condition. That is why what sometimes looks like secularization is instead the adoption of alternative objects of devotion. In his 2022 book Bad Religion, Ross Douthat described how America doesn’t have too much or too little religion, but argued instead that modern political and cultural heresies have coopted traditional forms and institutions.

American Jewry is not immune to this kind of cultural transposition, and no congregation on the denominational spectrum is unaffected by this. Traditional religious communities now face a choice. They can help restore our social order, or they can be force-multipliers of our social unraveling. If the country is going to benefit from its religious congregations, those congregations are going to have to embrace a more confident, countercultural ethos. Religious leaders will need to remember that their highest obligations are higher than America’s culture wars. And so my first recommendation this year is a set of weekly parashah commentaries that are self-consciously presented as an alternative and counterweight to the modes and orders of contemporary society. Norman Lamm’s Derashot Ledorot (Maggid, 1,120pp., $124) are published in five volumes, each corresponding to one book of the Hebrew Bible.

My second recommendation is also related to the American character. Scholars, political figures, and media personalities, no less than social-media conspiracists seem to believe that the enduring strength of the U.S.-Israel relationship is a function of American Jewry. And of course, this is also a cherished fable that American Jews hold of themselves. Walter Russell Mead’s The Arc of a Covenant The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People (Knopf, 672pp., $35) is the latest, and perhaps the most comprehensive, attempt to explain why that isn’t so. America’s sympathy for the idea of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel is a fascinating mirror in whose reflection readers can learn about how America understands itself.

There are many religious and cultural affinities between American Christianity and the Israel of its imagining, and these connections are deeply rooted in American history. Mead tells that cultural story well, but his best chapters unspool the American discovery of Israel’s political utility during the cold war. If you liked Michael Oren’s 2008 Power, Faith, and Fantasy, or Samuel Goldman’s 2018 God’s Country, you’ll find much to admire in The Arc of a Covenant.

My third recommendation honors a writer and friend of Mosaic that we lost this year. Newsrooms, universities, and businesses large and small are all beset by a rising generation, implacably devoted to progressive and radical causes, setting their sights on the ideological impurities of their elders. The pattern of the young visiting revenge on the old is not new; it, and its social ramifications, comprise the theme of Book VIII of Plato’s Republic. But no one in post-war America observed this timeless generational dynamic more accutely than Midge Decter, the author, editor, and essayist who passed away in May.

In Liberal Parents, Radical Children (Coward McCann, 1975, 248pp.), she portrays how the parents of the dropouts, druggies, sexual revolutionaries, and radicals of her day were themselves complicit in engendering the habits of mind and heart that most bothered them in their children. The sins of the fathers visited upon the sons, indeed. Though the book is addressed to the rising generation, it can be read with even more profit by all those who have a hand in shaping the tastes and passions of the young.