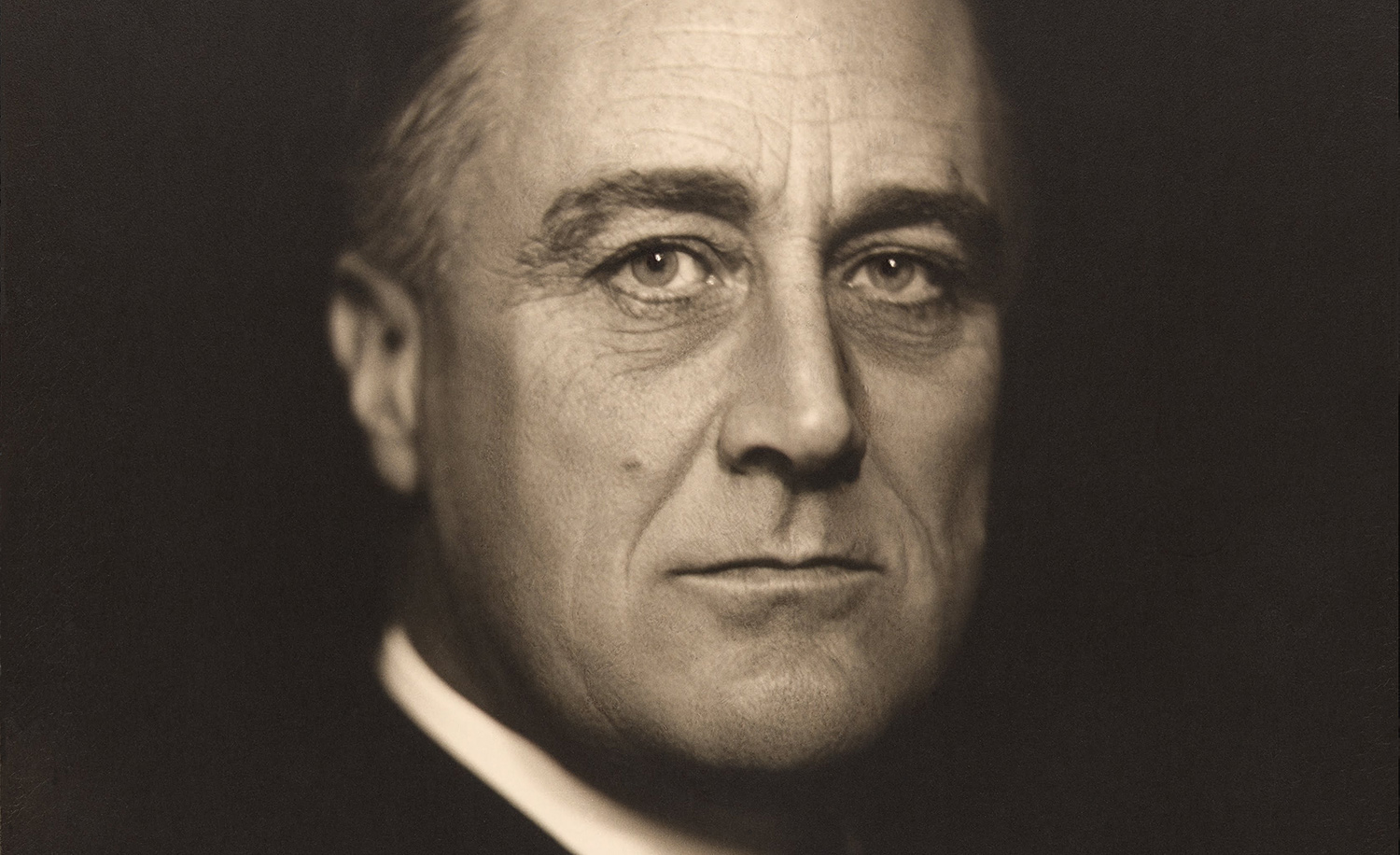

Franklin D. Roosevelt around 1932, taken by Vincenzo Laviosa. Wikipedia.

In writing about so fraught a topic as America’s failure to help the Jews during World War II, it’s well to begin by dispensing with the obvious: the Holocaust was a crime orchestrated by the Germans. Their leaders were propelled by a hate-filled ideology born of the humiliating aftermath of their defeat in World War I, a defeat they could fathom only as the byproduct of Jewish machination, cloaked in the twin (if also opposing) guises of Bolshevism and capitalism. As for ordinary citizens, German and otherwise, they were complicit in Nazi crimes; although the extent of their complicity still remains disputed, it is certain that the systematic persecution and extermination of Europe’s Jews could not have happened without the assistance and indifference of the populations of all countries under Nazi control.

Nor is the complicity of Europeans the only remaining controversy. Why did the Allies fail, or refuse, to save the Jews of Europe? Was it simple, bald indifference to the fate of the Jewish people? Or, given Nazi domination of the European continent and the overriding need to defeat Germany on the battlefield, did operational constraints thwart the possibility of any mission to protect or rescue the Jews? Or was it a combination of these and still other factors that left the Jews, hunted to the ends of the European continent, with nowhere to turn in their agony?

In The Jews Should Keep Quiet: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and the Holocaust, the historian Rafael Medoff, who directs the David Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, wades into these questions with compelling evidence about one of those “other factors”—and an eye-opening one at that. No stranger to historiographical combat, Medoff is previously the author of The Deafening Silence: American Jewish Leaders and the Holocaust (1987) and FDR and the Holocaust: A Breach of Faith (2013), as well as numerous articles, postings, and comments refuting what he identifies as the errors of others.

In his new book, an extension of the earlier volumes, Medoff charges flatly that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was an anti-Semite; that Rabbi Stephen Wise, America’s most politically connected Jewish figure, was the president’s obsequious sycophant; and that the Allies knowingly allowed the slaughter of European Jewry because they simply didn’t care.

To understand how Medoff reaches this conclusion, it helps to recall the post-World War I political atmosphere in the United States. Having fought in the fields and forests of northern France, Americans figured they had done their part for global order and retrenched into an isolationist mood. The Senate would not ratify American participation in the League of Nations, conceived by President Woodrow Wilson in order to “end war.” Congress passed acts capping immigration at minuscule levels, and zealous officials found ways to approve even fewer applicants than were allowed by the stringent quotas. Only once before World War II did Washington fill its annual quota for Germany, and that was in 1939, when the Nazis were still allowing Jews to leave, not yet actively bent on annihilating them.

It’s not as if no one knew about Jewish efforts to leave. In 1938, FDR himself convened a global conference in Evian, France to discuss what to do with the many Jewish refugees created by Nazi policy. The attendees made it perfectly clear that they were not wanted anywhere, except for the Dominican Republic, which offered to take in 100,000; a resolution by the nearby U.S. Virgin Islands to open its own borders was nixed by the State Department. By demonstrating that the Jews were everywhere unwanted, the conference played perfectly into Hitler’s hands.

Later that same year, after the murderous Kristallnacht pogrom, Roosevelt showed no interest in allowing 20,000 German Jewish children into the U.S.—in stark contrast to his rush a couple of years later, when the Germans bombed Britain, to open America’s doors to thousands of British children. Meanwhile, in 1939, the British themselves severely curtailed Jewish emigration to mandate Palestine, a major destination for Jews fleeing Germany.

In 1943, another international conference on the problem of Jewish refugees was held in Bermuda, to similar effect: the Allies would not agree even to providing transport and food—the bare minimum—for Jews lucky enough to have escaped the Nazis’ grasp. Thus, more than once, the nations of the West had consciously chosen to prevent the Jews from escaping the butchers pursuing them.

Throughout this period, American Jewry, though it made its voice heard, was unable to influence American policy. When it comes to Rabbi Stephen Wise, the unofficial leader of the community, the portrait painted by Medoff reveals two disabling sides of his personality. A cautious diplomat, he was convinced that his close relationship with the president would result in America’s making the rescue of European Jews an official war aim. At the same time, he was a jealous political operator who resented others whom he sensed encroaching on his place in the political establishment.

In this latter capacity, Wise looked down not only on grassroots appeals but also on political activism. He was disgusted by the members of the so-called Bergson group (named for its leader Peter Bergson), who protested in the streets, held rallies, and took out advertisements in major newspapers to excoriate the Nazi treatment of European Jews. Their loud clamoring, he argued, would not induce Americans to confront anti-Semitism; to the contrary, it would provoke anti-Semitism.

In Medoff’s devastating judgment, if Wise was altogether too much in awe of Franklin Roosevelt, too eager not to be a nuisance, for his own part the canny president took advantage of the rabbi’s affection, stringing him along with a series of empty promises, each one taken at face value and believed. Throughout his presidency, moreover, Roosevelt also explicitly told Wise and other Jewish leaders to keep quiet; hence the title of Medoff’s book. In a damning recitation, he writes:

[In 1936, the presidential adviser and future Supreme Court justice] Felix Frankfurter, conveying the president’s sentiments, had warned Wise “not to make any outcry” against the British Royal Commission investigating Palestine. Also in 1936 FDR had spoken directly to Wise about “the necessity for a time of Jews lying low [in the face of rising anti-Semitism].” In 1938 Roosevelt pressed Wise to neuter [a] planned American Jewish plebiscite [to fight anti-Semitism].

And so on. Even Eleanor Roosevelt, after Kristallnacht, lectured the Jews to lie low: “I think it is important in this country that the Jews as Jews remain unaggressive and stress the fact they are Americans first and above everything else.”

Wise heeded these admonitions. One might protest that in doing so he was operating no differently from many other well-placed Jews in Diaspora history who sought to secure Jewish communal interests by appeasing rather than confronting power. Not that he was indifferent to Jewish suffering or wholly passive; he discreetly pushed and prodded officials who were in a position to do something, and he issued public statements against Nazi atrocities. But, in Medoff’s telling, his fear of pushing too hard lest he antagonize the president and the administration led him into such cringe-worthy actions as putting the blame on Britain for the failed Evian and Bermuda conferences.

Medoff’s criticism of Wise rings true. Recognizing but reluctant to acknowledge the true dimensions of the threat, he took shelter in the ordinary, time-tested tactics for dealing with Diaspora governments. But America was no ordinary Diaspora, and the Nazis no ordinary threat.

The mass murder of the Jews of Europe began in the summer of 1941, when German forces invaded the Soviet Union and Nazi death squads, bolstered by auxiliaries from the native population, drove Jews from their homes and shot them by the thousands. Only infrequently did news of these massacres filter out to the West, obscuring the scale of the Nazis’ overarching intentions. In 1942, there were vague rumblings of “gassing in the hamlet of Chelmno,” but, cautioned by the experience of World War I, when several stories of atrocities committed by the German army in Belgium and France turned out to have been fabricated, many intelligence officials remained skeptical.

In August 1942, Gerhard Riegner, the representative of the World Jewish Congress in Geneva, was informed by a German industrialist with close ties to the Nazi leadership that it was now official Nazi policy to eliminate the Jews. (The Wannsee Conference planning the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” had been held in January of that year.) Riegner sent a report to the State Department, where it was promptly bottlenecked, and to the British, from where it made its way to Rabbi Wise. The State Department urged Wise not to speak publicly until the information could be verified. As soon as that happened, Wise held a press conference announcing the Nazi plan to annihilate the Jews, and the following month the Allies issued a joint declaration condemning this “bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination.” By then it was late November.

As Medoff relates, the State Department did not just delay the release of reliable intelligence. Its officials actively requested that American diplomats stop sending information about these crimes to Washington. A key figure in the campaign was Assistant Secretary Breckinridge Long, a nativist and anti-Semite who in a 1940 memorandum had explicitly stated his intention to do everything possible to prevent Jewish immigration to the United States. Even now, in possession of the facts, he remained committed to his goal of American inaction.

Long was opposed by Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, for whom the State Department’s obstructionism meant that the American government was in the position of “aiding and abetting Hitler.” When Morgenthau confronted the president about Long, FDR defended the man, who had been his good friend for decades.

The president’s defense of Long gets to the heart of Medoff’s assessment of FDR himself. In brief: he positively disliked Jews, whether the American Jews who had supported him or the European Jews whom he was content to let die by the millions. Adducing further pieces of circumstantial evidence, Medoff records an instance in the 1930s when the president expressed sympathy with the Nazis’ discriminatory treatment of the Jews, explaining how there were

specific and understandable complaints which the Germans bore toward the Jews in Germany, namely, that while they represented a small part of the population, over 50 percent of lawyers, doctors, schoolteachers, college professors, etc. in Germany were Jews.

As Medoff writes, the president also enjoyed telling “mildly anti-Semitic stories in the White House”; told Wise in a 1938 conversation that Polish anti-Semitism was the result of Jewish dominance of the Polish economy; once stated to an adviser that “Catholics and Jews are here [in the U.S.] on sufferance”; and objected to the presence of “too many” Jews in federal offices in the state of Oregon.

The president’s anti-Semitism seemed partly based on the same racial science appealed to by the Nazis themselves. For instance, Medoff links Roosevelt’s dislike of the Jews with his dislike of the Japanese: both groups lacked “blood of the right sort” and needed to be spread throughout the country in order to prevent them from exercising a disproportionate influence in any one place. Regarding the internment of Japanese-Americans, Roosevelt stated that, after their incarceration, they should be “scattered around . . . [so as not to] discombobulate the existing population”; he used similar language regarding the settlement of Jewish refugees, citing examples of counties in New York State and Georgia where, he thought, no more than four or five Jewish families per county was advisable.

In 1944, years after the Nazi killing was known to all, the president did sign an executive order forming the War Refugee Board (WRB), an interdepartmental organization charged with rescuing innocents in Nazi-occupied Europe. But he did so under duress: legislation to create a similar body was already pending in Congress, and it was politically expedient to pre-empt it. Although the WRB saved approximately 200,000 Jews and 20,000 non-Jews, its formation did not owe to any initiative on the part of Franklin Roosevelt; quite the contrary.

The single most damning—and still controversial—piece of evidence regarding the administration’s wartime attitude toward the Jews of Europe was its refusal to bomb the Nazi concentration camps. In April 1944, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler escaped Auschwitz-Birkenau and made their way to Slovakia. Their report about the camp, in which they detailed its layout and operations, made its way through Jewish organizations to the Allies. Vrba and Wetzler recommended that the camp be bombed. It was not.

The reasons remain fiercely debated (and it is also not clear that the question ever reached Roosevelt’s desk). Medoff, who believes that the Allies should have bombed the camp, lists the main rationales for not doing so. A bombing raid, let alone multiple raids, would divert resources from the overall war effort and, given the inaccuracy of aerial bombing at the time, could not be guaranteed to succeed. Bombing the railways and bridges leading to the camp, as many urged specifically, would be all but useless, as the routes could be repaired almost immediately. Bombing the camp itself would put the prisoners’ lives at serious risk. In sum, as awful as were the reports, the only way to put an effective stop to the Nazis’ crimes was to defeat the Wehrmacht on the battlefield.

Medoff then counters vigorously that the Allies did divert resources from the war effort in order to aid the Polish insurgents who in 1944 rose up against the Nazis in Warsaw. Moreover, they did so in full knowledge that the Poles had no chance of prevailing, and that the arms and supplies would be of symbolic value only. (They wound up mostly in German hands.) If the Poles could be aided despite being in a hopeless situation, why not the Jews?

That question is especially pointed in light of the fact that the Americans and British were even then bombing industrial plants throughout Upper Silesia, the region in which Auschwitz is located—including in Katowice, a city some 20 miles from Auschwitz, and in Monowice, part of the Auschwitz complex itself and a mere five miles east of the gas chambers. By 1944, when these campaigns were authorized, the western Allies had already captured strategic air bases in Italy from which bombers could reach the site. The German Luftwaffe was by then a spent force, and the Allies had complete control of the skies. A campaign to bomb Auschwitz still might not succeed, but by now it no longer carried heavy operational costs.

This leads Medoff to conclude that the refusal to bomb was a real choice, reflecting the Allies’ conscious decision not to prioritize rescue of the Jews.

Defenders of FDR have repeatedly brought up the fact that his cabinet contained more prominent Jews, among them Henry Morgenthau himself, than had any previous administration’s: a datum that should give the lie to any idea that the president harbored anti-Semitic attitudes. In light of the many statements cited by Medoff, and the president’s conscious, deliberate inaction to protect Jews during the war, that argument appears weaker than ever.

The Jews Should Keep Quiet is an unsparing and damning polemic against Roosevelt, and also against America’s most politically connected Jewish leader at the very moment when history most required his courage. But if Medoff’s book is significant for its corrections of the historical record, one comes away from it wondering whether, in the end, any of this mattered. Suppose Roosevelt had not been an anti-Semite; suppose a more insistent Wise had succeeded in moving him to resolute and swift action. How different would have been the fate of the Jews of Europe?

For one thing, who is to say that the State Department, or the War Department, on grounds either rational or disreputable or both, would not have succeeded in stymieing the president’s efforts? For another thing, what exactly could a more galvanized and determinedly activist American Jewish community have done to help their kin in Nazi-occupied Europe, who were thousands of miles away and caught in a whirlwind of unprecedented scope? Even had the administration prioritized rescue of the Jews among its other war aims, could it ever have matched the Nazi obsession with killing them?

In a world before the reestablishment of a sovereign Jewish state with a Jewish army capable of defending Jews anywhere in the world, the European Jews were utterly powerless, abandoned, and alone. The awful, heartrending truth is that, in the end, the only other people who cared about their existence, and with single-minded ferocity, were the relentless murderers empowered with the means to destroy them.