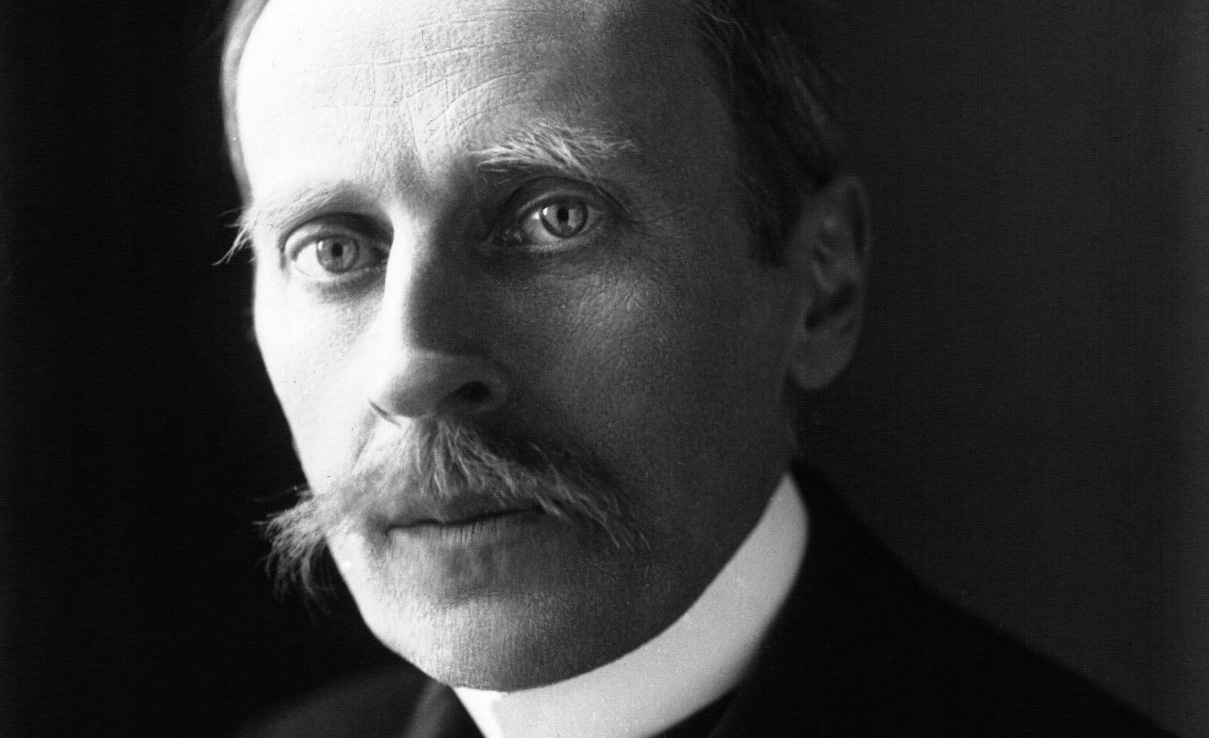

For many Europeans of my generation—those who came of age before World War II—Romain Rolland (1866-1944) was not only the most important writer of our time but a beacon of light in a very dark world. Novelist, essayist, dramatist, art historian, humanist, pacifist, idealist without compare, he was our great guide in the battle against philistine obscurantism on the one hand, creeping barbarity on the other.

Were we right about him? Since his name is now all but unknown, it would be helpful to start with the bare facts.

Born in a small town in Burgundy, France, Rolland was early on recognized as a budding young intellectual star. After attending the elite Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, he became a teacher and lecturer in the history of art and music. In those days, he seems not to have had much interest in politics; throughout the furor over the Dreyfus affair, the great political battleground of his thirties, he appeared to favor neither side.

The same irenic (or perhaps non-committal) temperament informs Jean-Christophe, the huge ten-volume novel that made him famous. Appearing in installments from 1904 to 1912, it tells the cradle-to-grave story of a young German composer who makes his way to Paris, what he experienced there—especially his burgeoning friendship with a young Frenchman—and how these experiences influenced him and shaped his life and ideas. For that novel, and for his writings at the outbreak of World War I urging Germany and France to resolve their differences through a shared devotion to the lofty goals of truth and humanity, he was awarded the 1915 Nobel Prize in Literature. Fittingly, he passed along the prize money to the Red Cross in Geneva. Later on he wrote a series of what would become known as “heroic biographies”; among the passionately admired figures profiled in these books were Beethoven, Michelangelo, Tolstoy, and Gandhi.

It was Rolland’s stand in the Great War, and specifically his stirring denunciations of the senseless mass murder that sustained it, that made him so influential at the time, and even more so in later years when that conflict came to be seen as the root from which sprang the subsequent scourges of fascism, Communism, and World War II. In the 1930s, he became the leading intellectual supporter of the anti-fascist cause in Europe.

