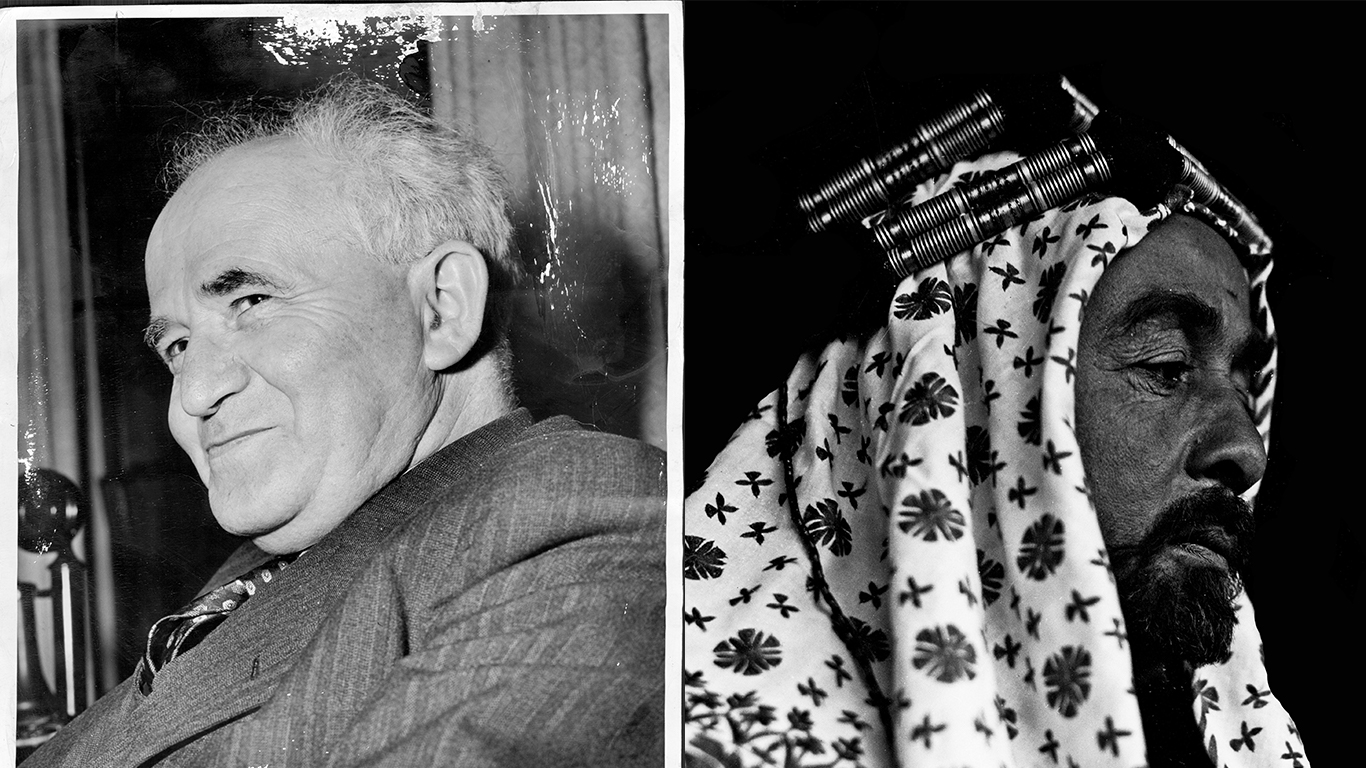

Seventy-five years ago, a world map would not have shown the names of either Israel or Jordan. Both states, the one Jewish, the other Arab, are relatively new, the products of two national movements. Although both had many founders, two men stand out as founding fathers: David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, and Abdullah bin Hussein, the first king of Jordan.

The two men, born within four years of each other in the 1880s, forged their respective states in battle and established them on firm foundations. Although one is a democracy and the other a monarchy, both emerged out of the same political womb: the British mandate for Palestine (including Transjordan), conferred by the League of Nations in 1922. In that sense, the two states were twins—far from identical twins but still inextricably tied to each other in conflict or cooperation. As for the founding fathers themselves, they never met face to face, but their personal stories are inseparable.

