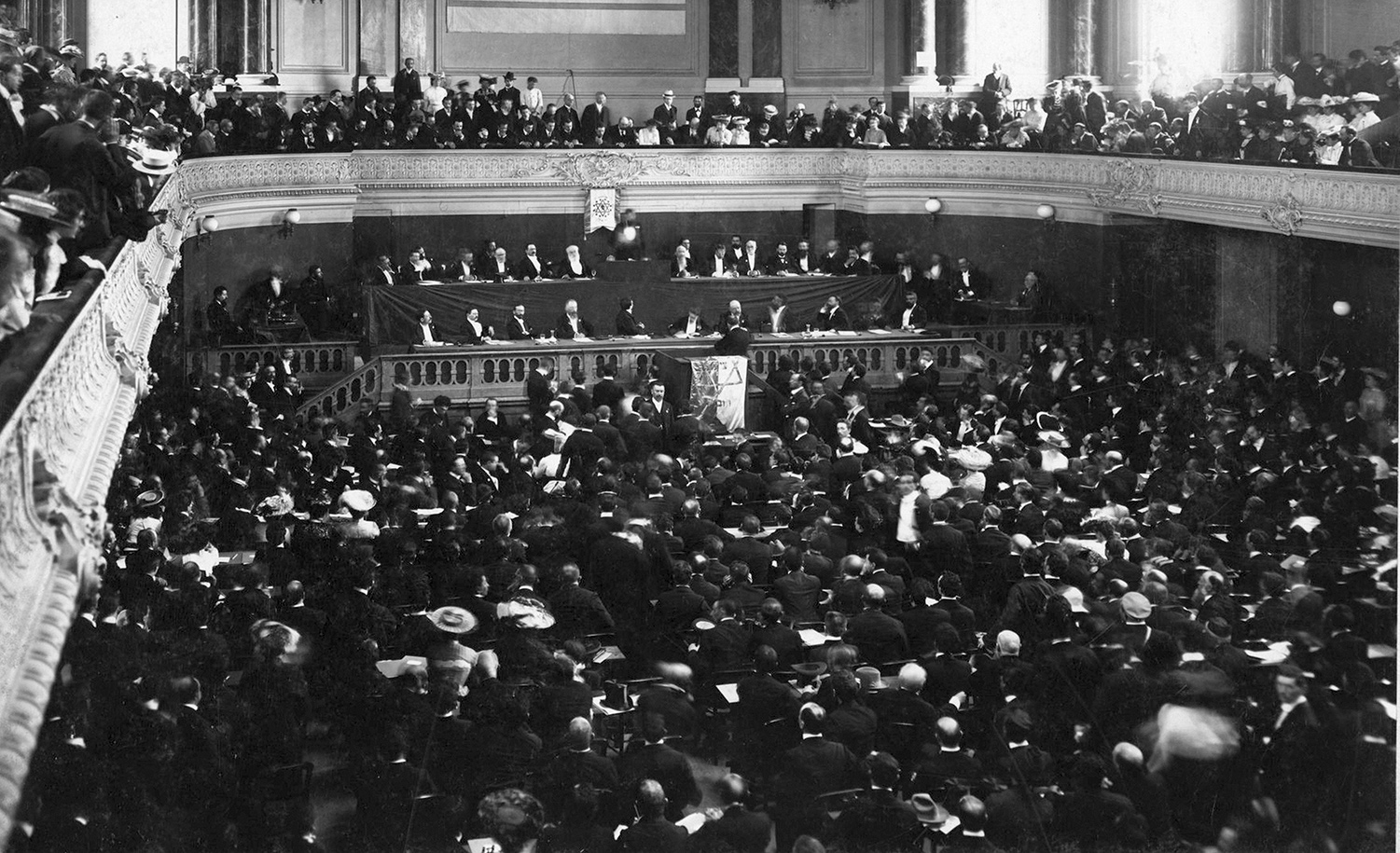

The First Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897. Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

August 1897 was one of the most thrilling months in modern Jewish history.

Only a year-and-a-half earlier, when he published The Jewish State, Theodor Herzl might have struck his friends and colleagues as a person of unsound mind. But on August 29, 1897—122 years ago tomorrow—a couple of hundred delegates from all over the world showed up in Basel, Switzerland to attend the Zionist Congress that Herzl had conjured up out of next to nothing. At that moment, it was clear to all that he was a man to be taken seriously.

It is still clear, if not clearer than ever in hindsight. At that perilous juncture in Jewish history, replete with bigotry, persecutions, pogroms, and the travails of mass resettlement, the proud assemblage in Basel stands out as an event of great and unprecedented promise.

Many historians of Zionism and biographers of Herzl and the other notables in attendance have done full justice to the event, describing the great care Herzl took to lend dignity to the proceedings and the magical impact of his first appearance in the transformed concert hall of a Swiss casino to the cry y’ḥi ha-melekh! (“long live the king”!) on the part of people who, all at once, no longer felt themselves to be utterly downtrodden.

