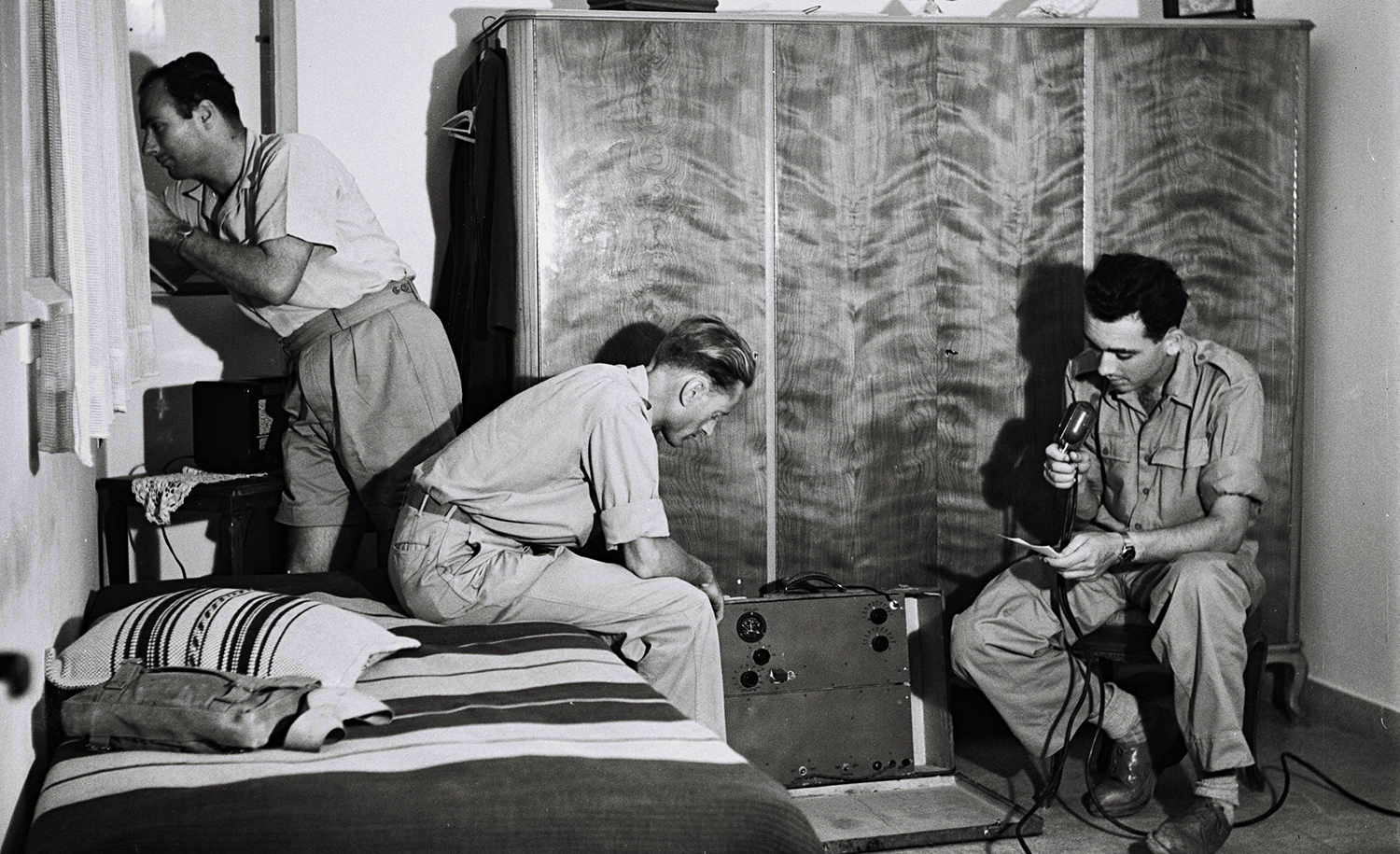

Jewish fighters at their radio in an undisclosed hideout on April 10, 1948, in the weeks before the founding of the state of Israel. Zoltan Kluger/GPO via Getty Images.

This is the second installment in the historian Martin Kramer’s series on how Israel’s declaration of independence came about, and what the text reveals about the country it brought into being. The previous essay can be seen here.—The Editors

Israel’s declaration of independence wasn’t something the founders had time to debate at leisure. It was compiled over a fairly brief period of time. The active interval was about three weeks long, from the third week of April 1948 right up to the hard deadline of May 14, the day prior to the date scheduled by the British for the end of the mandate and their departure from the land.