Those stories unfolded over four historical stages. First, as young men, both Abdullah and Ben-Gurion were drawn into the early-20th-century whirlwind of a world war, the collapsing Ottoman empire, and the stirrings in the Middle East of national revival. Next, both spent the better part of two decades, the 1920s and 1930s, building up their personal and political base in the shadow of other men. Then, in the 1940s, a second world war and a second retreating empire, in this case Great Britain, put the two men on a collision course. Finally, in 1948-49, in the aftermath of that collision, they reached an armistice and a de-facto partition of the contested land, and in so doing realized the better part of their respective dreams.

The four-part story ended in 1951 when Abdullah was cut down by an assassin; Ben-Gurion would have another decade-plus in politics. But there’s more to it than just a sequence of historical events. At a closer look, the two men’s biographies and political evolution disclose, in each stage, a remarkably striking pattern of similarity—of parallelism.

Let’s take a closer look.

The initial parallelism is that neither Abdullah nor Ben-Gurion was born within the territory of the state he would eventually found. Abdullah, the elder of the two, was born in 1882 in Mecca, then part of Ottoman Arabia—more than 900 miles from Amman, the capital of the future state of Jordan. Ben-Gurion was born in 1886 in Płońsk, a town in Poland 2,500 miles from Jerusalem, the capital of the future state of Israel. In their youth, both men were thus strangers to the geographical, social, and political landscapes of the states they would found.

In this case, the parallelism was hardly decisive. For one thing, their birthplaces were in no way comparable. Płońsk, lying about 40 miles from Warsaw, was a typical market town of Jews and Poles whose only claim to fame today is that David Ben-Gurion was born there. By contrast, Mecca, the birthplace of Abdullah bin Hussein, was and is the great holy city of Islam, made so by the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century: the place to which Muslims around the globe turn in prayer five times a day and to which millions of Muslims undertake pilgrimage every year.

For another thing, the two men’s family backgrounds were wholly disparate. Ben-Gurion’s father was a lawyer and the leader of a local branch of the early Zionist movement Ḥovevei Tsion. But the family had no link to Jewish aristocracy in the form either of a rabbinic dynasty or of one of the great Jewish houses of banking or commerce. His biographer Anita Shapira refers to his origins as “plebeian”; he himself would recall his family as belonging “to the middle or professional group, neither rich nor poor but comfortably off.” However defined, it was these Jews who flocked to the nascent Zionist movement, and Płońsk itself, in Ben-Gurion’s telling, “sent the highest proportion of Jews to the Land of Israel from any town in Poland of comparable size.” Such obscure places, fertile ground for the Zionist revolution, could carry obscure people into history.

Abdullah, for his part, not only was born in the center of Islam but possessed a pedigree stretching back in an unbroken patrilineal line to Muhammad. That is, he was a sharif, a nobleman, a 39th-generation direct descendant of the prophet through the Hashemite line. True, Mecca had never been the capital of an independent state, but Abdullah’s ancestors often governed it as vassals of the Muslim rulers of Egypt or Syria or later of the Ottoman Turks. Hence the title “emir of Mecca” held by some of his ancestors. Being born to Arabian aristocracy would be important later for Abdullah, helping him to gain British support for his family’s ambitions as well as Arab support from sources outside Arabia.

Finally, more than geographical distance—Płońsk and Mecca are 3,400 miles apart—or communal status lay between David Ben-Gurion and Abdullah bin Hussein. The greater distance was between Jew and Arab, Judaism and Islam, Europe and Asia, people and tribe, commoner and nobleman.

And yet, history would propel them along not only parallel but finally convergent tracks. One of those tracks was nationalism. Both Ben-Gurion and Abdullah started life on the edges of large empires ruled from far away. Płońsk was in so-called Congress Poland, part of the former Polish commonwealth incorporated by conquest into the Russian empire. Mecca was in the Hijaz, part of Arabia incorporated by conquest into the Ottoman empire. It was at the margins of such fraying empires that nationalist ideas took root and spread in the late 19th century as it became possible to imagine liberating oneself and one’s countrymen from the shackles of a distant imperial capital. This was the shared DNA of both Jewish and Arab nationalism in the modern era: the conviction that a people subject to rule by another people could not be free.