And Herzl did not disappoint. Proceeding to deliver a masterful speech, he summarized the problems faced by the world’s Jews, identified the solution to them, and circumspectly formulated the self-imposed limits to his vision. “Zionism,” above all, he said,

means a returning home to Jewish identity before the return to the country of the Jews. We sons who have returned home find many things in the ancestral home that cry out for improvement; in particular, we have brothers [there] steeped in misery. Yet we have been welcomed in the ancient house because, as is known to all, we do not presume the right to subvert cherished institutions. This will become plain with the development of the Zionist program.

Herzl’s principal collaborator, the celebrated writer Max Nordau, followed with a speech that Herzl considered superior to his own and that again focused less on the material than on the spiritual plight of contemporary Jews. In particular, Nordau had in mind those Western Jews who remained unwelcome even in the European countries that had emancipated them and expanded their opportunities:

The Jew of the West has bread, but man does not live on bread alone. The Jew of the West is scarcely ever put in jeopardy of life and limb by mob hatred, but wounds of the flesh are not the only ones that cause pain and from which one may bleed to death.

The resurgence of anti-Semitism in the lands of the Enlightenment, said Nordau, had left the Western Jew feeling

that the world is hostile toward him, and while seeking and yearning for emotional warmth, he sees no place in which to find it. This is the moral deprivation of Jews, which is more bitter than the physical, because it afflicts persons who are more sophisticated, prouder, and more sensitive.

According to the London Jewish Chronicle, Nordau’s speech was repeatedly interrupted by loud expressions of assent, and evoked many tears.

When Nordau finished, Oscar Marmorek, an Austrian-Jewish architect and another of Herzl’s closest collaborators, took the podium to offer praise for both leaders’ inaugural addresses. “We will never be able to forget what we have heard as long as we live,” he said, proposing the immediate release of Herzl’s and Nordau’s speeches in a separate publication. Herzl, however, advised against this, noting the plans already in place to release the complete stenographic proceedings of the Congress; but when he allowed the matter to come to a vote, the delegates unanimously disagreed with him.

In the ensuing century-plus, Herzl’s and Nordau’s opening orations have continued to outshine everything else that was said during the next two days in Basel. But, until now, the English-speaking reader has had little direct access to the bulk of the Congress’s deliberations, which were conducted in German. Thanks, however, to the historian Michael J. Reimer, we now have at our disposal a full translation of the stenographic record, together with a judicious introduction and summary of the proceedings as well as extensive and very helpful scholarly notes. I’ll make use of these resources to relate, briefly, some highlights from the rest of the story of the Congress.

After the delegates voted Herzl down and authorized the separate publication of his and Nordau’s speeches, representatives from a number of different countries reported on the overall situation of the Jews in Galicia, Great Britain, Algeria, Romania, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria. These presentations were long, very detailed, and often less than edifying. One can easily imagine delegates slipping quietly out of any one of them or, in the afternoon session, falling asleep as Professor Gregor Belkovsky explained how in Bulgaria “the Karavelovists are worse anti-Semites than the Tsankovists.”

Interestingly, the speaker following Belkovsky, a lawyer from New York named Adam Rosenberg, gave a presentation less than one-seventh as long and with much less to complain about. “To be sure,” he admitted, “there is in America also a kind of anti-Semitism. But it is only a fashion imported by foreign immigration elements.” This, alas, was an exaggeration. More or less correct, by contrast, was Rosenberg’s assessment of the fortunes of the Zionist movement in the U.S.: “in general,” he informed the Congress, “Zionism in America nowadays is spread only among the Russian immigrants who have sought their fortune there but have not found it.”

But then came what by all odds was the most notable speech of the Congress’s first afternoon or even, some might say, the entire first day. It was delivered by Dr. Nathan Birnbaum, who probably felt that he ought to have spoken in the morning right after Nordau, if not in place of him.

Birnbaum was a veteran Zionist who had been on the scene long before either Nordau or even Herzl had had a glimmer of an idea of the Jews’ return to the Land of Israel. It was he, in fact, who five years earlier had coined the term “Zionism.” His relationship with Herzl, who would no doubt have been happier had he not come to Basel at all, was deeply fraught. But he was a man who could not be overlooked.

In his speech, Birnbaum’s principal concern was the lamentable dearth of Jewish cultural originality. Even in Eastern Europe, he declared, where admittedly things were stirring, “No steps of cultural progress are occurring, only a stepping-out of native culture and into European civilization.” For the Jews to develop “a normal, progressive, national cultural life,” they would need a home of their own in their ancestral land. Moreover, Birnbaum added, expanding his vision dramatically,

a Jewish people possessing a sovereign state, established in Palestine, will not only be, inwardly, the intermediary between the social-ethical and the political-aesthetic principles in Europeanism, but will also be, outwardly, the long-sought mediator between Orient and Occident.

Birnbaum’s explicit reference to a sovereign Jewish state was the first on the floor of the Congress. It must have irritated Herzl, whose foray into the Ottoman empire after publication of The Jewish State had taught him how necessary it was for the Zionists to downplay their ultimate goal. Nor was Birnbaum himself unaware of the difficulties involved in achieving sovereignty, and he proceeded to elucidate one of the principal ones.

