Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Mosaic reader Shelly Rosen writes:

“My zeyde always drank a schnaps before dinner and said he was drinking a ‘brunfin,’ or maybe a ‘brunfun.’ Do you think there is any connection between this word and the whiskey-making Bronfman family of Canada? And what is the word’s correct form?”

The correct form of the Yiddish word, which means “liquor,” is bronfn or bronfen, with the first vowel pronounced like the “o” in “for” and the second like the “o” in “reason,” and while it seems logical that the Bronfmans—the erstwhile owners of the Seagram Company, once the world’s biggest liquor manufacturer—should owe their family name to it, this is far from certain. But I’ll get back to that.

Yiddish bronfn derives from German Branntwein, a shortening of gebrannt Wein or “burned wine.” (Its English cognate of “brandy,” itself a shortening of “brandywine,” comes from the similar Dutch word brandewijn.) The “burning” that produces brandy is the process of distillation, practiced since the late Middle Ages, whereby wine is heated in a pot or vat to the point that its alcohol, which has a lower boiling point than water, evaporates along with certain volatile compounds, after which they are re-condensed by being passed through a chilled tube, sometimes distilled a second time, and often aged in casks. The resulting product, naturally, has a higher alcohol concentration than the beginning one, which is why the “proof” or percentage of alcohol in most brandies is three to four times that of the proof of most wines.

True brandy is made from grapes, and while one also speaks of various other fruit brandies, such as plum brandy, apricot brandy, and so on, these are brandies by virtue of their method of manufacture, not of their ingredients. Still other distilled liquors, such as vodka (made from potatoes or grain), scotch (barley) or rye whiskey, bourbon (corn, wheat, and barley), rum (sugar cane), etc., are never referred to as brandies at all. Bronfn, however, can denote any of these drinks, although in Yiddish-speaking Russia and Poland it almost always meant vodka, which was the only liquor that anyone but the wealthy drank. When one reads in translations from Yiddish of Jews in Eastern Europe drinking brandy, this is generally a translator’s mistake.

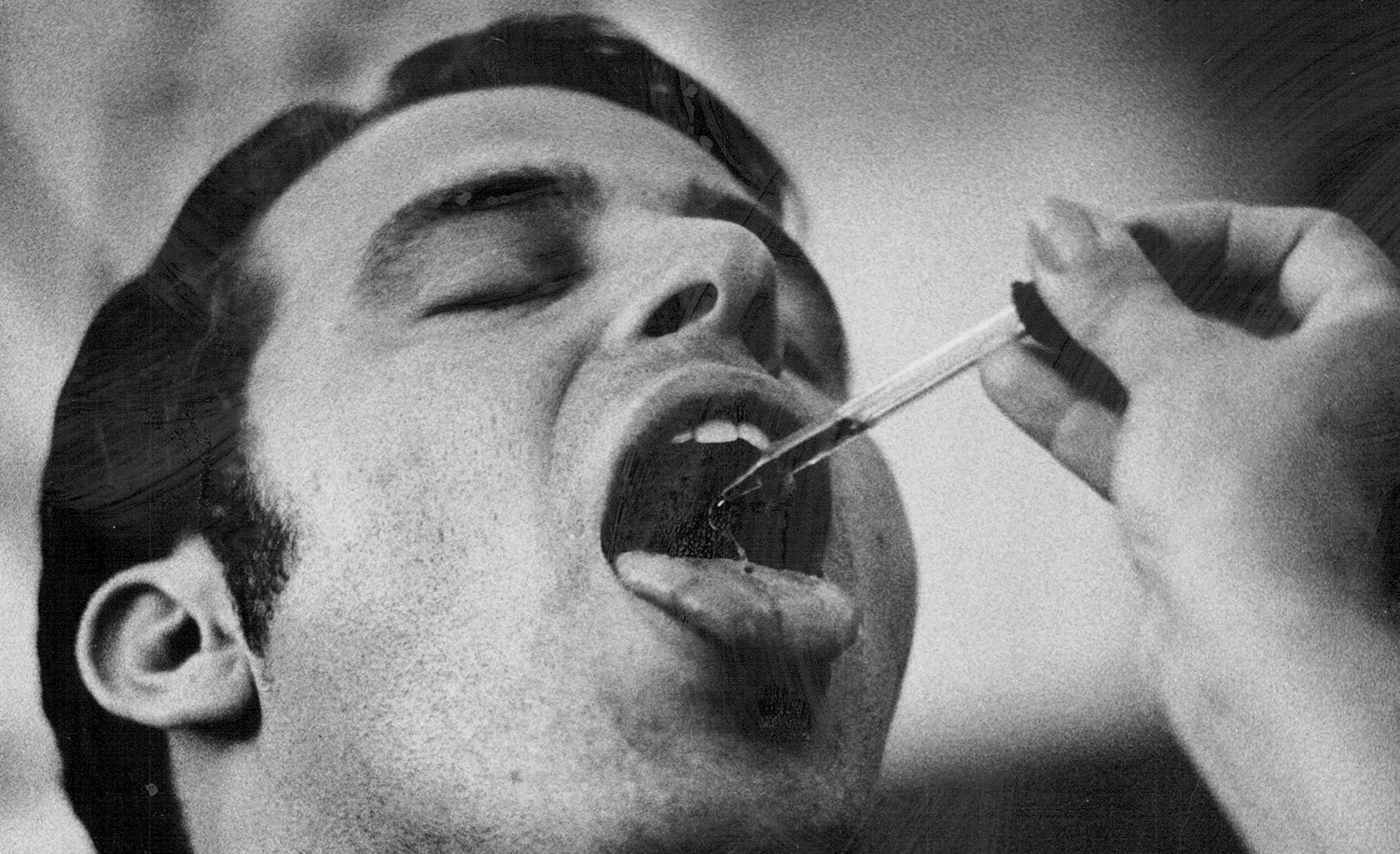

Apart from bronfn, Yiddish has several other words for liquor. One, the “schnaps” that Ms. Rosen remembers her grandfather drinking, is German-derived, too. It comes from the verb schnappen, a cognate of English “snap,” one of whose meanings is to bite off, and Schnaps originally meant a bite or mouthful of something; then, a mouthful of liquor; and ultimately, liquor itself. As used by Germans, who did not traditionally drink vodka, the word denoted brandy or aquavit, and in Yiddish, too, shnaps more often referred to such drinks than to vodka. Yet the demarcation between shnaps and bronfn is blurry and the two can be interchangeable. I can’t promise Ms. Rosen that her grandfather’s bronfn wasn’t the Scotch that is the preferred drink of many American Jews.

Two other common Yiddish words for liquor derive from Hebrew. The first of these, máshke, comes from mashkèh, which simply means “beverage” or “drink.” (In contemporary Israeli Hebrew, liquor is mashkeh ḥarif or “strong drink.”) Yet already in the Bible, mashkeh has alcoholic connotations. When we read in the book of Genesis about Pharoah’s sar ha-mashkim, his cupbearer or “chief butler,” as the King James Version calls him, we are not reading about a maître d’ who brought him fruit juice. The word “butler” is an old English form of French boutellier, from bouteille, which nowadays means a bottle but once meant a wine cask, and the King James had it figured out right.

The second Hebrew-derived word is yash, an acronym of yayin saruf, “burned wine.” The term is found often in rabbinical literature, the oldest attested-to example of which is Tsvi Hirsh Kaidanover’s book of moral homilies Kav ha-Yashar, “The Straight Line,” published in 1706 in Frankfurt. There Kaidonover tells a story about a mohel, a ritual circumciser, asked to circumcise a newborn child whose father, unbeknownst to him, is a demon. Arriving at the village of the demons, all disguised as human beings, the mohel performs the ritual and is then invited to the home of the sandak, the child’s godfather, where “sweets and yayin saruf” are served. The story ends happily, though (just in case Kav ha-Yashar is on your reading list) I won’t spoil the suspense by telling you how.

Yash is a fine old word, and it’s a shame that it has disappeared from the Hebrew of Israel along with many other fine old Hebrew words and expressions. Not that Israelis say brendi instead. Their word for brandy is konyak, spelled cognac in English, and I’m surprised they haven’t had a lawsuit filed against them, since the makers of genuine cognac—brandy produced in the Cognac region of France—have lately been taking distilleries to court left and right for appropriating the name.

In this case, I’ll stick up for Israel. My favorite Israeli konyak, gone for years now, used to be a cheap, local brand named 777, which sold for about $10 a bottle. Back in the days when it was still on the shelves, my wife and I were once invited to dine at a wealthy home in France, where after dinner our hosts brought out a $300 bottle of Armagnac—a brandy, nearly as famous as cognac, made in the region next-door. To my everlasting pride, as my wife will testify, I turned to her after drinking a glass or two and whispered, “777 is better.”

To return, though, to the Bronfmans: the main problem with assuming that their name comes from bronfn is that, by all official accounts, when Yechiel and Mindl Bronfman, the parents of Seagram’s founder Samuel Bronfman, immigrated to Canada from the Russian province of Bessarabia in 1898, their business was tobacco farming, not liquor manufacturing. Could there have been bronfn makers in the family that no one knows about? That’s possible but unproven. Although Samuel started his career as a bootlegger during Prohibition, any bootlegging ancestors, if they existed, covered their tracks well. They would have had to, like Samuel, in order to avoid the law, since the production of vodka in tsarist Russia was a state monopoly and you wouldn’t want to have been caught peddling moonshine bronfn.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Alcohol, History & Ideas, Yiddish