In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the ambitiously named Foundation for Religious Action in the Social and Civil Order. Its purpose: to “unite all believers in God in the struggle between the free world and atheistic Communism.” Writing about the conferences held by this foundation, Frances FitzGerald in her recent book The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America notes that among those giving “speeches on the spiritual factors in the anti-Communist struggle” were not only “Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish clergymen” but also “pious national-security officials such as Leo Strauss, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission.”

Leo Strauss? The University of Chicago political philosopher alleged by overheated critics of President George W. Bush to have been responsible for the Iraq war? No; here FitzGerald misspoke. But she can be forgiven: after all, even among Jews who pride themselves on their people’s contributions to American history, the name of Lewis Strauss (pronounced Straws, 1896-1974) is all but forgotten.

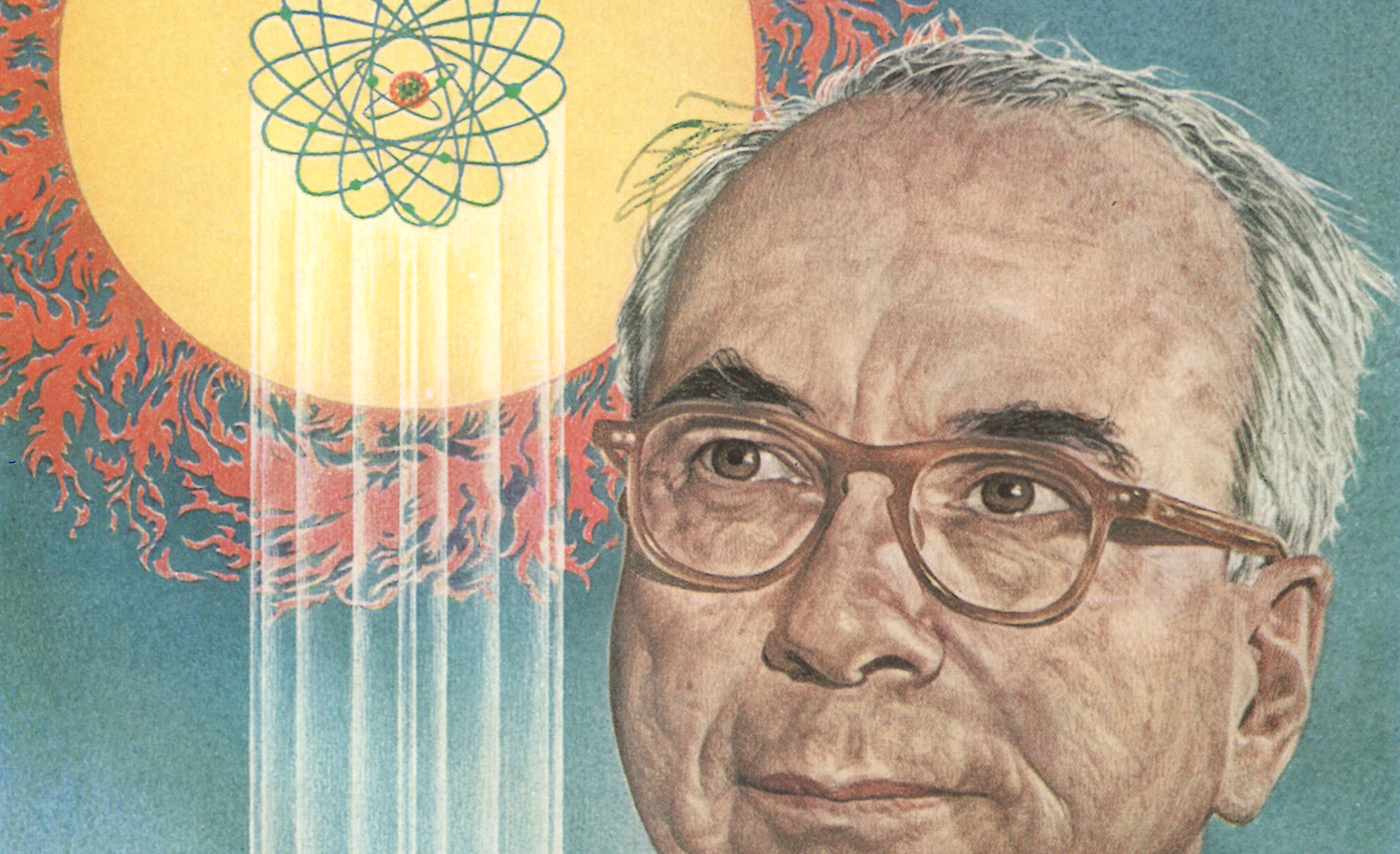

Which is a pity, since this Strauss was once a very well-known American official—in September 1953, his visage graced the cover of Time magazine—and certainly one of the most influential American Jews of the 20th century. He also happened to be both a political conservative and, for a great deal of his life, a determined anti-Zionist: two facts that might strike today’s reader as mutually exclusive and that make his story well worth knowing.

In what follows I mean to tell that story, focusing mainly on Strauss’s Jewish concerns with side excursions into his high government service and especially his key role in the development of atomic energy and nuclear weapons. In doing so, I’ll draw on his 1962 memoir, Men and Decisions (1962), Richard Pfau’s No Sacrifice Too Great; The Life of Lewis L. Strauss (1984), and, often more illuminating than either of these, the 75 boxes of his Jewish-related speeches, letters, and other writings held at the American Jewish Historical Society in New York. (The much more voluminous archives relating to his business and public career are housed in Iowa at the presidential library of Herbert Hoover, his lifelong friend.)

