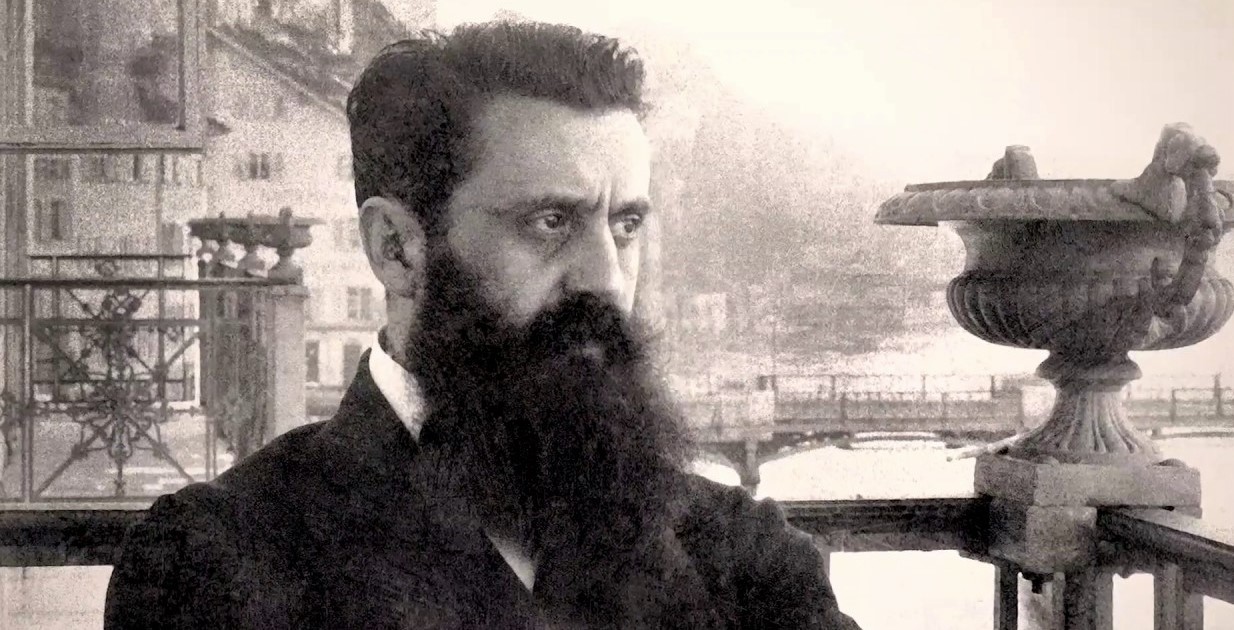

Theodor Herzl’s imprint on history grows stronger with every new day in the life of the Jewish people and the Jewish state. If there were still divinely inspired writers among us, they would compose the Book of Herzl on a biblical scale. Given our limitations, we simply track and integrate his legacy.

When I began reading and thinking about Zionism, back in my teens (when I imagined I was smarter than everyone else), I thought Herzl was ridiculous for having convened in 1897 the first Zionist Congress in Western Europe—in the concert hall of the Stadtcasino in Basel. Since the heartland of Zionism was obviously among the millions of Jews in tsarist Russia and Galicia, where Lovers of Zion organizations had already sprouted and established colonies in the Land of Israel, why force those young people to come to you rather than go to them? I wondered what kind of snobbery impelled this German speaker to choose a German-speaking venue?

Herzl’s idea as I saw it then was to make Zionism salonfähig, acceptable in high society, the justification being that the movement needed the respect of the Gentile leaders whose help he was seeking; that he wanted to impress the reporters who would hopefully cover this event. Maybe he hoped to show up the Jews of Munich who had prevented the gathering from being held in their city and make them envious of the glamor he was creating at Basel. As part of his effort to dignify the Congress, Herzl decreed that everyone come in formal dress, what my friends and I called “monkey suits,” in order to signify our inverted contempt for anyone who wore one. I thought all this had been pretentious and even dumb.

