Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Ben Michelson writes about the Mishnah’s tractate of Pirkey Avot, commonly known in English as “The Ethics of the Fathers.” Translating the Hebrew word avot as “fathers,” he says, is problematic because the early rabbis whose sayings are collected in the tractate’s five chapters “are not called avot by Jewish tradition.” Instead, Mr. Michelson suggests, avot should be translated as “principles.” This would, he believes,

follow Mishnaic usages like avot m’lakhah and avot n’zikin, and also match the content of the tractate, which deals not with Jewish law but with (ethical) principles.

I’m afraid I can’t agree. It’s true that, in rabbinic Hebrew, the word av, “father,” can also mean a general principle or rule from which secondary rules are derived, as in the two terms cited by Mr. Michelson: avot m’lakhah, “the fathers of labor”—primary categories of work forbidden on the Sabbath—and avot n’zikin, “the fathers of damage”—categories of liability dealt with by tort law. And yet in Hebrew usage avot in this sense can never stand by itself and must always be linked by the construct or possessive case to a word that follows it. You can’t say just avot if you expect it to means principles. You have to say the avot of this or the avot of that, and the avot of Pirkey Avot does not do that.

Moreover, while avot in rabbinic Hebrew often denotes the biblical patriarchs alone, it can also refer to other renowned ancestors, including the early rabbis. For example, after mentioning a halakhic disagreement between Hillel and Shammai and stating that neither man’s opinion is the accepted one, the Mishnah’s tractate of Eduyot asks: “Why, then, do we mention Hillel and Shammai [as if] unnecessarily?” And it answers: “To teach future generations that no one should think he is always right, since the fathers of this world [avot ha-olam, i.e., Hillel and Shammai] also knew they were sometimes wrong.” Translating avot in Pirkey Avot as “principles” would clearly be wrong, too.

Actually, I would have expected to be asked a different question about the translation of the words pirkey avot, whose literal meaning is “chapters of the fathers.” It’s something I’ve wondered about. Why is it that we call the work “The Ethics of the Fathers” and how did it get this English name?

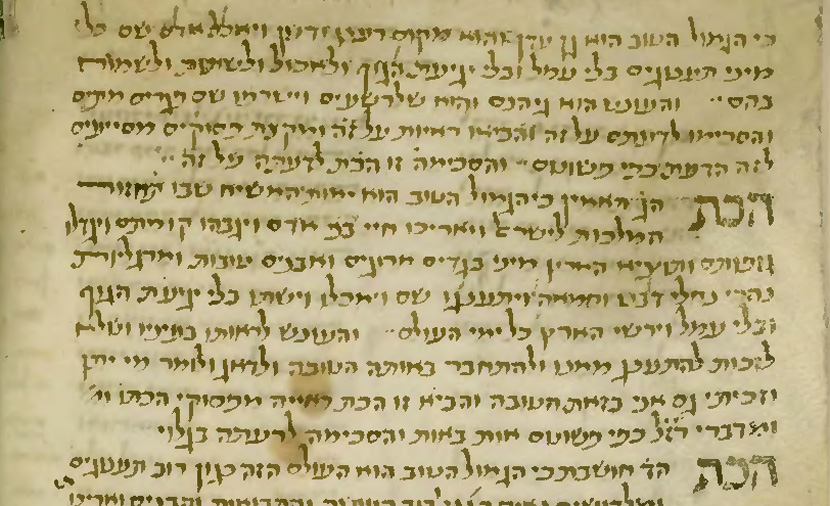

The fact is that Pirkey Avot was not always the tractate’s Hebrew name, as was pointed out by the British scholar R. Travers Herford in the introduction to his translation of it, published in 1925 as Pirke Aboth. (Sic: the “b” and “th” of Aboth reflect the assumption that these two consonants, which had such values in biblical times, were still pronounced that way by the early rabbis.) For many centuries, the work was called simply Avot or Masekhet Avot, “the talmudic tractate of Avot,” and Pirkey Avot came into use only in the Middle Ages. Pirkey gradually replaced Masekhet as the tractate was incorporated into the prayer book, in which it appears as a text to be read or studied after the Sabbath afternoon service, and came to be thought of less as part of the Talmud and more as an independent treatise.

Herford’s translation of Pirkey Avot was the work’s third into English. Preceding it were two others by British scholars, Charles Taylor’s Sayings of the Jewish Fathers, published in 1897, and W.O.E. Oesterley’s 1919 The Sayings of the Jewish Fathers. Herford, whose translation and commentary superseded both of these with readers and went through numerous printings, disapproved of their practically identical titles. “The frequent rendering Pirke Aboth by Sayings of the Fathers is quite incorrect,” he wrote in his introduction, “while Ethics of the Fathers is not a translation at all and gives a wrong impression of the intention of the work.”

Although he didn’t deny that many of the sayings in Pirkey Avot had ethical content, Herford thought that their overall purpose was to illustrate that the Mishnah was “the outcome of the labors of a great number of teachers through two centuries, some of them eminent, some obscure; that their combined work was a great act of service to God, and that all who took part were equal in that service.” He must, then, have squirmed in the grave when, his Pirke Aboth having finally gone out of print, it was reissued in 1962 by Schocken Books as The Ethics of the Talmud: Sayings of the Fathers.

Most likely, this title was suggested by Nahum Glatzer, a German-born professor at Brandeis University who was Schocken’s Judaica adviser at the time. Glatzer must have been aware of Hermann Strack’s German translation of Pirkey Avot, published in 1882 under the title Die Sprüche der Väter: eine ethischer Mischna-Traktate, “The Sayings of the Fathers: An Ethical Tractate of the Mishnah.” So, of course, was Herford, from whom we learn that by the early 20th century, “Ethics of the Fathers,” though not the title of any published book, had become, probably under Strack’s influence, a common way of referring to Pirkey Avot.

But Strack was not, it turns out, the first to “ethicize” Pirkey Avot. Before him came the Prague scholar, Orthodox rabbi, and publisher Moses Landau, whose translation of the tractate, which Strack would have been familiar with, first appeared in 1829 in a prayer book with facing Hebrew and German texts and the subtitle Die alten Gebete der Hebräer nebst Pirke Aboth oder die Ethik der Altrabbinen, “The Ancient Prayers of the Hebrews, Including Pirkey Avot or the Ethics of the Ancient Rabbis.”

In describing Pirkey Avot in this manner, Landau may have wished to counter the contention of the new movement of Reform Judaism that Orthodox tradition did not sufficiently stress ethical behavior in daily life. That the phrase was his own invention can be deduced from a reference in the prayer book’s preface to “die Pirke Aboth, die man eine Ethik der Altrabbinen nennen kann,” that is, to “Pirkey Avot, which can be called an ethics of the ancient rabbis.” He wouldn’t have put it this way if someone else had called it that before him.

Landau’s siddur, whose second, 1843 edition includes a prayer for the welfare of Ferdinand I, crowned emperor of Austria in 1835, and his wife, the empress Maria Anna Carolina, speaks of Pirkey Avot as a work to be read at home “on Sabbaths in the summer months, as a way of marking the day of rest in a useful and God-pleasing manner.” Why, you may ask, only in summer? Because in winter, when the days are short, a Jew comes home from synagogue, eats a big meal, takes a long nap, and awakes to find that it is already getting dark out. A quick afternoon prayer is all there is time for before the Sabbath is over.

For my part, I have found Pirkey Avot ideal for reading in the synagogue itself, preferably during the sermon. For sheer beauty of thought and expression, no modern rabbi comes near it.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].