Lewis Strauss was born in 1896 in Charleston, West Virginia. His German-Jewish family was related neither to the “Our Crowd” German Jews, represented archetypically by such banking families as the Schiffs, Warburgs, and Loebs, nor to the Strauss who invented blue jeans—though his father, American-born, did become a fairly prosperous merchant in Richmond, Virginia, where young Lewis grew up. At home, he imbibed both his father’s deep attachment to the United States and the Republican party and his mother’s love for Reform Judaism. As a youth, very unusually for a Reform Jew at any time, he kept the Sabbath strictly, rigorously abstaining from all work.

Strauss would have attended the University of Virginia had not the recession of 1913-1914 dealt a severe blow to his father’s business. Instead, at the age of seventeen, he hit the road, selling shoes from West Virginia to Georgia. Despite his unwavering Sabbath observance and consequent weekly loss of a crucial business day, by 1917 he had saved the astonishing sum of $20,000, much more than enough to pay for his higher education. But 1917 was the year that American entered World War I, and men his age were being drafted en masse into the U.S. army. Disqualified on account of a severe eye injury from a schoolboy fight, he was nevertheless determined, somehow or other, to serve his country.

His mother pointed the way, calling his attention to a news report about a successful mining engineer turned relief organizer named Herbert Hoover, who had just been summoned to Washington to set up a new federal department managing the production and distribution of food. “Why don’t you go and help him?” she asked—which turned out to be a startlingly easy thing to do. Taking the train to Washington, the young man picked up a basically phony letter of recommendation from Virginia’s senior senator, waylaid Hoover at his hotel, and, after promising to work without pay, immediately landed a job.

Within a month, Strauss had proved himself so effectively that Hoover made him his private secretary. For the first time in his life, he also began to work on Saturdays, “a departure from religious observance that he justified,” according to Richard Pfau, “because of the emergency.” After the war ended in November 1918, he accompanied Hoover to Europe to organize a vast program to feed refugees and help restore the continent’s economy.

By then he had made his first, very fruitful contacts with bona-fide members of “Our Crowd.” Even before leaving for Europe he’d been approached by Felix Warburg, the powerful financier and philanthropist, with a plea to do what he could to help the desperate Jews of war-torn Poland. In Paris, Oscar Straus, the New York merchant who had been, under Theodore Roosevelt, the first Jewish cabinet officer in U.S. history, and who was now actively supporting the League of Nations, took him under his wing.