And here things began to become more complicated. An incurable romantic, Rolland was a fervent admirer of German culture, and the most eminent interpreter of Germany in France. After 1933, although saddened by the rise of Hitler in Germany, he still regarded Italian fascism and Mussolini as a greater danger than Nazism. (The fact that his earlier books were still being published in Germany may have affected that judgment.) At the same time, however, he also came to adore Josef Stalin, going so far as to justify almost all of the Soviet tyrant’s crimes. No Marxist, not even a socialist, he defended the Soviet Union as a leading force in the battle against fascism, and that conviction, together with his impulsive political romanticism, enabled him to suppress any misgivings he might have had about the Moscow show trials of 1936-1938 and the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939.

Rolland also justified his personal relationship with Stalin—he’d enjoyed audiences with the dictator in the mid-1930s—on the grounds that it enabled him to intervene occasionally and do some good, for instance by achieving the release from prison of the writer Victor Serge and perhaps others. In those years, the Russians needed a figure of Rolland’s standing, since some Western intellectuals were beginning to turn against the sweeping Soviet experiment in human engineering; the defection of André Gide, the famous French writer and once-ardent fellow traveler, was especially damaging. Still, there were narrow limits to the party’s readiness to make concessions, and as time went on Rolland’s requests were progressively ignored.

Rolland had spent the interwar years in Switzerland, but in 1938, accompanied by his second wife, a Russian princess by origin, he decided to move back to the French province where he was born. There he spent the war years under German occupation. Until recently, little was known about his views and impressions of that time, but this changed with the 2012 release in France of Journal de Vézelay 1938-1944, his wartime diary—a publication event wisely postponed by his widow and heirs for 70-odd years.

Rolland was in no way persecuted by France’s Nazi occupiers. On the contrary, he was frequently visited by, among others, German army officers who knew and esteemed his books. (He seems to have requested that they refrain from showing up in full uniform.) At a time when food was scarce, he appears to have received special rations. At one point he even wrote that if his poor country had to be occupied, he would much prefer the occupiers be German rather than American—a bizarre statement not least because anti-Americanism was not yet de rigueur in France, and Rolland himself knew little if anything about America.

One can think of mitigating circumstances to extenuate, if not to excuse, Rolland’s failure to understand either the United States or, more consequentially, the Soviet Union. About the latter, it suffices to note that his knowledge was gleaned from his study of Tolstoy—and then from his second wife, Maria Kudasheva, a member of the “white” (that is, anti-Bolshevik) émigré community who had made her peace with the new regime. But in the case of Germany, its language, its history, and its culture, he had no such alibi. Although by no means enamored of Hitler—on at least one occasion before the outbreak of war, he wrote in his diary that the dictator should be destroyed—he was nevertheless baffled by the Nazi phenomenon and totally misunderstood it. In one of the least accurate and most blandly inadequate attempts ever devised to grasp its essence, he defined Nazism as “socialist Caesarism.”

What, then, of Rolland and the Jews? Individual Jews always played an important role both in his life and in his work, but only now, thanks to the wartime diary, has a full, and very contradictory, picture emerged. Among his close Jewish friends were the writer André Suares, a contemporary of his at the Ecole Normale, and Stefan Zweig, whose biography of Rolland helped make him famous in Germany.

Then, too, Rolland’s first wife, Colette Bréal, a fellow art historian, was of Jewish origin. But the marriage did not work out, at least in part because she found the husband of one of her cousins to be more amusing company. That brilliant young intellectual was none other than Léon Blum, the future leader of the French Socialist party and a prime minister of France before World War II and, following his liberation from internment in Dachau, for a brief time afterward. Rolland calls Blum “my intimate enemy.”

Jews also appear prominently in Rolland’s novel Jean-Christophe. There he clearly signals his approval of the older generation of Jews in Germany and France, whom he presents as God-fearing, industrious, and reliable. By the same token, he very much disapproves of the following generation, typified, in his account, by irreligious modernists, rootless and devoid of values. (But neither does he spare the Zionists, who were certainly searching for their roots.) Where the life of culture is concerned in particular, the young Jewish intellectuals in Jean-Christophe represent an element of decay and corruption—and above all are said to be far too numerous on the artistic scene, especially in the theater.

It is of some significance that this kind of criticism was very much in the air at the time, not only in France but also in Germany. In 1912, the same year the final volume in Rolland’s masterpiece was published, a major debate raged in Kunstwart, a leading German periodical, over the alleged predominance of Jews in the world of culture and the arts. Still, it’s important to note that Rolland would stop quite a bit short of Nazi-style anti-Semitism. Much as he disliked most Jews and thought them too influential, he rejected the offer of a friend to collaborate in an explicitly pro-Nazi journal and strongly denounced its orientation.

Looking back at the role of Romain Rolland 70 years after his death, one is bound to feel considerable unease at his deeply disturbing attitude toward Stalinism and his utter failure to grapple with the meaning of Nazism, the other great iniquity of his time. How to explain this? He had grown up in the settled world of the 19th century, so different from the tumultuous world of the 1930s. In the latter’s political circumstances, while remaining a person of good will, he simply could not and would not confront those disposed toward unadulterated evil: a case, in the end, of massive naïveté compounded by selective and fatal self-delusion. The fact that his works were widely adored not only in France but even more so elsewhere—and that many of them are still in print more than a century after their original publication—suggests the persistence today of a similar and no less crippling susceptibility among millions of benign and idealistic souls around the world.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Literature, Stefan Zweig, World War II