Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

In your preparations for Father’s Day on Sunday, June 17, you may have overlooked Bloomsday the day before. If you did, I submit that you missed the more important event. Fathers come and go. There will always, however, be only one Leopold Bloom, whose life and thoughts on June 16, 1904, along with those of his wife Molly and of Stephen Dedalus, the autobiographical hero of James Joyce’s first novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, are the subjects of Joyce’s second novel Ulysses (1922). Observed annually since 1924, Bloomsday is marked by some lovers of Ulysses by carousing in the pubs of Dublin, the city in which it takes place. Others prefer to settle with it into an armchair at home. It was while performing the latter ritual this month that I was led to consider the case of Agendath Netaim.

The reader first encounters these words in the second chapter of Ulysses. There, the half-Jewish Leopold Bloom is on his way home from a non-kosher Jewish butcher in whose shop he has bought pork kidneys for his breakfast while picking up a loose page from a stack of papers on the counter used to wrap meat in. The page comes from an illustrated Zionist advertising prospectus, and Bloom “walked back along Dorset Street, reading gravely. Agendath Netaim: planters’ company.” As he walks, he ponders what he reads:

To purchase vast sandy tracts from Turkish government and plant with eucalyptus trees. Excellent for shade, fuel, and construction. Orangegroves and immense melonfields north of Jaffa. You pay eight marks and they plant a dunam of land for you with olives, oranges, almonds, or citrons. . . . Your name entered as owner in the book of the union. Can pay ten down and the balance in yearly installments. Bleibtreustrasse 34, Berlin, W.15.

As any reader with some Hebrew would know, Agendath Netaim is a garbled form of Agudath (or Agudat) Netaim, agudat being the possessive of agudah, a society or association, and n’ta’im meaning “plantations” (not, as Ulysses has it, “planters”). Few such readers, though, are likely to know that an organization named Agudat Netaim actually existed.

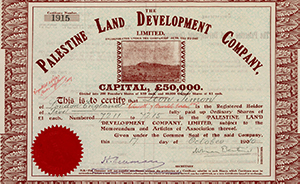

Founded in 1905, a few months after the date of Bloom’s fictional encounter with it (Joyce wrote Ulysses between 1904 and 1914 and was apparently unaware of this anachronism), Agudat Netaim was established as a joint stock company for the purchase of land in Ottoman-ruled Palestine and its resale to prospective Jewish farmers. Although registered in Constantinople, its administrative headquarters were in Berlin. One thing I learned from my research this past Bloomsday was that its location at 34 Bleibtreustrasse (“Staytrue Street”) was not, as I had always assumed, a humorous invention on Joyce’s part in allusion to the Jewish people’s historical allegiance to Palestine. Rather, it was the stock company’s actual address in the fashionable district of Charlottenburg, near the famed Kurfürstendamm, on a street named for the German artist Georg Bleibtreu.

Bloom finishes reading the torn-out page, folds it, and sticks it in his pocket. But though it remains there untouched, the words Agendath and Netaim, whether singularly or together, keep crossing his mind in the course of the day; altogether, they recur a dozen times in the novel. The leitmotif sounded by them has various components: a curiosity about Zionism; a vague attachment to a Jewish heritage Bloom knows nothing about; a yearning for a homeland in which he is not made to feel an outsider as he is in Ireland; an attraction to exotic places and things, which he associates with his Gibraltar-born wife; a fantasy of wealth acquired by investing in Palestinian real estate.

And yet all of this has its reverse side. Bloom thinks he knows enough about history and geography to understand that the Jewish dream of Palestine—his dream, at moments of this day—may be a fatal atavism that will drag its dreamers down with it. No sooner has he turned into Eccles Street, on which he lives, than he reflects:

No, not like that. A barren land, bare waste. Volcanic lake, the dead sea: no fish, weedless, sunk deep in the earth. . . . A dead sea in a dead land, gray and old. Old now. It bore the oldest, the first race.

Seeing an old woman, a “bent hag,” cross the street in front of him, he continues to muse:

The oldest people. Wandered far away over all the earth, captivity to captivity, multiplying, dying, being born everywhere. It [Palestine] lay there now. Now it could bear no more. Dead: an old woman’s: the grey sunken c—t of the world.

Desolation!

The associations aroused by Agendath Netaim seesaw in Bloom’s mind throughout the day until finally, at home that night, he uses the page of the prospectus to light a cone of incense. In a chapter in which everyday acts are comically described with an exaggerated precision, we read how he

placed [a] candlestick on the right corner of the mantelpiece, produced from his waistcoat a folded page of prospectus (illustrated) entitled Agendath Netaim, unfolded the same, examined it superficially, rolled it into a thin cylinder, ignited it in the candle flame, applied it when ignited to the apex of the cone till the latter reached the stage of rutilance, [and] placed the cylinder in the basin of the candlestick, disposing its unconsumed part in such a manner as to facilitate total combustion.

Is this, as some critics have contended, a symbolic rejection of Zionism by Bloom—and by extension, by Joyce? Not necessarily. “What followed this operation?,” the text next inquires (the entire chapter being written in question-and-answer form), to which it replies: “That truncated conical crater summit of the diminutive volcano emitted a vertical and serpentine fume redolent of aromatic oriental incense.”

Are we being told, then, that the volcanic (it isn’t really volcanic, but no matter), evil-smelling lake of the Dead Sea, the “gray sunken c—t of the world,” is (at least for Bloom) still alive and potentially fragrant?

Let the Joyce experts argue. I’ll stay out of it. I will, though, join the speculation about why the Agudat of Agudat Netaim was turned into Agendath. Five different explanations have been offered:

(1) The prospectus or the page of it seen by Joyce, who knew no Hebrew, had a typographical error that he copied.

(2) The error was not in the prospectus but in the copy Joyce made of it.

(3) Joyce copied the prospectus correctly but later, when using it for Ulysses, misread what he had written.

(4) The handwritten manuscript of Ulysses submitted by Joyce to the printer had Agudat Netaim written correctly, and the error was the printer’s.

(5) There was no error. Joyce, an inveterate player on words, changed Agudath to Agendath deliberately. He may have been punning on Agenda, on Uganda (offered to Herzl by the British in 1903 as an alternative site for a Jewish state), or on something else.

The first explanation seems to me unlikely. No known copy of an Agudath Netaim prospectus contains such a mistake, and prospectuses are legal documents that no stock company would issue without careful proofreading.

The fourth explanation is equally improbable. A printer may have misread Joyce’s manuscript in one place, but in a dozen? Moreover, Joyce proofread the first edition of Ulysses himself. Surely, he would have caught a misprint that was repeated a dozen times.

The fifth explanation, too, makes little sense. Joyce did love puns, but he was also deeply committed to the factual accuracy of the background material in Ulysses. And what would punning on Agenda or Uganda have contributed to the novel? Nothing at all—and if there is anything that Joyce critics agree on, it is that he never wrote anything without a reason.

That leaves explanations (2) and (3). Both are plausible. If forced to choose between them, however, I would favor (3). Whereas u’s and n’s don’t look the same in print, their peaks and valleys are easily confused in script (try quickly writing “ununified” and you’ll see what I mean), and the tail on the “g” of Agudath, after looping back and over the letter’s downward line, could be interpreted as a tiny “e” if the character after it were mistaken for an “n.” Photographs of Joyce’s handwriting show that such a mistake on his part would have been quite possible.

If so, there are no hidden agendas in the “Agendath” of Ulysses. If the error wasn’t corrected after the book’s first edition in 1922, this was probably because none of its early readers knew any more Hebrew than did Joyce himself—and by the time it was discovered, it was part of the text of one of the English language’s greatest novels and could no longer be changed without protest. One doesn’t tamper with sacred writ. And for the celebrants of Bloomsday, that’s practically what Ulysses is.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Aliyah, Arts & Culture, Israel & Zionism, James Joyce, Literature