People doubt, he said, that the Zionists would “be able to endure the competition of other, older, and stronger cultures aspiring to control Palestine.” But he insisted that “the situation is not as bad as all that. If it were, then many small nation-states would not have arisen in the last several decades.” Here, as Reimer usefully notes, Birnbaum was referring “to the several Balkan states which gained autonomy or independence in the latter part of the 19th century: Montenegro, Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria.”

Birnbaum was, in fact, not only the first but the only speaker at the first Zionist Congress to call for Jewish sovereignty over Palestine. Ironically, and bizarrely, his own days in the Zionist movement were numbered, as he was soon to morph into a Diaspora nationalist and then, after World War I, into an ultra-Orthodox anti-Zionist. Yet all that lay in the future. In August 1897 Birnbaum was, in a sense, the most Zionist of the Zionists.

Indeed, what Birnbaum called for in Basel was above and beyond what Max Nordau would put forward to the Congress the next morning: a committee-designed first draft of what was to become known as the Basel Program. In its very first sentence, the draft announced that “Zionism strives to create a homeland in Palestine for the Jewish people secured by law” (einer rechtlich gesichterten Heimstätte). This was, in Nordau’s words, “fair to the passionate and the prudent, the militant and the fainthearted,” and he urged its passage without debate.

For some delegates, however, even if they didn’t want to put things as directly as Birnbaum, this was not enough. Fabius Schach, from Cologne, insisted that “without international guarantees our national home can never gain security” (emphasis added). The “gathering point for a resurrected Jewish people,” Shach stressed, “has to be endowed with international legality (völkerrechtlich)!” Leo Motzkin, from Kiev, chimed in, noting that both Leo Pinsker, in his pioneering treatise Autoemancipation (1882), and Herzl himself in The Jewish State had employed similar language, and that it is “important for our solidarity, for the solidarity of the whole Jewish people, that our ideal be articulated clearly.”

Herzl, for his part, was flexible on the matter but only up to a point. He proposed the addition of a single word to the draft, changing rechtlich (legal) to öffentlich-rechtlich (public-legal). This compromise won the day, or rather the morning, pushing a small step beyond the merely legal without clearly drawing anyone other than the Turks into the picture.

Shortly after the vote approving the draft, Max Bodenheimer, one of Herzl’s key associates, gave voice to his own concern about alarming the Turks. Without naming Birnbaum at all, but wanting to be sure the sultan would “not be threatened by our aspirations,” he pointedly remarked that

[t]he Jewish people gratefully acknowledges the tolerance which the Turkish sultans have always practiced toward the Jews, and will never forget that they opened their empire in hospitality to them at the time of the Spanish Inquisition. We, too, have the earnest intention of reaching, by means of our organization, an international agreement on the basis of common interests, without impairing the sovereignty of the sultan in any way.

In thus speaking of the need for an “international agreement,” Bodenheimer, as Reimer observes, was still lobbying for “the wording he himself had submitted to the committee that drafted the [Basel] Program” even after that wording had been rejected in favor of Herzl’s compromise.

The clearest response to Nathan Birnbaum was that of Jacob Bernstein-Kohan, a Russian veteran of the proto-Zionist movement known as Lovers of Zion, who on the afternoon of the second day of the Congress called explicitly for the establishment of an autonomous Jewish state under Turkish suzerainty. “We must not deceive ourselves,” he said, before proceeding to deflect the connection that Birnbaum had sought to draw with other emerging nation-states:

The struggle . . . which several peoples of the Balkan Peninsula have fought to a successful conclusion was much easier than ours, since the peoples in question lived on their own soil, while in Palestine there are few Jews and little Jewish cultural life. Furthermore, the powers and the peoples subject to them are accustomed to thinking about solving the Jewish question in an entirely different manner, and it may be quite hard for us to guide their thoughts in an unaccustomed direction and to interest them in a cause in which the bulk of Jewry itself shows far too little interest. Therefore, the question of political independence in Palestine seems not to be a question for the immediate future.

Herzl must have liked hearing these last words, even if he would have preferred not to have had this highly sensitive subject discussed at all on the floor of the Congress.

In the end, however, what was said on the floor was of less importance to Herzl than the simple fact that the floor was there at all. The delegates’ job, as far as he was concerned, wasn’t to clarify the ultimate goal of Zionism so much as to get the ball rolling simply by being there and thus testifying to the Turks and to the world in general that he was by no means alone, that he had many people behind him and was therefore not just a single visionary but a force to be reckoned with.

It would be easy to say that he failed at this. After all, when he died on July 3, 1904, after five more congresses and a much larger number of futile diplomatic initiatives, he was no closer to realizing the goal spelled out (however cautiously) at the beginning of the Basel Program than he had been in August 1897.

But Herzl himself knew better. As he wrote in his diary a few days after the first Congress ended,

At Basel I founded the Jewish state. If I said this out loud today, I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it.

Of course, as has often been noted, this prophecy was off—by almost an entire year.