Strauss accomplished many good things in this period, in general through his work at the American Relief Administration (ARA) and in particular as a liaison between the ARA and the Joint Distribution Committee, which was working to relieve the sufferings of East European Jews. In the latter capacity, acting on an instinctive sense of solidarity with his people—a leitmotif, as we’ll see, of both his private and his public career—he was able to persuade Straus and Hoover to intervene to halt anti-Jewish discrimination and pogroms. In addition, his ties with Warburg and others led to a job offer from the firm of Kuhn, Loeb; in 1919, instead of finally enrolling in college, he headed to New York to make his fortune.

By 1922, Strauss had not only thrived in the world of finance but married the daughter of one of the firm’s partners, and by 1929 he’d become a partner himself. Now thoroughly ensconced as one of the more prosperous figures in “Our Crowd” society, he would also become one of its leaders. Among other positions, he would serve for many years on the executive board of the American Jewish Committee (AJC) and from 1938 to 1948 as president of Temple Emanu-El, the grand Reform citadel in New York.

Perhaps more surprisingly in view of his lifelong adherence to Reform Judaism, but less surprisingly in view of his instinct for Jewish fellowship, Strauss also served on the board, and as treasurer, of the Jewish Theological Seminary, the flagship institution of the Conservative movement. In the process he became a close friend and confidant of its chancellor Louis Finkelstein, a scholar of rabbinic Judaism who would be the principal speaker at Strauss’s funeral in 1974. The Strauss papers include a thick file of their correspondence over the decades, from birthday greetings to letters of condolence, from appeals for financial help to occasional discussions of Bible translation to—in one fascinating episode at the height of World War II, when Strauss was working for the Navy—an agonized exchange over the exclusion of Finkelstein’s college-age daughter, on the grounds of her Jewishness, from a special Navy-sponsored defense course in which she had enrolled.

During the 1930s, Strauss was especially zealous on behalf of German Jews fleeing Hitler and seeking refuge in America. In this endeavor, by his own anguished testimony, he proved only partially successful. The sixth chapter of his autobiographical memoir, entitled “De Profundis” and opening with the Psalmist’s words (“Out of the depths”) printed strikingly in the original Hebrew, gives a brief account of the Holocaust before turning to the prewar plight of German Jews. Strauss takes credit for the assistance he personally extended, as a representative of the AJC, to a significant number of refugees, but castigates himself for not having done “so much more than I did. I risked only what I thought I could afford. That was not the test which should have been applied, and it is my eternal regret.”

The same chapter also includes the memoir’s sole reference to his encounter with the Zionist movement: a meeting with Chaim Weizmann, the head of the World Zionist Organization, at a 1933 conference in London on the refugee problem. Strauss portrays Weizmann as a pragmatic man who was busy doling out legal permits to enter Palestine. Mistakenly assuming this process to have been entirely under Weizmann’s personal control, he reports feeling “bewilderment and indignation” when informed that the great Zionist was giving priority to “people who are Zionists but who are under no pressure of any sort [to flee]” over “poor souls who have no place to go.”

Unmentioned by Strauss is that, at this same conference, he himself undertook to oppose the Zionists by joining with others to block some of their proposals. When, according to Pfau, Weizmann made an effort to convert Strauss to the cause, intimating that he could make the American Jewish Committee “supreme in the United States,” Strauss refused to budge, provoking Weizmann to accuse him of being “difficult” and vow to grind him down.

If Weizmann ever made a move in that direction, it must have failed. For a long time thereafter, Strauss remained staunchly opposed to Zionism, joining the American Council for Judaism, an explicitly and fervently anti-Zionist organization, soon after its founding in 1943. His papers include innumerable missives from the Council’s leader, Elmer Berger, deriding Zionism in the harshest terms, along with other anti-Zionist literature and thank-you notes for his generous contributions to the Council’s activities.