We owe a lasting debt to the Israeli legal scholar Yoram Shachar, who did the painstaking reconstruction of the declaration’s drafting process. Having tracked down the early versions, held in private hands, he pieced together the puzzle in an 80-page article in the Tel Aviv University Law Review (2002). His yeoman work was published before the papers themselves became a hot item when, in 2015, the heirs of the lawyer who composed the first drafts tried to sell them at auction at a starting price of $250,000. The state of Israel blocked the sale. In 2019, with arbitration having failed to resolve the issue, the Supreme Court ruled that the drafts were “part of the cultural property of the state of Israel, testament to our past, and part of our collective identity,” and were thus to be handed over to the state archives.

Three weeks

The drafting process itself was hugely complicated; what follows is a simplified outline that greatly compresses the process but will suffice for our larger purposes in this series of essays.

After various abortive starts and suggestions, the process really began on April 24, when Felix Rosenblueth (soon to be Pinḥas Rosen, the future first justice minister of Israel) asked Mordechai Beham, a thirty-three-year-old Tel Aviv lawyer, to try his hand at a draft. Beham went home and in turn asked help from a friend, Harry Solomon Davidovitch, a Lithuanian Jew who in the interim had served as a Conservative rabbi in America.

Davidovich had the text of the American Declaration of Independence. Copying parts of it by hand, Beham then translated it into Hebrew, making suitable emendations along the way, and submitted his draft to Rosenblueth. Dissatisfied with what he read, Rosenblueth gave it to his friend, the future Supreme Court justice Zvi Berenson, who would later claim to have written the declaration himself over a period of 48 hours without the aid of a preliminary text. The draft—clearly drawing upon Beham—then came back to Rosenblueth, who still wasn’t satisfied. So Beham and another jurist, Uri Yadin, took another stab at it.

At this point, May 12, the draft went to a five-man committee effectively headed by Moshe Shertok (later Sharett, Israel’s first foreign minister). Shertok worked through the night, at first from scratch but eventually making use of some of the previous draft. The next day, May 13, he presented his version to the committee, where it encountered disagreements. So David Ben-Gurion took the text home, closeted himself in his office, and in perhaps ten minutes reduced the declaration by a quarter and added crucial elements.

The next day, May 14, Ben-Gurion presented the draft as a fait accompli to the People’s Council, the yishuv’s proto-parliament, where a truncated debate took place. Promised by Ben-Gurion that they could make amendments later, the members adopted his version and rushed off to the Tel Aviv Museum where Ben-Gurion read the text before the nation and the world. Not a word has been changed since then.

Over the course of the three-week process, things had gone into and come out of the text in consonance with the preferences of individual drafters. Beham, the young lawyer working under the influence of a rabbi, entered the most religious elements. Berenson, a man of very liberal tendencies, made greater room for individual rights. Shertok and Ben-Gurion were concerned with establishing legitimacy.

Although the mix changed over time, all of these elements feature in the document as read on May 14. If the drafters had argued for another week, or a few days, or even a few hours, it would have read differently, just as it might have done had Ben-Gurion himself been as free to dwell on it as Thomas Jefferson was when working on the American Declaration of Independence.

But he wasn’t. While the declaration is identified with Ben-Gurion more than with anyone else, he didn’t spend much time on it. He believed there should be a declaration of statehood, but he let others do the drafting and didn’t devote much of any waking day to its content. In taking his final cut at it on the night before the declaration, he gave it his unique imprimatur but did so on the fly.

Ben-Gurion’s prime concern, though not his exclusive one, seems to have been to assure that the declaration said nothing that would limit Israel’s war plans. Thus, his diary entry for May 13, 1948, the day he edited the text, is almost entirely devoted to war matters. At that time (as we saw in last month’s essay), the Etzion Bloc, a cluster of Jewish settlements outside Jerusalem, was under siege by the Jordanian Arab Legion. In his diary, Ben-Gurion is clearly preoccupied with this emergency: lives are at stake, and so is the fate of Jerusalem itself. Only at the end of the entry does he laconically write: “At six o’clock, a People’s Council meeting to discuss the phrasing of the declaration which Moshe [Shertok] prepared. In the evening, I prepared the final edit of the draft”—namely, the draft he would offer to the People’s Council for its approval in the early afternoon of the next day.

