Got a question for Philologos? Ask him yourself at [email protected].

A friend mentioned being surprised the other day to hear of Ukrainian refugees being taken in by families in the Polish city of Chełm. “I never knew there actually was such a place,” he said. “And even if there was, I’d have thought its reputation would have caused it to change its name.”

Yes, there is a place called Chełm—located, Wikipedia tells us, “in southeastern Poland . . . some 25 kilometers from the border with Ukraine” and home to 63,949 inhabitants, who pronounce its name “Khewm.” (Yiddish speakers said “Khelem” or “Kheylem,” as do knowledgeable Jews today.) And they have no need to be embarrassed, since, writes the North Carolina University associate professor Ruth von Bernuth in her 2016 book How the Wise Men Got to Chelm: The Life and Times of a Yiddish Folk Tradition, “in non-Jewish Polish culture, Chełm as a town full of fools in unknown.”

What surprised me even more in reading von Bernuth’s book was to learn that even among Jews, the town of Chelm was unknown as a proverbial Foolsville until the last third of the 19th century. This makes it an extreme latecomer to the long list of towns legendary for their simpletons, of which the oldest on record is Abdera in classical Greece. A butt of ancient Greek humor, Abdera, von Bernuth tells us, was first introduced to European readers by Christopher Martin Wieland’s comic 1781 History of the Abderites—and when, my curiosity piqued, I turned to Wieland’s book, I indeed felt that I could have been reading about the wise men of Chelm.

For example: Wieland tells the story, culled from Greek sources, of how, having ordered a statue of Venus from the great sculptor Praxiteles, the Abderites thought it too beautiful to be casually displayed on ground level and built an 80-foot-tall obelisk on which to place it. The result? “Although it was now impossible,” Wieland writes, “to discern whether the statue was supposed to represent a Venus or an oyster, the Abderites nevertheless obliged all visitors to admit that nothing more perfect could be seen.”

If one were to substitute for Praxiteles’ statue a finely wrought silver spice box or Hanukkah menorah, could not this have happened in Chelm? And Wieland could be describing the Chelmites, too, when he writes:

The Abderites never lacked ideas, but rarely were their ideas suitable to the occasion where they were applied. . . . If they did something especially foolish (which happened rather often), that was generally the result of their wanting to do things all too well; and whenever they deliberated earnestly and at length about matters concerning their community, one could with certainty count on their coming to the worst of all possible decisions. . . . They finally became a byword among the Greeks. An Abderite inspiration or an Abderite trick meant to them approximately what we mean by the expression a Schildbürger imbecility or the Swiss by a Lalleburg foolishness.

This last sentence refers to Wieland’s literary predecessors, from which he took some of his material. The imaginary town of Lalenburg and the real town of Schilda in the Brandenburg region of Germany were essentially the same place, the subjects of a book, published in 1597 as Das Lalebuch (“The Lale Book”) and in 1598 as Die Schiltbürger (“The Citizens of Schilda”), which ascribed a humorous compilation of Abdera-type tales to a locality in Germany. The volume, von Bernuth relates, was highly popular and spawned numerous imitations and adaptations. Some were in Yiddish, of which the archetype, dating to 1727, bore the concise title Vunder zeltzame, kurtzvaylige, lustige, unt rekht lakherlikhe geshikhte unt datn der velt bekantn Shild burger, that is, “Wonderfully rare, brief, hearty, and quite laughable stories and facts about the world-famous burghers of Schilda.”

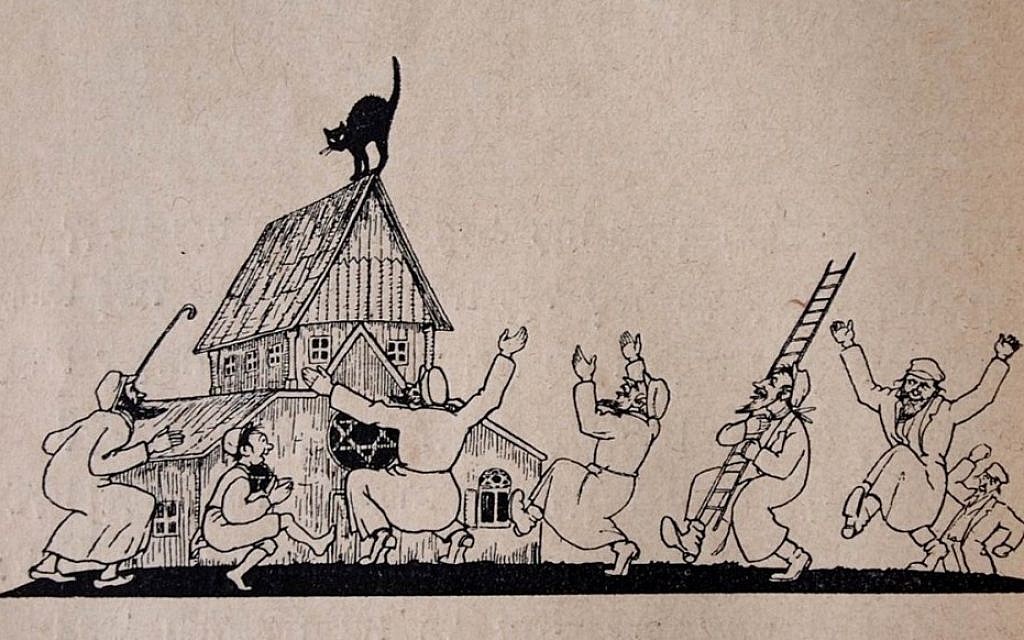

These Yiddish versions of the Schildburg stories circulated widely and made their way into Jewish folklore, where many were eventually transformed into Chelm tales. Von Birnuth cites the case of the Schildburgians who built a magnificent new town hall, the interior of which, when the building was finished, was inexplicably dark. Not realizing that the reason was their failure to include windows in the structure, they first sought to bring in bags of daylight to dispel the gloom and then, when this stratagem failed, tore down the roof to let in the sun—which worked well enough until winter arrived. A similar anecdote, its town hall changed to a synagogue, is part of the Chelm corpus.

Yet Chelm itself does not originally seem to have been part of this corpus. For centuries, Foolsville stories were told about other heavily Jewish towns in Central and Eastern Europe, such as Metz, Fürth, Prague, and Poznan, all of which were ridiculed by other Jews. The first known reference to Chelm as such a place dates to 1873—and this, too, was not a Jewish one. It was made by Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Wander’s Deutsche Sprichwörter Lexikon (“Lexicon of German Proverbs”), which had an entry for the Yiddish phrase Chelmer narrunim (“the fools of Chelm”), of whom it stated: “The town of Chelm in Poland has a reputation similar to that of Schilda, Schöppenstedt, Polkwitz, and [other similar] places in Germany. Many amusing stories about it, comparable to the antics of the Abderites and to what has been written about Schilda, are in circulation.”

Why Chelm, at the time a typical Polish shtetl whose 5,000 or so Jews comprised over half its population, was singled out in such a way is something that von Burnuth confesses to being unable to explain. Nor is it entirely clear why, within several decades, it pushed its competitors aside and came to be considered a uniquely foolish place. A contributing factor was certainly the Yiddish writer and folklorist Menachem Kipnis, who in the 1920s published an immensely popular series of Chelm stories in the mass-circulation Warsaw newspaper Haynt. Kipnis’s tales included nearly all the classics of the genre, such as the story of the Chelmites who sought to trap the moon’s reflection in a barrel from which they could take it out to shine on moonless nights, or who decided to carry the town watchman on their shoulders to keep his feet from sullying the freshly fallen snow.

One does not speak of something as “Chelmizing” or “Chelmish” in American Jewish English, but one does do this in Yiddish, in which a khelemer mayseh, “a Chelmish incident,” can describe any case of seemingly rational principles being put to irrational use. The same is true of Israeli Hebrew, which has the common words ḥelma’i and ḥelma’ut, “Chelmish” and “Chelmism.” A recent article in the newspaper Ma’ariv, for instance, accused Israel’s health ministry of hitnahagut ḥelma’it, “Chelmish behavior,” in its approach toward quarantining arrivals at Ben-Gurion airport at the height of the COVID pandemic’s omicron wave. The ministry’s irrationality, the paper stated, lay in deciding to quarantine only those on flights from high omicron-incidence countries despite the obvious fact that a traveler from such a country could have gone from it to a lower-incidence one, boarded a flight for Israel there, and infected everyone on it.

Ma’ariv had a point. The ministry’s policy was the equivalent of the Chelmite who, asked why he was looking for a lost coin beneath a streetlamp rather than across the street where he had dropped it, answered, “Because I see better where there’s light.” As a state of being, Chelm is everywhere.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him yourself at [email protected].

More about: Chelm, History & Ideas, Poland, Ukraine