Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

It happens every year: Purim is back with the book of Esther, the Bible’s only situation comedy. Like some old Hollywood movies, the story combines a ridiculous plot with sparkling dialogue as cool, clever Mordecai and brave, beautiful Esther foil evil Haman and bumbling Ahasuerus.

Poor Ahasuerus! A buffoon in the Bible, he’s become an icon of male sexism for our contemporary Vashtians. He doesn’t deserve such opprobrium. What, after all, did he do? Publicly shamed by a wife who refused to circulate among the guests at a party that he threw, he chose to relieve her not of her head, as was his royal prerogative, but merely of her job. By the standards of the times, he was a progressive.

The Ahasuerus of my present, Purim-inspired column, however, is not the Ahasuerus of the book of Esther. You didn’t know there was another? Listen to a story.

In 1602, a German author with the probably pseudonymous name of Chrysostomos Dudulaeus Westphalus—that is, Chrysostomos Dudulaeus of Westphalia—published a book entitled Kurtze Beschriebung und Erzehlung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasveros, “A Brief Description and Tale of a Jew by the Name of Ahasuerus.” In it he cited at length the account of one Paul d’Eitzen, a theologian and (prior to the Reformation, which he joined) Catholic bishop who, while attending church in Hamburg in 1547, noticed a man listening to the sermon and bowing low “with great humility” at each mention of Jesus. “Of tall stature, with bare feet and long hair falling to his shoulders,” the man was approached by d’Eitzen after the service. He told him that his name was Ahasveros; that he was a shoemaker by trade; that he had lived in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus’ crucifixion; that he had stood in his doorway as Jesus passed by carrying the cross; and that he had mockingly told Jesus to hurry up and walk faster, whereupon Jesus had said to him, “I will stop here to rest but you will keep walking until the Last Judgment.”

In the millennium-and-a-half since then, Ahasveros told d’Eitzen, he had wandered the world without dying, going from place to place and country to country while waiting for Jesus to come again. A devout Christian as a result of his experience, he was, d’Eitzen is quoted by Chrysostomos as saying,

quiet and reserved. He rarely talked except to answer questions put to him. When he was invited to a meal, he ate little and soberly. He was always in a hurry and never stayed in one place long. In Hamburg, Danzig, and elsewhere, he was offered money, but he never accepted more than two groats which he immediately gave to the poor, saying that God looked after him, that he had repented of his sin, and that God had pardoned him because it was committed in ignorance. During the time he spent in Hamburg and Danzig, he was never seen to laugh or smile. . . . He could not bear to hear anyone blaspheme or swear by God’s Passion. At such times, he grew angry and morose.