For Jews in the Russian empire, entailed in this conviction was the need to move elsewhere. For the Arabs of the Ottoman empire, entailed was the need to rebel. Neither option was easy. Situating themselves at the forefront of the national awakenings of their peoples, Ben-Gurion and Abdullah faced a shared problem: the particular territory on which each wished to write a new, national history was still in the grip of the Ottomans, an empire that refused to fall. Long known as the “sick man of Europe,” the Ottoman empire had been in retreat since the 17th century but still survived on the Bosphorus, its grip in Asia still unbroken.

Both men, then, first tried their hand at politics in the imperial capital of Istanbul. Abdullah boasted the longer experience. In 1893, when he was only twelve, his father, the Sharif Hussein bin Ali, was summoned to Istanbul and kept as a kind of prisoner there with his family while a rival branch of sharifs was installed by the Turks in Mecca. Over the next sixteen years, Abdullah grew up in Istanbul, added fluent Turkish to his native Arabic, and after the 1908 revolution of the Young Turks became a deputy himself in the Ottoman parliament, representing his father who by then had been restored to Mecca.

Abdullah served in the parliament for five years, learning the strengths and weaknesses of the Turks and deciphering the designs of foreign powers. He was, in short, no simple Bedouin.

Ben-Gurion arrived in Palestine only in 1906. After a stint of pioneering, he came up with the idea that he, too, would go to Istanbul, study law, and become a deputy in the Ottoman parliament. In 1911 he moved to Saloniki, now in Greece but then a major Ottoman port with a large Jewish population. His purpose: to learn Turkish. In 1912, he moved on to Istanbul to study law at the university. His friend Yitzḥak Ben-Zvi, a future president of the state of Israel, accompanied him; a famous photograph shows the two of them wearing the tarboush. Ben-Gurion stayed and studied in Istanbul until 1914; with the outbreak of World War I, the Turks expelled both him and Ben-Zvi from the empire.

To be in Istanbul in those years was to see an empire in its death throes. The Hashemites, Abdullah’s clan, had to be cautious, and so did the Zionists: no one knew for sure how the war would end. But, early on, Abdullah and Ben-Gurion placed the same bet: Britain would defeat the Turks and push them out of Arabia, Palestine, and Syria. Render service to Britain, and one would be rewarded in the aftermath.

World War I was the big break that both Zionists and Arab nationalists had hoped for. The British mobilized both parties to fight the Ottomans, who were then allied with the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. To win Zionist support, the Balfour Declaration of 1917 promised the Jews a “national home” in Palestine. To prompt an Arab revolt, the British promised Sharif Hussein and his sons an independent Arab kingdom in expansive borders.

Neither Ben-Gurion nor Abdullah was a star player in either the war-making or the diplomacy. It was Chaim Weizmann in London who secured the Balfour Declaration and represented the outward face of Zionism. Ben-Gurion, a largely unknown figure, had left Palestine after the war began and spent some time organizing in New York. Returning to Palestine late in the war, he served in the British-commanded Jewish Legion where he reached no higher a rank than corporal. The legion would be associated not with his name but with those of Joseph Trumpeldor and Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Abdullah played a much greater wartime role as the effective foreign minister and representative of the Hashemites to the British, in which capacity he conducted the negotiations to secure British support of the Arab Revolt against the Turks. He also took command of one of the armies in Arabia, a force numbering as many as 4,000 men. As T.E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”) later wrote, “the Arabs thought Abdullah a far-seeing statesman and an astute politician. . . . [R]umor made him the brain of his father and of the Arab Revolt.”

But Abdullah very quickly lost the initiative to his younger brother, Emir Faisal, whom the British regarded as the more serious and reliable of the siblings. Lawrence especially took to him. With guns and funds lavished upon him by the British, Faisal, advised by Lawrence, led the main column of the Arab Revolt toward Damascus. Meanwhile Abdullah languished in Arabia, laying siege to the well-entrenched Ottoman garrison in Medina.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence’s famous war memoir, devotes several devastating pages to Abdullah, whom the author portrays as Faisal’s opposite: indolent, ambitious, pleasure-loving. In a contemporary report, Lawrence dismissed Abdullah as “incapable as a military commander and unfit to be trusted, alone, with important commissions of an active sort.” In 1919 Abdullah lost a crucial battle to the marauding Saudis, who coveted the Hashemite domains in Arabia’s western provinces. It was a humiliation.

