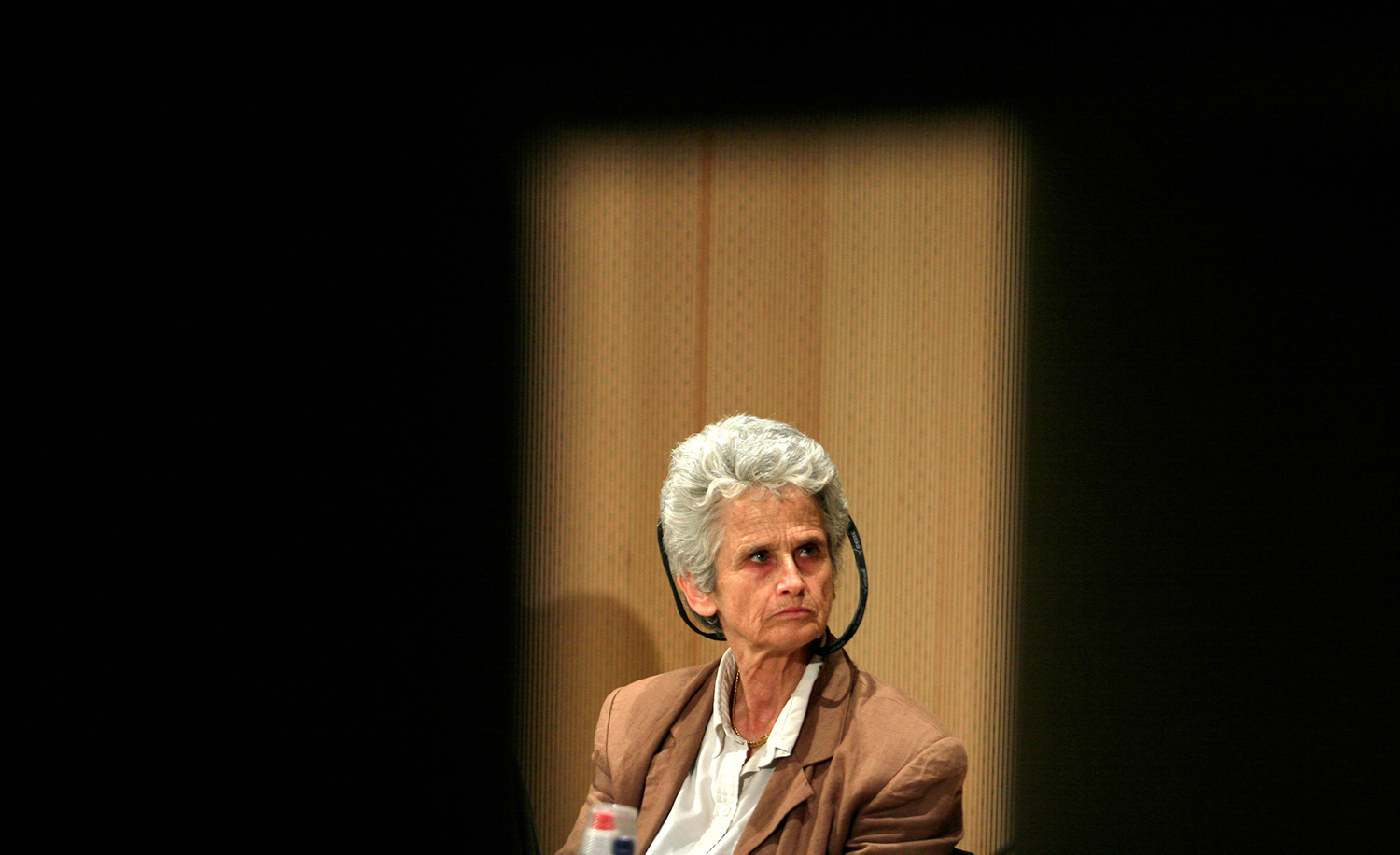

This essay by the renowned Israeli legal theorist Ruth Gavison was originally published in the Israeli journal Azure in 2003. We are republishing it August 18, 2020 in the wake of her death on August 15.

I.

Is it possible to justify the existence of a Jewish state? This question, raised with increased frequency in recent years, is not just a theoretical one. Israel will endure as a Jewish state only if it can be defended, in both the physical and the moral sense. Of course, states may survive in the short term through sheer habit or the application of brute force, even when their legitimacy has been severely undermined. In the long run, however, only a state whose existence is justified by its citizens can hope to endure. The ability to provide a clear rationale for a Jewish state is, therefore, of vital importance to Israel’s long-term survival.1

Over the many years in which I have participated in debates about Israel’s constitutional foundations and the rights of its citizens, I did not generally feel this question to be particularly urgent. Indeed, I believed that there was no more need to demonstrate the legitimacy of a Jewish state than there was for any other nation state, and I did not take claims to the contrary very seriously. Those who denied the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish state were, in my eyes, little different from the radical ideologues who dismiss all national movements as inherently immoral, or who insist that Judaism is solely a religion with no right to national self-expression; their claims seemed marginal and unworthy of systematic refutation.2

Today I realize that my view was wrong. The repudiation of Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state is now a commonly held position, and one that is increasingly seen as legitimate. Among Israeli Arabs, for example, it is nearly impossible to find anyone willing to endorse, at least publicly, the right of Jews to national self-determination in the Land of Israel. Rejection of the Jewish state has in fact become the norm among most representatives of the Arab public—including those who have sworn allegiance as members of Knesset. As far as they are concerned, the state of Israel, inasmuch as it is a Jewish state, was born in sin and continues to live in sin. Such a state is inherently undemocratic and incapable of protecting human rights. Only when it has lost its distinctive Jewish character, they insist, will Israel’s existence be justified.

More worrisome, perhaps, is the fact that many Jews in Israel agree with this view, or at least show a measure of sympathy for it. Some of the Jews committed to promoting the causes of democracy, human rights, and universal norms are, knowingly or not, assisting efforts to turn Israel into a neutral, liberal state—a “state of all its citizens,” as it is commonly called. Few of them understand the broader implications of such a belief for Israel’s character. Most are simply reassured by Israel’s success in establishing a modern, secular, liberal-democratic state with a Jewish national language and public culture, and think these achievements are not dependent on Israel’s status as the nation state of the Jews. Like many liberals in the modern era, they are suspicious of nation states, without always understanding their historical roots or the profound societal functions they serve. This suspicion often translates into a willingness to sacrifice Israel’s distinct national identity—even when this sacrifice is demanded on behalf of a competing national movement.3

Nor, at times, have Israel’s own actions made the job of justifying its unique national character an easy one. On the one hand, the government uses the state’s Jewish identity to justify wrongs it perpetrates on others; on the other, it hesitates to take steps that are vital to preserving the country’s national character. The use of Jewish identity as a shield to deflect claims concerning unjustifiable policies—such as discrimination against non-Jews or the Orthodox monopoly over matters of personal status—only reinforces the tendency of many Israelis to ignore the legitimate existential needs of the Jewish state, such as the preservation of a Jewish majority within its borders and the development of a vibrant Jewish cultural life.

It is against this backdrop that I write this essay. In what follows, I will argue that the idea of a Jewish nation state is justified, and that the existence of such a state is an important condition for the security of its Jewish citizens and the continuation of Jewish civilization. The establishment of Israel as a Jewish state was justified at the time of independence half a century ago, and its preservation continues to be justified today. Israel does have an obligation to protect the rights of all its citizens, to treat them fairly and with respect, and to provide equally for the security and welfare of its non-Jewish minorities. Yet these demands do not require a negation of the state’s Jewish character. Nor does that character pose an inherent threat to the state’s democratic nature: on the contrary, it is the duty of every democracy to reflect the basic preferences of the majority, so long as they do not infringe on the rights of others. In Israel’s case, this means preserving the Jewish character of the state.