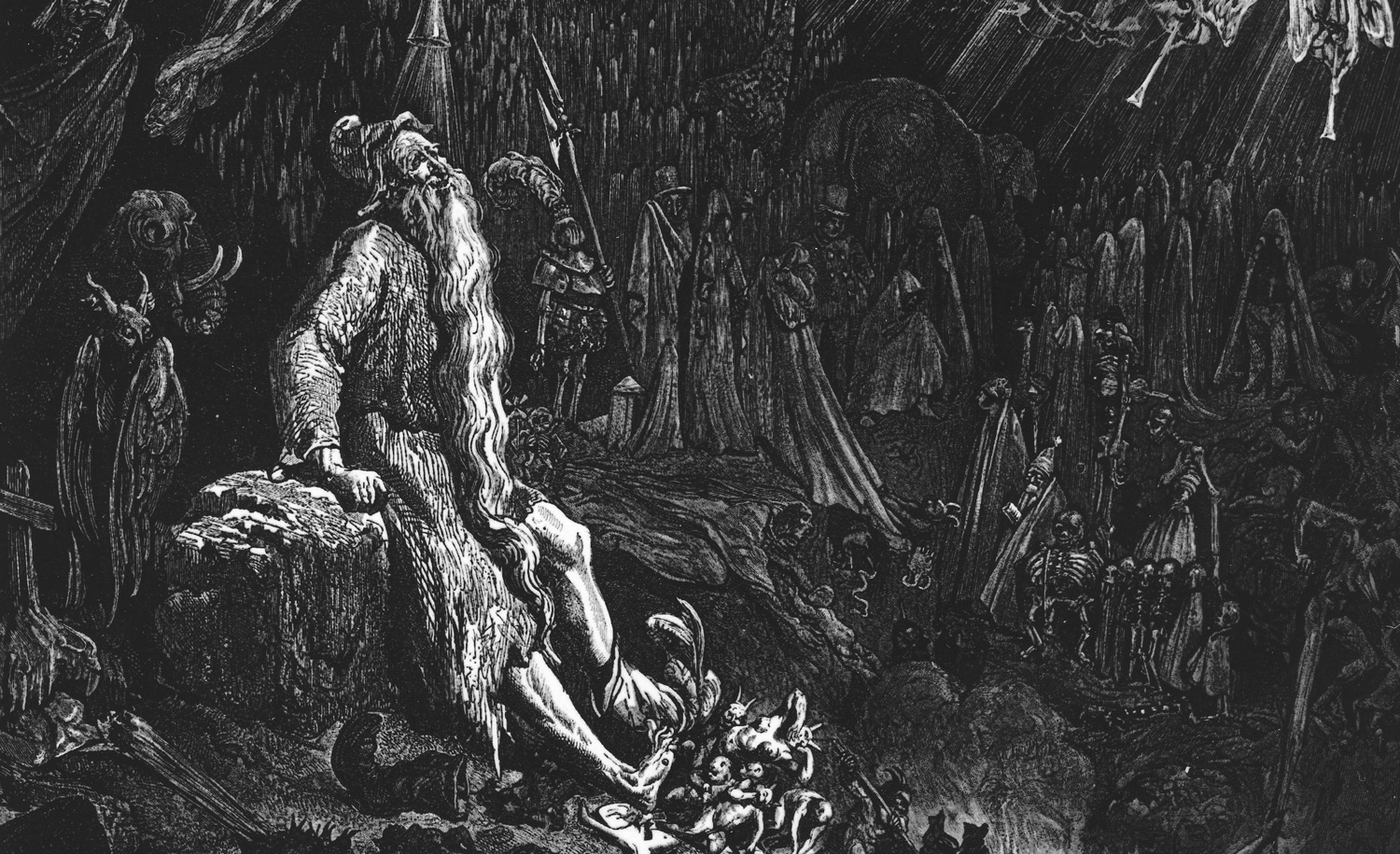

Chrysostomos Dudulaeus’ book was an immediate best-seller and went through numerous editions in many languages. Ahasveros, who also came to be known as “the Eternal Jew” or “the Wandering Jew,” caught the imagination of Christian Europe. New sightings of him kept being reported. He became the subject of popular ballads, operettas, poems, stories, novels, and plays. He variously came to symbolize the accursed Jewish people, the redeemable Jewish people, the always present historical observer, and the tragic plight of immortality. The young Shelley wrote a long poem about him. Both Goethe and Pushkin tried unsuccessfully to do the same. He was the protagonist of Ernst Klingemann’s play Ahasver, Hans Christian Anderson’s story “Ahasuerus,” and Eugène Sue’s novel Le Juif Errant. He appeared in stories by Hawthorne and Mark Twain. The French artist Gustave Doré did a series of illustrations of him. A character in Wagner’s opera Parsifal was a female version of him. In times closer to our own, he has been the subject of Pär Lagerkvist’s novel The Sybyl, Machado de Assis’ story Viver!, and Borges’ story “The Immortal”—and the list is partial.

This leads one to ask: why the name Ahasuerus? What connection is there between the legend of the Wandering Jew and the doltish king of the book of Esther? And if there isn’t any, what made Paul d’Eitzen or Chrysostomos Dudulaeus choose the name? Whether as the Christian Bible’s Ahasuerus or (in Martin Luther’s German translation) as Ahasveros, the Persian Axšoreš, the Hebrew Aḥashverosh, or the Greek Xerxes, it certainly wasn’t a name that any Jew or Christian ever went by. Not even the scholars can help. None that I know of has offered an explanation.

Not having a scholar’s responsibilities, I’ll venture a guess. First, though, let’s take a look at what is known about the story’s background.

Legendary figures who never died can be found in both Jewish and Christian tradition. Best-known in the former is Elijah, who, according to the Bible, ascended “heavenward in a chariot” and became in Jewish lore a miracle worker appearing in every generation to succor the poor and downtrodden. In Christianity there is the apostle John, Jesus’ most beloved disciple, promised at the Last Supper that he would live to see the Second Coming. But there are less blessed immortals in Christian folklore, too. In a study of the Ahasuerus story, the great 19th-century French scholar Gaston Paris wrote about one of them:

An Italian legend that must be considered very old tells of a Jew named Malc who gave Jesus [while on his way to be crucified] a slap with an iron glove; in punishment he was condemned to go on living on earth and to turn ceaselessly around a pillar (no doubt the pillar from which Jesus was hung), so that he sank into the soil. In despair he banged his head against the pillar, but he was unable to die because he had been sentenced to suffer in this manner until the Last Judgment.