In brief, no one in 1919 would have imagined that either Ben-Gurion or Abdullah would become the founder of a state. That particular bet would have been placed instead on Weizmann and Faisal, who in that same year reached a tentative agreement between the Zionist and Arab movements and then presented their respective national claims at the postwar Paris peace conference. It was Weizmann who ran the Zionist organization and its diplomacy, and it was Faisal whose followers would declare him king in Damascus, the precious jewel in the Arab crown.

How, then, did Ben-Gurion and Absdullah rise to the top? It happened slowly, in parallel, over the 1920s and 30s.

For Ben-Gurion, two things came together. First, with the inauguration of the British mandate in Palestine, Zionists began to shift their emphasis from diplomacy to building up the yishuv, the Jewish settlement in the land. Diplomatic declarations were all well and good, but Jews made up less than 10 percent of the country’s population—only 60,000 persons in 1920—and most of them weren’t even Zionists. Strengthening the yishuv could be achieved only by young immigrant workers and pioneers. Ben-Gurion duly began his political career as a grassroots labor organizer. This was labor Zionism, represented by the Histadrut, the Jewish labor and trade union. His position as general secretary of the Histadrut became his steppingstone to political power as head of the Mapai workers’ party and the Jewish Agency.

Second, the mandate years marked, on the part of the British, a gradual retreat from their commitment to Zionism. One of its effects was to undermine Weizmann. By the 1930s, his authority had weakened to the point where Ben-Gurion could challenge him and, eventually, shunt him aside.

An analogous change propelled Abdullah to the top. In 1920, the French threw his brother Faisal out of Damascus in order to establish their own mandate over Syria. The emir’s British backers recycled him, making him king of Iraq: a mission impossible as the Iraqis were divided into feuding sects and had no use for an Arabian monarch imposed from the outside. Then, in 1933, the fifty-year-old Faisal died of a heart attack.

It was now the turn of Abdullah to shine. In the interim, since his arrival in Transjordan in 1921, he had made himself indispensable. At that time, there were perhaps 3,000 inhabitants in Amman, and half of them weren’t Arabs but Circassians: Muslim refugees from the Caucasus who were settled there by the Ottomans. As-Salt, the biggest city in Transjordan, boasted only 10,000 inhabitants. No one imagined this border region could or should be independent; at best it should be ruled from either Jerusalem or Damascus. Abdullah himself initially saw it as a mere waystation on the road to the latter destination.

But if his ambitions ran large, he had to start somewhere: he needed a base. He cut a deal with Winston Churchill, then secretary of the colonies, who made him “emir” of Transjordan and then, after adding that territory to the Palestine mandate, severed it from the mandate’s provisions of a “national home for the Jewish people.” This allowed Abdullah to run his dirt-poor emirate as a purely Arab buffer zone—with, of course, the aid of a British subsidy.

In this capacity, Abdullah showed himself to be both pragmatic and savvy. He would start with next to nothing, and build on it—exactly as Ben-Gurion did on the other, western side of the Jordan River.

In the 1920s and 1930s, these two men—underestimated, ambitious, and driven—laid the foundations of two states. Ben-Gurion built his mostly on the party of labor. Abdullah built his largely on the tribes of the desert. Both had the same aim: to emerge from the mandate with independence.

But the British still defined the parameters of each project, and defined them narrowly. The Jews could build a “national home” in mandate Palestine, but there was no British promise of an eventual Jewish state. Similarly, while setting aside the cross-river area of Transjordan for an Arab emirate under Abdullah, the British put a damper on his expansionist dream of a greater Arab kingdom.

In the late 1930s, the British thought to get out of Palestine by partitioning the country between Jews and Arabs and linking the Arab part to Transjordan. From this point onward, Ben-Gurion and Abdullah were fully engaged with each other. But even earlier, the Zionists not only had a line out to Abdullah but were also providing him a subsidy; nor was he shy about asking for it. In a kind of symbol of the two sides’ practical cooperation, Abdullah also benefited from the power plant built by the Jews at Naharayim on the Jordan River.

The Zionists strongly favored the 1937 plan to partition the country that had been put forward by the British Peel Commission, and they hoped to enlist Abdullah’s support as well. At first he signaled his approval, but then in 1938 he came up with his own solution. In Abdullah’s plan, all of Palestine would unite with Transjordan in something he called the “United Arab Kingdom,” with presumably himself as king. In this grand scheme, the Jews would have their own self-governing administration and Jewish immigration would be allowed on a “reasonable scale.”

If this was the sum and substance of Abdullah’s first attempt to reach his hand across the Jordan river, it could not but bring home to Ben-Gurion the essential elusiveness of his putative Arab partner.

And then came World War II. As in the earlier world war, both Ben-Gurion and Abdullah aligned with Britain. For the Zionists, supporting Britain against the Nazis was not so much a choice as a foregone conclusion—a fact of which the British were well aware and quickly took advantage. In the British “White Paper” of 1939, a gesture of appeasement toward the Arabs, Britain severely limited Jewish immigration to Palestine and ruled out the establishment of a Jewish state. Ben-Gurion, by then the acknowledged leader of the yishuv as chairman of the Jewish Agency and the Zionist Executive, responded in a famous formulation: “We will fight the war [with the British against the Axis] as if there were no White Paper, and we will fight the White Paper as if there were no war.” In practice, the Jews fought only the war.

All of this makes Abdullah’s wartime stand with Britain less remarkable than it might otherwise seem. Still, in the Arab world, his stance was anomalous. Syria to the north came under Vichy French rule; Iraq in the east fell to a pro-Axis coup; the mufti of Jerusalem went to Berlin as an honored guest of Hitler; the king of Egypt flirted with fascist Italy. For an Arab to stand squarely by Britain was thus something rare, but Abdullah did it.

In May 1943, Glubb Pasha, Abdullah’s wartime British adviser (and himself a kind of Lawrence-of-Arabia figure), wrote this:

Not only have no combatant British troops been stationed in Transjordan, but Transjordan herself has provided troops, which have assisted to garrison Syria, Iraq, and Palestine. Transjordan is the only state in the Middle East the troops of which have actually fought on the British side in the present war.

Indeed, by virtue of this anomaly, Abdullah also enjoyed a favorable reputation among many Zionists. Striking evidence is to be found in a portrait of Abdullah by the Polish-Jewish-American illustrator Arthur Szyk, who in the 1930s and 40s won fame for his devastating caricatures of Hitler, Nazis, and other fascists. Moreover, Szyk himself was a member of the Bergson Group, the activist pro-Jabotinsky circle in America that believed Transjordan should be part of the future Jewish state. Yet Szyk’s 1941 portrait of Abdullah is flattering: bedecked with medals attesting to his valor, the Arab leader appears deeply thoughtful, benevolent, noble, dignified. For what reason? Because, in 1941, he stood firmly by Britain.

And here a larger fact intrudes. By this time, both Ben-Gurion and Abdullah were preparing for the postwar future—a challenge they handled in parallel, but differently.

Given the experience of the mid-to-late 1930s, Ben-Gurion had plentiful evidence that the British were in full retreat from their earlier support of Zionism. The Jews in Palestine would have to fight for themselves, and under their own command. It was in this period that he began to forge the individual self-defense militias formed by Palestinian Jews into a national army (a process I’ve analyzed in an earlier essay for Mosaic).

Ben-Gurion also anticipated the postwar rise of the United States. Going forward, American sympathy, and American Jews, would be crucial. Although he admired the fortitude of Britain and Churchill during the years of the Blitz, whose devastations he witnessed first-hand, he also spent much of the war in New York and Washington, building up the support he would need later.

Abdullah, too, appreciated the rise of the United States. But he remained dependent on Britain, the country that had honored him with a defense treaty, had helped to finance his military operations and used his territory as a base, and had dispatched advisers and commanding officers to trained his army (the Arab Legion). Even had he wanted to, Abdullah couldn’t pivot away from the British. While he never visited Washington, after the war he was a regular in London where he met with Prime Minister Clement Attlee and Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin.

As World War II ended, it became apparent that Britain would be leaving Palestine soon. Between 1946 and 1948, the Zionists and Abdullah entered into an almost continuous dialogue. The Zionists were represented by various emissaries, all of whom reported to Ben-Gurion. The divergent interests of the two men were clear. On Britain’s departure, Ben-Gurion wanted as large a Jewish state as possible west of the Jordan. On Britain’s departure, Abdullah wanted to include part or all of that same territory in his kingdom.

Could they nevertheless, somehow, cut a deal? To his credit, Abdullah understood, unlike other Arabs, just how far the Zionists had progressed since the Balfour Declaration. Indeed, he was perhaps the only Arab truly to appreciate the new reality created by Zionism. In November 1947, after the United Nations passed its own partition plan for Palestine, he said this to a Zionist emissary:

For the past 30 years, you have grown in numbers and strength, and your achievements are many. It is impossible to ignore you and it is a duty to come to terms with you. Now I am convinced that the British are leaving, and we shall remain, you and we, face to face. Any clash between us will be harmful to both of us.

If most others, including many observers in the West, felt certain that the Arabs would crush and sweep the Zionists aside as soon as the British left, Abdullah knew otherwise. This was well attested by the British diplomat Alec Kirkbride, who spent three decades managing his government’s relations with Abdullah: “The king was the only Arab ruler who had the moral courage to voice his fears about the outcome of an appeal to arms.”

At the same time, Ben-Gurion knew that—again thanks to British help—Abdullah possessed a serious military capability. The Arab Legion under its British commanders had earned a fabled wartime reputation as the best Arab fighting force in the Middle East.

Yet in May 1948, despite this mutual respect for each other’s power, and despite the desire to avoid war, Abdullah greeted Ben-Gurion’s declaration of Israel’s independence by joining the other Arab states in invading Palestine. The war between Israel and Jordan, between Ben-Gurion and Abdullah, was a fierce one. In Jerusalem, it resulted in the evacuation of the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. In the Etzion Bloc, more than a hundred Jews perished in a battle and a massacre. In the corridor to Jerusalem, where the Arab Legion at Latrun successfully held off repeated Israeli assaults, hundreds of Israelis and Jordanians died in pitched battles.

Could it have been avoided?

If Abdullah had been willing to strike a deal with Ben-Gurion and join in a British- or UN-proposed partition of Palestine, he would have had to break with the other Arabs. In November 1947, he assured Golda Meyerson (later Meir) that he would do just that. According to the Zionist report of their conversation:

He went on to ask what our attitude would be to his attempt to seize the Arab part of the country. We replied that we would look favorably on it if it did not hinder us in the establishment of our state. . . . He answered: “I want that part for me, in order to annex it to my state.” Once in Palestine, he said, he would “guard against any clash between Jews and Arabs.”

Abdullah had also warned, in his own words, that he favored “partition, but a partition that won’t embarrass me in the Arab world.” That turned out to be a very high bar. As May 1948 approached, it became clear that Abdullah was working with the other Arab states in preparing for war. Meyerson went to see him again just a couple of days before independence. Ben-Gurion, she noted, thought nothing would be lost by trying. Disguised as an Arab woman, on roads crammed with Jordanian armor and troops, she succeeded in making her way to Abdullah and confronted him with a single blunt question: “Have you broken your promise to me?”

His answer: “When I made that promise, I thought I was in control of my own destiny and could do what I thought right, but since then I have learned otherwise. I am one of five”—a reference to the five Arab states that planned to invade. Then he returned to his proposal from 1938: don’t declare independence, wait a few years, become a part of my state, you’ll be treated well.

This was a non-starter. According to Meyerson, she told him that “If war is forced upon us, we will fight and we will win.” Abdullah replied: “Yes, I know that.” At least he had no illusions.

An interesting question here is why Abdullah and Ben-Gurion didn’t meet in person. Abdullah reportedly wanted such a meeting; Ben-Gurion reportedly didn’t. Historians wonder whether Ben-Gurion missed a chance for peace. But he was convinced that in order to make a deal, Abdullah would have had to be wrestled to the negotiating table, and in any case the deal would not hold. Only war would make him treat the Jews as his equals.

Above all, for Ben-Gurion there could be no compromising on the state. He wouldn’t delay its announcement; nor would Jewish public opinion in Palestine have tolerated a delay. Just as Abdullah dreamed of a united Arab kingdom, Ben-Gurion dreamed of an independent Jewish state. There was no reconciling those fundamentally discrepant visions.

After three rounds of fierce fighting, punctuated by two truces, both sides were badly bloodied and both Ben-Gurion and Abdullah were ready to conclude a partition agreement, now between the new state of Israel and the newly named kingdom of Jordan. They reached an armistice, drew up a map, and their commanders shook hands. Ben-Gurion received what he wanted: a Jewish state in more defensible borders than those of the 1947 UN partition plan. Abdullah received what he most wanted: an expansion of his kingdom across the Jordan River and including the Muslim holy places in Jerusalem. Almost immediately, he moved to annex both eastern Jerusalem and the West Bank of the river.

Almost immediately, too, negotiations commenced on a permanent peace, with Israeli officials crossing the Jordan for secret meetings. But those negotiations soon stalled. Abdullah wanted Israel to give up some of the territory it had won in the war, especially in areas from which Arab refugees had fled. Accused at home of having betrayed the cause of the Palestinian Arabs, he needed to gain something back: perhaps Lydda and Ramleh, perhaps parts of the Negev. Eventually the talks broke off. Jerusalem became a divided city, its two parts separated by barbed wire and sniper fire. Deadly incidents made the armistice lines dangerous.

The Zionist view of Abdullah had also changed. The change is captured in another caricature by the same Arthur Szyk, this one from 1948 and the very reverse of his 1941 portrait. A bloated Abdullah, now entitled “The Melancholic Baby” and described in the accompanying text as “a fake king of a British fake called Transjordania,” sits on a rug. He keeps a begging cup marked “British subsidies” and an open copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf inscribed “To my faithful servant Abdullah with love, Ernie Bevin.” This Abdullah is a British stooge, sent by Ernest Bevin to complete the work of the Nazis.

Of course it was a caricature, and wildly exaggerated. But the favorable Zionist and Israeli view of Abdullah had evaporated. Too much blood had been spilled.

In 1951, Abdullah went to his part of Jerusalem to pray. There, at the Aqsa mosque, he was assassinated by a Palestinian Arab conspirator. A British newsreel grandiloquently summarized his life:

In the capital of Amman, there is mourning in the palace and great sorrow in the hearts of the people. The king who made them a nation is no more. In the Great Arab Revolt, King Abdullah fought alongside Lawrence. He learned to love Britain, and in these days of trial, he was our friend. For this, he died. . . . A young fanatic killed the one man who might have brought peace to the Middle East.

On the last point, historians differ. Abdullah wasn’t that old, not even seventy, but he had aged badly. Could he have negotiated a peace agreement based on the status quo reached in the 1949 armistice? And would it have held? We can’t possibly know. We do know that, after his death and until 1967, the relations between Israel and Jordan were hostile, tense, and fraught with anticipation of another round. The de-facto partition didn’t last.

And here the parallel lives part ways. As I alluded at the start, Ben-Gurion still had more than a decade ahead as prime minister and defense minister. During that time, he built the ground floor of the state on the foundations laid before.

Still, there are a couple of final parallels. In the 1950s, Ben-Gurion’s Israel had to absorb hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees, mostly from Muslim countries: an influx that transformed it from a European Ashkenazi society into a multicultural one. In the same decade, Abdullah’s Jordan had to absorb hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arab refugees: an influx that fundamentally transformed it from a tribal society into a modern one. In both countries, postwar refugees became citizens. More: they and their descendants became the majority, a process that created huge stresses. In the course of that process, Israel proved a shining example of immigrant absorption, while Jordan did far better than other Arab countries in absorbing Palestinian refugees.

Perhaps this example of parallelism can be traced to Ben-Gurion and Abdullah’s analogous ideas of the nation. In Ben-Gurion’s view, Israel should welcome all Jews, from wherever they might come, as Israelis. In Abdullah’s view, Jordan should accept all Palestinians as Jordanians, since they were all Arabs.

Finally, although Ben-Gurion and Abdullah fought over Jerusalem and divided it between them, neither one is buried there. This is no coincidence: both were personally ambivalent about the city even as they would stop at nothing to ensure its inclusion in their respective states.

