We present here the first chapter from the memoirs-in-progress of the renowned scholar and author Ruth R. Wisse. Further installments will appear regularly over the next months.

Ruth Wisse’s books include The Modern Jewish Canon, A Little Love in Big Manhattan, If I Am Not for Myself, No Joke, and Jews and Power. A Hebrew edition of Jews and Power is about to be released by Toby Press in Israel.

It was not easy for a European Jew to beat the odds in the mid-20th century. When in my teens I began reading accounts of those who did, I wondered how I would have fared had I been in their place. Some who became known as “survivors” ascribed their endurance to qualities of mind and spirit; others denied that any special talent or action could explain it.

The art of writing that sustained Anne Frank in her secret attic proved useless once she was shipped to Bergen-Belsen. The intellectual Jean Améry, born Hans Meyer—one of the eyewitnesses I most trust—not only denied the advantage of rational-analytic thinking in Auschwitz but described the ways in which, by reconciling the inmate to the system of his destroyers, such thinking could induce a “tragic dialectic of self-destruction” (my emphasis). We have no depositions from the absent majority of Jews who could not determine their fate. Only the Allied victory permitted those who made it through the war to record their stories, an exercise that itself can tend to magnify the power of personal agency in forging personal fate.

I was four years old when my parents engineered our escape from Europe, so I cannot pretend to have had a big hand in the matter. Had they not managed our flight in the summer of 1940, I would have remained a cute photograph in some Holocaust memorial museum. As we say in Yiddish, moykhl toyves—spare me those favors. I’m not a great fan of Holocaust memorials and don’t much care about the posthumous compassion of strangers. I just wanted to live. But having escaped the ash heap, I remain curious about the ratio of accident to enterprise in our own successful exodus.

Whose idea was it to leave? How close did we come to failure? And was I more an asset or a liability? None of the escape was my own doing, but would we have made it had I not been fortuitously groomed for such an eventuality? These, at least, are the questions I’ll try to illuminate and perhaps even answer in the story I tell here.

I

In a drawer alongside my expired and current passports is a snapshot of the page in the 1936 city register of Czernowitz—then in Romania, presently Ukraine—that lists Rut, female of the Mosaic faith born on May 13 to Leib Rojskiss engineer (age thirty) and Masza Welczer housewife (age twenty-nine) residing at 43 Yarnic Street. My younger brother David, who recently looked up the Czernowitz register when he visited the city as part of his research into our family history, brought me this souvenir. He knew I might not be keen to make the trip myself. Although I’m the only surviving member of our family who’s originally from Czernowitz, I was always much more interested in exploring Vilna and Bialystok, respectively the Polish birthplaces of our mother and father, than in revisiting mine. I have never yet returned to today’s Chernivtsi and doubt that I shall.

Mother enjoyed telling me about my birth; it was one of her few stories that I could not get enough of. On a lovely day in May, she was standing by the window of her bedroom looking out into the garden where the landlord, Mr. Vinovic, was trimming the bushes. When he caught sight of her at the open window, he asked would she like some flowers? She said yes, thank you, and then went into labor so quickly that I was born by the time he arrived with a bouquet.

So I always thought of myself as born on a bed of roses (minus the thorns, and who said it was roses?) in a sunny bedroom with a cheerful midwife tending to a joyful mother. Just to show how incurious I can be when I put my mind to it, I retained this image of my mother’s effortless delivery of me even after my discrepant (and more common) experience in giving birth to three children of my own.

Apart from Mr. Vinovic and the midwife, no one else featured in Mother’s account of that sunny day, not my father or my older brother Benjamin who had just turned five and must have been more than usually concerned about the arrival of this little sister. In addition to the usual reasons for fearing the arrival of a new sibling, Ben had lost another younger sister before me—Odele, who died of meningitis at age two. Mother told us of being so distraught in the last stages of Odele’s illness that she couldn’t enter the sickroom to sit beside her dying child. She thought to spare Ben by never telling him that his sister was dead, hoping he would accept their explanation that she had “gone away” and stop asking about her, as he eventually did (possibly to spare the adults). When I then arrived two years later, he would surely have wondered how long I intended to stay around.

It was different for me, who never knew a world without the assurance provided by Ben—a story in itself, which I hope to tell at a later date. But our parents must have been happy to have another daughter to replace the beautiful child they had lost. “Replace” isn’t the right word, though: Mother always kept Odele’s portrait on the wall beside her bed, the child standing guard over the mother who could not save her. Our baby pictures in Mother’s photograph album look so much alike that I could not distinguish between my absent sister and myself until the blond little girl in the picture became older than two.

Though no one ever compared me explicitly with Odele, her death hugely affected my life. Whether Mother no longer trusted herself to raise a child, or because it hurt too much to be reminded of the missing one, when I was born she hired a nanny who then stayed on as my governess. This guvernantke slept in my room, saw to my needs, and relinquished me to the rest of the family at appropriate times, so that I readily identify with children of royalty who are raised from birth with expectations of disciplined behavior and high performance in return for the unlimited care and comfort they receive.

Royals are required to prove themselves worthy of the benefits bestowed upon them. Mother’s (obviously flawed) recollection that I was toilet-trained at six months reflects Nanny’s perfect discipline rather than mine, but also accounts for my patrician sense of duty. That is partly what I mean by being prepared for an eventuality: I was raised to be flawless, which would then mean behaving like a self-controlled adult.

Czernowitz had been part of the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian empire, and stayed polyglot when it became incorporated into Romania after World War I—polyglot, but no one pretended that its various languages enjoyed equal status. German remained the tongue of distinction as it did in Prague, another multilingual city of East Central Europe. Jews adapted linguistically in order to function economically and survive politically. If the Czernowitz elite spoke German, so, too, did its Jews, and since our parents had become part of the Czernowitz Jewish elite, they prepared their daughter to join its ranks.

Thanks to my nanny Peppi, a German-speaking Jew from Czernowitz who remained a professional governess all her life, I spoke German impeccably. She imparted it so well that heads were said to turn in the street when people overheard me conversing with her. When a visiting friend of Mother’s tried to stop me from following her into the bathroom, I assured her that women need not feel ashamed in one another’s presence, “Frauen zu frauen dürfen sich nicht schämen.” Stories about children often feature such cheekiness; Mother’s anecdotes about me also turned on the fluency in German that distinguished me from our Yiddish-speaking parents and from Ben, who attended a Romanian elementary school.

In his Memoirs of an Anti-Semite—the title’s admission of bigotry is meant to enlist our trust—my Czernowitz landsman, the German novelist Gregor von Rezzori, gives us his impression of one of his Jewish mistresses:

But her language, as I was saying: her sing-song, the flattened vowels, the peculiar syntax of people who, although having known an idiom since childhood (in her case, Romanian), remain alien to it, and then the Yiddish expressions interjected all over the place—these things betrayed her the instant she opened her mouth. . . .

If this is how Rezzori writes about a lover, we can imagine what he felt about the rest of Romanian Jewry. Romania was reputed to be the most anti-Semitic country on the continent, yet I feel certain that had he encountered me with Peppi on one of our walks—say, in 1940 when he was a discriminating young man of twenty-six—my German chatter would have aroused in him no such revulsion. Indeed, he might have smiled and stopped to chat with the articulate four-year-old; I had curly blond hair, and Shirley Temple was then all the rage.

Of course, nothing turned out as intended. Der mentsh trakht un got lakht. English makes the point smartly—man proposes, God disposes—but in Yiddish God laughs, mocking our best efforts to control our fate. Intended to ready me for a lifetime in Europe, my mastery of German would prove its true value during our escape from Europe. How extraordinary that what you prepare for—in our case, life in a thriving multilingual Romanian metropolis—should yield not a sensible return on a sensible investment but a means of prying you from that life. That is, if you are prepared to sacrifice the sensible investment. When I look for words to describe my parents’ readiness to leave instantaneously the comfortable lives they had built, I find its closest approximation in the Passover Haggadah’s tale of the Israelites’ flight from Egypt with the armies of Pharaoh in hot pursuit.

II

My father Leib Rojskiss, later Leo Roskies, was a short, slight man with dark tight curly hair and thick glasses who had come to Czernowitz in 1932 to build and run the first rubber factory in northern Romania. His life until that point could have been the stuff of a Fortune magazine profile:

In 1930 an impecunious recent graduate in chemical engineering from Stefan Batory University in Vilna was hired by WUDETA, a rubber factory in the Polish industrial city of Krosno. Fifteen-year-old Leo had left his traditional Jewish home in Bialystok to get a general education, and then went on to university. Intending to study agriculture with the aim of going to Palestine to cultivate the land, he turned to chemistry on learning that the university’s faculty of agriculture was closed to Jews. He married and started work the year he graduated.

WUDETA was named for its owners WUrtzel and Daar and for the city of TArnow where they had founded the business, producing rubber footwear and bicycle tires for domestic and foreign markets, including neighboring Romania. Typically, though the owners were Jews, the plant employed Jews only for management and distribution and never for production. Enoch, an older Rojskiss brother, was thus duly hired for sales. But an exception was made for the newly-graduated chemist Leo, who was hired for production and was expected to learn the formulas being used by the Swedish chemists whom the factory owners did not fully trust and wanted to replace. Leo succeeded at his assigned task and won promotion to chief engineer.

At about this time, Romania imposed restrictions on Polish imports with the aim of developing its own industry, and rather than accept this setback, WUDETA sent Leo to Czernowitz to establish a new factory there. Not yet thirty, Leo oversaw the development of CAUROM (CAUchook ROMania), which became a hugely successful manufacturer of rubber products ranging from rainwear to rubber balls. He adored the industry and set out to produce superior goods under the best possible factory conditions. Among his rewards was a medal from King Carol.

Other Jewish manufacturers in Czernowitz at the time produced baked goods, buttons, candies and chocolate, chemical products, dried milk and processed foods, furniture, hats and caps, hosiery, printed materials, soap and candles, soda water, and of course textiles. With his brother Enoch in the front office as sales manager, Leo worked hard, knowing that the king’s gratitude for their efforts was not shared by all Romanians. Hard nationalists called the Jews predators, while Marxists saw the rapacious capitalist behind every factory owner. Much as Leo appreciated his newfound prosperity—our parents became wealthier in Czernowitz than they would ever be again—he did not mistake his success for security.

Trying to account for Father’s wariness, greater than that of most of the Jews around him, I find a clue in an episode from his student days in Vilna. This little story always beguiled me. Like most of his cohort, Leibl, as he was known to his friends, had started out politically on the left, never formally a Communist but close enough that a Bialystok friend wanting to cross over to the Soviet Union asked Leibl for help. The process was known as shvartsn di grenets—“blacking the border,” i.e., getting smuggled across the frontier separating the newly reestablished Polish Republic from the newly founded Soviet Union.

Vilna Jews appreciated their relative freedom under Polish Prime Minister Jozef Pilsudski, but Poland’s formal democracy also allowed the formation of anti-Semitic nationalist parties. By contrast, the Soviet Union had officially outlawed anti-Semitism and promised international brotherhood. Young people were enchanted by the lure of the red-brick road. To help his friend Chaim reach his promised land, Leibl and a third friend raised the required 200 rubles and gave the smuggler half on account, the rest to be paid when he returned with the password given him by Chaim once safely deposited at his destination.

The plan was conceived in high spirits. The boys chose for their password the Hebrew-Yiddish word k’mat, meaning “almost,” but when spelled differently becoming an acronym for kush mir in tukhes, kiss my ass. How clever they must have felt when the smuggler returned the naughty password for the balance of the cash! But Chaim was never heard from again. This was the fate of many idealists whom the Soviets caught and convicted of spying—which did not dampen local enthusiasm for the great Soviet experiment.

But Leibl was taught his lesson. Chaim’s mother, a Bialystok neighbor of the family, blamed him for the disappearance of her son and threatened to denounce him to the police. Leibl’s father kept a wad of money in the house in case of his son’s arrest. Thereafter, Leibl stayed clear of Communists; when he moved to Czernowitz he knew that, should the Soviets ever invade Romania, his chances of survival as director of a factory would be at least as slim as they would be were Hitler to attack from the West. Stalin had unleashed the Great Terror in 1937, leaving no doubt about his murderous methods.

In 1939, one of Leo’s trusted employees (whom I know only by his family name Boncescu) left his job at CAUROM to take a government position near the northern border. Leo asked him to notify us immediately if the Russian troops ever approached or crossed into the country. By the day Boncescu called with the news, in early June 1940, Father was already in Bucharest trying to arrange our exit visas. Mother packed us up and within a few hours we were on the train to the capital.

Mother left behind two items that she had gotten ready and intended to take along in her hand luggage: a framed photograph of her father and a songbook by the Yiddish poet-songwriter Mordecai Gebirtig with an inscription thanking her, a good amateur performer, for how well she interpreted his songs. Whenever she recalled these items, she would add, “But I did not forget to take your potty and your white shoes,” which I understood to mean either that she was distracted by my needs or that she deliberately placed them ahead of her own.

Father never mentioned what he had left behind. Peppi accompanied us to the train, but no further. Were this a work of fiction I would try to make much of the moment of our departure, but I have no idea whether I dreaded leaving or felt pleased to be setting out on an adventure with my older brother. As I have no memory of it whatsoever, I can only record that we left Czernowitz on the same day in June 1940 that we received direct news of the Soviet invasion of Romania, and that I never saw Peppi again.