I was a snob of a different kind: a proud Lithuanian Jew, whose Jewishness was steeped in Yiddish. My culture admired dignified poverty, as a sign of which my mother’s delicacy always remained a slice of simple kimmel bread with schmaltz and garlic. So my heart went out to those students I read about like Chaim Weizmann who could not afford to attend the Congress and went collecting door to door for the money to send a representative of their group to Basel. These were the delegates that Herzl was asking to rent tuxedos?! And imagine my scorn on later learning this tidbit—that when Max Nordau, the second most prominent person on the program, dutifully turned up in a frock coat, Herzl asked him to change into white tie and tails, an even higher level of dress. White-tie Zionism—now there was a concept! No wonder the Jewish leftists accused Zionism of being a bourgeois indulgence. Why did Herzl care more about impressing the West than exemplifying the values of those who were actually reclaiming the Land of Israel?

I was dead wrong. Just how wrong I began to appreciate when I seriously took up the study of Yiddish literature and realized that had Herzl taken my advice—or the advice of other Jews from inside the Russian Pale of Settlement who thought like me—the project might not have materialized. Chaim Weizmann himself, future president of the state of Israel, but one of those students who couldn’t afford to get to the Congress, later concluded that Herzl’s influence, above all else that he accomplished, was due to the fact that “he came to us from a different world.” Weizmann wrote:

Studying his work, I have wondered if, had he known the Jews as we knew them, had he known Palestine as it really was at the time, he would have had the courage to do what he did. It was just because he came from a different environment that he attempted what others would not have dared to attempt.

Everything I learned about East European Jews supported Weizmann’s conclusion. Herzl needed the white tie and tails for the Jews of Berdichev, not Berlin. The formal attire was not meant to shame the East Europeans, God forbid, or to impress them with the customs of European society, or because he failed to understand the extra hardship it might impose on the penniless students. Had Herzl come from among those rabbinic students and shopkeepers, those Jews of Vilna and Buczacz who paid their shekel into the collection boxes, he could never have founded the political movement that stimulated and mobilized Jews to take their rightful place among the nations of the world.

Here’s how I came to understand this.

The first work I was assigned when I began my studies in Yiddish literature—the literature of the majority of Jews between 1860s and 1940—was a small novel called The Little Man, Dos kleyne mentshele, by the greatest genius of modern Jewish literature, Mendele Mokher Sforim, the “grandfather” of both modern Hebrew and modern Yiddish literatures. Written in the form of an ethical will, it tells the story of Isaac Abraham Takif—takif being a man of influence—who confesses how he learned to be a “little man” and what that term really means. Abused as a child, beaten by the teacher in his ḥeder, the Jewish school he attended, exploited in apprenticeship to a tailor and a cantor, Takif works his way up to become the factotum of Reb Isser Strangler (the names of the characters admit no subtlety in this morality tale), the richest man in town who teaches Takif how to fleece the community and financially to strangle its poor. He does this in hypocritical and cynical alliance with the religious authorities. The literary confession is a wholesale indictment of the Jewish community. It warns readers not to follow the leadership into becoming “little men”—morally diminished no matter how materially prosperous.

Sholem Aleichem followed in Mendele’s literary footsteps but with a gentler form of satire that made him the most beloved of all Yiddish writers. He created a gallery of “Little People with Small Ambitions,” kleyne mentshelekh mit kleyne hasoges, who were relatively harmless in a dangerous world. His town of diminutive Jews was called Kasrilevke, the shtetl of cheerful paupers.

To provide for the Sabbath—that is their goal in life. All week they labor and sweat, wear themselves out, live without food or drink, just so there is something for the Sabbath. And when the holy Sabbath arrives, . . . let Odessa be destroyed, let Paris itself sink into the earth! Kasrilevke lives! And since Kasrilevke was founded, no Jew has gone hungry there on the Sabbath. . . . If he has no fish, then he has meat. If he has no meat, then he has herring. If he has no herring, then he has bread, . . . and if not . . . then he borrows from his neighbor. Next week, the neighbor will borrow from him. “The world is a wheel and it keeps turning.”

You get the charm of this idea. These little people specialize in helping one another make do with little, making the most out of nothing.