When, at that meeting, objections were raised by attendees who were seeing the draft for the first time, and Ben-Gurion responded that they could express their reservations later but that for now they should accept it, this is how he explained it to them:

We are living in an abnormal time. First, the mandate ends today. Second, a state of emergency. Third, over the last few days we couldn’t bring in a significant number of [People’s Council] members stuck in Jerusalem, despite their legitimate request. . . . The purpose of the declaration isn’t to delve into political clarifications (and we have lots of political scores [to settle]). Its purpose: anchoring the declaration of independence. This is its main function. I agree . . . that the text isn’t the height of perfection. And there is no one among its drafters who thinks it’s the height of perfection. But the purpose was to give just those things that, in our opinion, provide a basis for what we’ll do today, for the people of Israel, world opinion, and the UN. We’re declaring independence, nothing more. This isn’t a constitution. As for the constitution, we will have a session on Sunday, when we will deal with it.

Having been asked to put their reservations aside, the members agreed to do so as a matter of urgent expediency. Had they had time for a general debate, certain passages might have read differently.

A friend of mine once told me he had read the declaration together with his granddaughter, dwelling on every phrase as though they were reading a portion of the Torah. Not only is there a natural inclination to do so, but there is a visual cue: the official copy of the declaration was written on parchment like a Torah scroll and in the same calligraphic font, Ktav Stam, used in preparing such a scroll. Indeed, the artifact in Hebrew is called a megillah, a “scroll,” a word also used to describe certain sacred writings.

Does it deserve the appellation? In the interest of adding perspective, it may be helpful to adduce a few rather mundane facts. For one thing, Ben-Gurion didn’t read the declaration from this scroll but from three mimeographed pages; precisely because the text had been in flux until the last minute, the calligrapher had no time to produce a final document for the ceremony. There, signatories affixed their signatures to a piece of blank parchment, temporarily attached to the mimeograph. That parchment was later stitched to two larger sections of, in the apt description of the Israel State Archives, “parchment-like paper” containing the calligraphic text, and then the “three parts were treated and made to look identical.” (In fact, while the parts do look identical, the stitches are clearly visible.) The complete object wasn’t ready until June.

The proper way to read the declaration, then, is to focus not only on the text but also on the stitches. These remind us of the degree to which this is a contingent text, evolving against a deadline in the midst of other dramatic developments and stitched together as phrases appeared and disappeared. Later, the text would be canonized, and its every nuance parsed as to the intent of the “founders.” Although no one can deny such intent, it is important to remember that any phrase may read “exactly” as it does because the drafters just ran out of time to debate it.

Here is one example, related to style rather than substance. One of the changes made by Ben-Gurion was in the way paragraphs opened. In the penultimate draft by Moshe Shertok, each paragraph began with “Whereas” (ho’il v’-): “Whereas the Jewish people,” “And whereas in every generation,” “And whereas the Mandate,” and so forth. There were nine of these, culminating with “Therefore” (l’fi-khakh) we declare the state.

The evening before the declaration, Ben-Gurion crossed out all of the “whereases.” Shertok never resigned himself to this alteration, as he explained in an interview thirteen years later:

I believe that [Ben-Gurion] weakened the logical sequence of the document. . . . I was of the opinion that by beginning the declaration with the word “whereas” and repeating it at the head of each paragraph, a sense of close continuity would be introduced which would keep the reader in growing suspense till the final hammer blow: “Therefore!”

Ben-Gurion did not believe that this kind of formulation was suitable for such a document, particularly in Hebrew, so he began his draft by simply citing a series of facts, one after the other. His conclusion, which also began with the word “Therefore,” had, to my mind, no apparent connection with what had preceded it. I thought that this constituted a serious defect in the declaration, but there was no time to thrash out the matter properly, so that is how it went.

Independence or statehood?

Another characteristic of the declaration, certainly as compared with the rousing language of the American Declaration of Independence, is its subdued tone. The difference is perhaps analogous to that between The Star-Spangled Banner and Hatikvah. The American national anthem is a call to rally around an embattled flag. The Israeli national anthem is about long-term perseverance, a hope that never flags. Whenever, at contemporary events, both anthems are played with a quick transition between them, the difference is palpable. Both are moving, but in very different ways, and this difference in tone can be traced to a very fundamental divergence between the two declarations themselves.

In particular, although the Israeli document is called a declaration of independence, its actual formal name is otherwise: the Proclamation of the State of Israel. Not independence, but statehood: the two may seem identical, but they are not.

Not every state has a declaration of independence. Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, for example, do not. Most states that do have declarations of independence had belonged to empires from which they separated or seceded, often in struggles of liberation. They thus declared independence from another polity; their declarations often include a long litany of complaints against the misrule of their former overlords, followed by a call to arms. Fully 70 percent of the American Declaration of Independence consists of a bill of particulars concerning King George III’s “repeated injuries and usurpations” and his trampling on the liberties of the colonists.

The yishuv likewise waged a struggle against the repeated injuries and usurpations of Britain under, in their case, King George VI. It was this Britain that shut the doors of the Jewish “national home” to the Jews of Europe at the hour of their greatest need—a greater injustice than any inflicted on the American colonies. Indeed, Britain’s decision to give up the Palestine mandate may have been partly the result of the blood-stained campaign waged against it by the Jewish underground in Palestine. Yet the Israeli declaration doesn’t include a single grievance against the departing imperial overlord.

Why not? There are two reasons.

First, a bill of particulars had already been delivered, and quite recently. This was the “Declaration of Political Independence” made by the Zionist Executive Council, the highest body of the Zionist Organization, on April 12—that is, a month before the end of the mandate. In a dramatic midnight session, the Council had declared “its decision to establish in the country the high authority of our political independence. . . . Immediately upon the end of the mandate, and no later than May 16, there will come into being a Jewish provisional government.” It was precisely to implement this decision that the Zionist Executive, in the same declaration, created the People’s Administration headed by Ben-Gurion.

The “Declaration of Political Independence” was written by Zalman Rubashov (later Shazar, the future third president of Israel), a man justly renowned for his rhetorical powers. Scholars don’t include it in the drafting history of the May 14 declaration because it can’t be shown that it was used as a source-text by the drafters. In my view, this underestimates its role as an inspiration. But, whatever its influence, the earlier declaration certainly exempted the later declaration from the need to settle open accounts with Britain. “Behold,” it cried,

the days of the British mandate have ended. On May 15, the UN will take back from the British government the trust given to it by the League of Nations 28 years ago, and which it did not uphold. The denial by the British mandate of its purpose grew and grew, and became in the last ten years the basis of Britain’s policy in the East. Instead of assisting the immigration of Jews to their national home, the gates were closed before the persecuted of our people in the most tragic hour of their dispersion. Britain imposed a blockade on those who reached these shores, and recruited forces from afar to condemn them to lives of danger and loss. They [the British] forfeited the barren lands of our country to the eternal desert and our dogged rivals; they chose as an ally the allies of the greatest tormentors of our people and the enemy of all humanity. The hand that locked the gates of the land in the face of our tortured brethren, for whose salvation the national home was mandated by the entire League of Nations, opened those same gates to the [Arab] vandals and invaders who entered through the crossings to prevent the implementation of the decision of the nations, and to plot to finish that which Satan [that is, Hitler] did not complete.

And now before Britain’s departure, the mandatory government strikes at the foundations of our creative work, and forfeits to chaos that which we built up with painstaking perseverance over generations. The land of our redemptive hope is about to become, God forbid, a trap for the remnant of Israel. Therefore, the world Zionist movement, in agreement with the entire house of Israel, is resolved, upon the end of the failed mandatory government, to banish foreign rule from the land of Israel, so that the people will rise up and establish its independence in its homeland.

Now, that sounds like a declaration of independence in the best American tradition. The British closed the gates of Palestine to the Jews? The British also closed the gates to the American colonies in order “to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; [and] refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither.” The British in Palestine allied themselves with our tormentors, opening the crossings to invaders? The British did the same to the American colonists by “endeavoring to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” And so on.

Thus, if none of this spirit made its way into the Israeli declaration, one reason is that Rubashov’s declaration already delivered the bill of indictment. But there is a second and more profound reason: the British didn’t have to be defeated and thrown out. That struggle had ended, and they were leaving. Nor was the Israeli declaration compelled to rally anyone against Perfidious Albion. The Jewish state, in the Israeli declaration, would arise as of May 15, 1948 in a void resulting from “the termination of the British mandate.” There would be no governing authority from which to declare independence.

The declaration doesn’t even declare the state now. In its words, the state just “comes into effect from the moment of the termination of the Mandate, being tonight”—not in opposition to or rebellion against anyone but as the successor to a vacated authority.

True, there had been one last stab at including a condemnation of the British. At the People’s Council meeting on the day of the declaration, Meir Vilner, of the Communist party, proposed an article denouncing the oppression of both Jews and Arabs by British colonialism. Shertok replied: “If we go into historical assessments and definitions, I’m afraid it will spoil the celebratory spirit of the declaration, and also its political logic at this time.” When another participant argued that Britain’s conduct since 1939 should at least be condemned by omitting any mention of the promises of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, Ben-Gurion ruled otherwise. “I disagree with the proposal to erase the Balfour Declaration. It’s ridiculous, and it would be understood as vindictive small-mindedness, and bad form.”

The new Jewish state also had something going for it that the American colonies lacked. States declaring independence from another polity usually have to build their legitimacy from scratch. Israel’s declaration assumes that the legitimacy of the state is a settled matter thanks to the UN General Assembly resolution of November 1947. It is the UN, says the Israeli declaration, that “passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel; the General Assembly required the inhabitants of Eretz-Israel to take such steps as were necessary on their part for the implementation of that resolution.” The yishuv, in establishing a state, was simply fulfilling a requirement of the international community.