Why did we leave? Whenever I am identified by my place and date of birth, Czernowitz 1936, it is usually followed by some sentence like “Her family fled the Nazis and came to Canada.” I try to correct the mistake in the cause of truth and because the error is symptomatic of the understandable desire to simplify a complicated history. Though most of Mother’s family and a large part of Father’s were indeed murdered by the Germans, we actually fled the parallel and prior evil enshrined in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 that had divided Poland between the two parallel predators. Leo deduced that Stalin, having invaded Poland, would also invade Romania. By 1940 every Jew knew the hazards of Hitler, but my father did not yield to the subtle moral blackmail concealed in the claim of Communists that they were the only alternative to Hitler. He knew it was possible to have more than one enemy.

III

Mother’s role in our exodus was less daring than Father’s but no less consequential; had she resisted our departure, he would not have organized it. Her readiness to take flight was the more admirable since in following Leo she had already been twice uprooted.

The first time was just after their marriage, when she left her native Vilna and an adoring circle of friends for Krosno, a factory town with no Jewish society at all. That was in 1930. The birth of Benjamin the following year, however welcome, increased her isolation as a young mother. She knew nothing about infants and had no family or friends in Krosno to advise her, not even about the need to burp a baby as part of its feeding. Her memories of her two years there were traumatic, featuring illness (hers), indigestion (the infant’s), and factory intrigue around Leo.

Thus, she was much happier with their second relocation to Czernowitz, known in cosmopolitan circles as “Little Vienna” and in Jewish circles as “Jerusalem on the Prut” thanks to the conspicuous presence of some 42,000 Jews, more than one-third of the population, among them many other young professionals and their wives. Moreover, though German was considered the language of culture, the city also had a special connection to Yiddish, Mother’s favorite of the six languages she knew. She had developed a large repertoire of Yiddish songs that she sang a-cappella or while accompanying herself at the piano.

The multinational Austro-Hungarian empire had conferred on every minority “an inviolable right to the preservation and use of its own nationality and language,” allowing Jews to develop their culture in Hebrew and Yiddish, and had made Czernowitz the logical site of the 1908 founding International Conference on Yiddish. The city remained a Yiddish stronghold when it became part of the Kingdom of Romania in 1918. Masza Rojskiss attended performances of touring Yiddish actors and singers, some of whom she had gotten to know in Vilna, and though she never became a professional musician like two of her older half-sisters, she sometimes sang at the Zionist club Masada, which she and Leo joined and where they found their new friends. The inscribed songbook by Mordecai Gebirtig, praising her renditions of his songs—the book she forgot in the haste of departure—speaks to her success in bringing Yiddish into the Germanic-Hebraic culture of Czernowitz’s Jewish high society. Leo’s status and her liveliness won them an interesting and welcoming circle of friends.

There were servants, a chauffeur for Father, a housemaid in addition to Peppi, and money to help less prosperous family members back in Poland. Nonetheless, Mother, too, did not fully trust their prosperity, especially after Odele died. One of the songs she had learned from her older sister Anna Warshawska acknowledged this distrust: Zol es geyn, zol es geyn vi es geyt, vayl dos redl fun lebn zikh dreyt. Let things go as they must, because the wheel of fortune spins, today in my direction, tomorrow in yours. The song’s plaintive tones, so at odds with Masza’s temperament, seemed to foretell a reversal of fortune.

In later years Mother was sometimes angry, even unforgiving, of those trapped in Europe by the war whom she suspected of having let their possessions weaken their powers of self-preservation: “She wouldn’t leave her carpets!” Her annoyance may have masked guilt over having failed to rescue her beloved sister Annushka, murdered with her husband and family during the extermination of the Kovno ghetto. Anna was a singer on the radio, a woman of wealth, and by 1940 was eager to leave Poland, but unlike Masza’s husband, hers could not secure the necessary papers. Gratuitous guilt would cling not only to most survivors but to those like my parents who had made it to safety. Though I thought Mother’s astringent way of dealing with it terribly unfair, I preferred it to Father’s self-reproach.

In assessing the ratio of personal initiative to luck in our survival, I must include another detail that could almost certainly have prevented our departure from Czernowitz. A couple of years after I was born in 1936, Mother became pregnant again. She herself was one of ten children, and she wanted more than two. Her obstetrician was a member of the Masada circle. When she went to confirm her pregnancy, the doctor told her to ready herself for an abortion: he would end the pregnancy then and there. Masza, having expected a welcome affirmation of her condition, protested, but the doctor overrode her objections, insisting that 1938-9 was no time to be having a Jewish child.

I doubt that our parents would have undertaken so uncertain a journey or managed it as adroitly as they did if they’d had a new infant in tow. Owing our lives to this unborn child as we do, I cannot absolutely oppose abortion, though for the same reason I also believe in having more than just a replacement level of Jewish children.

IV

The person most directly responsible for our rescue from Europe was my paternal grandfather David, who had been blind for the last 40 of his 80 years. For the Passover seder of April 3, 1939 the entire Rojskiss family gathered at the patriarch’s home in Bialystok—all except our branch that stayed in Czernowitz because Ben and I had come down with scarlet fever. It was apparently at this gathering that zeyde instructed the family to buy a textile factory in Canada—textiles being the longstanding family business. He instructed the son and grandson whom he considered the sharpest businessmen to leave at once and arrange for others to follow as soon as they had concluded the deal.

One of my cousins believes that the two men had already been in Canada several months earlier to finalize the purchase of a woolen mill in Huntingdon, Quebec—but in either version, it was our grandfather’s vision that set this plan into motion. He must have learned about the depressed state of Canada’s textile industry and concluded that the government’s concern over the production of woolen goods might outweigh its aversion to Jews. Though the historians Irving Arbella and Harold Troper show Canada to have had the worst record in the civilized world for admitting Jews, in this case the country evidently put its economic interests first.

Thanks to Grandfather’s foresight, all four of his sons made it out of Europe, though one daughter-in-law and two granddaughters, stranded in Poland when war broke out, did not reach Canada until 1945. Doomed in Bialystok were Aunt Perele, the sister who stayed behind to care for our grandfather, with her husband and two children, and the blind visionary himself. The sons in Canada tried to get this part of the family out of Poland in time, but failed.

I thought of this ancestor whom I’d never met when I studied King Lear, a play about old men, one of them blind, who “stumbled when they saw” and developed insight only once they were humbled by the consequences of their poor judgment. I come from different stock. When my grandfather lost his sight, he arranged for a local yeshiva student to come to his home every day and help him study Talmud. I imagined this young student as the Earl of Kent and Grandfather as a regal personage of exceptional wisdom. His wit, however, was unkind and sometimes caustic, especially when it came to his sons’ romantic pursuits. He showed his concern for his children in other ways. What he saw in his blindness was the black heart of Europe.

Literature has not registered a man as perceptive as Grandfather, killed in the Bialystok ghetto.

V

Bureaucracy can be tyranny’s loyal enforcer. It was the lower-level officials who almost prevented us from escaping Europe and reaching Canada. Our parents had come to Romania as Polish citizens. When Germany expelled its Polish Jews in 1938, Poland, fearing their return, decreed that reapplying citizens needed to have their passports stamped anew. This almost completely blocked the repatriation of its expelled and undocumented Jews. The border city of Zbąszyń became a transit camp for Polish Jews who now could not travel in either direction. Effectively it was a ghetto, since, unlike in earlier centuries when Jews could always run somewhere else, the entire world was now sealed against their entry.

In any case, as Father knew, we would have been doomed had we traveled with Polish citizenship: independently of his father in Bialystok, he had already begun making contingency plans for our eventual departure from Europe. Thanks to his expertise in rubber production, he had secured visas for South America; but he was not enthusiastic about moving to a place where he had heard there were only rich and poor. He preferred the freer democracies of North America, and since his brothers were already in Canada, he probably wanted to be near them rather than solitary on a continent where he had no kin.

Disturbances were raging around Bucharest as Father tried to arrange our travel in June 1940. Thanks to the medal he had received from the king, the Romanian officials granted us exit permits. We therefore left Romania as stateless persons, heading for Athens by train. Father hoped that somewhere along the way he would receive entry permits to Canada, secured by the family members already there, and in Athens the precious documents reached us. By the time we boarded the ship at Piraeus, headed for Lisbon, we could say that Montreal was our final destination.

We were refugees masquerading as tourists. My white shoes that Mother remembered to take with us when we left Czernowitz figure in a group photo taken in front of the Parthenon, where we are all in stylish attire. Mother would later tell me that during our travels they took to calling me Fräulein Hoffentlich for the way I spiced my sentences with the word “hopefully.” They placed me in front when we came to checkpoints, confident that my confidence would render us passable.

As we traveled, the political situation grew worse. By the time we reached Lisbon in September, France had fallen, touching off what the historian Marion Kaplan calls a “stampede” of refugees to the city, many of them similarly in transit. We were among approximately 80,000 Jews who found temporary asylum in what centuries earlier had been the launching pad of the Portuguese Inquisition.

Anyone who reached Lisbon had already run the gauntlet of officialdom. In our case this included border guards at ports in Italy and Gibraltar, who reserved the right to sequester improperly documented persons. The Italians did not remove any passengers from the ship, but the British did, and though they spared us, it was the arbitrary cruelty of those officers impeding refugee flight that forever complicated our thinking about the British, already tainted by what we knew of their refusal to grant desperate Jews entry to Palestine.

The most threatening point of our journey was the least expected. It occurred at the American consulate in Lisbon. Father had secured us passage on the Nea Hellas, a Greek ship that was to depart Lisbon on October 4 and dock in New York nine days later. From there we were to travel to Montreal with our recently issued Canadian papers. But we needed transit visas for the period between landing in the United States and boarding the train to Montreal, and these the American consulate would not issue without medical tests that included an ophthalmologist’s assessment of Father, who wore thick glasses.

When Leo (as named in the visa) went to the appointed medical office, he was informed that the doctor was on vacation and would not return until after our ship’s scheduled departure. Back we all went for a referral to another doctor, but now the consul denied Father’s request and said he would have to wait for the authorized doctor’s return. Father exploded: “You are a crazy man! Our ship sails this week! Will you throw away the lives of these children? Give me the name of another doctor or I will kill you!”

I am going by Mother’s description of this outburst, which convinced her that we were now doomed. As I do not recall Father ever raising his voice to us, I like to imagine him shouting in his recently acquired English. His unlikely eruption had its effect, however. The consul said that I reminded him of his own daughter and issued us the visas. End of episode.

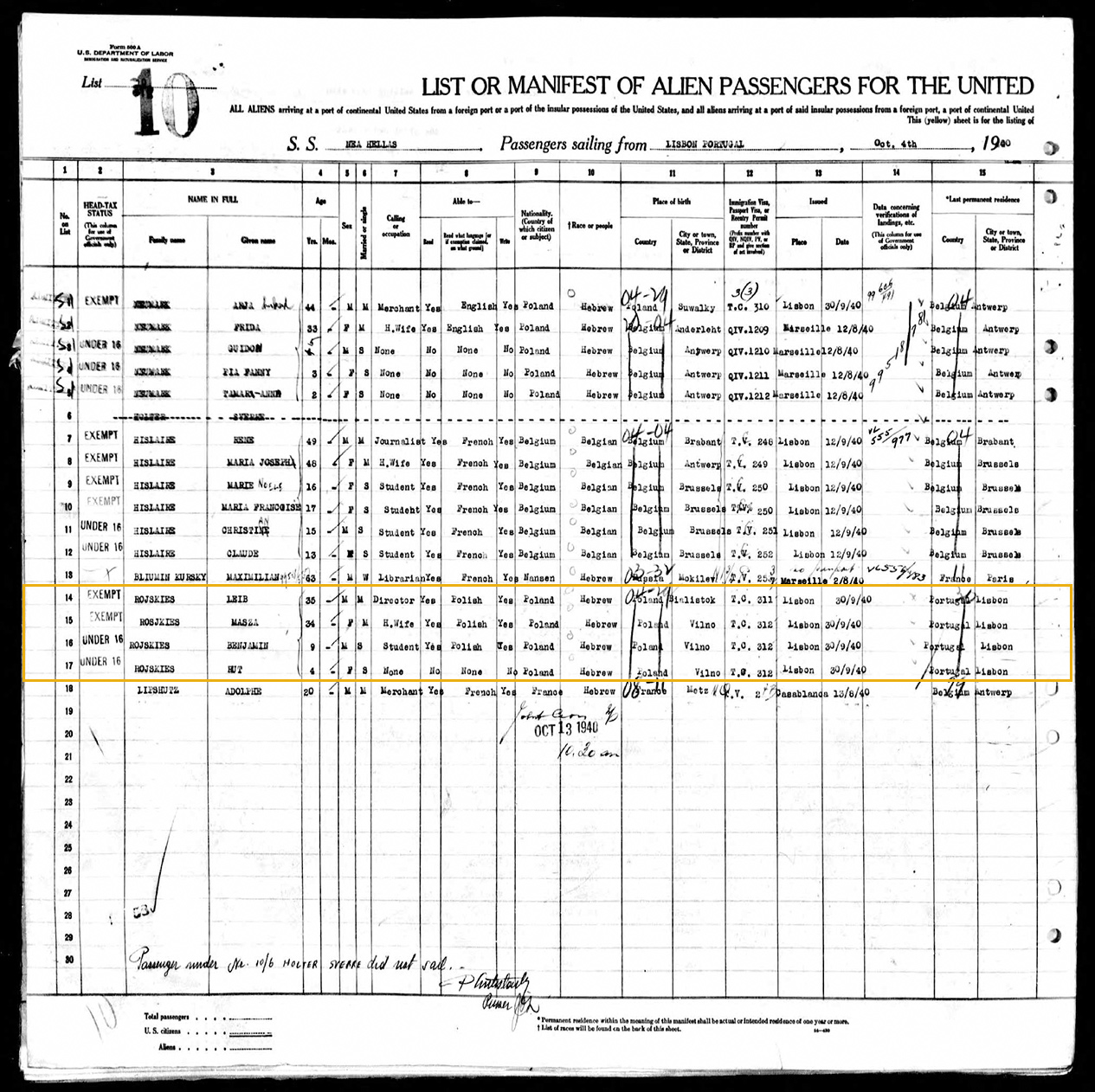

The manifest for the ship that the Roskies family took from Lisbon to New York in 1940. The family is outlined in yellow near the bottom. Courtesy Ruth R. Wisse.

Sometimes I have imagined this scene from Ben’s angle. While throughout our journey I was the featured adorable mascot, he was under strict orders never to say anything unless directly spoken to, and then never to reveal anything he knew. He spoke only Yiddish and Romanian and was just learning English. Had he tried to say something, he would have betrayed his alien status. Already a semi-adult at age nine, he listened to Hitler’s radio broadcasts and understood the menace in those lunatic ravings.

I would later learn from Ben about a point in our journey when our parents searched hysterically for documents they had misplaced. I can imagine the effect on him. Because I recall nothing of those months, I don’t think I ever lost the sense of security imbued in me since infancy by our lives in Czernowitz. If Ben had ever felt the same sense, it must have ended that day in the consular office when our father almost cost us the lives he was working so hard to save.

Father’s out-of-character outburst can serve as yet another warning against trying to match input to outcome. Families with the best laid plans were betrayed and doomed after successfully hiding for years; the bravest ghetto fighters fled through the sewers and emerged in open air only to be executed by tipped-off Stormtroopers; survivors returning to their native towns were axed and stoned by their former neighbors. By lucky contrast, Father’s uncalculated eruption parted the sea for us.

We set sail on the second day of Rosh Hashanah 1940 and arrived in Montreal via New York on October 19. In later years I read somewhere that the Nea Hellas was torpedoed on its return crossing, but from the Internet I’ve recently learned that in fact it was decommissioned for use as a British troop ship during the war and then returned to service.

All that I remember from that period in my life is a little green leather purse that Father bought me at an outdoor stand in Lisbon. It was square with a clasp at the top and a leather strap. I still had it in Montreal when we moved the first time, but then it disappeared and I long mourned its loss. Everyone has had dreams of the kind I dreamed about losing that purse. Maybe I had to lose it, as a stand-in for all the things I did not remember parting with.

Fortunately, Mother did take with her most of her photographs, so that I grew up with images of her brothers and sisters, friends in Vilna and Czernowitz, her courtship and marriage, our vacations in summer and winter, and so forth. Apart from the formal studio portraits, her brother Grisha was a talented amateur photographer and many of the snapshots are his. Our home in Montreal displayed pictures he had taken of me and Ben; but I never saw a picture of me with Peppi.

Coda

In 1985, Guy Descary, the mayor of Lachine—today a borough of Montreal—decided to name the new local library for Saul Bellow, the township’s most famous native son, whose name and birthplace he had discovered on a list of Nobel Prize laureates. With his eye on the next election, Descary thought he could parlay the dedication ceremonies into good publicity, and he drew the Montreal Jewish community into his plans. Norma Cummings, a local lover of the arts, arranged a party for the celebrant in her home and garden.

It was an enchanted evening. I sat for a while beside Saul’s then-wife Alexandra, of whom I knew only that she was a mathematician (no hope for conversation there) and a Romanian, a detail I had learned from reading Saul’s novel The Dean’s December, much of which is situated in Bucharest. I told Alexandra that she and I had something in common: I, too, was born in Romania. Had she by chance spent any time in Czernowitz?

Yes, as it happened, she knew the city well. It was the home of her parents’ very close friends, a Ukrainian doctor and his Jewish wife who was also a physician: an obstetrician. She thought of this woman, Rosa Zalojecki, as her godmother. During the war, the Christian husband had refused to divorce his wife and died in prison. But Rosa and her son survived and after the war they immigrated to Israel, where she kept up her medical practice into her eighties. Alexandra and Saul had recently visited her there. (I thought: this must have been the trip chronicled in Saul’s To Jerusalem and Back!) Alexandra asked whether my parents might have known the Zalojeckis.

From what I knew of our parents’ life in Czernowitz, I said it was unlikely. They had arrived from Poland only in 1932, and while the local Zionist circle included several doctors, I did not recall them mentioning that name. I told Alexandra that my parents had socialized mostly with other Jews, but that I would ask. The next morning, I put the question to Mother: had she known a Rosa Zalojecki in Czernowitz?

Mother said, “Of course. Rosa Samet.”

“Zalojecki,” I corrected. “She was an obstetrician and gynecologist.”

Mother then corrected me: Rosa was a Jewish girl from Poland. Zalojecki was her married name. She was married to a Ukrainian—also a doctor—but her maiden name was Samet. “Of course I knew her. She gave you your name. When you were born, you came out so suddenly that I began to hemorrhage, and the midwife was afraid for my life, so she called in Rosa Samet and told her it was an emergency. Rosa was known as the best obstetrician in the city. She came right over and stopped the bleeding.”

So much for the storied ease of my birth!

Mother went on with her tale. Because Rosa was afraid of complications, she stayed for several hours and during that time she asked what Mother intended to name me. Mother said “Tamara,” after a girl with lovely braids who had lived in their Vilna courtyard. (I was kept in braids for many years.) But the good doctor advised her against it, saying that she herself had suffered from being named Rosa and this was not a time to burden a Jewish child with a recognizably Jewish name. “She told me to call you Rut, a good Romanian name. I took her advice and told Father to register you as Rut.”

The Czernowitz registry that I cited early on confirms Mother’s account of my name—but without Alexandra, I would never have learned what lay behind it. Mother recounted all of this as though she had never imprinted in me the image of the bouquet tendered her by the landlord as she lay in her sunny bedroom attended by a cheerful midwife—my bed of roses. It could be that she saw no contradiction between hemorrhage and bouquet, but had simply given me the happier version.

I am clearly not qualified to question memory, having (as I’ve said) no memory of my German-speaking childhood. Ben, however, remembered Peppi, and in the 1960s looked her up on one of his business trips to Paris, where she had accompanied another family from Czernowitz and thus survived the war. He thought that Len and I should bring her over to be the nanny of our firstborn son, but nothing came of it.

It is curious but fitting that Saul Bellow should have figured in securing the facts of my birth. My copy of Herzog falls open at the scene where the hero, tortured by the knowledge that his wife has been cuckolding him with his closest friend, is looking for sympathy among the people he knows. He visits the lawyer Sandor Himmelstein, seeking help in fighting his wife over alimony and custody of their child in the ensuing divorce. Instead of helping his friend, Himmelstein is provoked by this show of weakness, and his cynicism goads Herzog into an angry counterattack:

“Do you know what a mass man is, Himmelstein?”

Sandor scowled. “How’s that?”

“A mass man. A man of the crowd. The soul of the mob. Cutting everybody down to size.”

“What soul of the mob? Don’t get hifalutin. I’m talking facts, not shit.”

“And you think a fact is what’s nasty.”

“Facts are nasty.”

“You think they’re true because they’re nasty.”

Himmelstein is annoyed by the naiveté of this grown man, and wants to teach him the score: a wife who has spectacularly betrayed her husband would certainly get the better of him in court. But Herzog will not tolerate the reduction of realism to excrement. Truth can be nasty, but the nastier version of the facts is not necessarily the truer.

So, too, with Mother’s revelation. Normally a staunch member of the Himmelstein camp of realists, she would insist that “life is a war,” that “kindheartedness to the cruel is cruelty to the kindhearted”: a rakhmen af gazlonim iz a gazlen af rakhmonim, in the Yiddish version of this talmudic aphorism. But if she remembered my birth as a gift of roses rather than a river of blood, so much the luckier for me. In the same hopeful spirit, maybe I could say that I helped her and Father a little during our exodus by taking her mind off what was happening in the rest of Europe, and after the war by taking their mind off what they had not managed to do for others.

Hopefully.

More about: East European Jewry, History & Ideas, Holocaust, new-registrations, Poland, Soviet Union, The Memoirs of Ruth Wisse