Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

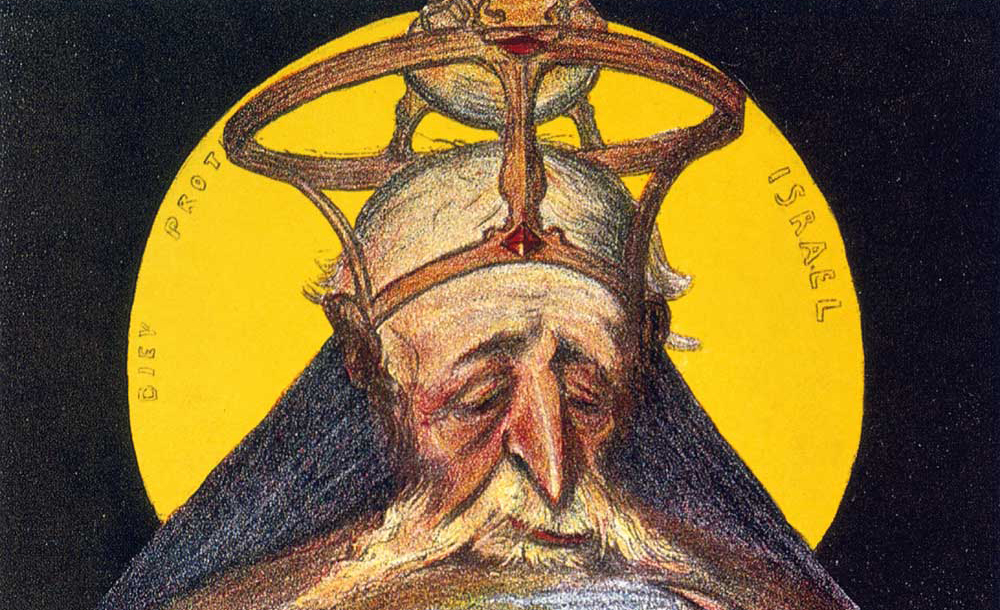

A recently discovered letter in the archives of the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem sheds light on why the entry “antisemitism” did not appear in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, whose initial “A” and “B” volume was published in 1888. The OED ignored the word even though the German term Antisemitismus had been introduced into European discourse nearly ten years earlier, in 1879, by the political activist and publicist Wilhelm Marr in his pamphlet Der Weg zum Siege des Judenthums über das Germanenthum (“The Way to the Victory of Judaism over Germanism”) and had already been picked up by other languages, English included.

The discovered letter was an answer sent in 1900 by James Murray, the OED’s editor-in-chief, to the Anglo-Jewish leader Claude Montefiore, who had inquired why “antisemitism” was missing from the dictionary. Murray’s answer was admirable. Marr’s coinage, he wrote, was but one of many “anti-” words that had not made it into the OED because there was a plethora of these and he had not thought that it or the phenomenon it referred to would last. “Would that [the word] antisemitism had had no more than a fleeting interest!” he now wrote to Montefiore, admitting his error. In actuality, he stated, “the closing years of the 19th century have shown, alas!, that much of Christianity is only a temporary whitewash over brutal savagery.”

Looking back from the early 21st century, we can also utter an “alas” over the unfortunate word “antisemitism” itself, which was invented by Marr in place of the older German term Judenhass, “Jew-hatred,” because he wished to associate such hatred with the new racial ideologies that were gaining intellectual acceptance in his day. Whereas once, the implication was, such hatred had been understood to stem from the religious conflict between Christianity and Judaism, the time had come to realize that it in fact derived from a struggle between the Aryan race and the Semitic one, of which the Jews were the foremost representatives.

This of course makes “anti-Semitism” (to use what has become the preferred spelling) a literally racist term in its own right, along with its derivatives “anti-Semite” and “anti-Semitic.” It is indeed an absurd term, since Jews, with their admixture of genes from all over, have long ceased to be a distinctly Semitic people—certainly less of one than are tens of millions of Arabs whose ancestors never left the Middle East. (Hence, the common Arab protestation, “We can’t be anti-Semitic because we’re Semites ourselves,” which is both comically disingenuous and, technically speaking, perfectly correct.)

But there is another and I think more important reason why Judenhass or “Jew-hatred” was a descriptively better term than the “anti-Semitism” that replaced it. This is that anti-Semitism is simply too imprecise. While we all know what hatred is, being “anti”-something or -somebody is an extremely vague notion that can include quite disparate attitudes and feelings.

This is certainly true of “anti-Semitism.” There is a great difference, after all, between someone who thinks, say, that Jews care too much about money and someone who thinks that the Jews are eternally responsible for the death of Jesus or engaged in a conspiracy to take over the world. A person with Jewish friends and the belief that biblical monotheism was a historical misfortune is not the same as a person convinced that the Bible is God’s revealed word and that Jews should be barred from his country club. It is one thing to say that Jews are clannish and another to approve of their having been sent to the gas chambers. Some people truly hate Jews, some dislike aspects of what they take to be Jews’ behavior, others may have neutrally colored misconceptions about the Jews, and other still may criticize them unjustly in certain contexts and defend them in others. Is there anything to be gained from lumping such dissimilar types under a single rubric?

We don’t generally do this with prejudices regarding other ethnic or national groups. If I say “The British are frightfully stuffy,” I’m not automatically classed with someone who says, “The British are the scourge of civilization.” I may be about to add in my next sentence, “But they’re also very kind-hearted”—and even if I’m not, my feelings about England may be sufficiently complex or contradictory to rule out being accused of “anti-Britishism.” Yet let someone say, “Jews are argumentative,” or “Jews aren’t good at sports,” and right away he or she is put in the same semantic category as someone who says, “The Jews are as bad as the Nazis.” All are anti-Semites.

At this point in history, there’s not much we can do about this. We’re not living in the age of James Murray and we can’t go back to the term “Jew-hating,” even if it makes a badly needed distinction between people who share a strong animus toward Jews and people who don’t. “Anti-Semitic” is a term we are stuck with, and the only word that has lately been offered in its place, “Judeophobia,” is no improvement. Would we really want to suggest that every time someone stricken with the condition it describes sees a Jew—as “Islamophobia” suggests vis-à-vis Muslims—he wants to scream with fright and run the other way?

Still, we would be using the term “anti-Semitism” more discriminatingly if we occasionally reminded ourselves that “Jew-hatred” was its antecedent. When the mayor of New York gets upset with “the Jewish community” because some of its members aren’t observing social distancing, he may be unfair, but he is not being hateful. When the leader of the Nation of Islam calls Jews termites, he is. Either we reserve the term “anti-Semite” for those who truly despise the Jewish people, or we are forced to acknowledge that we often employ it for real or perceived infractions that are, relatively speaking, not such a big deal.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Anti-Semitism, History & Ideas