Malc, also called Malchus, Marc, or Marcus, was a personification of the Christian belief that the Jews were eternally cursed because of their role in crucifying Jesus; as such, he was a distant forerunner of Chrysostomos Dudulaeus’ Ahasveros. Less distantly, according to the English monk Matthew of St. Alban, a nameless Armenian archbishop, while on a visit to England in 1228, related having met a man, originally named Cartaphilus, who had been the Roman procurator Pontius Pilate’s doorman when Pilate sentenced Jesus to death. Striking Jesus with a fist as he was bent beneath the cross, he said to him, “Get going, Jesus! Why are you so slow?” To which Jesus, “looking at him severely,” replied: “I will go but you will await me until I return.”

Cartaphilus, according to Matthew of St. Alban, then repented, became a Christian, changed his name to Joseph, and was living a saintly life in Armenia when encountered by the archbishop. A Roman in Matthew’s account, he was soon Judaized by the French chronicler Philippe Mouskes, who also claimed to have spoken with the Armenian archbishop. Joseph, Mouskes wrote in 1243, was one of “the perfidious Jews” who exultantly ran to witness Jesus’s crucifixion. Fated to live until Jesus’s return, he was miraculously rejuvenated every hundred years and started life again as a young man.

But the Joseph-Cartaphilus story didn’t begin with Matthew of St. Alban. Five years earlier, in 1223, the Italian astrologer Guido Bonatti reported having met a man named Johannes Buttadeus who “lived at the time of Jesus Christ and struck the Lord as he was being led to the pillory, and he [Jesus] said, ‘You will wait for me until I come.’” In the centuries that followed, Bonatti’s story circulated widely in Europe; Buttadeus’s Latin name was changed to Giovanni Bottadio in Italian, Jean Boutedieu in French, and other variations elsewhere. In some versions of the story, such as an early 15th-century account by the Italian Antonio di Francesco di Andrea, Giovanni Battadio is credited with working Elijah-like miracles and knowing the future. Di Andrea claimed to have run into him in the Alps and to have seen him save travelers stranded in the snow.

Although popular etymology explained the names Bottadio and Boutedieu as coming from Italian battere and French bouter, “to strike,” and Italian Dio and French Dieu, “God,” Gaston Paris established that the name was in fact a garbling of Latin Johannes devotus Deo, “John the devotee of God,” and that it conflated two motifs: that of John the apostle and that of the Wandering Jew. This was reflected, Paris wrote, in the Spanish version of the story, in which Johannes Buttadeus was called Juan de Voto a Dios, “Juan of I-vow-to-God,” Latin devotus having been corrupted to Spanish de voto.

I hope you’re still with me, because we’re getting there. Juan de Voto a Dios had another Spanish name, Juan de Espera en Dios, “Juan of Wait-for-God,” an allusion to Psalms 27: 13-14, which reads: “I believe that I shall see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living. Wait for God! Be strong and let your heart take courage! Yea, wait for God!”

This name, too, originally referred to John the apostle and was later transferred to the Wandering Jew, in which guise it turns up more than once in 16th- and 17th-century Spanish literature. To take one example: in Francisco Delicado’s picaresque novel Retrato de la Lozana andalusa, published in 1528, the heroine Lozana, referring to the Wandering Jew’s ability to predict the future, states that if she knew certain things, sabría mas que Juan de Espera en Dios, “I would know more than Juan de Espera en Dios.” Spanish readers obviously knew who that was.

And now for my guess. Suppose that either Paul d’Eitzen or Chrysostomos Dudulaeus had encountered the name Juan de Espera en Dios as that of the Wandering Jew without knowing what it meant; and suppose, too, that one of them was struck by the similarity in sound between “Huandespera” and Ahasveros (the Spanish “j” was already pronounced by the 17th century as the guttural “h” that it is today); might not he have thought he was hearing the name of the Persian king or a garbled version of it? And might not he have decided that Ahasveros was the Wandering Jew’s true name, or simply that it was the name that he would give him? Can we rule that out?

I wouldn’t—at least, not until a better explanation comes along.

Have a merry Purim!

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: History & Ideas, Purim