“I am Daniel Deronda.”

With these words, Colonel Albert Edward Goldsmid, formerly of the Royal Munster Fusiliers, presented himself to Theodor Herzl in 1895 when the latter, who was soon to found the World Zionist Organization, made his first trip to England in search of supporters. There was some truth to what Goldsmid said. Like the eponymous hero of George Eliot’s 1876 novel, Goldsmid grew up as an Englishman, unaware of his Jewish origins, but ultimately returned to his people and became an early lover of Zion.

Goldsmid’s story, however, was much simpler than Deronda’s. The son of baptized Jews, he was a young officer serving in India when he first learned the truth about his background and reverted to Judaism—much as, in recent years, some Portuguese descendants of conversos have rejoined the Jewish people after uncovering their family history. By contrast, the coincidence-strewn path that leads Daniel Deronda, the ward of an English aristocrat, to the happy discovery that he is a Jew unwinds over hundreds of pages.

It all begins with Deronda’s rescue of a young waif named Mirah Cohen, who is about to drown herself. His efforts to assist Mirah in locating her long-lost mother and brother lead him to London’s Jewish East End, where he makes the acquaintance of a certain Mordecai, who is actually, as Deronda eventually learns, none other than Mirah’s brother, Ezra Mordecai Cohen.

And who or what is Mordecai to Deronda? Consumptive, not far from death, he is a Jew who clings to a vision of his people’s restoration to the Holy Land. This vision he struggles to transmit to Deronda, of whose own Jewishness Mordecai is almost completely convinced despite the latter’s honest but ignorant demurrals. Still, before he has any inkling of his own true identity, Daniel does figure out the two siblings’ relationship and succeeds in reuniting them. In the course of doing so, he falls in love with Mirah.

Not long afterward, the unrelated intervention of a friend of Daniel’s grandfather induces the Jewish mother whom Daniel has never met to summon him to Genoa, where she explains the lengths to which she has gone to spare him the burden of Jewishness. To her dismay, but not to the reader’s surprise, Daniel proclaims himself glad and proud to learn that he was born a Jew.

Upon returning to England, Daniel shares the good news with his new Jewish friends. Mordecai dies shortly afterward, content that he has breathed his soul into Daniel, and the novel ends with the newlywed Daniel and Mirah heading east together to fulfill Mordecai’s Zionist dreams. As the novel is set during the time in which Eliot was writing it, Daniel and Mirah would have moved to the land of Israel roughly two decades before Herzl would come to write The Jewish State.

So this, in a nutshell, is the story of Daniel Deronda. But it is by no means all there is to George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, an 800-page novel of which the tale of Daniel’s Jewish and Zionist initiation constitutes but a part. Indeed, in the eyes of one prominent 20th-century literary critic, the Jewish component of the book was wholly dispensable. The illustrious Cambridge professor F.R. Leavis dreamed of “freeing by simple surgery the living part of [this] immense Victorian novel from the dead weight of utterly different [that is, Jewish] matter that George Eliot thought fit to make it carry.”

And what was that “living part”? Specifically, Leavis proposed to sever, from the story I’ve just summarized, the “compellingly imagined human truth of Gwendolen Harleth’s case-history” and make it into the core of a presumably renamed novel. But who or what is Gwendolen Harleth to Daniel Deronda? A vivacious, alluring young woman suddenly reduced from a coddled existence to one of “poverty and humiliating dependence,” Gwendolen has been maneuvering to claw her way out through a marriage of convenience to a wealthy aristocrat she knows is unworthy of her. Her life intersects with that of Deronda already in the novel’s first pages, but they do not converse with each other until halfway through. As Gwendolen’s wretched marriage becomes more and more excruciating, Deronda becomes at first her moral adviser and then the object of her strongest affections. But not even the fortuitous death of her husband can bring him within her reach.

Apparently unimpressed by Gwendolen’s sad story, the book’s first Hebrew translator, David Frischman, made it his business, as Gertrude Himmelfarb has observed, to perform Leavis’s surgery “in reverse” by publishing a Hebrew edition “without the Gwendolen distraction.” Indeed, many appreciative readers of Daniel Deronda, even if they have never entertained the thought of operating on it, have found themselves wondering about the relationship between its two rather disparate parts.