In all of these respects, the circumstances of Israel’s birth were an anomaly, as was duly noted by Arthur Koestler in his 1949 book Promise and Fulfillment:

Virtually all sovereign states have come into being through some form of violent and, at the time, lawless upheaval which after a while became accepted as a fait accompli. Nowhere in history, whether in the time of the [post-Roman Empire] migrations, the Norman Conquest, the Dutch War of Independence, or the forcible colonization of America do we find an example of a state being peacefully born by international agreement. In this respect, Israel is a freak. It is a kind of Frankenstein creation, conceived on paper, blueprinted in the mandate, hatched out in the diplomatic laboratory.

Later, Koestler writes, at the implementation stage, Israel would secure its independence in a violent cataclysm, like all other states. But, like no other state in history, it received its license to exist by a two-thirds majority vote of the world’s other independent states. In declaring independence, moreover, Israel could claim to be on the side of international agreement, while the Arabs were in rebellion against it. So the declaration doesn’t include a call to arms; instead, it includes a call to Israel’s Arab neighbors for peace.

“Great modesty”

Because Israel never declared independence but merely statehood, some have complained that the declaration itself is anemic—a weak combination of self-justification and legalistic exposition. Drafted not by the nation’s writers or poets but by lawyers and politicians, it may legitimate the state but it hardly stirs its citizens to any kind of action.

This was one of the factors behind a contemporary expression of disappointment by Uri Yadin, one of the lawyers who had collaborated with Beham in working on the drafts. As he confided to his diary at the time:

It was a terrible disappointment for me; a deep depression descended upon me. The ceremony in the museum before a small audience, as though this was hidden. Without celebration, without an uplifting of the spirit, without inspiration of the historic hour. Such was the content of the declaration: watered-down, without strong emphases, confused, lacking all daring, decisiveness, or pride. What a distance between this speech-in-a-Zionist-committee and the ringing echoes of destiny we hoped would be sounded by the declaration.

Others have sounded a similar note from time to time. In response to such criticism, Elyakim Rubinstein, a former Supreme Court justice, has maintained that the declaration does indeed convey a “spirit of celebration.” But, whichever side one comes down on, there was and is a larger issue here.

America’s declaration is strident and bold because the resolve of American colonists needed to be stiffened. After all, they shared language and descent with their British overlords. They had once been loyal subjects of the same king, and now they were taking up arms against their brethren.

The Jews dwelled alone, and they knew it. They didn’t have to be told that they must fight, because they knew that if they didn’t, they would perish. No American colonist had anything like the Holocaust in the back of his mind.

What is more, the yishuv had been in a state of preparation for years. Arab attacks that had grown in intensity after November 1947; threats by Arab states to invade; the knowledge that Holocaust survivors, family, were still being turned away from Palestine’s shores—all of these meant that there was no need for a call to arms. In fact, the clandestine armies were already in place. All they needed now were real arms, which would begin to flow in with independence.

In this light, the declaration shared something of the character of the ceremony in which it was read out 73 years ago. This is how the journalist and Zionist functionary Yitzḥak Ziv-Av, who attended the proceedings, described them only a few days later:

The ceremony was very brief, slightly hurried, overly dry and without external markings of festivity. No features stimulating excitement or imagination. The ceremony began with the pounding of a gavel, and without words. With nothing more than a gesture of his hand Ben-Gurion invited us to stand for the singing of the anthem. While some might have expected to hear grand words—about fire, blood, shadows of the past, an end to subjugation, and an historical occasion—these words were not voiced. Everyone kept his emotions inside. One day we will appreciate the great modesty with which an embattled nation declared its state, its dream that had come true. Some perspective of time is needed for a person to understand that those 33 minutes changed him to the core—himself and every other Jew.

Indeed, the restraint in the document, as in the ceremony, was in some ways deceiving. Golda Meir, one of the two women signatories, described Shertok as “very controlled and calm as compared with me.” But, she would write in her memoirs,

he later told me that when he wrote his name on the scroll, he felt as though he were standing on a cliff with a gale blowing up all around him and nothing to hold on to except his determination not to be blown over into the raging sea below—but none of this showed at the time.

That is perhaps how best to appreciate the character both of the declaration and of the mood on that day in May: a lifeboat being outfitted in the midst of a brewing storm by a crew unbendingly determined to prevail even as the winds howl about them, water cascades over the deck, and shoals loom ahead.