Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

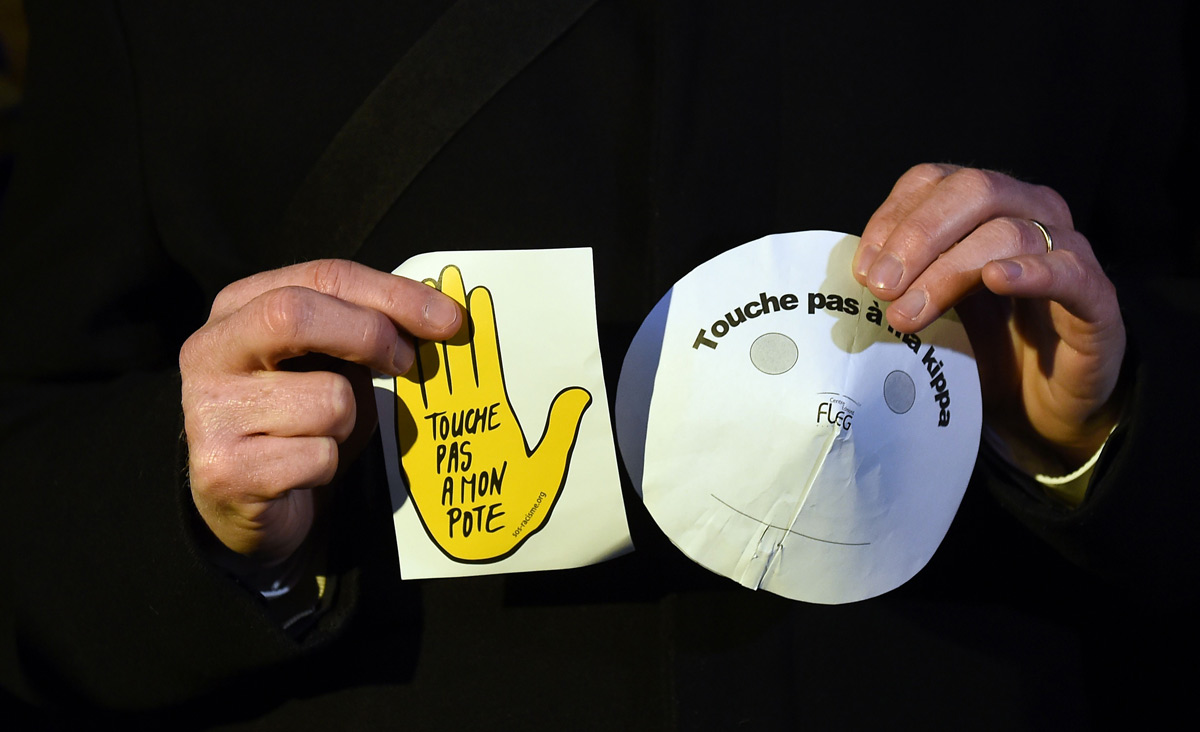

“A campaign was launched in France calling on all citizens to don the Jewish skullcap on Friday [January 16],” reported that day’s Algemeiner, “after the Marseille chief rabbi urged fellow residents to avoid wearing kippot, out of fear of anti-Semitic terror. . . . The campaign called on citizens to put on the yarmulke at 10 a.m. on Friday in a coordinated effort.”

Skullcap, kippah (or kipah), yarmulke: three different words, all in one short paragraph, for the same round Jewish head covering. Are they interchangeable?

Not quite. To begin with, kippah alone is italicized, since it does not appear as a recognized word in English dictionaries. More importantly, although all kippot and yarmulkes are skullcaps, and every yarmulke is a kippah, not every kippah is a yarmulke. This is because the Hebrew word kippah, as it is used in Israel and increasingly in the Diaspora, denotes any skullcap worn by a Jew for religious reasons, whereas “yarmulke,” which comes from Yiddish, generally refers only to the sewn satin or felt cap, commonly with a cotton lining, of Ashkenazi Eastern Europe. Although it needn’t necessarily be black any more, as all yarmulkes once were and most still are, it cannot be knit, crocheted, or embroidered like many kippot. If it were, it, too, in the contemporary language of most American Jews, would be no longer a yarmulke but a kippah.

The two words are not equally old. In early rabbinic Hebrew, kippah means a vault or dome, whether of a building or of the heavens; deriving from the biblical verb kafaf, to bend or force down from above, it also came to signify a man or woman’s domelike cap—unless kippah in the latter sense derives independently from cappa, a Latin word for a head covering that has given us our English “cap.” But prior to the 6th or 7th century there is no written attestation for cappa, which probably comes from caput, “head,” and it is even possible, if not terribly likely, that it was cappa that descended from kippah.

