Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Andrew Koss writes:

Recently, I had lunch with an anthropologist studying Soviet Jews. She mentioned the Russian phrase shakher-makher, which means shady business dealings or black-marketing, and suggested that it comes from the Hebrew word shaḥor, black, via Yiddish. I contended that this was unlikely and that it much more probably came from German Schacher, meaning haggling, particularly by Jews. (The origin of this word is a question in itself, but even if it comes from Hebrew, I can’t believe that it comes from shaḥor.) Shakher-makher could have entered Russian either via Yiddish or directly from German, courtesy of the numerous Germans present in Slavic lands. Might you be willing to settle the dispute?

Koss is correct, I believe, about shaḥor. True, shakher-makher is a good Yiddish expression, and since a makher (literally, a maker) in Yiddish, like a Macher in German, is a finagler or slick operator, the Russian meaning of “wheeling-dealing” is clearly a grammatical garbling of a prior Yiddish or German word meaning wheeler-dealer. True, too, since “black market” and its derivative of “black money” are terms relating to illegal economic activity, Hebrew shaḥor, which would become shokher in Yiddish, might be suspected of being this word.

And yet such a possibility is ruled out by two considerations. In the first place, a shokher-makher or “black-maker” would be no more idiomatic in Yiddish than in English. And secondly, both “black market” and “black money” are of 20th-century origin, whereas the shakher of shakher-makher, as we shall see, is older.

As Koss notes, Russian has borrowed over the centuries from both German and Yiddish, and it could have taken shakher-makher from either language. On the face of it, however, Yiddish is the more probable lender. For one thing, German, while having the noun Schacher and the verb schachern, to haggle or cut corners at business, does not, according to its dictionaries, have Schacher-Macher. For another, all other things being equal, Yiddish is always a more likely source than German for borrowed words having to do with shady or illegal dealings. Crime was the one walk of life in the medieval and early modern periods in which Jews and Christians cooperated closely, and many Yiddish words entered European languages via thieves’ argot. Russian slang, for example, has such words as musor, a policeman, from Hebrew/Yiddish moser, informer; ksive, a court or legal document from Yiddish ksiveh (Hebrew ktivah), writing; mlina, a thieves’ hangout, from Yiddish mline (Hebrew m’linah), a place to spend the night; and khipush, a police raid, from Hebrew (again via Yiddish) ḥippus, a search. And in Russian prisoners’ slang, a shmoneh, Hebrew for eight, denotes an inspection of prison cells, eight o’clock having been the time of day at which such inspections were held in Tsarist Russia.

Yet even if shakher-makher probably entered Russian from Yiddish, can we be sure that shakher itself was an originally Yiddish word? How do we know that German Schacher comes from Yiddish and not vice-versa—or, for that matter, that both Yiddish and German didn’t take it from Polish, in which we find the nouns szacherka, swindle, and szachraj, swindler, the adjective szachrajstwo, fraudulent, and the verb szachrować, to swindle or to cheat? And what about Ukrainian shakhrai and shakruvat, which mean the same as szachraj and szachrować, and Belarussian shakhraistva, trickery or roguery?

Obviously, we are looking at one root word that traveled among at least six different languages spoken in adjacent areas of Central and Eastern Europe. What was its initial point of departure?

If we could find a convincing etymology for the shakher of shakher-makher, we could answer that question. In the Slavic languages, there are no contenders. In German, there is Schächer, a thief or robber, from Old High German scahhari. But it is difficult to explain how a German word for thief could turn into a German word for haggling, and Schacher was considered by at least some Germans to be a Jewish word.

Writing in 1831 in an essay on the Jewish question, for instance, the German theologian Heinrich Eberhard Paulus referred to its “Hebrew origin.” And that the word was widely connected with Jews was spelled out at greater length several years earlier by the Polish scientist and author Jędrzej Śniadecki. In 1818-21, writing in the satirical magazine Wiadomości Brukawe, Śniadekci published a series of feuilletons about Polish life set in on an imaginary island called Balnibarbi. Of one element of its population, the “Szacherowie,” he wrote:

