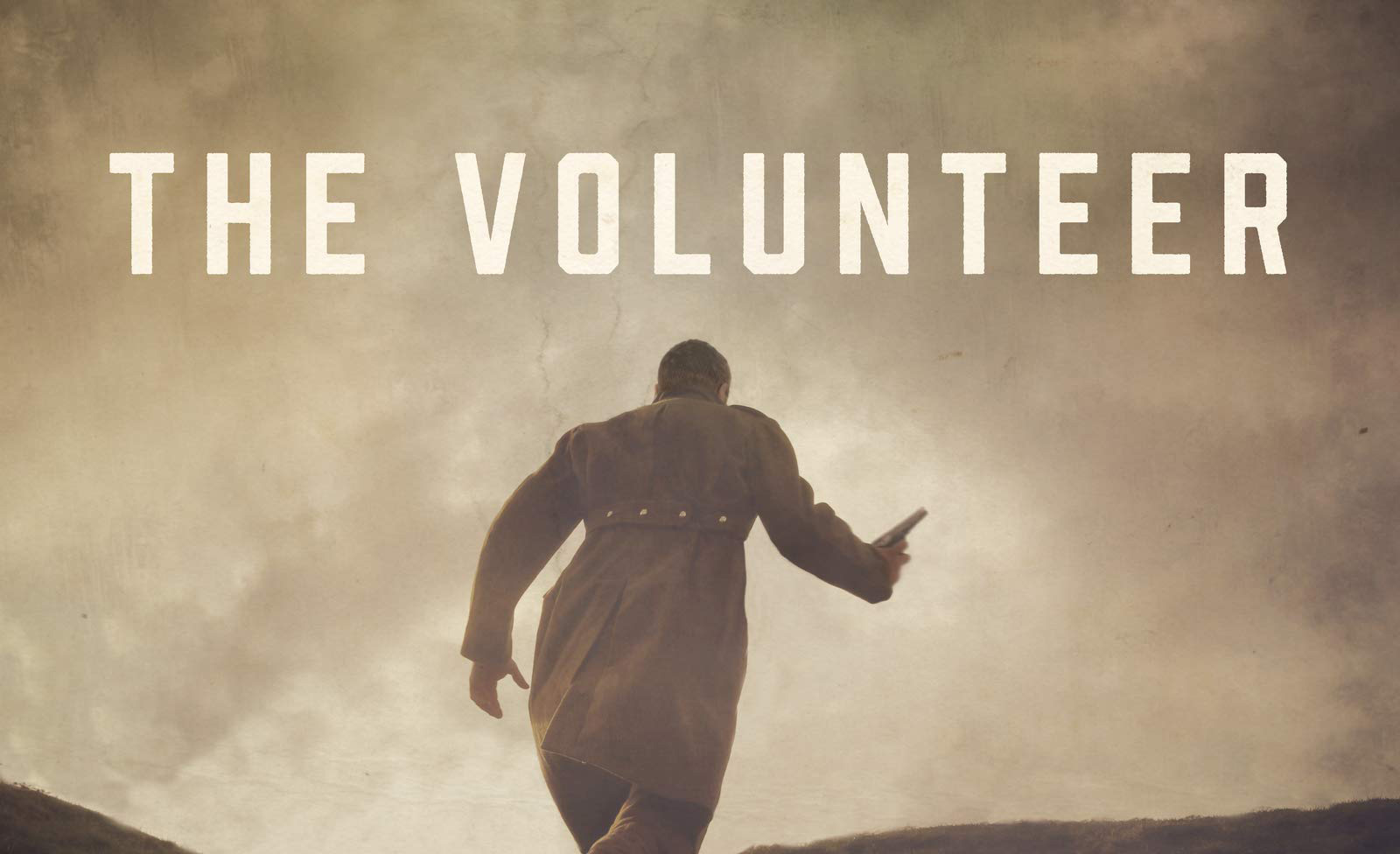

In 2008, PBS aired a documentary about Jewish prisoners who somehow managed to escape from Auschwitz. Some 144 people—out of many hundreds of thousands of inmates—are thought to have snuck out of the camp alive. But perhaps even more daring, and less well known, is the story of Witold Pilecki, a non-Jewish Pole who deliberately made his way into Auschwitz and remained there, despite opportunities to escape, in order to document the camp’s horrors. As detailed in The Volunteer, a recently published book by the British journalist Jack Fairweather, there was nothing in Pilecki’s early life to suggest such heroism.

Born in 1901 to a modest noble family in what is now Belarus (then Russian-ruled Poland), Pilecki was a mostly apolitical man “of his time and social class,” likely sharing that time and class’s casual anti-Semitism and condescension toward the local peasantry. After his father took ill, Pilecki took control of the crumbling family estate, married, and had children.

This contented and conventional life changed upon the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. At the time, Pilecki was serving as a second lieutenant in the Polish cavalry reserves. After a brief clash with the overwhelmingly superior Germans, he and his unit had no choice but to retreat. They were hardly alone: between them, the Nazis and Soviets, then bound together in a mutual non-aggression pact, succeeded in completely subduing the entire country within a few weeks.

Impelled by an uncomplicated patriotism, Pilecki decided to fight on in an underground cell of what would later become the Polish Home Army. Its commander, Stefan Rowecki, had received scant but disturbing reports of a concentration camp built by the Germans in the town of Oświęcim, known in German as Auschwitz. Rowecki wanted someone to infiltrate the camp to document Nazi crimes, potentially spark an uprising, and pressure Western powers to act. Pilecki was recommended for the mission. After brooding over whether to accept, he finally agreed to be arrested in an upcoming mass roundup about which he had been notified by a Polish informant.

Once in Auschwitz, Pilecki was so unnerved by the Nazis’ brutality that within a day he concluded that the idea of an uprising was “naïve.” The SS and the privileged prisoners known as Kapos killed and beat with impunity. On Christmas Eve 1940, he recorded, the SS as “a joke . . . stacked as presents under the tree the bodies of prisoners who had died that day in the [punishment block], mostly Jews.”

Incarcerated in Auschwitz until 1943, when he made a bold escape with two fellow prisoners, Pilecki was in a position to see the transformation of the camp from a particularly murderous and brutal prison into a death factory that would become a metonym for the Holocaust. During those years, he methodically established a network of informants in all parts of the camp who provided him with a complete view of its operations.

If a member of his network was slated to be released, or was planning to escape, Pilecki would drill into his memory all of the pertinent information to be passed on to underground headquarters in Warsaw, from where it would make its way to the Polish government-in-exile and the Western Allies in London. Other agents would steal incriminating German documents and hide them just outside the camp perimeter, to be picked up by Polish underground fighters. Pilecki was particularly insistent that news reach the Allies of the systematic gassing of Jews, hoping (in vain) that it would produce an attack on the camp.

After his own escape, Pilecki partook in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising in which approximately 150,000 Polish civilians were killed and nearly the entire city was deliberately destroyed by the Germans. With the postwar takeover of the country by the Communists, he joined an anti-Communist intelligence network, was eventually arrested, tortured and interrogated for months, and placed on a show trial. Denounced as a fascist and a traitor, he was executed by a shot in the back of the head.

The backdrop of The Volunteer is the German occupation of Poland: ground zero for Hitler’s plan to re-engineer the racial makeup of Europe. Brutal even by Nazi standards, the plan aimed at destroying Polish society down to the roots. Libraries, museums, universities, and other cultural institutions were to be looted and shuttered. To make room for German settlers, the Polish populace would be demographically decimated, with a majority deported or starved to death and the rest, save for a select few deemed eligible for “Germanization,” enslaved. Although Nazi planners were at first vague about what would become of the Jews, they had no place in this utopia.

To implement this policy, the Germans immediately set about deporting Jews and Poles en masse from western Poland and replacing them with ethnic Germans from other parts of Eastern Europe. The SS and the Wehrmacht murdered members of the Polish elite by the tens of thousands. In the years to come, millions of Poles would be deported to work in Germany, and nearly two million non-Jewish Poles would be killed, very few of them in combat; three million Polish Jews were murdered.

The camp at Auschwitz, built in 1940 among former Polish Army barracks at the confluence of the Vistula and Soła rivers, was to play a key role in this exercise in demographic engineering. Its original purpose was to serve as a detention center for Polish political prisoners, disproportionately intellectuals, there to break their spirits and ultimately those of the Polish nation. Many were expected to die, but no apparatus of mass murder had yet been built.

After Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, the SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered Soviet prisoners of war to work the agricultural areas in and around the camp. Those too weak were considered expendable. One night, hundreds of these “useless eaters” were gassed in the camp’s penal block, an experiment that taught the Nazis the usefulness of Zyklon B for killing large numbers of people. Thousands more were shot and buried in mass graves.

To house the POWs, Himmler ordered the construction of an enormous camp in a nearby village named Brzezinka (Birkenau in German). But after millions of prisoners starved to death on the eastern front, and the Wehrmacht’s advance into the Soviet Union stalled, the numbers of deportees slowed to a trickle. A new pool of labor was required: Himmler settled on the Jews.

By this point the Nazi program of genocide was in full swing, but most of the killing had been done by shooting—which proved inefficient and bad for German morale. In Birkenau, the SS proceeded to brick up two peasant cottages and convert them into gas chambers. Jews unable to work were gassed and buried in mass graves nearby. Eventually, this process was streamlined through the construction of the gas chamber/crematoria complexes that facilitated the quick dispatch of corpses.

In 1942-3, the grisly work of destroying Jews was carried out mostly in the death camps at Treblinka, Bełżec, and Sobibór. But thereafter Auschwitz-Birkenau came into its own as the abattoir to which Jews were shipped from all over Europe. Nearly a million were murdered there.