The medieval etymology of yarmulke was for a long time even less clear. The word was traced to Polish, in which it can be found as far back as the early 1600s, though its presence in Slavic languages is almost certainly a borrowing from Yiddish rather than vice-versa; to Turkish yarmuluk, “rain covering,” which—quite apart from the improbability of a rain hood turning into a skullcap—would make it just about the only Turkish word ever to have entered Yiddish; to German Jahrmarkt, “country [literally, “annual”] fair,” because Jews supposedly wore it on such occasions, and to the even more farfetched Hebrew-Aramaic hybrid y’rey malka, “a fearer of the king,” the “fearer” supposedly being the skullcapped Jew and “the king,” God.

In the end, the mystery may have been solved by the scholar and Reform rabbi W. Gunther Plaut, who argued persuasively in a 1955 article that the real source of yarmulke was medieval Latin. Plaut began by observing that the amice or almuce (with its “c” pronounced as “k”), a cape-like church vestment covering the head and shoulders, was similar to head coverings worn by Jews in the Middle Ages; proceeded to point out that its diminutive of almucella or armucella, which gave German and Scots English respectively the words Műtze and “mutch,” a cap, referred to the top part of the almuce alone; and concluded that the word also entered Yiddish as yarmulke. This is a far more reasonable theory than any of the others.

Was the yarmulke a medieval innovation? Or was it, rather, the old talmudic-period kippah under a different name? There being no visual evidence of how Jews dressed in either the street or the synagogue prior to the Middle Ages, both possibilities can be defended. In favor of the first is the fact that the word kippah in the sense of a skullcap rarely appears in medieval Hebrew, and that the first explicit mention of the yarmulke as a characteristically Jewish form of dress dates to the 17th century. Medieval Jewish head coverings are referred to in Jewish literature by other words, and the earliest illustrations of medieval Jews show them wearing an assortment of hats and cowls of which the skullcap is not one.

But there are also two counter-arguments. One is that a religious significance that might have institutionalized the kippah in Jewish life is already imputed to it in the Talmud, where the opinion is cited that one of the items of the High Priest’s garments, placed at the center of his mitznefet or turban, was a “woolen kippah.”

The second counter-argument is the historically widespread wearing of a wool or cotton skullcap throughout the Muslim world as a sign of religious piety. The devotional character of this skullcap, called a taqiyah in most Arabic-speaking countries, is ascribed by Islamic tradition to Muhammad’s having gone about in one. Whether he did or not, the custom must have been adopted from somewhere—and as is the case with many features of early Islam, Judaism is a likely source (as it also may be of the skullcap worn by Catholic prelates). If Middle Eastern Jews in Muhammad’s time—that is, at the start of the Middle Ages—were wearing a kippah for religious reasons, this was in all likelihood a custom that descended from ancient Palestine and has continued to our own times.

Today, of course, there is an entire semiotics of Jewish skullcappery, ranging from the traditional black Ashkenazi yarmulke, now worn by ultra- or semi-ultra-Orthodox non-Ashkenazim as well, to the small, often multi-colored, knit kippah that began as a badge of modern Orthodoxy in Israel and spread from there to the United States and elsewhere. In between these two are the increasingly popular medium- and large-sized knit kippah, sometimes indicative of a stricter level of religious observance, though also favored by women who have begun to wear kippot to religious services; the intricately embroidered Bukharian-style kippah, often with raised, partially squared sides, that may declare its wearer’s adherence to some more flamboyant or anti-establishment form of Judaism; the white knit kippah, with or without a pompom, that is worn by Bratslaver Ḥasidim, etc. Look what’s on my head, such symbolism states, and you’ll know the type of Jew I am.

More inclusive than “yarmulke” and more Jewish-sounding than “skullcap,” kippah is a word that has taken root among American Jews and is well on its way to losing the italics it is still printed in. Just make sure to say “ki-PAH,” with the stress on the second syllable, which is the Israeli pronunciation. In Israel, too, to be sure the East-European-sounding “KI-pah” is sometimes heard, but this has a derogatory tone and is a secular Israeli way of mocking the kippah by implicitly equating it with the exilic yarmulke. It is to be avoided.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Hebrew, History & Ideas, Philologos, Yiddish