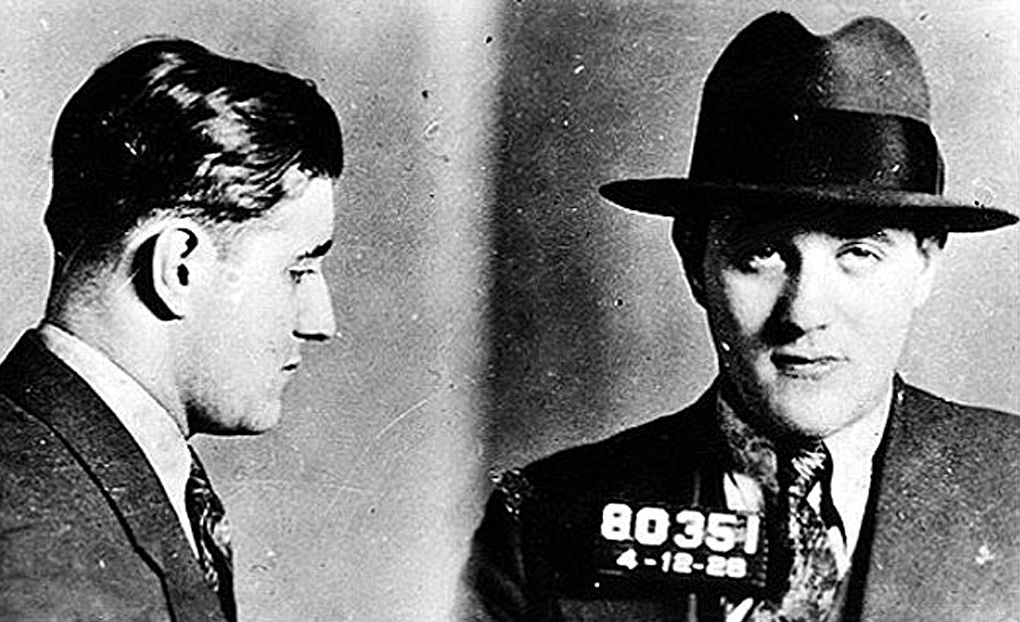

The Szacherowie are a people who have long inhabited the island of Balnibarbi. They differ completely from its other citizens in dress and in a language peculiar to themselves. They have beards and long black cloaks, and on their heads they were hats with brims broader than our bolivars. They busy themselves with clandestine trading and swindling. Even the word szacher in the local language means a downright cheat.

The Szacherowie were obviously Jews. Śniadecki, a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Vilna University, must have known some German. If by the “local language” he meant Yiddish (in Polish, as we have seen, a cheat is szachraj), he must have considered shakher an originally Yiddish rather than a German word. Where, though, could such a Yiddish word have come from? Not from soykher, Yiddish for merchant (from Hebrew soḥer), because a soykher-makher, a merchant-maker, would have no more meaning than would a shokher-makher.

Can the shakher of shakher-makher have originally been the related Hebrew word saḥar, trade or commerce? Although not an active part of Yiddish vocabulary, saḥar would have been a word known to Yiddish speakers from the Bible and other Jewish sources that would have been Yiddishized as sakher; its initial “s” could then easily have thickened to the “sh” of the shakher of shakher-makher, “trade-maker” or businessman.

Reduplicative echo formations like shakher-makher tend to have belittling meanings in many languages (think of English helter-skelter, wishy-washy, namby-pamby, etc.), and sakher-makher or shakher-makher must have had such a sense from the beginning in Yiddish, too: “You call him a businessman? Why, he’s a conniving horse trader!”

From Yiddish, shakher-makher and shakher were spread by Jews to German and various Slavic languages. And if the source of shakher is indeed saḥar, the word has been repatriated to its source in the modern Hebrew word saḥar-mekher, horse trading or wheeling-dealing, in which mekher, literally, selling, originated as a pun on the makher of shakher-makher. We even know the identity of the punster, the great Yiddish and Hebrew novelist and story writer Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh (1836-1917), better known by his pen name of Mendele Mokher Sforim.

In Israel today, saḥar-mekher is used more for politics than for business: one speaks derogatorily of the saḥar-mekher involved in cobbling together a parliamentary coalition or of getting elected mayor of a town. It’s an unusual case of a Hebrew word joined to a Yiddish one to create a Yiddish expression that was then borrowed by Russian and eventually returned to Hebrew in the expression’s Russian rather than Yiddish grammatical sense. I don’t know of another like it.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: History & Ideas, Language, Yiddish