On these subjects, it seems, Strauss listened more than he talked. An exception, included in his papers at the American Jewish Historical Society, is the handwritten text of an address delivered to a Council chapter in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. This was on November 19, 1947, at the very moment, ten days before the UN’s partition vote, when the creation of the state of Israel hung in the balance. In the address, Strauss outspokenly disavowed the ideas of “Jewish nationalism and statehood” and counted himself among those who “are Jews as a matter of religious inheritance, as a matter of faith and conviction—and only that.”

Nor was that all. The “aim to establish a Jewish state,” Strauss said, “is not a new phenomenon among our people. Its repeated attempts have brought catastrophe and misfortune.” Retelling the biblical story of the prophet Samuel’s resistance to the people’s plea for a king, Strauss attributed the Israelites’ misguided demands to a dream of “grand-scale assimilation” to the ways of others that would ultimately lead to their own “captivity and exile.” Yet even then, he wrote, the Jews stubbornly refused to grasp their “real mission” on earth—to introduce and spread ethical monotheism—and might not ever grasp it until their “obsession with temporal dominion and reliance upon human sovereignty shall have been eliminated or forsworn.”

Of one thing Strauss remained certain: “salvation will not come out of a Zion rebuilt upon violence, cold-blooded murder, and brutality”—he was alluding to recent actions by the violently anti-British Irgun and Stern Gang—and still less from a Zion rebuilt by secularists. While the new Jewish colonies in Palestine were (he thought) devoid of synagogues,

[w]e continue to be Jews because we are witnesses to the principal discovery made by man—a discovery which dwarfs the greatest findings of modern giants of science—the discovery of the fact of the oneness of the Creator and all that has grown out of that revelation.

Not Zionism, then, but monotheism: this became the theme of almost all of Strauss’s frequent orations on the Jewish mission and the Jewish future, whether addressed to Reform or Conservative assemblages or, in later years, to radio audiences.

In brief, Frances FitzGerald may have gotten Lewis Strauss’s name wrong, but she was right to call him a “pious official.” To his life as an official we may now briefly turn.

Strauss held a commission in the Naval Reserve from 1925 onward. In the late 30s, alarmed by the country’s lack of preparedness for war, he volunteered several times for active duty. In March 1941, having been taken up on his offer, he went to Washington to work for the Navy Department. There, in the area of procurement, he made valuable contributions to what soon became the war effort. By 1945, he held the position of rear admiral and special assistant to Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal.

At war’s end he intended to return to Kuhn, Loeb but couldn’t resist an appointment to the newly created Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). With the backing of Navy leaders like Admiral Paul Foster—who averred that Strauss was “nationally known as a conservative, pro-American leader in the Jewish religion”—and important aides to now-President Truman like Clark Clifford and the longtime FDR adviser Sam Rosenman, he was selected as one of the AEC’s six original members. The position required him to sever all business relationships, which meant the end of his partnership in Kuhn, Loeb. He served on the commission from 1946 to 1950 and then, after a hiatus, as its chairman between 1954 and 1958.

The story of Strauss and atomic energy, nuclear scientists, and nuclear weapons is a long one, taking up roughly half of his autobiography and more than half of Pfau’s No Sacrifice is Too Great. Among many other incidents, both books relate the crucial behind-the-scenes debate in 1949 and 1950 over the development of a hydrogen bomb (then called a “superbomb”). A General Advisory Committee, designated by Congress with the responsibility of overseeing the AEC, had concluded unanimously that the U.S. should refrain; its final report, drafted by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the former scientific director of the Manhattan Project, predicted that “the use of this weapon would bring about the destruction of innumerable human lives” and expressed the “hope that by one means or another the development of these weapons can be avoided.”