In his first two years after arriving in Palestine in 1906, Ben-Gurion didn’t visit Jerusalem even once. Only after returning to the country from a visit home to Płońsk did he set foot there. His indifference—or reluctance, or disdain—was common among many of his fellow ḥalutsim (pioneers). For them, Jerusalem was a city of the Old Yishuv—that is, of religious Jews who weren’t Zionist—and surly Arabs.

Only later, when the British made Jerusalem the capital of mandate Palestine and Zionists set up the Jewish Agency there, did Ben-Gurion spend much time in the city. Even so, in Jerusalem today there is no place associated with his legacy. His house, now a museum, is in Tel Aviv, and it was there, in the city’s art museum, that he declared Israel’s independence. When he retired from politics, he moved to a kibbutz, S’deh Boker, in the Negev, and decided he wanted to be buried there and not with other illustrious Zionist figures on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem.

But if, for Ben-Gurion, Israel’s future lay in the Negev, western Jerusalem was a place that, in the late 1940s, Israel had to possess. In order to fend off the persistent demand voiced by many world leaders and institutions, including the United Nations, that the city be internationalized, in 1949 he not only incorporated it into Israel but made it the nation’s capital—even though Tel Aviv would have been a more convenient choice. For Ben-Gurion, elevating Jerusalem had nothing to do with his own preferences or with any religious vision; after all, western Jerusalem did not include the sites holy to Judaism. It was a political and strategic necessity.

For Abdullah, though he died in Jerusalem by an assassin’s hand, the eastern part of that city had been the site of one of his greatest victories: the 1948 conquest by the Arab Legion of the Jewish Quarter, an operation that also secured for the Arabs the Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock. He was thus able to see himself as the savior of these holy places—despite the ingratitude of Arab Jerusalemites themselves, many of whom owed greater allegiance to his rival, the mufti, than to him.

Yet his funeral and burial took place in Amman, the village he had put on the map as a capital city. Like Tel Aviv, Amman was the new city, the creation of modern nationalism. There he truly belonged. Abdullah’s tomb in Amman is the center of a royal funerary complex, where his grandson, the late King Hussein, is also buried.

This prompts another question: after the 1948-49 war, why didn’t Abdullah, like Ben-Gurion, transfer the capital of his own state to eastern Jerusalem? In addition to matching Ben-Gurion’s move, such a transfer would have secured his grip in the city. Imagine for a moment that he had done so: would there have been a Six-Day War in June 1967? If there were such a conflict, would Israel have dared to occupy eastern Jerusalem, and then to annex it? Taking and keeping an Arab capital would have proved a far more difficult task, perhaps an impossible one.

Instead, however, Abdullah held back. His reasons were understandable: he didn’t trust the Arabs of Jerusalem. But this set the stage for the permanent loss of the city in 1967. In sharp contrast, Ben-Gurion’s action in 1949 set in motion the unification of the city and its de-facto acceptance as Israel’s capital. Yes, both men had reservations about Jerusalem, and neither is buried there. But Ben-Gurion built it up, while Abdullah and his successors played it down.

Of Ben-Gurion it may be said, as Germany’s Helmut Kohl once put it, that he was “one of the greatest leaders of our time.” It is a fair judgment: small as Israel is, its rebirth is one of the defining events of the 20th century.

Abdullah would not come close to deserving that title. Nevertheless, thanks in large part to him (and his descendants), Jordan represents one of the most successful instances of Arab state-building in the post-Ottoman Middle East. The elites of Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon looked down on him as, figuratively, an unreliable and grasping desert chieftain. But where are their countries today? When it comes to security and stability, most of the Arab world can’t hold a candle to Jordan, the country with which Israel is fortunate to share its longest border.

Jews everywhere must be thankful for David Ben-Gurion: history’s gift (in the phrase of the Zionist thinker Berl Katznelson) to the Jewish people. But they should never take for granted the Hashemites: history’s other, lesser gift to whom Israel owes much of its peace.

This essay originated as a lecture for the Tikvah Open University in August 2020.

More about: David Ben-Gurion, Israel & Zionism, Jordan, King Abdullah