The argument I will present here is framed mainly within the discourse of human rights, including the right of peoples, under certain conditions, to self-determination. Such an argument begins by recognizing the uniqueness of peoples and by acknowledging as a universal principle their right to preserve and develop that uniqueness. This starting point may seem shallow or even offensive to some Jews, particularly those for whom the Jewish right to a state and to the Land of Israel is axiomatic, flowing inexorably from Jewish faith or history. According to this view, neither the long exile of the Jews nor the fact of Arab settlement in the areas where the ancient Jewish kingdom lay undermines the Jewish claim, which is absolute and unquestionable, an elemental point of religious belief.

In my view, it is crucial to base the justification of a Jewish state on arguments that appeal to people who do not share such beliefs. We must look instead for a justification on universal moral grounds. This is the only sort of argument which will make sense to the majority of Israelis, who prefer not to base their Zionism on religious belief, or to those non-Jews who are committed to human rights but not to the Jews’ biblically based claims. Moreover, such an argument may have the added benefit of encouraging Palestinians to argue in universal terms, rather than relying on claims of historical ownership or the sanctity of Muslim lands. Locating an argument within the discourse of universal rights is, therefore, the best way to avoid a pointless clash of dogmas that leaves no room for dialogue or compromise.

Justifying the principle of a Jewish nation state, however, is only part of protecting the future of Israel. No less important is demonstrating that the state in fact can uphold, and does uphold, the principles considered essential to any civilized government, including the maintenance of a democratic regime and the protection of human rights. Accordingly, after presenting the arguments that support the existence of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel in principle, I will go on to discuss how such a state ought to be fashioned—that is, how its policies and institutions should be crafted so as to help preserve the country’s Jewish character without violating its basic obligations to both Jews and non-Jews, in Israel and abroad.

One commonly held view of liberal democracy asserts that the state must be absolutely neutral with regard to the cultural, ethnic, and religious identity of its population and of its public sphere. I do not share this view. I believe such total neutrality is impossible, and that in the context of the region it is not desired by any group. The character of Israel as a Jewish nation state does generate some tension with the democratic principle of civic equality. Nonetheless, this tension does not prevent Israel from being a democracy. There is no inherent disagreement between the Jewish identity of the state and its liberal-democratic nature. The state I will describe would have a stable and large Jewish majority. It would respect the rights of all its citizens, irrespective of nationality and religion, and would recognize the distinct interests and cultures of its various communities. It would not, however, abandon its preference for the interests of a particular national community, nor would it need to.

The Jewish state whose existence I will justify is not, therefore, a neutral “state of all its citizens.” Israel has basic obligations to democracy and human rights, but its language is Hebrew, its weekly day of rest is Saturday, and it marks Jewish religious festivals as public holidays. The public culture of this state is Jewish, although it is not a theocracy, nor does it impose a specific religious concept of Jewish identity on its citizens. No doubt this kind of state should encourage public dialogue about the relationship between its liberal-democratic nature and its commitment to the preservation of Jewish culture. In what follows, I will offer an argument for the justification of an Israel that is both proudly Jewish and strongly democratic—and that has the right, therefore, to take action to preserve both basic elements of its identity.4

II.

I begin with the premise that peoples have a right to self-determination in their own land. Exercising this right, however, does not necessarily depend on establishing a sovereign state. Self-determination can be achieved, for example, by securing cultural autonomy within a multi-national political framework.5 Yet a nation state—a state whose institutions and official public culture are linked to a particular national group—offers special benefits to the people with whom the state is identified. At the same time, it puts those citizens who are not members of the preferred national community at a disadvantage. Whether it is just to give the advantage to one people at the expense of another is a question that cannot be answered a priori. Rather, we must take into account the competing interests of the different parties, as well as their relative size and the political alternatives available to each of them. The starting point for our justification of the Jewish state, then, is an examination of the advantages of such a state for the Jewish people—in Israel and elsewhere—as compared to the disadvantages it poses for other national groups within its borders.

While a vibrant Jewish state plays a variety of roles in the lives of Jews, we must not forget the circumstances that gave rise to the Zionist dream. It is well known that Zionism emerged as a response to two interrelated problems: the persecution of the Jews on the one hand, and their widespread assimilation on the other. Of the two, the concern for the security of the Jewish people predominated: for years, the Zionist movement claimed that only a Jewish state could ensure the safety of Jews around the world. Today, however, it is fair to ask whether this claim has really stood the test of time. After all, the Jewish people survived for two millennia without a state, often in the most difficult of conditions. In recent generations, particularly in Western countries, Jews have enjoyed an unprecedented level of security and freedom of cultural expression. Perhaps this recent success stems in part from the sense of belonging Jews feel toward Israel, and the knowledge that there exists in the world a country committed to their safety. It may also be a result of lessons the world learned from the destruction of European Jewry. But these alone do not seem to justify the claim that a Jewish state is somehow essential for Jewish survival. Even the clear rise in anti-Semitism throughout the diaspora over the last few years does not decide the issue. While some argue that this new trend is merely the emergence of previously suppressed anti-Semitic sentiments, we should not dismiss out of hand the claim that this renewed anti-Semitism is, at least in part, a response to Israel’s behavior in its ongoing conflict with the Palestinians. Moreover, Israel’s ability to protect its own Jewish citizens appears tragically limited—a fact made brutally clear by the murder of hundreds of Jewish civilians by Palestinian terrorists since September 2000. Nevertheless, there is one form of anti-Semitism that is inconceivable in a Jewish state: the state-sponsored, or state-endured, persecution of Jews. The trauma of systematic oppression that was the lot of every previous generation of Jews stops at the borders of the Jewish state.6

The problem of assimilation presents Israel with a different challenge. Israel offers the possibility of a richer Jewish life than could ever be found in the diaspora, and not merely because Israel is the only country with a Jewish majority. The public culture of the state is Jewish, the language of the country is Hebrew, national holidays commemorate Jewish religious festivals and historical events, and the national discourse is permeated with concern for the fate of the Jews. In addition, state lands, immigration, and the defense of the civilian population are all in the hands of a Jewish government. In just half a century, Israel has become home to the strongest Jewish community in the world—a role that is likely to become even more pronounced in the years ahead, as assimilation and emigration gradually reduce the power and influence of Jewish communities in the diaspora.7

For observant Jews—even those who are opposed to Zionism—the advantages of a Jewish state are obvious. Certainly anyone who has practiced an observant lifestyle in both Israel and the diaspora knows how much easier it is in the Jewish state. In addition, Orthodox Jews in Israel fulfill the commandment of yishuv ha’arets, of living in the Land of Israel. While a Jewish state may not be absolutely necessary to fulfill this commandment, its absence might make it very difficult for Jews to remain here.8

A less obvious yet arguably greater advantage of a Jewish state is the cultural reinforcement it offers to secular Jews, whose Jewish identities are more fluid and generally lack the internal safeguards possessed by their Orthodox counterparts. For only in Israel, with its Jewish public culture, can Jewish identity be taken for granted as the default option, and the cultivation of any other identity require a special effort–the kind of effort all too familiar to diaspora Jews, who must struggle daily to maintain their links to Judaism.

In addition to offering Jews a safe haven from the forces of assimilation, a Jewish state offers the possibility of an exceptionally vibrant secular Jewish life. Since the rise of the Zionist movement, the Jewish people has witnessed the creation, in Hebrew, of countless new works of literature, poetry, and philosophy, whose wellsprings of inspiration are Jewish beliefs, customs, and history. This immense creative activity benefits Jews everywhere, for it offers wide new possibilities for a Jewish identity that is not dependent on halakhaa, or Jewish law.

For Jews in both Israel and the diaspora, then, the loss of the Jewish state would mean the loss of all these advantages. Without a Jewish state, the Jews would revert to the status of a cultural minority everywhere. And as we know from history, the return of the Jews to minority status would likely mean the constant fear of a resurgence of anti-Semitism, persecution, and even genocide—as well as the need to dedicate ever more resources to staving off assimilation. I do not feel that I am being overly dramatic, then, if I say that forgoing a state is, for the Jewish people, akin to national suicide.

The benefits of Israel for Jews are mirrored, at least in some respects, by the price it exacts from its Arab citizens. For in a Jewish state, Arab citizens lack the ability to control their own public domain. The national language and culture are not their own, and without control over immigration, their ability to increase their proportion in the overall population is limited. Furthermore, their personal and cultural security are dependent on the goodwill and competence of a regime they perceive as alien. All these are harder for Arabs to accept since they used to be a majority in the land, and have become a minority despite the fact that they remained on their land. The Jewish state is thus an enterprise in which the Arabs are not equal partners, in which their interests are placed below those of a different national group—most of whose members are newcomers to the land, and many of whom are not even living in the country. In addition, as we shall see, the establishment of Israel has had a major impact on the lot of Palestinians who are not its citizens. It follows, then, that the case for a Jewish state must weigh the advantages it brings to Jews against the burdens it imposes on its Arab citizens.

III.

Balancing Jewish and Arab claims to self-determination in the Land of Israel (or Palestine) is not a matter of abstract rights-talk. Rather, such claims must be addressed according to the demographic, societal, and political realities that prevail both in the Middle East and in other parts of the world. It thus follows that the degree to which a Jewish state in the Land of Israel is justified does not remain constant, but instead varies over time and according to changing circumstances. Indeed, it is my contention that at the beginning of the 20th century, when the Zionist movement was in its formative stages, the Jewish people did not have the right to establish a state in any part of Palestine. By the time statehood was declared in 1948, however, the existence of a thriving Jewish community with a political infrastructure justified the creation of a Jewish state. Today, Israel has not only the right to exist but also the right to promote and strengthen its Jewish character. Indeed, this dramatic shift in the validity of the Jewish claim to statehood is one of Zionism’s major achievements.

This approach necessarily distinguishes between claims regarding the legitimacy of Israel’s creation and claims regarding the right of Israel, once established, to maintain itself as a Jewish state. Such a dichotomy contrasts sharply with the view of most Arab leaders and intellectuals, who insist that Israel was wrongfully established and that its continued existence today is ipso facto unjustified. It is important to see that the two are not necessarily connected. For even if there was no justification for the creation of a Jewish state in 1948—a claim which I do not accept—it does not follow that the preservation of Israel as a Jewish state is unjustified today. Similarly, even if we accept the establishment of Israel in 1948 as justified, one would still have to show why the preservation of Israel’s Jewish character is legitimate today. The point here is that changing conditions affect the balance of legitimacy, and therefore no claim to self-determination can be absolute. This approach, which may appear at first glance to weaken the case for the Jewish state by making it contingent, to my mind provides one of the strongest universal arguments in its favor.

To see why this is so, it is instructive to divide the history of modern Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel into five distinct periods, and to consider the degree to which a Jewish state was justified in each of them. Relevant factors include the size of the Jewish and Arab populations in the Land of Israel or in parts of it; the alternatives available to the two communities; the situation of Jewish communities in the diaspora; the relationship of the Jewish people to the land; Jewish-Arab relations; the decisions made by those in charge of the territory prior to statehood; and the status of Arab citizens under Israeli rule.

The first period covers the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, when the Zionist idea was first translated into concerted action. There is no disputing the fact that, at the time, the Arab population in Palestine was far greater than that of the Jews, despite the steady stream of Jewish immigration throughout the preceding generations.9 This disparity reflected the centuries-long absence of a Jewish majority in the Land of Israel, initially the result of expulsions and persecutions and later of free choice. In this period, the Jewish people did not have the right to establish a state in any part of the Land of Israel, for the right of a people to establish a state in a given territory requires that it constitute a clear majority in all or part of it. The Jewish people may have longed for and prayed toward their land, but very few chose to make it their home.10

The important question concerning this period, however, is not the right of the Jews to sovereignty in Palestine, but rather their liberty to create a settlement infrastructure that would enable them to establish a Jewish state at a later date. From the Arab perspective, such settlement was illegitimate at its core, since it was harmful to Arab interests and limited their control over the public domain. The claim that Jewish settlement harmed Arab interests is certainly understandable, and the fears that lay at its core were no doubt warranted. But did these fears place a moral obligation on the Jewish people to refrain from returning to their homeland?

I do not believe so. To understand why this is the case, it is useful to employ the distinction between “rights” and “liberties” first introduced by the American jurist Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld. According to Hohfeld, we may speak of a liberty when there is no obligation to act or refrain from acting in a certain manner. A right, on the other hand, means that others have an obligation not to interfere with, or to grant the possibility of, my acting in a certain manner. Using this model, we may say that as long as their actions were legal and non-violent, the Jewish settlers were at liberty to enlarge their numbers among the local population, even with the declared and specific intent of establishing the infrastructure for a future Jewish state.11 Their liberty to create such an infrastructure was certainly greater, for example, than that of England and Spain to settle the Americas, and Palestine was certainly a more legitimate destination than Uganda or Argentina. The immigration of Jews to Palestine was vastly different from colonialism, both with respect to their situation in their countries of origin and with respect to their relationship with the land itself. Unlike colonial powers, the Jews were a people in exile, foreigners wherever they went; they were everywhere a minority, and in some places persecuted relentlessly; and they had never possessed national sovereignty over any land but the Land of Israel. Add to this their profound cultural and religious bond to the land, and you have a solid basis for a unique connection between the Jews and the Land of Israel–one far more compelling than the claims of a typical group of European settlers.

It was in fact precisely the power of this connection that made the local Arabs see Jewish immigration as far more threatening than any influx of English or French colonists. In light of the Jews’ historical connection to the Land of Israel, the Arabs correctly understood the waves of Zionist immigration as something new, unlike the conquest of the Crusaders during medieval times or the settlement of the British under the Mandate.12 Considering the threat that Jewish settlement posed to the continued existence of a Muslim public culture in Palestine, the Arab population certainly had full liberty to take steps to resist this settlement, so long as they did not infringe on any basic human rights or violate the laws of the land. Thus, while the Arabs’ success in persuading the authorities to limit immigration and land purchases was a setback to Zionism, it was in no way a violation of the Jews’ rights.

When the Arabs realized that diplomatic measures alone could not prevent the creation of the infrastructure for Jewish settlement, however, they turned to violence as a means of resistance. This clearly was a violation of the rights of the Jews, and it was here that the great tragedy of Jewish-Arab relations began. The violent resistance of the Arabs ultimately lent significant weight to the Jewish claim to a sovereign state, and not merely to self-determination within a non-state framework. From the 1920s until today, one of the strongest arguments for Jewish statehood has been the fact that the security of Jews as individuals and as a collective cannot be secured without it.

Both Jews and Arabs attach great importance to this early period, and both sides continue to ignore certain facts about it. The great majority of Arabs believe that Jewish settlement was both illegal and immoral; even those willing to accept the current regime still refuse to recognize the legitimacy of the Jewish national movement. As a result, we hear the constant repetition of the claim that Zionism is, by its very nature, a form of both colonialism and racism.13 On the other hand, many Jews refuse to accept that Arab objections to Zionist settlement are not only legitimate, but almost inevitable. Now as then, Arab violence turns Jewish attention to the need for self-defense, and few are willing to admit that the original Zionist settlers did not come to an uninhabited land, or that they posed a real threat to local Arab interests.14 As long as each side continues to deny the other’s narratives, hopes, and needs, reconciliation and compromise over the long term are unlikely.

In the second period of the conflict, from the Arab Revolt that began in 1936 to the United Nations partition decision of November 1947, a number of attempts were made to find a solution acceptable to the international community and reflective of the reality in the Mandate territory. While the details differed, each plan suggested division of the territory into Jewish and Arab states in accordance with demographic concentrations, providing for the rights of those who remained outside their own nation state. This approach derived from the recognition of two basic facts: that a critical mass of Jews had formed in Palestine, in certain areas constituting a clear majority; and that the only hope for the region lay in a two-state solution. From the perspective of both sides to the conflict, this approach signaled both a major achievement and a serious setback. The Jews had succeeded in winning international recognition for their right to a sovereign state. The Arabs had succeeded in preventing that state from encompassing all of the territory west of the Jordan River, as was implied in the Balfour Declaration. The ultimate expression of this new approach was the partition plan ratified by the UN General Assembly on November 29, 1947. The Jewish and Arab responses could not have been more different: the Jews accepted partition and declared independence; the Arabs categorically rejected the UN plan and went to war.

The third period, which includes Israel’s War of Independence and its immediate aftermath, was one of decisive victory for one side and crushing defeat for the other. When the smoke of battle had cleared in early 1949, the new State of Israel controlled a much larger area than had originally been allocated to it by the UN plan, and the remaining territories were seized by Jordan and Egypt. Hundreds of thousands of Arabs left the Jewish territory either voluntarily or under duress. Many Arab villages were ruined or abandoned.15 The Arab minority that remained in Israel was placed under military rule.

In the Palestinian narrative, this chain of events is known as al-nakba, the “Catastrophe,” the formative experience upon which the Palestinians’ dream of return and the restoration of the status quo ante is founded. The official political expressions of this ambition have changed over time: there are major differences between the language of the Palestinian National Covenant as approved in 1968, the PLO’s declaration of 1988 accepting the UN partition plan (albeit with reservations), and the 1993 Oslo Accords, which recognized Israel’s existence and agreed to peaceful relations. Despite the progress implicit in each of these declarations, however, nowhere has the Palestinian movement given up on its dream of return. The centrality of this issue is impossible to understand without a closer look at the events of 1947 through 1949.

There is no doubt that the consequences of this period were tragic for the local Arab population. This is not to say, however, that the exclusive or even prime responsibility for this tragedy rests on Israel’s shoulders. Indeed, it is encouraging that a tendency has developed in recent years, both in the academy and in the Israeli public, to examine more critically the events that occurred both during and after the War of Independence. There is, it seems, a growing awareness that no good can come of bad history. Fortunately, while these examinations may shatter the myth of moral purity that Jews have ascribed to their side in the war, they may also reinforce the more substantive Jewish claims. The Arabs themselves bear a great deal of responsibility for the region’s miseries during this period, which were brought on by a war which they themselves declared. After all, the purpose of the war was to prevent the establishment of the Jewish state. If the Arabs had won, they would not have allowed such a state to come into being. The Jews, therefore, had no alternative but to fight to defend their state.16

After the war, Israel signed cease-fire agreements with Jordan and Egypt that did not reflect the UN partition map. Nor could they have: the Palestinians lacked any official representation with which to reach a postwar settlement. More importantly, the war had rendered irrelevant the vision of two democratic nation states, living side by side under joint economic administration. In light of the Arab states’ refusal to recognize Israel, no settlement on the issues of Palestinian statehood and refugee absorption could possibly have been reached.

In the fourth period, between 1949 and 1967, Israel had full jurisdiction over its new borders. Immigration, largely from Europe and from Arab countries, dramatically altered the country’s demographic balance: whereas the pre-1947 Jewish majority was a bare 60 percent in its territory, the state of Israel soon boasted a Jewish population nearing 80 percent.17 During these years, the state consolidated control over its territory through widespread nationalization of land, including “public” lands that had been used by Palestinians, as well as abandoned areas. The enraged Palestinian community, now under military rule, was unable to mount an effective protest.18

The results of the war brought an end to the symmetry between Arabs and Jews. Palestinian Arabs did not achieve statehood, and their communities suffered a major setback, while Zionism made a critical transition from having the moral liberty to establish a Jewish state to having a moral right to maintain it and to preserve its Jewish character.

The regional war that broke out in 1967 marks the beginning of the fifth period, a period that has continued, in one form or another, until today. The Six-Day War was another attempt by the Arab states to transform the political reality in the region through the destruction of the Jewish state. Once again their efforts failed, and Israel’s overwhelming victory included the seizure of the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the West Bank and eastern Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

One important consequence of the Six-Day War was the revival among Jews of a controversy that appeared to have been settled with the partition plan and the establishment of the state of Israel: the controversy regarding those territories that had once been part of the historic Land of Israel but did not fall within Israel’s pre-1967 borders. In the face of the Arab refusal to negotiate with Israel after the Six-Day War, intensive Jewish settlement began in some of these territories. In the years that followed, important political developments continued to affect the territories’ status: Israel imposed its civilian law on the whole of Jerusalem (immediately after the war) and on the Golan Heights (in 1981), yet refrained from doing so in the other areas it had seized. The Sinai Peninsula in its entirety was returned to Egypt as part of the Camp David peace accords of 1978, and Jordan waived its claims to the West Bank in 1988 and signed a peace agreement with Israel in 1994. The peace agreements with Egypt and Jordan only exacerbated the conflict between Jews and Palestinians over the fate of the strip of land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River—what Jews call the “Land of Israel” and Palestinians call “historic Palestine.” On both sides there are advocates of a unified sovereignty over the entire area, with each side claiming the right to total control. Others call for division of the land into “two states for two peoples,” and still others seek the creation of a single binational, democratic state for the entire area.19 None of this, however, undermines the basic justification for having a Jewish state in that part of the land in which the Jews constitute a large and stable majority.

In the final analysis, it is impossible to ignore the profound changes that have occurred in the last hundred years with respect to the balance of Jewish and Arab interests in the Land of Israel. True, both moral and practical considerations suggest that Israel should give up on maximalist claims to sovereignty over the entire area west of the Jordan River. A situation in which both Jews and Palestinians can enjoy national self-determination in part of their historic homeland is better than the present asymmetry between them.20 At the same time, however, justification for the existence of a Jewish state in part of that land is stronger now than it was in 1947. This is not because of Jewish suffering during the Holocaust or the guilt of the nations of the world, but rather because Israel today hosts a large and diverse Jewish community with the right to national self-determination and the benefits that it can bring. The need to recognize the trauma of Palestinian refugees does not justify a massive uprooting of these Jews, nor does it justify the restoration of the demographic status quo ante between Jews and Arabs, or otherwise restoring the state of vulnerability which both communities endured.

While we cannot ignore the history of the conflict, neither can we ignore the reality that has taken hold in the intervening years. Nowhere is this more important than in considering one of the basic Palestinian claims, according to which hundreds of thousands of Palestinians should be allowed to relocate to Israel through recognition of what is known as the Palestinian “right of return.” In evaluating this claim, one must first recall that a necessary condition for the existence of a Jewish state is the maintenance of a Jewish majority within its borders. It follows that Israel must not extend its sovereignty over a sizable Palestinian population, and that it must continue to maintain control over immigration into it. This control, and the Jewish majority in Israel, will both be undermined by recognition of a “right of return.” It is therefore crucial to see that behind all the talk about rights and justice, the “right of return” necessarily means undoing the developments in the region since 1947, and undermining the existence of a Jewish state.21

A Palestinian state alongside Israel, however, would help address the claims of Arab Israelis to the effect that Israel must give up its national identity because only then would Arab citizens enjoy full equality within it. It is true that Arabs cannot enjoy a sense of full membership in a state whose public culture is Jewish. This is especially the case so long as there is a violent, unresolved conflict between their people and their state. At the same time, however, the sense of not being full partners in the national enterprise is the lot of national minorities in all nation states. This complaint should be distinguished from demands for civic and political non-discrimination for Arabs as individuals, and recognition of their collective cultural, religious, and national interests, which Israel should provide.

It is undoubtedly true that in Israel a significant gap exists between the welfare and political participation of Jews on the one hand and Arabs on the other. This is, in part at least, the result of various forms of discrimination. But does this fact undermine the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish state? Again, differences between Jews and Arabs in Israel are no greater than between majority and minority nationalities in other countries.22 And while it is true that any comparison of the status of Israeli Arabs will principally be with that of Israeli Jews, it is worth bearing in mind that their situation is in many respects far better than it would be in an Arab state. This is most evident in the areas of education, health, and political freedom. Even their level of personal security is relatively high: cases of physical abuse by the state authorities are quite rare.23 It is therefore not surprising that despite the real difficulties of life in Israel, the majority of Israeli Arabs do not want their homes to become a part of an eventual Palestinian state.

The life offered Israeli Arabs by the Jewish state does indeed limit their ability to develop their culture and exercise their right to self-determination, but this is far from being sufficient grounds for abolishing the Jewish state. As we have seen, the Jewish state fulfills an important set of aims for Jews and for the Jewish people–aims that the Jews have a right to pursue, and which could not be realized without a state. It is possible, then, to justify the limited harm done to the individual and communal interests of Arabs in light of the mortal blow Israel’s absence would be to the Jewish people’s rights. The reasoning for this is straightforward: there is a great difference between preferring the interests of one group over those of another and the denial of rights: as human beings, we all have a right to life, security, and dignity, as well as to national self-determination. We cannot, however, demand that the government protect all our interests and preferences at all times. The state is justified in weighing the interests and preferences of different parties, and the resulting arrangements, although always to the detriment of one group or another, do not in themselves constitute a violation of rights. In a democracy, these arrangements are made primarily by elected representatives, and as a result they usually reflect the interests and preferences of the majority. It is therefore a fundamental principle of democracy that no minority has the right to prevent the majority from advancing its interests, so long as the minority’s basic rights are respected.24

In other words, so long as the Jewish character of the state does not infringe on the basic human rights of those Arabs living within Israel, and the state is the only guarantee of certain Jewish rights—both individual and communal—then the continued existence of a Jewish state is justified. Palestinian self-determination, therefore, should be recognized if it concedes the right ofJews to self-determination. At the same time, a Palestinian nation state living in peace alongside Israel is preferable to the present situation, for this would mean that the rights of both Jews and Arabs to self-determination are honored.

In the abstract, a binational state between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River might be easier for many people to justify than a two-state solution. However, the logic of partition seems only to have strengthened since 1947. Those who advocate the creation of a Palestinian nation state alongside Israel cannot in good faith argue that Israel should give up its Jewish identity.

IV.

Can the Jewish state be a nation state for Jews without violating the rights of others? And if it can, have the rights of non-Jews in Israel in fact been protected? If the answers to these two questions are in the negative, we need to look again at the case for the Jewish state. In looking at both the underlying theory and the history of the Jewish state, however, we find that Israel has strived to meet these demands, and with no small measure of success. True, Israel’s record on democracy and human rights is not perfect. But neither is that of any other democratic state, and Israel has been better in this regard than many others. Indeed, when compared to the available alternatives, the Jewish state seems to be the best way to protect the rights, interests, and welfare of all groups within it.

It goes without saying that Israel’s status as a Jewish nation state does not exempt it from upholding the standards to which all states must be held. Like any civilized country, the Jewish state must provide for the security and welfare of all its citizens, and for the protection of their freedom and dignity. It must therefore be a democracy, for only democracy gives citizens the power to take an active role in decisions that affect their fate and ensures that the government will act in the people’s interests. Contrary to what is popularly believed, however, the principles of democracy, individual rights, and equality before the law do not necessitate a rejection of the Jewish character of the state. On the contrary: the fact of Israel’s democratic nature means that it must also be Jewish in character, since a stable and sizable majority of its citizens wants the state to be a Jewish one.

In addition, Israel should also be a liberal state, allowing individuals and groups to pursue theirown vision of the “good life.” This combination of democracy and liberalism is necessary not only because each is a good in its own right, but also because of the makeup and history of Israeli society. Because the country is deeply divided among people holding competing visions of the good life, the state must show the greatest possible degree of sensitivity to the rights, needs, and interests of all its constituent groups, Jews and non-Jews alike. Such sensitivity will go a long way toward engendering a sense of partnership and commitment to the national enterprise, even among those who are culturally or ethnically in the minority.

For these same reasons, democracy in Israel must be based on the sharing of power rather than simple majoritarianism; it should therefore rely on consensus-building and negotiation rather than rule through dictates of the majority. It must on the one hand accord a significant degree of autonomy (and communal self-determination) to its diverse populations, and on the other hand work to strengthen the common civic framework. Only in such a framework would a substantive public debate over the nature of the state be possible.

Probably the thorniest issue to arise in this context is the status of Israel’s Arab citizens.25 Jews in Israel tend to downplay the price Arabs pay for the state’s Jewish character. Many are hostile to Arab demands for equality, seeing in them a veiled existential threat. There is a reluctance to grant the Arabs a distinct collective status, coupled with a reluctance of the Jewish community to encourage the assimilation of non-Jews into Israeli society—a reluctance which finds its parallel in the Arab community, as well. These sentiments are in part responsible for the very limited integration of Jews and Arabs in Israel. At the same time, some Jews are moved by a sense of guilt over wrongs committed by the state against its Arab population, and have chosen to join with the country’s Arab citizens in advocating the abandonment of the idea of Israel as the nation state of the Jews. According to this view, true equality can be achieved only through the privatization of all particularistic affiliations. For their part, Israeli Arabs do demand full civic equality, but in addition they demand official recognition of their status as a national, cultural minority—a demand that is not consistent with their demand to “privatize” the national and cultural sentiments of the Jewish majority. A similar inconsistency obtains with respect to their attitude towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They claim the right to identify politically and publicly with the national aspirations of the Palestinian people. At the same time, they claim that this open identification should have no bearing on their treatment by the state and its Jewish citizens, despite the fact that Israelis and Palestinians are locked in a violent conflict. All of these positions reflect a tendency on both sides to ignore the real conflicts of interest between the groups, which cannot be fully masked by a shared citizenship. These problems must be handled with the utmost candor, sensitivity, and creativity if they are ever to be resolved.

One should not underestimate the complexity of the problem. Many Israeli Arabs are willing, for practical purposes, to abide by the laws of the country they live in, but are not willing, under the present circumstances, to grant legitimacy to the Jewish state. They insist on justifying the Arab struggle against that state, and emphasize the price they pay for living in it. They find it difficult to pledge their civic allegiance to a state that, in their view, systematically acts against their interests and those of their people. Since Israeli citizenship was imposed upon them, they claim, they are under no obligation to uphold the duties it imposes on them.

This attitude reflects a growing, systemic alienation of Israeli Arabs from the Jewish state, and one that only perpetuates the current state of mutual distrust. Indeed, the Arabs’ refusal to accept the fact of Jewish sovereignty makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to create a civic partnership of any kind. While it is true that the main burden of taking practical measures and allocating resources falls on the state, Israeli Arabs must play a part as well, at the least by trying to offer some account of what obligations do accompany their citizenship. For example, it is clear that virtually no one expects Arab Israelis to be conscripted into the military under the present circumstances. Yet the Arabs’ categorical rejection of mandatory non-military service is difficult to justify—as is the position held by most Arab leaders that Israeli Arabs who volunteer for the IDF should be condemned or even cut off from their communities.

For their part, the Jewish majority must recognize the state’s basic responsibilities toward Israeli Arabs. This responsibility is threefold. First, Jews must recognize that the Jewish state has been and continues to be a burden for many Israeli Arabs. Again, this need not mean giving up the idea of a Jewish state, but it does require acknowledgment of the price the Arabs have paid, and will continue to pay, for its existence. This price may be justified when seen against the need of Jews for a Jewish state. But even if this need is sufficient grounds for causing Arabs to live as a minority in their land, it does not justify acting as though there were no price being paid. Second, the government should move immediately to address the most pressing needs of the Arab community, and to promote the civic equality promised in Israel’s Declaration of Independence; bureaucratic foot-dragging only undercuts the affections that Arab citizens may have for the country. Third, the conflict between the aspirations of Jewish nationalism and the status of Arabs in the Jewish state must be admitted and addressed honestly, not downplayed or dismissed. We must recognize that the needs of Jewish nationalism do, in some cases, justify certain restrictions on the Arab population in Israel, particularly in areas such as security, land distribution, population dispersal, and education. These policies must be constrained, however, by the basic rights of the Arab citizens of the state. And they should be developed through a dialogue with the Arab community, such that the policies which emerge will promote not only the state’s Jewish character, but also the welfare of Israeli Arabs.

The intensity of the conflict poses a serious challenge to Israeli democracy. We have a vicious circle here: Arab leaders express their anger and criticism of Israel in ways that strike some Jews as treasonous, and the latter respond by trying to limit the free speech of these leaders, who in turn become even more critical, depicting the state as undemocratic and censorial. What results is a no-win situation, in which there is no agreed-upon framework for legitimate discussion, further amplifying the frustration and anger of both sides. The ongoing violence has only deepened the Jewish belief that the only solution is full separation between Jews and Arabs. Naturally, many Arabs are afraid this may lead to an attempt to “transfer” them from their homes. Some of the blame, however, clearly belongs on the shoulders of those Arab leaders who deliberately fan the flames through their extreme rhetoric: while democracy cannot thrive without a robust debate on all issues of public interest, it is utterly unreasonable to expect even the most liberal of democracies to tolerate a situation in which, for example, a member of parliament openly celebrates the victory of the state’s enemy, or appears to endorse violence against its civilians as reflecting a “right to resist the occupation.” If both sides show sensitivity and restraint, we can have fruitful debate and some sense of a shared citizenship despite differences of opinion. If not, we may well lose the ability to agree on any shared framework—a potentially disastrous development.26

Beyond the question of non-Jewish citizens in Israel, the idea of a “state of the Jewish people” raises important questions surrounding the role of Jews who are not Israeli citizens—that is, the role of diaspora Jewry in shaping Israel’s character and policies. Diaspora Jews clearly have a strong interest in preserving the Jewish character of the state. This interest, however, must not be confused with the right to participate in Israel’s decision-making process. Surely someone who chooses to live in another country is obligated first to that country, and cannot insist on taking part in the decision-making of another. Moreover, the full participation of diaspora Jewry in the Israeli political process would contradict the democratic principle according to which political involvement is granted only to those who are affected directly by a government’s decisions. It should be clear, then, that neither Jews living outside of Israel nor their representatives have any political right to involvement in decisions made by Israel.

However, Israel is certainly entitled—and, I would argue, even obligated—to strengthen its ties with the diaspora. Israel has an important role to play in the lives of all Jews, not only those who live within its borders. Israel must continue to welcome Jewish youth from around the world who want to experience life in a Jewish state. Israel must offer diaspora communities both material and cultural assistance, and participate in the restoration of Jewish cultural and historical sites worldwide. There must also be an ongoing dialogue between Israel and diaspora communities concerning the nature of Jewish life in Israel, including decisions about access to Jewish holy sites or legal questions about the definition of Jewish identity. Although the final say on such matters must rest with the elected bodies of Israel, the outcome may have far-reaching implications for Jews outside Israel. Therefore, both common sense and a feeling of common destiny dictate that Israel should consult with diaspora representatives, formally and openly, when deciding on matters with consequences for the Jewish people as a whole.

V.

As we have seen, the Jewish character of the State of Israel does not, in and of itself, mean violating basic human rights of non-Jews or the democratic character of the country. Non-Jews may not enjoy a feeling of full membership in the majority culture; this, however, is not a right but an interest—again, it is something which national or ethnic minorities almost by definition do not enjoy—and its absence does not undermine the legitimacy of Israeli democracy. Israel has a multi-party political system and a robust public debate, in which the national claims of the Arabs are fully voiced. It has regular elections, in which all adult citizens, irrespective of nationality or religion, participate. Since 1977, it has experienced a number of changes in government. Its court system enjoys a high level of independence, and has made the principle of non-discrimination a central part of its jurisprudence. It has also developed a strong protection of freedom of speech, of association, and of the press. It is thus no surprise that it is counted by scholars among the stable democracies in the world.

Put another way, the idea that Israel cannot be a Jewish state without violating the tradition of democracy and human rights is based on a questionable understanding of democracy and the human-rights tradition. This tradition also includes the right of national self-determination, the fulfillment of which will always create some kind of inequality—at least with respect to the emotions that members of the majority, on the one hand, and ethnic or national minorities, on the other, feel towards their country. An honest look at the democratic tradition will reveal that the real tension is not between Israel’s “Jewish” and “democratic” aspects, but between competing ideas within democracy, which is forced to find a balance between complete civic equality and freedom for the majority to chart the country’s course. Every democratic nation state is forced to strike that balance, and it is unfair to assert that respect for civil rights and recognition of individual and collective affiliations require that Israel’s character be based solely on neutral, universal foundations.27 The state and its laws should not discriminate among its citizens on the basis of religion or nationality. But within this constraint, it can—and in some cases it must—take action to safeguard the country’s Jewish character.28

The Law of Return is a prime example. The law serves a number of crucial aims, including offering refuge for every Jew and strengthening the Jewish majority in Israel. Its most important task, however, is symbolic. After all, the right of Jews to settle in their land, and the belief that the Jewish state would offer Jews everywhere a place to call home, has always been the lifeblood of Zionism. Thus, when the Law of Return was enacted in 1950, there was a widespread sense that the right of any Jew to immigrate to Israel preceded the state itself; it was a right that the law could declare but not create. Perhaps this particular claim was a bit questionable: there is, in fact, no “natural right” of Jews to immigrate to Israel. Had a Palestinian state been established instead of a Jewish one, it is reasonable to assume that it would not have recognized the right of Jews to move there, nor is it likely that international law would have done so. But once the idea of a Jewish national home became internationally recognized and a Jewish state was established, Israel was fully justified in including the right of all Jews to immigrate there as one of the state’s core principles.

There are those who argue that the Law of Return is racist, one of the clearest proofs that Arab Israelis are the victims of state-sponsored discrimination. This claim is baseless. The law does not discriminate among citizens. It determines who may become one. The principle of repatriation in a nation state is grounded in both political morality and international law. The United Nations’ 1947 resolution approving the establishment of a Jewish state was meant to enable Jews to control immigration to their country. Similar immigration policies based on a preference for people whose nationality is that of the state have been practiced in European countries, including many of the new nation states established after the fall of the Soviet Union. The need to preserve a national majority, especially in cases where the minority belongs to a nation that has its own, adjacent state, is not unique to Israel.29

Another example concerns the geographical distribution of Jewish settlement within Israel. The territorial integrity of a state is a legitimate national interest. In the context of the ongoing conflict, Israel is justified in establishing Jewish towns with the express purpose of preventing the contiguity of Arab settlement both within Israel and with the Arab states across the border: such contiguous settlement invites irredentism and secessionist claims, and neutralizing the threat of secession is a legitimate goal. By contrast, the blatant discrimination against Arabs in the quality of housing and infrastructure cannot be justified.30 The Israeli Supreme Court’s declaration in Kedan v. Israel Lands Administration (2000), according to which the state must not discriminate against Arabs in these matters, is therefore welcomed. However, I do not accept the ruling’s further implication that there is no basis for permitting the creation of separate communities for Jews and Arabs. In a multi-cultural society such as Israel, most individuals prefer to live within their respective communities, and they should be allowed to do so, provided that this does not severely undermine the common civic identity.31

A third example concerns education policy, and in particular the question of whether Israel’s educational system should openly promote Jewish identity and the state’s Jewish character in its Jewish public schools. In recent years, this has been the subject of a lively public debate, a fact that is itself highly commendable.32 However, in the heat of the argument several important issues have frequently been overlooked. For example, while it is agreed that education for Jewish and Zionist identity should not take the form of mindless indoctrination, neither is it possible to reduce education to a dispassionate exercise in the comparative study of cultures. A proper education will give students the tools they need to examine their Jewish identity with a critical eye, and in some cases this education might even lead a student to disassociate himself from that identity. But even if education cannot be value-neutral—and by definition it never is—it has to be committed to both truth and a sense of perspective. Jewish education in Israel cannot ignore the history of the Israeli-Arab conflict and the disagreements about it that prevail today. Ignoring the more unpleasant parts of the historical record only weakens students’ ability to address the conflict properly, and makes it harder for them to criticize Israel’s actions while maintaining a sense of national loyalty. The richer and more complex the sense of identity, the stronger and more secure it will be.

Obviously a different approach must be taken in the Arab sector. The educational system for Israeli Arabs should strengthen Arab cultural identity and, as a result, alleviate fears that life in a Jewish state means weakening the bonds that have traditionally connected them with the Arab people. The Israeli Arab educational system should also promote awareness of minority rights and emphasize the fact that Israel is a democracy committed to the principle of non-discrimination, even if it may fall short in practice, and that it allows a variety of legal means for defending one’s rights and dignity. Importantly, it must instill in Israeli Arabs an understanding that their Israeli citizenship is part of their identity, even if they find it wanting. This citizenship means, among other things, allegiance to the state and respect for its laws, and acknowledging the right of the majority to determine the basic character of the state.

From the argument that the ongoing presence of a Jewish state is justified, one should not draw the conclusion that Arab citizens unhappy with the state’s character should resign themselves to it. The Arabs’ political struggle to change the character of Israel is legitimate, even if I do not share their aspirations. Yet it is crucial that this struggle be conducted under two constraints: first, it should take place only within the confines of the democratic “rules of the game”; second, so long as the majority prefers to maintain Israel’s Jewish character (again, without violating the basic rights of Arab citizens), this choice is legitimate. The state is justified in acting to preserve Israel’s Jewish nature, and this fact should not be used to delegitimize the state at home or abroad. In recent years, the commitment of Arab citizens to these two conditions has been anything but clear-cut, further complicating Jewish-Arab relations in Israel.

VI.

The need for a justification for the Jewish state is not simply a matter of self-beautification, nor is it an attempt to square the circle. It is, rather, an existential need. The Jewish state will survive over time only if the majority of Jews are convinced that its existence is justified, and that it can retain its moral compass despite the difficult conditions of today’s Middle East. Unfortunately, however, many Jews prefer to ignore the question completely. As a result, our sense of justice has come to depend on our maintaining a persistent closed-mindedness. As a result many of our best people—those Jews with the greatest moral sensitivity and empathy for the suffering of others—may in the end lose their will to identify with the Jewish national enterprise and begin to view its existence as indefensible. Even worse, those of us who are morally uncomfortable with Israel’s current policies will have no real tools for determining whether these policies are in fact unjustified and should be opposed, or are indeed justified by the necessity of preserving the Jewish character of the state (so long as human rights are protected).

If we are to dispel the fog of pessimism that has recently settled over the Zionist enterprise, then, we will have to begin with a clearheaded approach. There is no point in denying that the State of Israel faces profound internal and external challenges. Israeli society is increasingly divided by economic disparity and conflicts between Jew and non-Jew, secular and religious, Left and Right. Yet the Jewish state is, in many respects, a major success, particularly when one considers the circumstances with which it must contend. In terms of democracy, Israel is far ahead of its neighbors, and far ahead of where it was in its early years. Israel’s economy and its scientific achievements place it among the world’s most developed countries. It boasts an open, self-critical society with considerable political freedom, and its rule of law and judicial independence rival those of the healthiest democracies. And these successes have come without the benefit of the rich natural resources found in other countries, including Israel’s Arab neighbors. True, Israel has not yet achieved a stable peace with many of its neighbors. We should continue to make such an agreement our goal, while remembering that its achievement does not depend on Israel alone. In the meantime, we can look back with pride and forward with hope. Israel has a great deal to offer its citizens, both Jews and Arabs.

For now, Israel is the state of the Jewish people. In the present circumstances it is justified in being so, and I hope that it will take the necessary steps to preserve this status in the future. This is no small aspiration: The history of the Land of Israel is strewn with the remains of many peoples and cultures. Israel’s Jewish majority need not apologize for seeking to retain the Jewish identity of the state, but it must recognize the rights of Palestinians living between the Mediterranean and the Jordan. This includes their right to express their own unique identity both through an independent state of their own alongside Israel, and as a minority within the Jewish state. This issue cannot be wished away; it must be addressed in a way that is both effective and moral.

The hope that the Jews of Israel will become more culturally homogeneous is also pure fantasy. Israel will never be either wholly secular or wholly religious, wholly East or wholly West. Israel will never be a Western European country, nor will it be a typical Levantine one. But the tensions that arise from these various dualities are hardly to Israel’s detriment: the strength of Israeli society is derived from the combination of its elements, and this carries an important lesson for the state’s future. Israel must struggle to protect the unique combination of cultures, traditions, and identities that make up the Jewish state. Every group should feel at home, and no one group should be capable of imposing its ways on others. If we are wise enough to uphold this principle, it will not only serve the ends of the majority, but also safeguard the uniqueness of the minorities.

“It is not for us to finish the job,” we are told by the rabbis of the Talmud.33 Our generation is not responsible for establishing a Jewish state; rather, we are responsible for preserving it for future generations, and for ensuring that it is passed on to our children as a worthy inheritance. This requires that we give them solid grounds for believing in the justice of our common enterprise—and this, in turn, means recognizing the diversity of Israel’s citizenry and the complexity of our life together. Our generation needs to channel this diversity to good ends, even when different groups disagree, or when one group’s aspirations do not line up perfectly with those of the state as a whole. The key to our success, then, will be our ability to preserve the delicate balance between what unites us and what makes us different.

If we will it, this too will be no dream.

At the time of publication, Ruth Gavison held the Haim H. Cohn Chair in Human Rights in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and was a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute. This essay is based on the Zalman C. Bernstein Memorial Lecture in Jewish Political Thought, sponsored by the Shalem Center, delivered in Jerusalem on January 25, 2001.

Notes

I would like to extend special thanks to Yoav Artzieli for his help in preparing this lecture for publication.

1. For my purposes, there is no substantial difference between the expression “Jewish state” used in this article and others employed in public debates, including “a state for the Jews” or “a state for the Jewish people,” all of which attempt to underscore the particular, unique foundation of the state of Israel. The initial appearance of the latter expression in Israeli law occurred in Clause 7a(i) of the Basic Law: The Knesset, passed in 1985, which prohibits any party that denies that Israel is “the state of the Jewish people” from standing for election. This expression was preferred over the popularly used “Jewish state,” which can be seen as having an overly religious connotation. Nonetheless, when it was pointed out that the expression “the state of the Jewish people” implies that Israel is not, in fact, a state for its non-Jewish citizens, the legislature reinserted the term “Jewish state” in the Basic Laws of 1992, wherein Israel is defined as “a Jewish, democratic state.” This was also the expression of choice in United Nations Resolution 181, of November 29, 1947, which speaks of “a Jewish state” in contrast to an Arab one, as well as in the Declaration of Independence, which called for establishing “a Jewish state in the Land of Israel.”

2. In my book Israel as a Jewish and Democratic State: Tensions and Prospects (Tel Aviv: Hakibutz Hame’uḥad, 1999) [Hebrew], I deal summarily with these preliminary challenges, and conclude that Israel as a Jewish and democratic state is both coherent and legitimate. I then concentrate on the tensions between these elements and on ways of mitigating them.

3. This misguided alliance between liberal Jews and Arab enemies of the Jewish state is strengthened by a tendency to equate the Jewish state with a Jewish theocracy. A Jewish theocracy is not legitimate, they argue, because by definition it cannot be a democracy, and because religions are not entitled to political self-determination. However, this is clearly a misreading of the term “Jewish” in a “Jewish state,” which refers not to religion but to national identity. The confusion stems from the fact that the relationship between nationality and religion in Judaism is a unique one. No other people has its own specific religion: the Arab peoples, for example, comprise Christians, Muslims, and Druze. While there was a time when the French were mostly Catholics or former Catholics, they still waged religious wars with the Huguenots, and today a large number of Frenchmen are Muslim. At the same time, no other religion has a specific nationality of its own: Christians can be French, American, Mexican, or Arab; Muslims, too, can be Arabs, Persians, or African-Americans. This distinction is not merely the result of secularization: Judaism, at least from a historical perspective, has never differentiated between the people and the religion. Nor was there any belated development that altered this unique fact: social stereotyping never allowed an individual to be a part of the Jewish people while at the same time a member of another religion; nor could one be an observant Jew without belonging to the Jewish people.

This uniqueness, however, should not cloud our thinking. The Arab challenge to the Jewish state rejects any claim to Jewish self-determination, be it based on nationality or religion. It is important that those secular Jews who insist that Jewish identity is not exhausted by religion do not allow their position in the internal Jewish debate over the Jewishness of Israel to obscure for them the legitimacy of a Jewish nation state. Likewise, the state must accept all interpretations of Judaism and Jewish identity put forth by its Jewish citizens, and provide a home for all Jews, irrespective of their attitude to the Jewish religion. In this essay, I use “Jewish” and “Jewishness” to incorporate all forms of Jewish culture and Jewish identity.

4. The Jewish character of the state is a source of tension not only between Jews and Arabs, but also among Jews. Some of the more extreme Orthodox leaders, who advocate a kind of Jewish theocracy, insist that a democratic Israel is, by definition, not Jewish. This conception of the Jewishness of Israel has been rejected by all mainstream Israeli political leaders, including Orthodox ones, and rightly so. At the other extreme, however, there are many Jews who insist that liberal democracy demands perfect neutrality with regard to religious identity, and therefore the absolute separation of religion and state. This view is misguided. A liberal political stance does not automatically mean rejecting the establishment of religion any more than it means abandoning the state’s Jewish national character in favor of a universal one. Liberal democracy does insist on freedom of religion and from religion, as is recognized in international law, but this is not the same as disestablishment: while those who call for absolute separation generally refer to the American model, there are many European democracies that ensure religious freedom while granting official status to one church or another.

These two kinds of tension surrounding Israel’s Jewish character—arising from the Jewish-Arab and religious-secular rifts—are both addressed in my book, note 2 above. In the present essay I concentrate on the Arab challenge to Jewish self-determination. For my views on some of the issues in the internal Jewish debate, see also Ruth Gavison and Yaakov Medan, A Basis for a New Social Contract Between Religion and State in Israel (Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute and Avi Chai, 2003). [Hebrew]

5. For a detailed and well-reasoned argument on the advantages of national self-determination at the sub-state level, see the writings of Haim Gans, and especially The Limits of Nationalism (Cambridge: Cambridge, 2003). Self-determination of different national groups in the framework of one state can be found, for example, in Belgium, Canada, and Switzerland.

6. There are some Jews who claim that the hatred of some in the secular Left toward the haredim is in fact a unique manifestation of anti-Semitism in Israel. This is an intriguing claim, but we should note that critical sentiments against the haredim almost never involve violence against them, or an attempt to limit their freedom to conduct their religious life.

7. There is a dispute regarding the size of various diaspora Jewish communities as a result of methodological difficulties in collecting data. According to the World Jewish Congress, the number of Jews in the United States is estimated at between 5 and 6 million; in Israel, there are 5 million. The third-largest Jewish community is in France, home to approximately 600,000 Jews.

8. There are many religious Jews who oppose the existence of a Jewish state that is not a Jewish theocracy. From this perspective, the present state of Israel may be worse than having a non-Jewish state. Yet in a non-Jewish state, the Jewish population, including the observant and ḥaredi sectors, would undoubtedly not enjoy the current level of freedom to preserve and develop their way of life. Furthermore, it is a fact that Torah learning among the Jewish people has never been as widespread as it is in Israel today.

9. According to a census taken in 1922, there were 83,794 Jews in the Mandate territory out of a total population of 757,182 (approximately 11 percent). See Dan Horowitz and Moshe Lissak, The Origins of the Israeli Polity: The Political System of the Jewish Community in Palestine Under the Mandate (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 1977), pp. 21-22. [Hebrew]

10. Why the Jews did not return to the Land of Israel in greater numbers is a vexing and complex question. For our purposes, however, the numbers and their implications are sufficient.

11. Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning, and Other Legal Essays (New Haven: Yale, 1923). Using Hohfeld’s distinction, I would assert that the Jews had the liberty to settle in the Land of Israel at the beginning of the Zionist movement, and that the local Arabs likewise had the liberty to oppose this settlement by means of political, economic, and other non-violent measures. Jews did not have a right to settle (since the Arabs did not have a duty to allow them to do so), but Arabs did not have the right to prevent them from doing so (since Jews did not have a duty to refrain, and the Arabs did not themselves control the land or make its laws; if they had, they would have legislated controls over immigration which would have denied the liberty of Jews to come). Liberties may of course clash, since the agents, by definition, are under no obligation to refrain from acting. However, once a large Jewish community had taken root—and certainly after the establishment of the state, which housed a large Jewish concentration with no other home—this community had the right to self-determination and security. A corollary of this right is the obligation of the Arabs to refrain from violence in their attempts at resistance.

12. On the whole, Arabs make a point of denying the historical-cultural-religious relationship of the Jews to the Land of Israel. Thus, at the Camp David summit in August 2000, PA Chairman Yasser Arafat questioned the historical relationship of the Jews to the Temple Mount (despite the fact that Muslim sources—even those that claim a Muslim hegemony in the land during the time of Napoleon—admit this historical relationship). Some Arabs go even further, comparing Israel to the Crusader kingdom in the hope that, in the long run, its fate will be the same. This consistent denial makes it difficult for Palestinians to accept that there are two justifiable yet conflicting claims, and consequently to reach a historic compromise. There is also reason to fear that this denial expresses the hope that the Jews of Israel do not in fact feel closely connected to their land, and that a sufficient combination of force and rhetoric will cause them either to leave or to forgo the state’s Jewish character.

13. Regrettably, the anti-Israel majority in the United Nations General Assembly succeeded in 1975 in reaching a decision, in force for a decade and a half, according to which Zionism was considered a form of racism.

14. One thinker who understood the significance of the Arab presence in Palestine was Ahad Ha’am. See “The Truth from Palestine,” in Ahad Ha’am, The Parting of the Ways (Berlin: Judische Verlag, 1901), p. 25. [Hebrew] A Zionist thinker who stressed that the Arabs could not be expected to agree to a Jewish state in their native country was Ze’ev Jabotinsky. See Ze’ev Jabotinsky, “The Iron Wall,” Jewish Herald, November 26, 1937.

15. Despite the fierce dispute surrounding the claims of the “new historians,” the picture remains reasonably clear: more than half a million Arabs left Israel during the 1948 War of Independence and in the period immediately after, forming the basis of the refugee problem that continues to plague the region to this day. There was no systematic policy of expelling or uprooting them–in fact, in some places the Arabs were specifically asked to remain, while in others they left in response to their leaders’ calls. Many Arabs, however, indeed fled from the threat of hostilities, and in certain instances were expelled. See, for example, Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949 (Cambridge: Cambridge, 1987).

16. It should be noted that there is no corresponding soul-searching in the Arab sector. Arab analyses of the period of 1947-1949 include regrets for the consequences suffered by the Palestinians, and at times even a measure of anger against neighboring Arab countries and the local Arab leadership for their failure in preventing these consequences. Yet there is almost no recognition of the fact that it was wrong for the Arabs to reject partition.

17. Different internal growth patterns between the two peoples account for an almost constant demographic ratio, despite large waves of Jewish immigration over the last 50 years. For details, see Issam Abu Ria and Ruth Gavison, The Jewish-Arab Rift in Israel: Characteristics and Challenges (Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute, 1999), p. 16, table 1. [Hebrew]