For his part, Strauss held the contrary, finding it reasonable to assume that the Soviets not only could but would develop a superbomb and concluding that the United States should follow suit lest the USSR achieve a dangerous monopoly. Having himself originally opposed the project, he now firmly believed that any decision to refrain would not be reciprocated. As he wrote to President Truman, “a government of atheists [i.e., the USSR] is not likely to be dissuaded from producing the weapons on ‘moral’ grounds.”

In November 1949, the commission voted 4-1 in favor of the project. “Although others helped move the process of decision,” Pfau writes, “Strauss was the first and most persistent advocate.” In short order, “the president ordered [the program] forward.”

Strauss’s argument was advanced on strategic grounds, but his distrust of Oppenheimer was enhanced by what he read in the AEC’s security file on the scientist, which detailed Oppenheimer’s left-wing activism and association with Communists while teaching at Berkeley in the 30s. Later, when Strauss rejoined the AEC and became its chairman at the behest of President Eisenhower, he pressed for the removal of Oppenheimer’s security clearance, a goal he achieved in 1954. This not only earned him notoriety at the time but decades later would ensure his role as one of the principal villains in Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2006).

The confrontation with Oppenheimer may have been the episode in Strauss’s political career that has left the biggest imprint on the historical narrative, but it by no means marked the end of his involvement in highly consequential national affairs. As chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, he fought successfully for the continuation of atomic-weapons tests and for the commercial use of nuclear power. When his term of office expired in 1958, President Eisenhower, who had just awarded him the Medal of Freedom, asked him first to replace Sherman Adams as “assistant to the president” and then, when Strauss demurred, to succeed John Foster Dulles, then dying of cancer, as Secretary of State. Strauss again declined, but was willing to replace the departing Secretary of Commerce since that department, in his view, was the place where “the economic warfare which the Soviet government has declared upon the United States can be most effectively countered.”

Through a recess appointment made on November 13,1958, Strauss became the first and only Jew to serve in Eisenhower’s cabinet, and the only Jew in the interval between the Roosevelt and Kennedy administrations to be appointed to a cabinet office. He wasn’t there for long, however. In January 1959, Eisenhower sent his nomination to be confirmed by the Senate, now led by Democrats; there, after a prolonged public debate, it was voted down—no doubt in part because of the Oppenheimer controversy.

This defeat marked the end of Strauss’s public career, but hardly his role in Jewish life—where matters would take a turn of a different kind.

Although for years Strauss remained a member and a financial backer of the American Council for Judaism, his hostility to Zionism was not altogether unremitting. There is only one mention of the state of Israel in Men and Decisions, but Pfau notes that Strauss came to terms with Israel’s existence after its creation. As President Eisenhower’s adviser for Atoms for Peace, “he recommended a solution for the Arab-Israeli dilemma built around the use of atomic power to operate desalinization plants around the eastern shore of the Mediterranean,” a project he touted till the end of his life.

More pointedly, at a meeting of the National Security Council at which he was present, Strauss responded to a caustic comment by Secretary of State Dulles referring to Israel as “the darling of world Jewry.” There were “a very great many Americans of Jewish faith like myself,” Strauss said, “who took a dim view of the establishment of the state of Israel”—but the creation of a Jewish state had “resulted in saving the lives of perhaps as many as two million innocent men, women, and children—the remnant from the gas chambers and massacres of Hitler and his imitators.”

By the time of his 1962 autobiography, Strauss was still ambivalent about Zionism, but in a different way. Recollecting his 1933 encounter with Weizmann, he was more forgiving of the latter’s pragmatism; Weizmann’s movement had, after all, saved untold numbers of lives. Still, hedging his bet, Strauss observed that “the wisdom of [the Zionist] course will be determined only long after this is written.”

Two years later, his ground-note Jewish solidarity stirring into life, Strauss finally traveled to Israel. There, Pfau reports, “he felt deeply in touch with his people’s early history.” He was particularly struck by the story of the Jewish zealots who had held out against the Roman besiegers at Masada and in the end took their own lives rather than surrender. Whether or not he made it to the top of Masada—no easy climb for a man of his age—he did talk to Yigael Yadin, the great soldier-archaeologist of its ruins, and in 1967 published an article on the site and Yadin’s work, describing him with unfeigned enthusiasm.