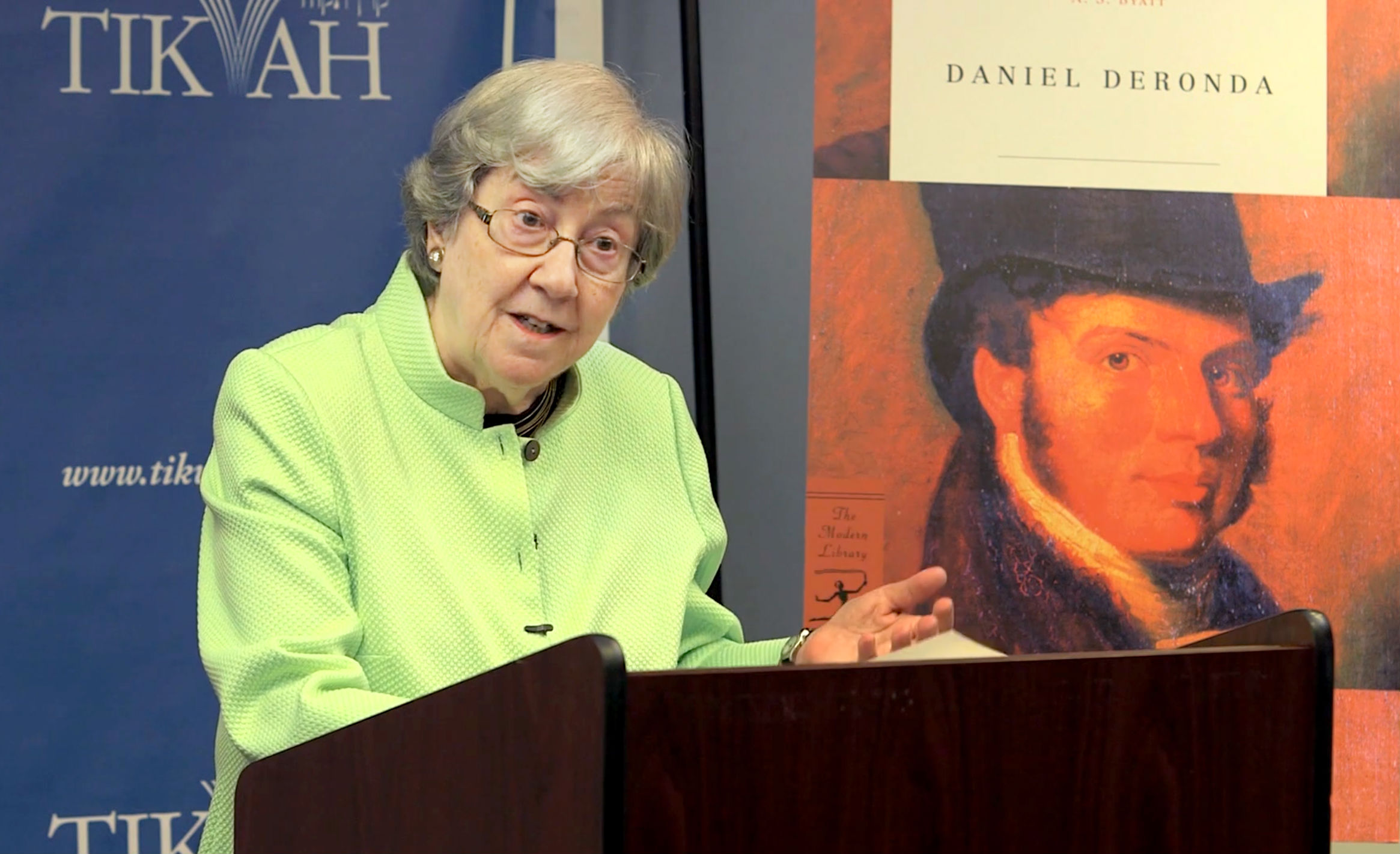

For such people, and for those who have yet to open this novel—or to see the 2002 BBC serial based on it—precious help is now at hand. In an eight-part lecture series produced by the Tikvah Fund, Ruth Wisse, the emerita Harvard professor of Yiddish and comparative literature, explains, sometimes from a bench in New York’s Central Park and sometimes from behind a lectern, just what George Eliot’s last novel is all about and, among many other things, why Gwendolen Harleth and Daniel Deronda really belong between the covers of the same book.

Above all, Wisse observes that George Eliot was “a philosopher who chose the novel as her medium.” This not to say that we can tease out the meaning of Daniel Deronda by elucidating the philosophy that underlies it. Wisse certainly doesn’t think so. Rather, proceeding in the opposite direction, she demonstrates, step by engaging step, how Eliot’s philosophical teaching emerges through, precisely, the interaction of the diverse fictional personages who populate her pages.

To obtain maximum benefit from this exercise, viewers of the series who have already read the novel will be in an advantageous position. But any and all will benefit from the drama on the screen. True, in the 400 or so minutes of the series we barely catch a glimpse of anyone other than Professor Wisse (although now and then we hear the students in her classroom murmuring or laughing in agreement with her). But there’s enough excitement in watching the real-life character of Ruth Wisse, the master explicator and ardent, lifelong Zionist, as she relates to the fictional characters in Daniel Deronda and to the real if long gone woman who created them. If you just read a printed transcript of “Ruth Wisse on Daniel Deronda,” you would miss a great deal. The treat lies in the viewing.

Wisse begins where the novel begins, with Gwendolen Harleth. As she observes, no one could fail to be moved by the story of this “spoiled child,” as the subtitle of the first of the novel’s eight books identifies her. But what does Gwendolen’s problem have to do with the Jewish problem? Nothing directly, Wisse tells us, but everything indirectly. Gwendolen symbolizes the English problem, as George Eliot saw it, in the eighth decade of the 19th century—and this problem, in the novelist’s eyes, was thoroughly intertwined with the Jewish one.

In terms of the novel’s overall message, what’s most important about Gwendolen is what she lacks. It’s not just money, or good options in life. Rather, the spoiled child has developed into a woman who “had never dissociated happiness from personal pre-eminence and éclat.” This is what makes her sudden descent so hard. But the still “deeper source of disturbance within her,” Wisse tells us, is the fact that “she is not really rooted in the place of her birth or in the traditions from which she derives.”

To substantiate this point, the third video highlights the following observation by Daniel Deronda’s narrator (Book I, chapter 3):

A human life, I think, should be well rooted in some spot of a native land, where it may get the love of tender kinship for the face of earth, for the labors men go forth to, for the sounds and accents that haunt it, for whatever will give that early home a familiar unmistakable difference amid the future widening of knowledge: a spot where the definiteness of early memories may be inwrought with affection, and kindly acquaintance with all neighbors, even to the dogs and donkeys, may spread not by sentimental effort and reflection, but as a sweet habit of the blood. . . .

These words, Wisse observes, describe “the familial and national rootedness that this book considers healthy for human development”—precisely the rootedness of which Gwendolen had been deprived. And Gwendolen, Wisse goes on to note, “is likewise without any religious upbringing.” Thus, the biography of the novel’s heroine reflects how, in late-19th-century England, “religion and family stability were being eroded with so far no better structures or cultural values to replace them.”

If Gwendolen’s character mirrors that of her country, so do her prospects. For her personal future and character, Wisse says, are tantamount to “the future and nature of England.” Gwendolen eventually becomes enamored of the novel’s hero, Daniel Deronda—whose own, newfound Jewish attachments will preclude their union. But “how Gwendolen will react to being rejected by Deronda” will in turn tell us whether “England can ever accept the distinctiveness of the Jews.” This, moreover, was a matter of vital importance, for, in George Eliot’s view, “to learn to appreciate the Jews was to save England from perdition.”

Putting the Jews themselves on the road to salvation was to be the main task of Daniel Deronda himself. Even those who have not read the novel are likely to recognize the hero’s name as that of a precursor of the Zionist movement: a fictional counterpart of such real-life 19th-century advocates of the Zionist idea as Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai, and the German-French socialist philosopher Moses Hess.

Indeed, as Wisse observes, Mordecai, the character in the novel who becomes Deronda’s mentor, serves as something of a mouthpiece for the proto-Zionist philosophy that, only a little more than a decade prior to the publication of Daniel Deronda, Moses Hess had set forth in Rome and Jerusalem: a book with which George Eliot herself was quite familiar and of which she clearly approved. Let’s listen to Mordecai as he preaches to skeptical Jewish friends gathered in “The Philosophers’ Club” (Book VI, chapter 42):

Revive the organic center: let the unity of Israel which has made the growth and form of its religion be an outward reality. Looking toward a land and a polity, our dispersed people in all the ends of the earth may share the dignity of a national life which has a voice among the peoples of the East and the West—which will plant the wisdom and skill of our race so that it may be, as of old, a medium of transmission and understanding. Let that come to pass, and the living warmth will spread to the weak extremities of Israel, and superstition will vanish, not in the lawlessness of the renegade but in the illumination of great facts which widen feeling, and make all knowledge alive as the young offspring of beloved memories.

There’s no need to dissect the congeries of ideas here expounded in somewhat obscure fashion. For our purposes, we need only note the distinction, drawn incisively by Wisse, between the relatively muted effect those ideas had when set forth in Hess’s philosophical tract and their considerably greater impact when embedded in a fictional narrative and in the impassioned spirit of their flesh-and-blood proponents. This much is plain enough to any reader of the book, but in the videos Wisse also points out a host of things that could easily escape a reader’s notice—including the way in which the mere presence in the hall of a gentleman like Daniel Deronda lends greater force and suasion to Mordecai’s argument as he expounds it to the assembled “philosophers.” Indeed, Hess’s Rome and Jerusalem was completely forgotten by the time of the First Zionist Congress in 1897. Meanwhile, George Eliot’s novel, as the Israeli scholar Shmuel Werses has documented in compiling all of the contemporary references to Daniel Deronda in Hebrew literature and the Hebrew press, had attained a near-mythic status among Jewish readers in the years prior to Herzl’s advent.

Wisse rightly emphasizes how strongly George Eliot herself supported Mordecai’s insistence on the need for Jews to reclaim the “dignity of a national life” and his call for a return to their homeland. But the question has to be asked: was Eliot really in complete accord with her proto-Zionist prophet? Certainly nothing in the novel suggests otherwise. But the novel isn’t the only medium in which she chose to express her view of things. In an 1879 essay titled “The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!” (a reference to the pogroms that swept through Germany in 1819), composed at the same time that the term anti-Semitism was coined in Europe, Eliot brilliantly plumbed the depths of that cancerous phenomenon in its modern guise. In the same essay, as Ruth Wisse insightfully demonstrates in the final episode of the video series, Eliot also meditated on the relative value of nationalism in general: not only its undoubted merits but the threats to its perdurance and its own vulnerability to harmful distortion or disfigurement.

Only membership in a national community, Eliot wrote in her 1879 essay, supplies the ordinary person with an otherwise unattainable “sense of special belonging which is the root of human virtues, both private and public.” But these critically indispensable feelings were being steadily undermined by ongoing cultural changes. The change Eliot most feared, curiously enough, was “the tendency of things . . . toward the quicker or slower fusion of races.” In fact, she judged this tendency “impossible to arrest”:

[A]ll we can do is to moderate its course so as to hinder it from degrading the moral status of societies by a too rapid effacement of those national traditions and customs which are the language of the national genius—the deep suckers of healthy sentiment. Such moderating and guidance of inevitable movement is worthy of all effort. And it is in this sense that the modern insistence on the idea of nationalities has value.

Reading Daniel Deronda in the light of these utterances, one might be tempted to speculate that George Eliot’s Zionism, as wholehearted as it undoubtedly was, may have been motivated at least in part by a worry that England itself lay in danger of an “effacement of [its] national traditions and customs” from, among other factors, the presence of increasing numbers of Jews who had been settling there in recent years. Is that why she shared Mordecai’s and Daniel’s enthusiasm for the ingathering of the Jews in their national homeland, and why she deemed this could have a salutary impact on both England and the whole world?

Some critics have indeed argued that darkly “racialist” impulses of this kind can be perceived at work in Eliot’s ardent nationalist pronouncements. But against them one must register her keenly realistic recognition of the excesses to which nationalism itself can lead. If she feared a future in which all national differences would eventually dissolve, she positively dreaded the development of xenophobia in England—and its menacing implications for lately arriving Jews. By the same token, she made sure to have her fictional hero Daniel Deronda espouse a liberal variant of nationalism for his new homeland. The flexible and resonant formula he announces for the future Jewish nation is a twist on a slogan adopted by his pious grandfather, whom he had never met: “separateness with communication.”

That moderating flexibility applies to domestic relations within the envisioned Jewish nation no less than to relations between it and other nations. Internally, as Ruth Wisse tells us, Daniel declines not only the path of Reform Judaism, with its firm rejection (at that time) of Jewish nationality, but also “the path of defensive Orthodoxy.” Externally, Wisse sums up in Episode 8, he claims

the right to live as a Jew in contact with other peoples. And perhaps, if his grandfather [had] emphasized the separateness in the phrase “separateness with communication,” [Daniel] will emphasize the qualifier: with communication. So this principle of separateness with communication is no less prominent an idea [in the novel] than the idea of Jewish nationalism itself. And it also pertains equally to the British and the Jewish parts of the novel—and offers the rationale for their coexistence.

On this note, we’re back to where we began, which may be a good place to leave things. Although I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of Ruth Wisse’s rich discussion of Daniel Deronda, my purpose has been to provide not a brief substitute for a great performance but something more like a trailer. I hope I’ve convinced you that the series is a must-see—and that, if you haven’t already read the book, I’ve aroused your determination either to read it first for maximum enjoyment of the show or at least to keep a copy close at hand as you partake of this sympathetic, attentive, and high-spirited intellectual tour de force.

More about: Arts & Culture, Daniel Deronda, George Eliot, History & Ideas, Literature, Ruth Wisse