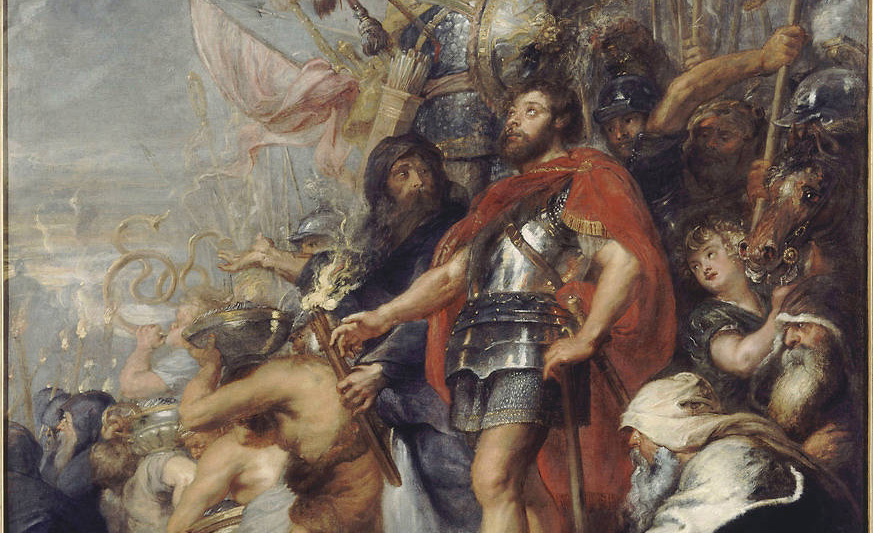

From The Triumph of Judas Maccabeus by Peter Paul Rubens, 1635.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Hanukkah, the celebration of the victory of the Maccabees, is here again, and with it the old conundrum of what the word Maccabee originally meant. Here’s a modest suggestion for a new way of thinking about it.

First, though, I should point out that the use of the word “Maccabees” for the successful 2nd-century-BCE Jewish rebels against Syrian Greek rule derives from a misunderstanding. At the time of their uprising, there were no Maccabees. They and the royal house they established were known to their Hebrew- and Aramaic-speaking compatriots in Palestine as the Ḥashmona’im, the Hasmoneans, after the revolt’s first leader, Matityahu ha-Ḥashmona’i, whose five sons headed it after his death. The source of “Hasmonean” is uncertain; most likely Ḥashmona was the name of either an ancestor in Matityahu’s family or of a place from which the family hailed.

As related by the Oxford New English Bible’s translation of the Greek text of the first book of Maccabees, itself a translation of a lost Hebrew account of the revolt written by a near contemporary:

And Ioudas, who was called Makkabaíos, rose up in [Matityahu’s] place, and all his brothers helped him, as did all who had joined his father. . . . And he spread glory to his people, and put on his breastplate like a giant, and strapped on his war instruments. And he conducted battles, protecting the camp by the sword.

Originally, then, the only Maccabee was Ioudas Makkabaíos or, in Hebrew, Yehudah ha-Makkabi (with the syllabic stress on the final vowel of “Makkabi”); Judah’s four brothers all had epithets of their own. Early in the Christian era, however, 1Maccabees was given the Greek title, in reference to Judah’s exploits, of to Biblion ton Makkaibaíkon, “The Book of Things Maccabean” (in Latin, Liber Machabaeorum). And since Makkabaíkon, “Things Maccabean,” was in the genitive plural, later ages mistakenly took it to refer to the first generation of Hasmoneans as a whole. Hence, Maccabee became also a term for any of Judah’s followers rather than just for Judah alone. Its first recorded use in this sense was by the Christian church father Tertullian toward the end of the 2nd century CE.

But to get back to our opening question: what did makkabi, which occurs nowhere in the Bible or in early rabbinic sources, mean? And was the word originally spelled מכבי with the Hebrew letter kaf, which is how it is written today, or rather with a kuf as מקבי?

In a 2011 article on the subject, Mitchell First argues persuasively, based on an analysis of ancient Greek and Latin orthography, that the kuf spelling is the older one. He also agrees with the now commonly accepted theory, first put forth by the American Bible scholar Samuel Ives Curtiss, Jr. in 1876, that makkabi derives from Hebrew makevet or its Aramaic cognate makava, a hammer or mallet. First writes:

As to why Judah was called by this name, one view is that the name alludes to his physical strength or military prowess. But a makevet/makava is not a military weapon; it is a worker’s tool. Therefore, it has been suggested alternatively that the name reflects that Judah’s head or body in some way had the physical appearance of a hammer. Interestingly, the Mishnah at B’khorot 7:1 lists one of the categories of disqualified priests as ha-makavan [“the hammerhead”], and the term is explained in the Talmud as meaning one whose head resembles a makava. Naming men according to physical characteristics was common in the ancient world.

The derivation of makkabi from makevet or makava certainly makes better sense than any of the contending explanations. What I would take issue with is the assertion made by First and others before him that since a hammer “is not a military weapon,” Judah Maccabee must have been likened to one because of his physical appearance, or else because of his physical power or strength of character.

The fact of the matter is that in both ancient and medieval times, hammers were military weapons. First himself mentions the French warrior Charles Martel, “Charles the Hammer,” the grandfather of Charlemagne, best known for stemming the Muslim advance into Europe at the Battle of Tours in 734. While this epithet, too, may have referred only to Charles’s prowess as a commander, the martel de fer or “iron hammer” was a feature of medieval warfare. Typically, it was mace-like or club-like at one end and pointed like a pickax at the other, and it was most commonly wielded by mounted cavalry to smash the armor of enemy soldiers.

True, Judah Maccabee was not a medieval horseman—but the martel de fer, under different names, goes back much farther than the Middle Ages. Known as a koryn, it was already used by the ancient Greeks in Homeric times, as is attested by a passage in Homer’s Iliad. There, in Book VII, we read about King Areïthous, whom “men and fair-girdled women were wont to call the mace-man, for that he fought not with bow or long spear, but with a mace of iron broke the [foe’s] battalions.” Homer’s word for “mace-man” is koryntes, a soldier equipped with a koryn.

Is it not then likely that Yehudah ha-Makkabi was Ioudas ho Koryntes or Judah the Mace-man? The very fact that maces do not seem to have been standard equipment among Judah’s soldiers—at least, they are not mentioned in accounts of their battles in Maccabees I and II—would have been a good reason, as it was in Homer’s day, to single out by name someone who fought with them, especially since attacking an armored, sword-bearing enemy with a mace would have called for great strength and courage.

Not that a mace-man wouldn’t have had a sword as well. We are told that Judah did, and that he “strapped on his war instruments,” which means that he went into battle with several, just as a World War II infantryman might have carried a rifle over his shoulder, a bazooka on his back, and a hand grenade in his pouch. Still, while the mace was being swung the sword could not have been brought into play; at such a moment, Judah would have had to depend on his heavy leather or metal breastplate—which he wore, we are told, “like a giant”—for protection.

It’s certainly more flattering to think of Judah as a mace-man than as a hammerhead. Why couldn’t the hero of Hanukkah have been both brave and good-looking?

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].