Recently, the American University of Beirut (AUB) made headlines when it was discovered, unsurprisingly, that the school does not list Israel as a nationality on the signup page for its online courses—meaning, effectively, that it bars Israelis. As AUB’s charter and accreditation is with the State of New York, the omission could render the school in violation of state or federal anti-discrimination statutes.

Why “unsurprisingly”? Because, for anyone with even a cursory knowledge of the institution and its reputation, this exclusion of Israeli citizens seems hardly worth noting. Throughout the prolonged turmoil of interethnic conflict in Lebanon until today, and despite the school’s professed devotion to serving as a neutral institution of higher learning, AUB remains a haven for supporters of Palestinian terror. Not for nothing did it earn the moniker “Guerrilla U,” bestowed on it by Newsweek back in 1970. Today, AUB mirrors the rest of Lebanon: divided along sectarian lines, united as a hub of anti-Israel activity.

Which makes it all the more curious that this same university, founded in 1866, was once home to a thriving community of hundreds of Jewish students. At its height in the early 20th century, Jews made up 12 percent of the student population—no small feat in an era when Jews faced restrictive quotas at major universities in America and Europe.

In those days, AUB’s Jewish students made up a vibrant and diverse community, drawn variously from recent Ashkenazi immigrants to the yishuv in Palestine, Iraqi Jews, the mixed Jewish community of Beirut itself, and elsewhere. And Jewish life at AUB was comfortable. Thanks to the availability of kosher food, the proximity to Palestine, and such extras as Hebrew-language instruction courtesy of the campus Jewish club, students were able to maintain their specific identity while benefiting from an excellent liberal-arts education. Jewish graduates of AUB would go on to hold prominent positions in public life, including eventually in the state of Israel.

What kind of school was AUB, and how did it come about? Its origins, in fact, lay outside of the Levant: in the United States, and in the dreams of a Christian missionary.

In 1855, the young Daniel Bliss sailed from Boston to the Ottoman province of Syria. As a student at Amherst College, he had been inspired by the religious dynamism of antebellum America. The Second Great Awakening was bringing thousands of “witnesses” to evangelical meetings centered on the theme of humanitarian service. One sermon in particular, by the Congregationalist minister Samuel Hopkins, struck the young man with its emphasis on Christian love as the cure for “poverty, injustice, and oppression.” To him, this was God’s mission not just for America but for the whole world—and he would be its agent. In his Amherst commencement address in 1852, he foresaw “no finality this side of the gates of the New Jerusalem” until liberty broke out “like day” across the world.