So far as I’ve been able to determine, Strauss’s papers contain no correspondence dating from the fateful weeks before the Six-Day War of June 1967. But in prepared remarks at a farewell dinner in January 1968 for the outgoing Israeli ambassador to the United States, Avraham Harman, and his wife Zena, he said the following:

Some of us who are here tonight were dinner guests at the Israeli embassy in the final days of last May [1967], . . . and many of us, the Harmans’ guests, feared the little nation they represented would be swept into the sea and obliterated as their enemies had so repeatedly predicted. . . .

Finally the time came for saying our goodbyes and we remembered that the Harmans had a son in the Israeli army—so soon perhaps to be overrun by superior numbers. Our hearts were heavy for them that evening. Now all that and the miraculously short war itself only eight months ago seems already to be a part of ancient history.

A few months later, he drafted remarks for an upcoming baccalaureate service of the West Point Jewish Chapel Squad, where he planned to inspire the cadets with thoughts of the noble pedigree connecting past Jewish heroes with contemporary Israeli military figures and thus, by inference, themselves:

From that remote day 4,500 years ago, when Abraham successfully led his band of “trained young men” against the federated city kings to the rescue of his brother Lot, the roll of commanders of fighting men is a long and heroic one—Joshua, Gideon, Jephtha, David, Joab, Abner, the Maccabees, Ben Yair, the defender of Masada, whom archaeology has restored to history only recently (after 2,000 years) to name but a few of them—and on down to Generals [Moshe] Dayan and [Yitzhak] Rabin in our own generation.

Nor was that all. In these same draft remarks, Strauss also took care to single out David “Mickey” Marcus, West Point class of 1924, who had died fighting with the Israeli army in 1948 and whose grave one would pass before entering the chapel. Strauss compared him with Stonewall Jackson, another hero killed accidentally by a sentry’s bullet, and then quickly summarized Marcus’s career in words that married Zionism with Americanism:

And while Marcus, following distinguished service in the Second World War, had volunteered to help a new nation achieve its independence, he was animated by the same love of freedom which motivated Lafayette, von Steuben, Pulaski, and other allies who offered their swords to General Washington in our war of independence.

In sum, it’s no coincidence that in these years Strauss was slipping away from the American Council for Judaism. On October 9, 1967, Elmer Berger wrote to him as one of “approximately 50 Council members” from whom he was seeking urgent financial help. “The turbulent events in May-June,” Berger wrote, referring to Israel’s smashing victory four months earlier, had created new opportunities as well as new dangers:

With all the sincerity I can command I ask your most sober and generous consideration of these requests [for funds]. It can be said, categorically, that your response will determine whether, or not, there will be effective alternatives for American Jews to the greatly increased entrenchment of Zionist nationality which was one byproduct of the Middle East crisis.

Too late. Although it’s not possible to pinpoint the exact moment of Strauss’s transformation from stalwart anti-Zionist into ardent friend of Israel, there’s no great mystery here. Strauss’s theology may always have been that of classical Reform with its insistence that Judaism was a religion, not a nationality. But from his days in the American Relief Administration through the 1930s and beyond, his eager efforts to help Jews in need were not mere philanthropy; nor was the Jewish martial resolve he admired at Masada and in contemporary Israel mere bluster. All reflected the selfsame deeply felt solidarity, and the need to act on it.

In No Sacrifice Too Great, Pfau reprints a poem written by Strauss at the age of twenty-three. It includes these lines:

The blood of Maccabees runs in my veins

And courses hot past throbbing temples

Calling me to rise

And smite the foes of God and Righteousness.

That a man who had been imbued with such feelings from an early age would ultimately prove receptive to the Zionist message seems almost inevitable.

More about: American Judaism, EIsenhower, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism