Antoine-Jean Gros’s Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken in Jaffa, c. 1804. Wikimedia.

“The appearance of Bonaparte in Palestine was only like the passing of a terrible meteor, which, after causing much devastation, again disappears.”

This was the verdict of the great Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz in volume 11 of his monumental Geschichte der Juden (History of the Jews, 1870). He was referring to Napoleon Bonaparte’s short-lived invasion of Palestine in 1799.

Borrowing Graetz’s metaphor, the Zionist leader Nahum Sokolow (in his History of Zionism, 1919) thought it a pity that the meteor should have disappeared so quickly. Had Napoleon actually managed to establish an eastern empire including Palestine, wrote Sokolow,

perhaps he would have assigned a share in his government to members of the Jewish nation upon whom the French could rely . . . as having indisputable historical claims on the Holy Land and Jerusalem.

In this scenario of Sokolow’s, Zionism might have had a century’s head start. But, as he himself wryly concludes, “no Jew seriously believed in the success of Bonaparte’s ambitious designs or in the possibility of his victory.”

One possible reason for Napoleon’s failure was the plague. On Passover, Jews mark the exodus of the chosen people, launched at last on their journey toward the Land of Israel, from an Egypt that had been visited by ten plagues. Napoleon was a chosen person who proceeded from Egypt to invade the Land of Israel, only to be thwarted there by a plague. It’s a reminder—as if we needed one at this moment—that politics and plagues are inseparable.

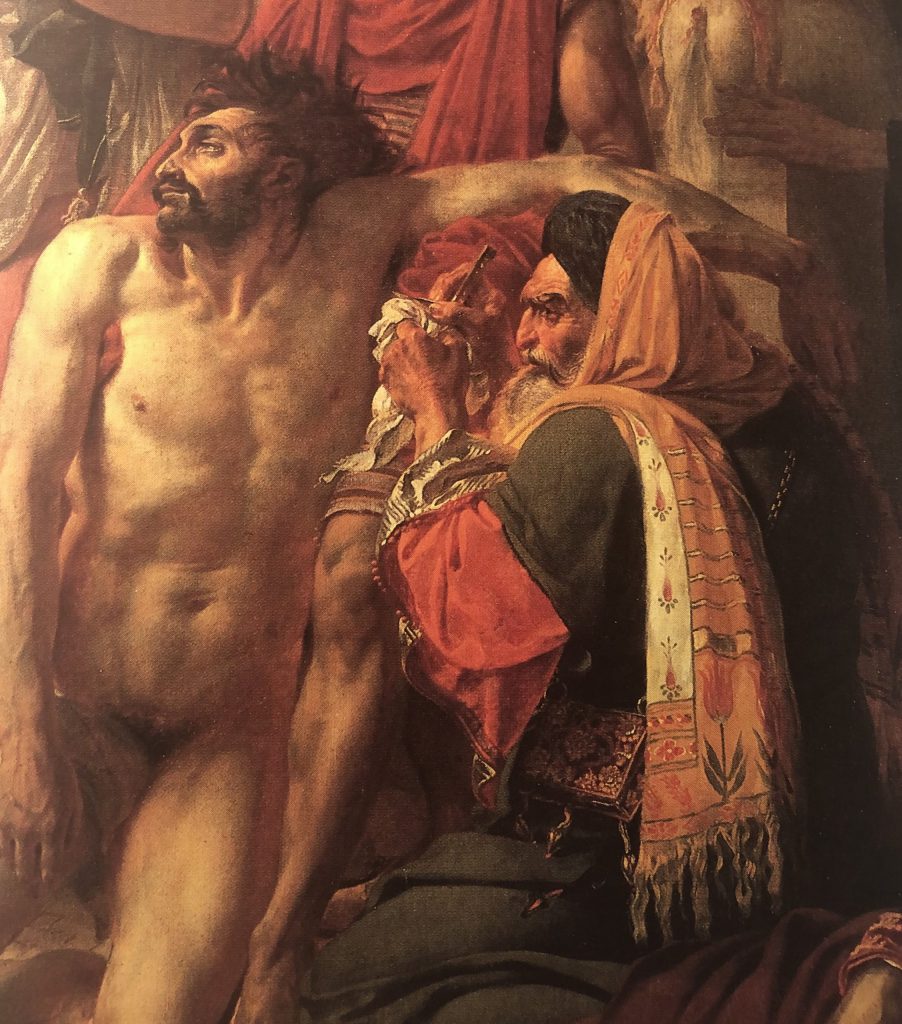

The ancient story, the one about the Jews, is preserved in sacred texts; the modern one, about Napoleon, is preserved in an immortal painting. Prominently displayed in the Louvre in Paris, it depicts an event that took place in Jaffa, now a part of Tel Aviv. Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken in Jaffa was painted by Antoine-Jean Gros in 1804. At the time, it was a sensation; today it remains the subject of enduring fascination.

The date is March 11, 1799, in the midst of the French invasion of Ottoman Palestine. At the center of the painting is the twenty-nine-year-old Napoleon (then still known modestly as General Bonaparte), who the previous year had seized Egypt as part of a plan to checkmate Great Britain, then at war with France and soon to be allied with Ottoman Turkey. A British fleet had cut off Napoleon’s force; to escape the closing noose, he marched across the Sinai and invaded Palestine.

Reaching Jaffa, the French army overcame resistance by the local Ottoman garrison and conquered the town by storm, pillaging left and right and, on Napoleon’s order, massacring several thousand Muslim war prisoners. (This butchery inspired a 1934 play, Bonaparte in Jaffa, by the German-Jewish novelist and playwright Arnold Zweig.) In the aftermath of the mayhem, many dozens of French troops fell ill with the bubonic plague, which had been endemic in their ranks even in Egypt.

This is the point at which the painting, a huge neoclassical masterpiece, comes in. Napoleon, in uniform and accompanied by his aides, is visiting a makeshift ward of desperately ill French soldiers. It is a scene of abject misery and physical suffering. A shaft of light illuminates the general as he fearlessly extends his bare hand to touch a bubo (an inflamed lymph node) of an infected soldier. Behind him, an officer holds a handkerchief to his nose, to block the stench or to protect against contagion. But Napoleon himself is undeterred.

The scene is loosely based on a real event reported by the French army’s chief medical officer:

The general visited the hospital and its annex, spoke to almost all of the soldiers who were conscious enough to hear him, and, for one hour and a half, with the greatest calm, busied himself with the details of administration. While in a very small and crowded ward, he helped to lift, or rather to carry, the hideous corpse of a soldier whose tattered uniform was soiled by the spontaneous bursting of an enormous abscessed bubo.

The effect of the painting, to anyone who’s viewed it in the Louvre, is searing. Not only is the image of Napoleon himself unforgettable, but the rest of the canvas, which measures roughly 23 x 17 feet, painstakingly depicts each horrifying stage of the plague’s afflictions while also offering an ethnographic rendition of the “Orientals” on the scene.

Still, as unforgettable as is the artistic achievement, it’s been a long time since the event depicted by it has spoken to contemporary concerns. Perhaps now, however, it does. In what follows, I’ll restrict myself to five aspects that may have escaped notice in the past but that resonate in this COVID-19 moment. I’ll then conclude with a rumination on a question never asked before: by some twist of historical logic, could the event captured by Gros have been good for the Jews?

The Five Aspects

First, social distancing. It’s easy to see the centerpiece of the painting as alluding to Napoleon’s semi-divinity. Gros finished his commission in the months just prior to the spectacular coronation of Napoleon as emperor in the cathedral of Notre Dame. Is that outstretched hand not the healing hand of Jesus, who in various Gospels heals leprosy, blindness, and deafness by the touch of his hand? Or is it perhaps the miracle-working (thaumaturgic) touch of French kings? At the very least, it betokens an act of death-defying courage.

That interpretation is contradicted, however, by the shadowy presence of a third person between Napoleon and the afflicted soldier: namely, the army’s chief medical officer, René-Nicolas Dufriche Desgenettes. Gros portrays him as an island of calm amid the chaos. His own hand seems to be cautioning Napoleon without actually restraining him.

And that’s because Napoleon has relied on the medical officer’s expert advice. At the time, no one knew that the plague was transmitted via infected rats and their fleas. But Desgenettes already suspected that human contact wasn’t what accounted for its spread. “I was not at all convinced of the very easy transmission of the disease,” he would recall.

How could Napoleon convey this confidence to his troops and thereby banish their panic? He could lead by example. His touch wasn’t intended to heal the sick—for that, they needed doctors (and to judge from the scattered bodies, the odds were against them). It was to show the healthy that they could care for the ill and, more importantly, march alongside their fellow soldiers without fear of contagion. Behold, Napoleon’s gesture says, I am mortal, but I don’t fear transmission—and neither should you.

So Napoleon listened to his expert, and then, by his outstretched hand, amplified the expert’s message to his “public.” For all of the general’s pretensions, he respected expertise. Indeed, he had packed his expedition to Egypt with savants from every useful field. They not only solved many of the army’s immediate problems but later also gave Europe its first accurate picture of Egypt past and present.

And what about us? In recent weeks, we’ve seen our own leaders on stage with their medical experts. At times, it’s been disconcerting. But as Napoleon showed, a leader can hold ill-informed medical opinions and still heed experts when it matters. Napoleon stated his own belief that

all those whose imagination was struck by fear [of the plague] died of it. The surest protection, the most efficacious remedy, was moral courage. . . . The best way to preserve the army from the disease was to keep it on the march and occupied.

This was obviously nonsense. Fortunately for his army, it didn’t prevent Napoleon from ordering practical measures of hygiene that inhibited transmission.

Once back in Egypt, Desgenettes would clash with Napoleon over the general’s attempt to shift blame for his defeat in Palestine onto the plague—and the doctors. In a meeting with his scholars, Napoleon reportedly called medicine “the science of assassins,” practiced by “charlatans.” Desgenettes defiantly replied: “And how would you define for us what conquerors are?” The exchange left Napoleon “pale with rage.”

In brief: tensions between leaders and their medical advisers are nothing new.

Second, the (fill-in-the-blank) virus.

The bubonic plague and COVID-19 belong to different centuries. Thanks to modern hygiene and antibiotics, the plague has largely disappeared. But in the popular imagination, today’s coronavirus does share something with yesterday’s plague: both are thought to be diseases inflicted on the West by the Orient.

Why? In the early 18th century, the plague disappeared from Western Europe, and by mid-century the Habsburgs had created a cordon sanitaire that kept it out of central Europe as well. But it continued to ravage the Ottoman empire. The entry on “plague” in Diderot’s great French Encyclopédie from the mid-18th century doesn’t mince words:

Plague comes to us from Asia, and for 2,000 years all the plagues that have appeared in Europe have been transmitted through the communication with us of the Saracens, Arabs, Moors, or Turks, and none of our plagues has had any other source.

Istanbul in particular, with its huge bazaars, was reputed to be a hub of contagious disease; in Mary Shelley’s apocalyptic novel The Last Man (1826, published after her Frankenstein), a world-devastating plague begins there. Ottoman Egypt had a similar reputation: in Cairo, a major outbreak of bubonic plague in 1791 killed a third of the inhabitants.

So Europeans in Napoleon’s day looked upon the plague as “Oriental” or “Turkish.” In this case, the plague that afflicted Napoleon’s troops wasn’t imported; instead, the French had intruded upon a Turkish domain, as Gros’s painting acknowledges. Although the depicted ward was actually located in an Armenian convent (which still stands), Gros puts it under a looming minaret in what appears to be the courtyard of a mosque, surrounded by Islamic-style arcades. But beyond and above the scene flies the French tricolor, and all the victims are French. Which is to say: although France had invaded the land of the Turks, “their” plague had invaded French bodies.

In this sense, the finger-pointing of today, as in references to the “Chinese virus,” enjoys a longstanding pedigree. In addition, the finger-pointing has always been bi-directional: in the Ottoman empire, syphilis was called the “Frankish pox.”

There is another parallel with today in the evasive language used to describe the affliction. Napoleon and his doctors knew that this was the bubonic plague (peste), and the title of Gros’s painting refers to Napoleon visiting the plague-stricken (pestiférés). But at the time, Napoleon’s medical team was careful not to call it that, lest it create panic in the ranks. Instead they called it bubonic fever (fièvre), “such that the army remained convinced that it was not the plague.”

This will sound familiar to anyone who’s heard COVID-19 described as “the flu.”

Third, the Wisdom of the East.

Gros did introduce an element that complicated his identification of the plague with the “Orient.” In the foreground, there is a handsomely attired Turk or Arab, calmly ministering to a French patient. (He is incising a bubo, a standard treatment at the time.) Academic formalists once regarded Gros’s inclusion of this person as a flaw, distracting the viewer from Napoleon and the nude soldiers. In more recent times, post-colonial critics have imagined that the figure’s detached demeanor is somehow meant to suggest “Oriental fatalism.”

But in today’s circumstances, another possibility leaps to mind. Who but a Turk would be most knowledgeable about the “Turkish” plague—so much so that a French artist might depict him treating a French patient? (By contrast, a French doctor in the lower corner of the canvas is dying.) French sources recorded that this captive barber-surgeon, from Istanbul, “carried out dangerous operations in the plague-stricken hospitals” even though his instruments dated “at best to the end of the 16th century.”

Anyone who has seen headlines about the lessons to be learned from South Korea and Singapore will detect a faint echo of Gros’s Turkish surgeon, who reminds us that, like it or not, “we’re in this together.”

Fourth, forbidden triage.

This aspect of things is represented not in the painting but by the painting.

From Jaffa, Napoleon next proceeded to Acre and laid siege to it, but unsuccessfully. In his hurried retreat southward, wounded and sick soldiers died horrible deaths on the wayside. Back in Jaffa, he visited the quarantine ward once again. While accounts differ widely, the general seems to have suggested to Desgenettes that the plague-stricken French soldiers be given poison since they couldn’t be transported to Egypt and would otherwise fall into sadistic Turkish hands. Moreover, recalled Napoleon’s private secretary, “to bring them with us, in the state that they were in, would have been tantamount to infecting the rest of the army with the disease.”

Desgenettes refused: “My trade is to heal men, not kill them.” But there is also testimony that an army pharmacist offered a toxic mix to several dozens of soldiers. When the Turks arrived, along with some British advisers, they reportedly found some surviving French soldiers and from there spread the story of Napoleon’s poisoning of his own men.

The British, for their part, were quick to use this as propaganda against “Boney” in printed caricatures of the scene. One, from 1803, shows Napoleon in the Jaffa ward, ordering a horrified doctor to administer opium in order to poison “Five Hundred & Eighty of his wounded Soldiers.” The story almost certainly circulated in France as well as in the French army.

Whatever the truth of the story, it raises a question that seems newly urgent today: what trade-offs should be made in the midst of shortage? In planning his retreat, Napoleon had limited resources and wanted to protect a vulnerable army. Should he have risked the living by taking with him the desperately ill?

Today this is called medical rationing. An older name is triage, from the French trier, to sort or select. It emerged from the Napoleonic wars but had an earlier trial run in Palestine, where the French suffered huge losses to battle and disease, and a wounded army had to retreat through hostile territory and burning desert. In fact, Dominique-Jean Larrey, the French surgeon usually credited with inventing triage, served under Napoleon in Palestine. In his own memoir of the campaign, he held that no live Frenchman was left behind at Jaffa.

Wherever triage becomes necessary, leaders and physicians will inevitably wind up reenacting exactly the same debate that erupted in the Jaffa pesthouse.

Fifth, plague and propaganda.

This aspect brings us to the back story of the painting itself. Napoleon is thought to have commissioned the work precisely in order to refute the nasty rumors about Jaffa. He probably also approved one of Gros’s preliminary studies.

For greater effect, Gros himself took liberties with the storyline: in an early study for the painting, Napoleon carries a corpse (as reported by Desgenettes). But Gros apparently decided it would be unseemly or lacking in drama for Napoleon to be shown dragging a body, and so he substituted the general’s resolute touch of the standing soldier.

Gros’s sensational masterpiece, completed over six months in 1804, was exhibited in that year’s Salon, a juried art fair held every two years at the Louvre. The Salon wasn’t aimed only at highbrow critics. An Englishman who attended that year wrote: “It is open to the public at large, and is crowded with soldiers, day laborers, and poissardes [fishwives].” This was a bully platform, and the most potent mass medium of the day.

Gros’s painting was the hit of the show. Later, it would be reproduced in prints and engravings, and would find its way in miniature to mantlepieces across France. Meanwhile, the Jaffa convent would become a standard tourist stop for French travelers who had seen some version of Gros’s painting.

Of course, the painting itself was blatant propaganda, depicting a disastrous military campaign as a test that forged Napoleon into a fearless leader. And many other artists would be commissioned to produce similar works, cherry-picking Napoleon’s victories over Egyptian armies and rebels, forgetting or ignoring the overall incoherence of his strategy. Because the Palestine campaign was particularly thin on battlefield success, Gros’s painting of the pesthouse came to replace it.

The message: Napoleon may not have conquered the Turks, but that wasn’t his fault. See the bodies? He was battling the plague! Although the plague, as one contemporary critic wrote, was “an enemy the French bayonet cannot reach,” Napoleon had nonetheless conquered fear of it.

No one today knows exactly when the COVID-19 “war” will end. But it seems certain that in its aftermath we’ll be subjected to a similarly massive campaign seeking to persuade us how fortunate we were to have the political leaders that we did. We might not be asked to crown them as emperors, but we will surely be summoned to vote for them.

Still, once Napoleon met his Waterloo—the real one—the critics finally drew their knives for Gros’s painting as well, denouncing it as a fraud. “Several army officers have assured me that the scene was pure fiction,” recorded the writer Chateaubriand in his memoirs. “What becomes of Gros’s fine painting? It remains a masterpiece of art.” And what became of Gros? His star dimmed after Napoleon’s fall, and in 1835 he drowned himself in the Seine.

Was It Good for the Jews?

Were it not for the bacterium (Yersinia pestis) that caused the plague in Napoleon’s ranks, might Zion have been restored to the Jews more than a century before the Balfour Declaration?

Thanks to the historian Graetz, who retailed the story, many came to assume that Napoleon, while campaigning in Palestine, did in fact make a promise to restore the country to the Jews. The evidence for such an offer is so ambiguous that its existence will never be established with certainty. Some scholars argue that the promise left too many traces not to have existed; others detect forgery.

But, assuming for the sake of argument that the promise did exist, did the plague in the French army, like the plagues in the book of Exodus, alter the course of Jewish history? On the one hand, Napoleon himself might have nodded “yes.” He preferred to attribute the Palestine disaster to the plague, and Gros’s painting lent him support. And yet, on the other hand, it’s long been the consensus of military historians that in Palestine the general was outnumbered, outgunned, outmaneuvered, and (least flattering of all) outgeneraled. Moreover, since only about 15 percent of his force contracted the plague (which wasn’t always fatal), disease didn’t make a decisive difference to the outcome.

In retrospect, the entire expedition to Egypt seems to have been a folly, so how could its chaotic extension into Palestine have been anything different? Yet Graetz’s (and Sokolow’s) metaphor of a disappearing meteor may also fail to do the Palestine campaign justice. Rather, like a stone tossed into a stagnant pond, it can be seen as sending ripples to and fro.

Specifically, the Palestine expedition made the Holy Land an arena of European competition, potentially opening a door to the Jews. “After Napoleon,” wrote the historian Barbara Tuchman, “it became axiomatic that whenever the powers fell to fighting in the Middle East, someone would propose the restoration of Israel.” In the 19th century, as the Ottoman empire became the “sick man of Europe,” such proposals, characterized not as Zionism but as Restorationism, proliferated.

Later, Zionists themselves played up the slender evidence of a Napoleonic offer in order to stimulate wannabe Napoleons to make such an offer themselves. Thus, Theodor Herzl wrote to Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1899:

The idea I serve has already touched a great monarch in this century: Napoleon the First. . . . Was the matter not yet ripe at the time, was there no resolute representative of the Jews, was it due to the paucity of means of communication? Our time, however, is under the sign of communication! . . . The Jewish Question must be brought under this sign; this is how it can be solved. And what was not possible under Napoleon I is possible under Wilhelm II!

The Kaiser didn’t bite. In 1915, in the midst of World War I, when Zionists were explicitly seeking a British promise of Palestine, the Anglo-Jewish writer Israel Zangwill tried another tack. As no British leader could be persuaded to emulate the detested Napoleon, Zangwill summoned the emperor’s ghost to shame Britain into action:

Napoleon, under the spell of the 40 centuries that regarded him from the Pyramids, announced his design to restore the Jews to their land. Will England, with Egypt equally at her feet, carry out the plan she foiled Napoleon in?

Two years later, with the Balfour Declaration, she did. Lloyd George, the prime minister whose government issued the declaration, explained in 1925 why it eclipsed any promise made by Napoleon. Declining to judge whether Napoleon’s offer was a fiction, he insisted that, even if true, it lacked the pro-Jewish conviction behind the Balfour Declaration.

“We had been trained even more in Hebrew history than in the history of our own country,” Lloyd George wrote:

I was brought up in a school where I was taught far more about the history of the Jews than about the history of my own land. . . . So that therefore, when the question was put to us, we were not like Napoleon, who had never been in a Sunday school and had probably read very little of that literature. . . . I will tell you the difference between the Balfour Declaration and Napoleon’s promise. . . . Napoleon never kept faith if it did not suit him. . . . The Jews knew the signature of Napoleon was not of much use, but they also know the British signature is invariably honored.

Given the subsequent history of the British Mandate, “invariably” may be too strong a word. But no Zionist at the time thought the French would have done better.

Could it be then, that Napoleon’s adventure, by its failure, advanced the restoration of the Jews? By invading Palestine, Napoleon put the country back on the geopolitical map; by retreating in defeat, he left the door open to Britain, a steadier patron of Zion. Napoleon’s debacle kept the Land of Israel out of the French orbit until such time as the more faithful British assumed the burden of promoting a Jewish “national home.”

To be sure, I’m engaging in counterfactual hindsight, the obliging servant of history. Still, if any credence at all is to be placed in such a reading, then perhaps Israelis and Jews today should be grateful for the plague that made some incalculable contribution to Napoleon’s defeat. And if that is so, then perhaps the proper Jewish way to view Gros’s Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken in Jaffa is with a sense of déjà vu: for the second time in history, the Jewish people were saved by a plague afflicting the minions of a tyrant of Egypt.

Try that on for size during your next visit to the Louvre.