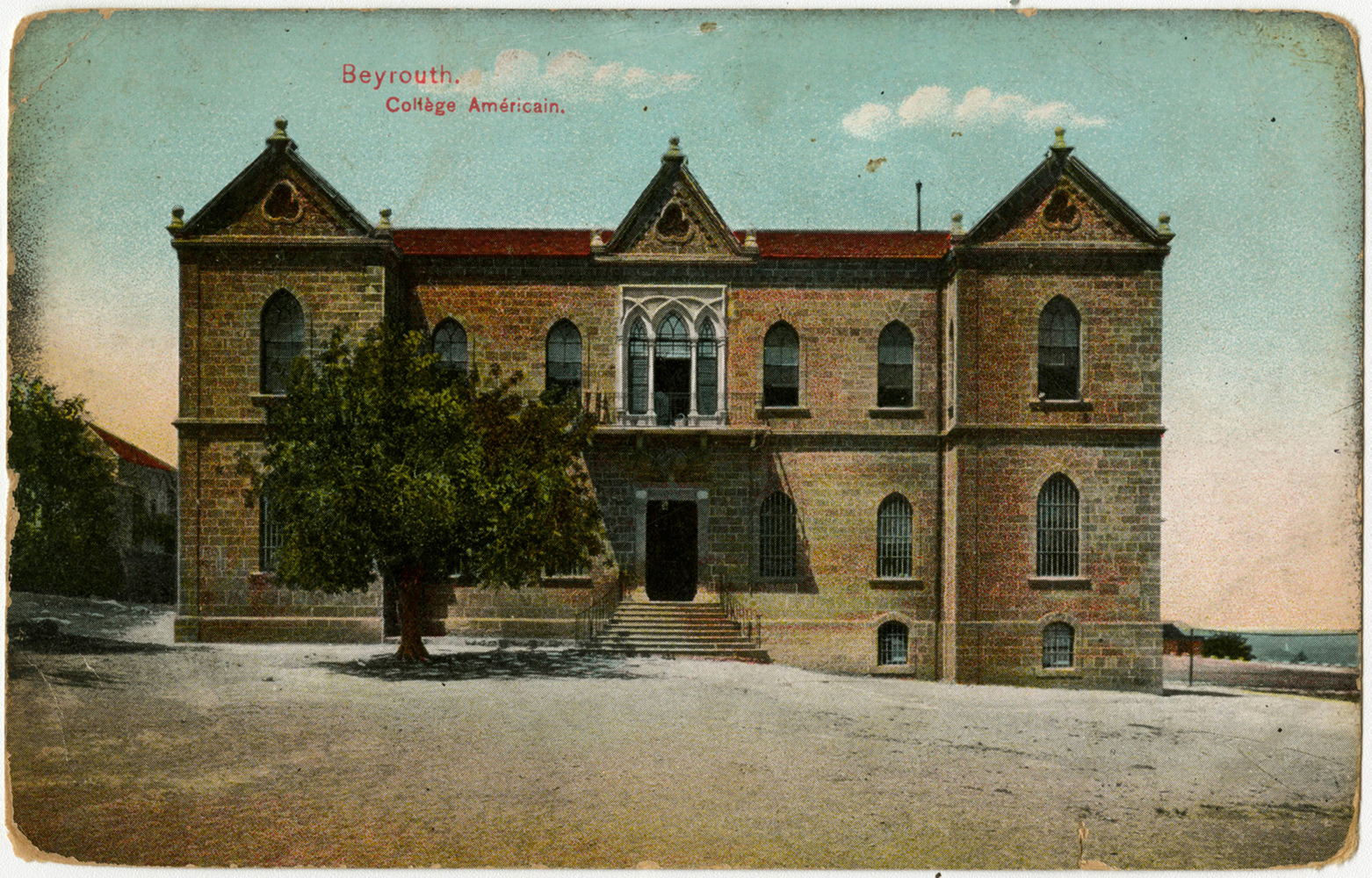

Relishing the particular opportunities to be found in education, Bliss aimed to bring out “the spirit of Christ” by founding an institution of higher learning in the “heathen, Mohammedan, and nominal Christian lands” of the Ottoman empire. AUB opened its doors in December 1866 as the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut (Lebanon then being an adjunct of Ottoman Syria but Beirut a stronghold of Maronite Christians). Housed in a four-room rented building, it had sixteen students and six instructors.

From the school’s inception, and as its first president, Bliss defined its educational methodology as a departure from the old-fashioned ways of rote memorization that offered little opportunity for critical thinking. His school would instead “foster a love of divine truth, whether revealed in nature or in God’s word.” At the same time, it would consciously be a Christian institution, aiming to create “perfect men, ideal men, godlike men after the model of Jesus Christ.”

The curriculum was ordered accordingly. In the arts and sciences it included English, French, ancient and modern history, philosophy, rhetoric, physics, mineralogy, chemistry, astronomy, geology, and physiology. In religion, even as Bible classes and attendance at services were compulsory, Bliss denounced blind adherence to faith and emphasized the role of human reason. In later reflections, he said that in classes on the Bible, no attempt was made “to combat error or false views”; instead, he “followed the method by which darkness is expelled from the room by turning on the light.”

As the 19th century progressed, the school’s growing reputation attracted applicants from across the religious spectrum; by the turn of the century, the Syrian Protestant College was making great efforts to accommodate both Muslims and Jews. The latter were excused from class on the Sabbath if their parents sent a formal request, and a kosher cafeteria opened on campus. The grand rabbi of Baghdad was reportedly so impressed that he decided to send his own son to the school.

But Bliss could not long preserve the uneasy balance between liberal education and Christian doctrine. In the roiling debate over creation versus evolution, which in the United States would entrench divisions between modernists and fundamentalists for years to come, he took a firm stance, ending the tenure of one professor who at a commencement ceremony eulogized the teachings of Darwin. Though Darwinian ideas had appeared previously in the pages of the school’s newspaper, airing in them in so solemn and prestigious a forum, in the presence of students, teachers, alumni, and parents, was deemed an unforgivable slight.

That was in 1882. By the turn of the century, student protests broke out, inspired by progressive ideals of religious freedom that proved difficult to suppress. In 1908 a visiting reverend from Tripoli, sermonizing on the New Testament text “Put ye on the whole armor of God,” referred to Muslims and others as “great walls of enemies.” “It is our business,” he proclaimed, “our sacred duty, to break down these walls and tread upon them.” In response, 75 Jewish students joined their Muslim peers in a strike.