In fact, part of this culture began to equate weakness with morality, as though suffering itself were proof of virtue. The great Yiddish writer and cultural figurehead I.L. Peretz wrote a striking story about Bontshe the Silent, a man so tame that he does not once complain about the abuse and injustice to which he is subject on earth and who, when he is then welcomed to heaven and offered anything he could wish for, asks for nothing more than a buttered roll. But what Peretz had written as a bitter satire of meek passivity the public took as a model of suffering sainthood, of righteous humility!

I could go on and on with such descriptions, written variously with affection or anger, criticism or concern, respect or disdain, in support of and protest against the way of life of these millions of Jews. And all this literary material is corroborated by the historians who estimate that at the end of the 19th century, 40 percent of Jewish males in the Russian Pale of Settlement were luftmenschen—a term they used to describe persons who lived on air, with no profession or steady source of income. Marc Chagall, who enjoyed making literal representations of Yiddish figures of speech, painted those Jews flying in the air, in der luftn, and when he wasn’t doing that, he was painting the Jew as Jesus on the cross, the sacrificed martyr. Chagall rendered his past very fondly, but the bright colors could not alter the vulnerability of the community they depict. True enough, without a state, Jews had developed strengths to compensate for their political dependency, but precisely because those were virtues of political dependency, they could not do the job of reclaiming political sovereignty.

I say this with no lack of appreciation. The strengths and virtues of these self-defined “little Jews” were indeed strengths and virtues. The many centuries of Jewish life in dispersion had created a mighty, resilient civilization. The Talmud’s counterintuitive teaching, “Who is a hero? He who conquers his urge,” produced men who did not have to brutalize their women and children, fight or kill to demonstrate their manhood, or destroy other civilizations to prove the greatness of theirs. These Jews championed heroism of the mind and spirit. That unheroic hero whom some would call “the little man” was the backbone of the same people whose traditions of self-reliance generated Israel’s start-up nation.

Furthermore, we know that centuries of adaptive wisdom had ginned up the beginnings of a national movement long before Herzl. Unlike the biblical Exodus that begins with God’s effort through Moses, the modern Zionist exodus story percolates from among the Jews who ceased being slaves millennia ago and had already begun priming for the homeward journey. “Hatikvah” was composed by Naftali Hertz Imber in the early 1880s and was one of several contenders to become the national hymn of the Jewish people. The settlement of Rishon LeZion, “First in Zion,” now the fourth largest city in Israel, was founded by a handful of Ukrainian Jews in 1882, fifteen years before the First Zionist Congress. Divine inspiration had long since become part of the lifeblood of the Jewish people—in Middle Eastern countries no less than in Eastern Europe—and once others began forging nation states, Jews began planning and making their way homeward. So these Jews did not need a Moses to release them from slavery: all they needed was the right political leader.

This is where Herzl became indispensable. For generations, biblical Jews didn’t want to be ruled by a king, but eventually they demanded that Samuel appoint one. The scattered and fiercely autonomous Jews of modernity didn’t want any leader either, but Herzl boldly seized the initiative. He was both Samuel the judge and Saul the king—he redefined the political situation of the Jews and then undertook to be their first sacrificial head. There were plenty of leaders among the Jews of Eastern Europe. Great religious personalities founded political and quasi-political movements; brilliant men and women established schools, publications, and cultural institutions. Political parties sprouted on the left with as many divisions—and generals—as the Russian army. But they could not have founded the Zionist movement because they experienced the Jewish condition from the inside, whereas Herzl saw how Jews figured in the world. All the other Jewish leaders located the “problem” and its solutions in the Jews themselves—as this people had been taught to do at Sinai and had been doing ever since. Herzl located the problem in the lack of political reciprocity between the Jews and other nations. The Jews could do anything they undertook to do, but until they were on an equal footing with other nations, none of it would matter. And an equal footing meant having a land underfoot.