As Fairweather emphasizes, Pilecki was uniquely positioned to witness both directly and indirectly the ghastly metamorphosis of the camp, even though he did not comprehend its full enormity. (How could he have?) But he did do everything within his power to bring its horrors to the attention of both the Polish underground and the Western Allies.

Starved to the point of physical and emotional numbness, stricken at one point with typhus, he remained singularly determined to complete his mission, at times arranging to remain in the camp when he could have been transferred or released. Even as he frankly admitted that he had trouble empathizing with the Jews, he never ceased his frantic efforts to get word out about their slaughter: “the most important thing,” he told an agent about to escape, “is the mass killing of Jews.”

About this, as is well known, nothing would be done. A thread weaving through the book is the Allied refusal to act in any way beyond the rhetorical to come to the aid of the Jews. Pilecki’s reports were read, but ultimately ignored. To emphasize Jewish suffering, the British and American governments believed, would spark anti-Semitism in their countries and give credibility to Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda that the Allies were fighting for the Jews; it was best to concentrate on defeating the Germans on the battlefield.

Not until two Jewish inmates escaped Birkenau in April 1944 and reported on the mass deportations and gassings did the scope of the horror really hit the Allies. As Fairweather shows, the groundwork for the Allied acceptance of these first-person reports had been laid by the extensive documentation provided by Pilecki and his network.

Winston Churchill, in a fit of fury and disgust, did call for Auschwitz to be bombed, but ultimately the British and American governments—for arguably practical military reasons, and for obstinate political ones—decided otherwise. Even the Polish underground told Pilecki that the camp had become relatively unimportant, superseded by revelations of the 1940 Soviet massacre of Polish officers at Katyń and the underground’s plans for a revolt against the retreating Germans.

Pilecki’s mission was thus ultimately a failure, and he knew it. What he saw in Auschwitz had shaken his faith in humanity: “We have strayed,” he wrote. “I would say that we have become animals, . . . but we are a whole level of hell worse than animals.” After escaping, he would write that he and his companions had been able to glory anew in the beauty of nature but their enthusiasm was dampened by their cynicism: “We were enchanted by everything. We were in love with the world, . . . just not its people.” Pilecki’s subsequent experience under Communism could hardly have tempered his disillusionment.

The Volunteer is a brisk read, at times feeling more like a spy thriller than a work of non-fiction, let alone one so impressively, intensively, and diligently researched. Fairweather’s habit of referring to his subject as “Witold,” grating at first, eventually succeeds in establishing a sense of intimacy with his protagonist, an otherwise obscure figure from a country at the far fringe of Western consciousness. Adding to the personalizing effect are Fairweather’s extensive quotations from primary sources, mostly Pilecki’s own notes or those of his fellow prisoners.

Given that the destruction of the European Jews is one of the most widely written-about events in history, why are Pilecki’s heroic attempts to inform the world about the slaughter at Auschwitz virtually unknown? There are two reasons: first, the postwar efforts by the Polish Communist regime to suppress his story along with much else about World War II; second, the inaccessibility of the Polish language to all but a relatively few Westerners. Fairweather has thus performed a great service, not only by making Pilecki’s own story, and in general that of the Polish resistance, more broadly known to the English-speaking world, but also by placing it in the context of the evolution of Nazi policy—a process that saw, among other things, the transformation of Auschwitz from concentration camp to death camp.

Fairweather tells us that his goal has been to write not only a “provocative new chapter in the history of the mass murder of the Jews” but also “an account of why someone might risk everything to help his fellow man.” This, however, is no easy task.

Pilecki does not seem to have been driven by politics or ideology. As opposed to the exclusivist notion of a Polish nation defined strictly by the Catholic faith and the Polish language, he had a more tolerant conception of Poland as an inclusive country that should encompass Jews and other minorities. Of course, in this view, Jews could never be “real” Poles, but they were nonetheless an essential and benign part of Poland. In short, his motivation appears to have been a remarkably selfless, old-fashioned love of country: patriotism combined with a basic sense of human decency.

One can’t help wishing Fairweather had pressed harder here. What were the sources of a patriotism strong enough to drive Pilecki voluntarily to infiltrate Auschwitz and to remain there, knowing he might never see his wife or children again? What had his family life been like? Did religion play any role? In the end, calling him a patriot and leaving it at that does not satisfy.

Yet Pilecki himself was neither a statesman nor a philosopher. An average man, quiet and to the point, a doer and not a talker, he devoted himself to the task of capturing the operations of Auschwitz, not the inner workings of his own soul. Above all, his own private prejudices be damned, he recognized evil for what it was and did everything he could to bring it to the world’s attention. That in itself is the key takeaway from his extraordinary life, and from Fairweather’s excellent book.

More about: Auschwitz, History & Ideas, Holocaust, Poland, Witold Pilecki