Refusing to attend chapel or Bible classes, the strikers sent protesting telegrams to the American ambassador in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, the minister of the interior, and the sultan. They also called on the Young Turks, the heterodox anti-Ottoman movement then gathering strength in the region, to help bar the college from imposing religious requirements.

Howard Bliss, who had taken over from his father Daniel in 1902, assumed a conciliatory approach to the public outcry. “The first task,” he said, “is the task of putting ourselves in the place of our non-Christian students, our Muslims, our Tartars, our Jews, our Druse, our Baha’i.” At an institution founded to promote Christian piety, Jewish and Muslim students were now granted exemptions from chapel services for the remainder of the semester.

That same year of 1908 saw the founding of Kadima, the Jewish club on campus. Proudly Zionist, Kadima sought explicitly to “strengthen the national feelings of the Jews of the college.” Toward that end, it focused on “making Hebrew the everyday language of each of its members while he is a student.” Meeting every two weeks, members learned about Zionist thinkers and philosophy, organized excursions with the Jewish community of Beirut, and in 1914 threw a lavish reception for Henry Morgenthau, the new American ambassador to the Ottoman empire.

In 1924, Kadima inaugurated a pocket-watch fob to be worn “by all Kadima men.” The design, created by the Bezalel School of Art in Jerusalem, depicted a cedar tree—a symbol of Lebanon—within a large star of David. The fob was meant to emblemize the status the Jews had attained at AUB, where they felt at ease displaying both their Jewish identity and their affinity with their host country.

In fact, the writing was already on the wall. In the aftermath of World War I and the defeat of the Ottoman empire, seismic change rocked the region. With a League of Nations mandate over Syria and Lebanon now given to France, Beirut became “the Paris of the Orient,” the foreign population swelled, and a cultural tide of modernization affected every institution in the city. For its part, the university—renamed in 1920 and ever a place of intellectual activism and rapid change—morphed into a center of opposition to French rule. Inevitably, this was accompanied by a sharpened interest in Arab identity and, no less inevitably, by hostility to Zionism.

“Awake, O Arabs, and arise!” This 1868 slogan, coined by the Maronite journalist Ibrahim al-Yaziji, would become an impassioned rallying cry for later Arab nationalists. In the 1930s, Arab students at AUB heeded the call. From its first published issue in 1936, the school newspaper al-Urwa al-Wuthqa (“The Strongest Bond,” a phrase from the Quran and the name of a pioneering anti-colonialist Arabic journal) spoke collectively for every Arab student—the vanguard of the umma, the Muslim collective, “in its toilsome path toward the future.” In 1938, the Lebanese-Egyptian historian George Antonius published The Arab Awakening—the “preferred textbook,” as Martin Kramer has described it, of modern Arab nationalism, and one that exercised a profound influence in Lebanon.

By then the Christian identity of AUB had already begun to wane, ironically abetted by the progressive approach to public issues being promoted by the social-gospel movement in the United States. In his public speeches, President Bayard Dodge had conspicuously begun omitting references to the divinity of Jesus. As, thanks to a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the university underwent rapid expansion, enrolling students from around the globe, Dodge, an idealist alarmed by the growing factionalism, took to urging students to transcend their ethnic and religious horizons: “Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike need to have a spiritual awakening . . . so that selfish nationalism will be changed into team-work, corruption into public service, and indifference into a new faith.”

To no avail. An AUB alumna by the name of Hala Sakakini would later recall that civility between her fellow Arab and Jewish students began to disintegrate as conflict intensified in Palestine and pan-Arab identity hardened into uncompromising opposition to a Jewish state. In 1937, she writes, the 20th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration provoked a particular uproar on campus. Arab students skipped class to demonstrate on the streets of Beirut:

You knew beyond any doubt that every Arab student at the university, no matter what country he came from, belonged to one and the same nation—the Arab nation. . . . Every Arab became a Palestinian.

On the next anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, Jewish students wore the blue and white Zionist colors while Arab students wore black as a sign of mourning. According to a dispatch in the Palestine Post (later to become the Jerusalem Post), Jewish students who declined to remove their Zionist ribbons were threatened with violence. The undergraduate dean, Archie S. Crawford, blamed the Jews. Wearing Zionist colors, he intoned, had been “a tactless thing to do” on an occasion that was being “observed as a day of mourning by the greater proportion of our student body.”

In 1944, Stella Farhi—her father, Joseph Farhi, was a leader of the Lebanese Jewish community—submitted her master’s thesis at AUB on the topic of the “Jewish Problem.” What was the place of the Jew in modern society, she asked? Was Zionism a solution to the persecution of the Jewish people? She answered boldly that the correct solution to the Jewish Problem—indeed, the only solution—was Zionism: the self-determination of the Jewish people in their own land.

The realization of the Zionists’ dreams was what finally put paid to any further comity between the Arabs and Jews of AUB. In 1948, in the lead-up to Israel’s declaration of independence, a group of Arab students went to AUB’s vice-president to demand that Jewish students who were not nationals of Arab states be expelled from the university. The administration readily complied, “recommending” that, for their own safety, Jewish students leave; the Lebanese authorities officially concurred.

On his retirement in 1948, AUB President Bayard Dodge wrote an article for the Reader’s Digest, “Must There Be War in the Middle East?,” stating his own opposition to the creation of a Jewish state, an opposition based, he said, in his fear that such a move would provoke unrest in the (presumably otherwise placid) region. That year, there were 56 Jewish students enrolled at AUB—a drop from the early-20th-century high of 12 percent to 2 percent of the student body. Thereafter, the figure fell to fewer than 1 percent and, soon enough, to zero.

Some of the ongoing anti-Zionist upheavals at AUB in the 1940s and later will sound familiar to anyone who has recently witnessed anti-Israel events on an Ivy League campus: demonstrations, strikes, student occupation of campus buildings, and the like. But there was a difference. At AUB, some students also belonged to pro-Palestinian guerrilla organizations: either al-Fatah or its rival, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Indeed, George Habash, the founder of the PFLP, graduated from AUB in 1951 and would later credit that institution with raising his consciousness about the evils of the United States and Israel.

Two decades later, after the June 1967 war, an influx of Palestinian refugees into Lebanon fomented more internal violence. Refugee camps, filled with idle men, became hubs of guerrilla activity. When the PFLP and the Fatah leadership were expelled from Jordan in 1970, both sought refuge in south Beirut; there, the former joined the latter to become the second largest contingent in the PLO. Newsweek reported that AUB students spent weekends or whole summers in training camps for the now-unified organization. The magazine also reported students stealing chemicals from university laboratories to make explosives.

In July 1982, as the Lebanese civil war raged on, Hizballah kidnapped AUB president David Dodge, the son of Bayard Dodge, in retaliation for a kidnapping perpetrated by Christian Phalangist militiamen. Dodge spent a year in captivity, some of it in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison. In January 1984, Malcolm Kerr, Dodge’s successor as president (and himself the father of Steve Kerr, head coach of the Golden State Warriors), was brutally assassinated by Islamic Jihad.

The late Fouad Ajami, an eminent and much-mourned historian of the Middle East, would assign some of the responsibility for the rise of pan-Arab nationalism on the institutions founded by Protestant missionaries. “It was in the schools of the Anglo-American missions, and in the flagship of those missions, the Syrian Protestant College, that Arab nationalism had its start.” To Ajami, the movement, with its “thin veneer of superficial universalism,” was doomed from the start to burst at the seams, as historically it soon enough did. In the end, the only glue holding it together was hatred of the Jews.

As for the Jewish graduates of AUB, a number of them would go on to assume prestigious positions in the new state of Israel. These included Yehuda Cohen, who became a judge on Israel’s Supreme Court, and Eliyahu Elath, Israel’s first ambassador to the United States, both of whom graduated in 1944. Today, as Jews are effectively barred from studying at AUB, non-Jewish students from across the globe flock to the Jewish state for educational opportunities. Unlike Arab nationalism, Jewish nationalism was built from solid and stable foundations—even in so unlikely an environment as, once upon a time, Beirut.

Postscript:

In writing the above essay I relied on a number of books, articles, and private conversations to illuminate the little-known characters and events surrounding this period at the American University of Beirut. Among these works I would single out in particular Caroline Kahlenberg’s extensively researched article in Middle East Studies, “The Star of David in a Cedar Shield: Jewish Students and Zionism at the American University of Beirut (1908–1948).” Also useful were Brian VanDeMark’s American Sheikhs: Two Families, Four Generations, and the Story of America’s Influence in the Middle East (2012) and Betty S. Anderson’s The American University of Beirut: Arab Nationalism and Liberal Education (2011).

More about: Beirut, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism, Lebanon