Herzl was the correspondent of a major European newspaper, who covered politics on the continent and internationally. Others saw only part of the phenomenon, like the blind men in the parable, each of whom touches a different part of the elephant and extrapolates its nature from that. One touches the trunk and thinks it a snake, another thinks it a wall after bumping up against the side. Russian Jews said anti-Semitism lay in tsarist oppression. German Jews (of whom Herzl had been one) blamed it on Teutonic authoritarianism. But when Herzl moved to liberal France, he saw that the organization of politics against the Jews could become even more lethal in a democratic republic. Europe’s first politician to be elected on a platform of anti-Semitism was the mayor of its most cultured city, Vienna. So forget about adaptation as a strategy of Jewish survival. The more Jews adapted, the more they were despised. And forget the possibility of assimilation. The emerging nation states were not looking for mongrels. Jews had to establish political equality and gain peaceful coexistence, nation to nation. The only hope for them lay in Jewish political independence, within their own territory. But this was also the only hope for the world that was sliding into the hell of anti-Semitism. Jews had to establish this reciprocity quickly not only for their own sake but because anti-Semitism was the gift that kept on giving: gift being the German word for poison. Or virus.

Herzl told the Jews they were politically ready. There was nothing more to white-tie diplomacy than wearing its costume and assuming one’s rightful place in the family of nations. He showed them how to forge political autonomy, which included helping Jews everywhere, because addressing those hardships was part of the Jewish ethic of collective responsibility. This made the Jewish people big and worldly, not small and provincial. Jews did not have to wait to be admitted into the international fraternity—they had already proven themselves many times over. Herzl enunciated the Jewish claim on a world which had not yet risen to their level of mature behavior.

Herzl’s greatest asset was not merely that he came to us from a different world, as Weizmann put it, but that he was not a Jewish apologist. Had he been even slightly tinged by Marxism he would have bowed to the proletarian movement that was overtaking the youth of Europe. Even many of the youngsters valiantly moving to reclaim the Land of Israel called themselves Labor Zionists, to justify that their national impulse was tempered by the Marxist idea of progress. And on the other side of the Jewish divide, had Herzl been raised in certain branches of Jewish piety, he might still be apologizing to the Almighty for not yet having met His divine standards and promising to do better. Luckily for us, Herzl was a proud pragmatist when the moment called for political leadership, and although he could not part the Mediterranean Sea, he did everything he could to bridge the way.

We today celebrate the fulfillment of Herzl’s mission that far exceeded his dreams. The reality of Israel surpasses the most optimistic projections of Zionism. But the rest of the world failed to evolve in tandem with the Jews. Anti-liberal Arab leaders and Islamist imams, Communist and socialist ideologues, violators of human rights, resurfacing xenophobes of Europe, intersectional confederations of grievance and blame—there are more forces organized against Israel today than were aimed against the Jews a century ago. Thus, the task still before us corresponds exactly to what Herzl called for in Basel—reaffirming Jewish political sovereignty and ensuring that it remains unquestioned. Israel was, is, and will be the Jewish homeland and the world is much better for it.

Opposition to Israel on so many fronts has intimidated some among us. We have to shake up the faltering American Jews who are shrinking back into the little Jews of nebbishland and make them stand tall again, make them muster the political strength they failed to show in the 1930s.

We Americans have all the benefits of Herzl who stood at what was then the center of the political universe with the added advantage of citizenship in the land of the free. There is only one effective way Jews can help to repair the world—by ensuring unequivocal, unconditional, respect for the Jewish people in the Jewish state. Jewish statehood is not provisional, not conditional, and not required to justify or to prove itself to its enemies. Anti-Jews are everywhere and always the enemies of civilization and they must be opposed. America will only be as strong as its defense of its fellow democracies, and that begins with the Jewish state.

The work that Herzl heralded is ours to continue. Israel has begun the transformation of the Middle East. Our task is to see that 21st-century America does not return to the worst of 20th-century Europe. Please, for God’s sake and our own, let us reaffirm the nobility of the Jewish footprint in history.

The author was awarded the Tikvah Fund’s 2021 Herzl Prize, and this essay has been adapted from her acceptance speech, given on March 14 at the Jewish Leadership Conference.

More about: History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism